Vittorio Storaro, ASC on Writing Poetry with Light

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rawrs Camera Wows

rawr21s camera wows British cameraman Ousama Rawi worked on the film Coup d'Etat in Toronto and shares with Mark Irwin some of his thoughts and techniques about lighting. by Mark Irwin Ousama Rawi checks a shot 22/ Cinema Canada / managed to meet Ousama Rawi two going to need a lot of light; it's going When Ossie Morris was shooting days before he began shooting Coup to be a very warm set. Equus here last year, he very openly d'Etat for Magnum Films. I had fol expressed his lack of confidence in lowed his work after seeing Pulp Canadian labs and their work. Have Your lighting style has managed to be (a Michael Caine comedy/thriller) you experienced any such horrors? a directional soft light. How have you in 1972. Since then I'd seen Black achieved that? Windmill, Gold and Sky Riders, all Well, Medallion is doing all our Some bounce, some diffuse. It de of them incredibly well photographed work. I spent a day with them and they pends on two factors: one, the location and I was very honored to finally meet were terrific. We're printing 5381 and we're shooting in, the height of the the man himself. not Gevaert because I think that final ceiling, the color of the ceiling, etc., ly 5247 and 5381 have now matured. I Born in Bagdad, and educated in and then two, the style of the director. was very disappointed when I first Scotland, he began shooting news for If he wants to pan through 270 degrees used 5247 before the modification Border Television in 1965. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

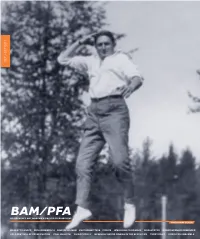

Berkeley Art Museum·Pacific Film Archive W in Ter 20 19

WINTER 2019–20 WINTER BERKELEY ART MUSEUM · PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PROGRAM GUIDE ROSIE LEE TOMPKINS RON NAGLE EDIE FAKE TAISO YOSHITOSHI GEOGRAPHIES OF CALIFORNIA AGNÈS VARDA FEDERICO FELLINI DAVID LYNCH ABBAS KIAROSTAMI J. HOBERMAN ROMANIAN CINEMA DOCUMENTARY VOICES OUT OF THE VAULT 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 CALENDAR DEC 11/WED 22/SUN 10/FRI 7:00 Full: Strange Connections P. 4 1:00 Christ Stopped at Eboli P. 21 6:30 Blue Velvet LYNCH P. 26 1/SUN 7:00 The King of Comedy 7:00 Full: Howl & Beat P. 4 Introduction & book signing by 25/WED 2:00 Guided Tour: Strange P. 5 J. Hoberman AFTERIMAGE P. 17 BAMPFA Closed 11/SAT 4:30 Five Dedicated to Ozu Lands of Promise and Peril: 11:30, 1:00 Great Cosmic Eyes Introduction by Donna Geographies of California opens P. 11 26/THU GALLERY + STUDIO P. 7 Honarpisheh KIAROSTAMI P. 16 12:00 Fanny and Alexander P. 21 1:30 The Tiger of Eschnapur P. 25 7:00 Amazing Grace P. 14 12/THU 7:00 Varda by Agnès VARDA P. 22 3:00 Guts ROUNDTABLE READING P. 7 7:00 River’s Edge 2/MON Introduction by J. Hoberman 3:45 The Indian Tomb P. 25 27/FRI 6:30 Art, Health, and Equity in the City AFTERIMAGE P. 17 6:00 Cléo from 5 to 7 VARDA P. 23 2:00 Tokyo Twilight P. 15 of Richmond ARTS + DESIGN P. 5 8:00 Eraserhead LYNCH P. 26 13/FRI 5:00 Amazing Grace P. -

