Transcript of Interview Conducted May 25 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Giving America Back the Blues

GIVING AMERICA BACK THE BLUES OVERVIEW ESSENTIAL QUESTION How did the early Rolling Stones help popularize the Blues? OVERVIEW The Rolling Stones ultimately made their mark as the nonconformist outlaws of Rock and Roll. But before they were bad boys, the Stones were missionaries of the Blues. The young Rolling Stones — Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Brian Jones, Charlie Watts, and Bill Wyman — were white kids who hailed from working- and middle-class Britain and set out to play American music, primarily that of African Americans with roots in the South. In so doing, they helped bring this music to a new, largely white audience, both in Britain and the United States. The young men who formed the Rolling Stones emerged from the club scene fostered by British Blues pioneers Cyril Davies and Alexis Korner. These two men and their band