ASC 100Th Reel 30-Second

E.T.: The Extra- John Seale, ASC, ACS Terrestrial (1982) Allen Daviau, ASC Enter the Dragon (1973) The Gold Rush (1925) Gil Hubbs, ASC Roland Totheroh, ASC The Godfather (1972) Citizen Kane (1941) Gordon Willis, ASC Gregg Toland, ASC ASC 100th Reel 30-Second The Tree of Life (2011) Apocalypse Now (1979) Clip Playlist Emmanuel Lubezki, ASC, Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC AMC The Dark Knight (2008) Link to Video here. Taxi Driver (1976) Wally Pfister, ASC Michael Chapman, ASC Close Encounters of the Kill Bill Vol. 1 (2003) Third Kind (1977) The Matrix (1999) Robert Richardson, ASC Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, Bill Pope, ASC HSC King Kong (1933) Jurassic Park (1993) Edward Linden; J.O. Blade Runner 2049 Dead Cundey, ASC Taylor, ASC; Vernon L. (2017) Walker, ASC Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC Braveheart (1995) John Toll, ASC Star Trek (1966) Gone With the Wind "Where No Man Has (1939) The French Connection Gone Before" Ernest Haller, ASC (1971) Ernest Haller, ASC Owen Roizman, ASC Sunrise (1927) Footloose (2011) Charles Rosher, ASC Game of Thrones (2017) Amy Vincent, ASC Karl Struss, ASC “Dragonstone” Gregory Middleton, ASC Sunset Boulevard (1950) Titanic (1998) John F. Seitz, ASC Russell Carpenter, ASC The Sound of Music (1965) Psycho (1960) The Graduate (1967) Ted D. McCord, ASC John L. Russell, ASC Robert Surtees, ASC The Wizard of Oz (1939) For more background Singin’ in the Rain (1952) Harold Rosson, ASC on the American Harold Rosson, ASC Society of Rocky (1976) Cinematographers, The Color Purple (1985) James Crabe, ASC go to theasc.com. Allen Daviau, ASC Frankenstein (1931) Empire of the Sun (1987) Arthur Edeson, ASC Allen Daviau, ASC Platoon (1986) Black Panther (2018) Robert Richardson, ASC Rachel Morrison, ASC Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) . -

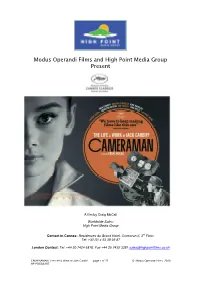

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present A film by Craig McCall Worldwide Sales: High Point Media Group Contact in Cannes: Residences du Grand Hotel, Cormoran II, 3 rd Floor: Tel: +33 (0) 4 93 38 05 87 London Contact: Tel: +44 20 7424 6870. Fax +44 20 7435 3281 [email protected] CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 1 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff www.jackcardiff.com Contents: - Film Synopsis p 3 - 10 Facts About Jack p 4 - Jack Cardiff Filmography p 5 - Quotes about Jack p 6 - Director’s Notes p 7 - Interviewee’s p 8 - Bio’s of Key Crew p10 - Director's Q&A p14 - Credits p 19 CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 2 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN : The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff A Documentary Feature Film Logline: Celebrating the remarkable nine decade career of legendary cinematographer, Jack Cardiff, who provided the canvas for classics like The Red Shoes and The African Queen . Short Synopsis: Jack Cardiff’s career spanned an incredible nine of moving picture’s first ten decades and his work behind the camera altered the look of films forever through his use of Technicolor photography. Craig McCall’s passionate film about the legendary cinematographer reveals a unique figure in British and international cinema. Long Synopsis: Cameraman illuminates a unique figure in British and international cinema, Jack Cardiff, a man whose life and career are inextricably interwoven with the history of cinema spanning nine decades of moving pictures' ten. -

BAM/PFA Program Guide Were Initiated by Bampfa.Berkeley.Edu/Signup

2011 SEP / OCT BAM/PFA UC BERKELEY ART MUSEum & PacIFIC FILM ARCHIVE PROGRAM GUIDE SILKE OTTO-KNAPp RICHARD MISRACh DESIRÉE HOLMAn KURT SCHWITTERs cREATe hIMALAYAN PILGRIMAGe DZIGA VERTOV RAINER WERNER FASSBINDER UCLA FESTIVAL OF PRESERVATIOn PAUL SHARITs yILMAZ GÜNEy nEW HOLLYWOOD CINEMA IN THE SEVENTIEs TERRY RILEY rOBIN COX ENSEMBLE 01 BAM/PFA EXHIBITIONS & FILM SERIES SILKE OTTO-KNAPP / MATRIX 239 P. 7 1991: THE OAKLAND-BERKELEY FIRE AfTErmATH PHOTOGRAPHS BY RICHARD MIsrACh P. 5 RICHARD MIsrACH: PHOTOGRAPHS from THE COLLECTIOn P. 6 DESIRÉE HoLMAN: HETEroTOPIAS / MATRIX 238 P. 9 CREATE P. 8 ROME, NAPLES, VENICE: MASTERWORKS from THE BAM/PFA COLLECTIOn P. 9 KURT SCHWITTErs: COLor AND COLLAGe P. 8 HIMALAYAN PILGRIMAGE: JOURNEY TO THE LAND of SNOWS P. 9 THom FAULDErs: BAMscAPE UCLA FESTIVAL of PrESErvATIOn P. 15 THE OUTSIDErs: NEW HoLLYWooD CINEMA IN THE SEVENTIES P. 12 SOUNDING Off: PorTRAITS of UNUSUAL MUSIC P. 18 ALTERNATIVE VISIONS P. 22 ANATOLIAN OUTLAW: YILMAZ GÜNEy P. 20 KINO-EYE: THE REvoLUTIONARY CINEMA of DZIGA VERTov P. 24 A THEATER NEAR You P. 19 PAUL SHARITS: AN OPEN CINEMa P. 23 HomE MovIE DAy P. 17 RAINER WERNER FAssbINDER: TWO GrEAT EPIcs P. 26 GET MORE Listen to artist Desirée Holman in conversation with curatorial assistant Dena Beard, bampfa.berkeley.edu/podcasts. Cover Dziga Vertov: Imitation of the "Leap from the Grotto" (PE 5), c. 1935; from the Vertov Collection, Austrian Film Museum, Vienna. Listen to the June 23 Create roundtable discussion, bampfa.berkeley.edu/podcasts. 01. Peter Bissegger: Reconstruction of Kurt Schwitters’s Merzbau, 1981-83 (original ca. 1930–37, destroyed 1943); 154 3/4 × 228 3/8 × 181 in.; Sprengel Museum Hannover; Photo: Michael Herling/ Learn more about L@TE artists and programmers at bampfa.berkeley.edu/late. -

Production Designer Jack Fisk to Be the Focus of a Fifteen-Film ‘See It Big!’ Retrospective

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRODUCTION DESIGNER JACK FISK TO BE THE FOCUS OF A FIFTEEN-FILM ‘SEE IT BIG!’ RETROSPECTIVE Series will include Fisk’s collaborations with Terrence Malick, Brian De Palma, Paul Thomas Anderson, and more March 11–April 1, 2016 at Museum of the Moving Image Astoria, Queens, New York, March 1, 2016—Since the early 1970s, Jack Fisk has been a secret weapon for some of America’s most celebrated auteurs, having served as production designer (and earlier, as art director) on all of Terrence Malick’s films, and with memorable collaborations with David Lynch, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Brian De Palma. Nominated for a second Academy Award for The Revenant, and with the release of Malick’s new film Knight of Cups, Museum of the Moving Image will celebrate the artistry of Jack Fisk, master of the immersive 360-degree set, with a fifteen-film retrospective. The screening series See It Big! Jack Fisk runs March 11 through April 1, 2016, and includes all of Fisk’s films with the directors mentioned above: all of Malick’s features, Lynch’s Mulholland Drive and The Straight Story, De Palma’s Carrie and Phantom of the Paradise, and Anderson’s There Will Be Blood. The Museum will also show early B- movie fantasias Messiah of Evil and Darktown Strutters, Stanley Donen’s arch- affectionate retro musical Movie Movie, and Fisk’s directorial debut, Raggedy Man (starring Sissy Spacek, Fisk’s partner since they met on the set of Badlands in 1973). Most titles will be shown in 35mm. See below for schedule and descriptions. -

Introduction

CINEMATOGRAPHY Mailing List the first 5 years Introduction This book consists of edited conversations between DP’s, Gaffer’s, their crew and equipment suppliers. As such it doesn’t have the same structure as a “normal” film reference book. Our aim is to promote the free exchange of ideas among fellow professionals, the cinematographer, their camera crew, manufacturer's, rental houses and related businesses. Kodak, Arri, Aaton, Panavision, Otto Nemenz, Clairmont, Optex, VFG, Schneider, Tiffen, Fuji, Panasonic, Thomson, K5600, BandPro, Lighttools, Cooke, Plus8, SLF, Atlab and Fujinon are among the companies represented. As we have grown, we have added lists for HD, AC's, Lighting, Post etc. expanding on the original professional cinematography list started in 1996. We started with one list and 70 members in 1996, we now have, In addition to the original list aimed soley at professional cameramen, lists for assistant cameramen, docco’s, indies, video and basic cinematography. These have memberships varying from around 1,200 to over 2,500 each. These pages cover the period November 1996 to November 2001. Join us and help expand the shared knowledge:- www.cinematography.net CML – The first 5 Years…………………………. Page 1 CINEMATOGRAPHY Mailing List the first 5 years Page 2 CINEMATOGRAPHY Mailing List the first 5 years Introduction................................................................ 1 Shooting at 25FPS in a 60Hz Environment.............. 7 Shooting at 30 FPS................................................... 17 3D Moving Stills...................................................... -

5. Bibliografía

5. BIBLIOGRAFÍA AGUADERO FERNÁNDEZ, Francisco. Diccionario de comunicación audiovisual. Madrid: Paraninfo, 1991. ALBERS, Josef. Interaction of color. La interacción del color. Madrid: Alianza, 1980, (1963). ALBRECHT, Donald. Designing dreams. Modern architecture in the movies. EE.UU.: Thames and Hudson, 1986. ALEKAN, Henri. Des lumieres et des ombres. París: F. Editions, 1980. Reeditado en París. Librairie du Collectioneur, 1991. ALMENDROS, Néstor. Días de una cámara. 2a. ed. Barcelona: Seix Barral. 1983, (1990). (Titulo original: Un homme á la caméra.1ª edición en francés. Renens- Lausanne: Forma,1980). ALPERS, Svetlana. El Arte de Describir. El arte holandés en el siglo XVII. Madrid: Hermann Blume, 1987. ALTON, John. Painting with light. Nueva York: The Macmillan Company, 1950. ARAGON, y otros autores. La Photographie Ancienne. Lyon: Le Point revue artistique et littéraire. (posterior a) 1942 ARGAN, Giulio Carlo. El arte moderno 1770-1970. Valencia: Fernando Torres, 1977. AUER, Michel. The illustrated history of the camera. Hertfordshire, Reino Unido: Fountain Press, 1975. AYMA, Pierre; MARTINS FERREIRA, Armando; LYONS, Robin; ROUXEL, Jacques. The european animation industry's production handbook. Glossary and multilingual lexicon. Bruselas, Bélgica: Cartoon, 1992. BAUDRY, Marie-Thérèse y otros. Principes d’analyse scientifique. LA SCULPTURE. Méthode et vocabulaire. París: Imprimerie Nationale, 1990 (1978, 1984). BALTRUSAITIS, Jurgis. EL ESPEJO ensayo sobre una leyenda científica Madrid: miraguano, polifemo, 1988. Before Hollywood. “Turn-of-the-century film from american archives”. Nueva York: American Federation of Arts, 1986. [Publicación que acompaña la exhibición de la se- lección de filmes de “Before Hollywood”]. BERG, W. F. Exposure. Theory and practice. Londres: Focal Press, 1971, (1950). BERGMANS, J. La visión de los colores. -

• ASC Archival Photos

ASC Archival Photos – All Captions Draft 8/31/2018 Affair in Trinidad - R. Hayworth (1952).jpg The film noir crime drama Affair in Trinidad (1952) — directed by Vincent Sherman and photographed by Joseph B. Walker, ASC — stars Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford and was promoted as a re-teaming of the stars of the prior hit Gilda (1946). Considered a “comeback” effort following Hayworth’s difficult marriage to Prince Aly Khan, Trinidad was the star's first picture in four years and Columbia Pictures wanted one of their finest cinematographers to shoot it. Here, Walker (on right, wearing fedora) and his crew set a shot on Hayworth over Ford’s shoulder. Dick Tracy – W. Beatty (1990).jpg Directed by and starring Warren Beatty, Dick Tracy (1990) was a faithful ode to the timeless detective comic strip. To that end, Beatty and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC — seen here setting a shot during production — rendered the film almost entirely in reds, yellows and blues to replicate the look of the comic. Storaro earned an Oscar nomination for his efforts. The two filmmakers had previously collaborated on the period drama Reds and later on the political comedy Bullworth. Cries and Whispers - L. Ullman (1974).jpg Swedish cinematographer Sven Nykvist, ASC operates the camera while executing a dolly shot on actress Liv Ullman, capturing an iconic moment in Cries and Whispers (1974), directed by friend and frequent collaborator Ingmar Bergman. “Motion picture photography doesn't have to look absolutely realistic,” Nykvist told American Cinematographer. “It can be beautiful and realistic at the same time. -

Storms Named After People

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2018 Storms Named After People Sarah E. Ballard University of Central Florida Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Ballard, Sarah E., "Storms Named After People" (2018). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 338. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/338 STORMS NAMED AFTER PEOPLE by SARAH BALLARD A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Film Production in the College of Arts and Humanities and in the Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term, 2018 Thesis Chair: Elizabeth Danker, M.F.A, M.A. ABSTRACT Storms Named After People is a coming-of-age film about loneliness, Florida’s disposition during holidays, freedom within abandonment, and how one translates time and space when alone. I intend for this film to capture a unique and authentic representation of young women that I find difficult to come by in mainstream cinema. Some other things I plan to accomplish with Storms Named After people include subverting the audience’s expectations, challenging tired stereotypes of women and various relationships among them, capturing loneliness from an optimistic point of view and embracing availability within a micro-budget filmmaking process. -

British Society of Cinematographers

Best Cinematography in a Theatrical Feature Film 2020 Erik Messerschmidt ASC Mank (2020) Sean Bobbitt BSC Judas and the Black Messiah (2021) Joshua James Richards Nomadland (2020) Alwin Kuchler BSC The Mauritanian (2021) Dariusz Wolski ASC News of the World (2020) 2019 Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC 1917 (2019) Rodrigo Prieto ASC AMC The Irishman (2019) Lawrence Sher ASC Joker (2019) Jarin Blaschke The Lighthouse (2019) Robert Richardson ASC Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood (2019) 2018 Alfonso Cuarón Roma (2018) Linus Sandgren ASC FSF First Man (2018) Lukasz Zal PSC Cold War(2018) Robbie Ryan BSC ISC The Favourite (2018) Seamus McGarvey ASC BSC Bad Times at the El Royale (2018) 2017 Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC Blade Runner 2049 (2017) Ben Davis BSC Three Billboards outside of Ebbing, Missouri (2017) Bruno Delbonnel ASC AFC Darkest Hour (2017) Dan Laustsen DFF The Shape of Water (2017) 2016 Seamus McGarvey ASC BSC Nocturnal Animals (2016) Bradford Young ASC Arrival (2016) Linus Sandgren FSF La La Land (2016) Greig Frasier ASC ACS Lion (2016) James Laxton Moonlight (2016) 2015 Ed Lachman ASC Carol (2015) Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC Sicario (2015) Emmanuel Lubezki ASC AMC The Revenant (2015) Janusz Kaminski Bridge of Spies (2015) John Seale ASC ACS Mad Max : Fury Road (2015) 2014 Dick Pope BSC Mr. Turner (2014) Rob Hardy BSC Ex Machina (2014) Emmanuel Lubezki AMC ASC Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014) Robert Yeoman ASC The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) Lukasz Zal PSC & Ida (2013) Ryszard Lenczewski PSC 2013 Phedon Papamichael ASC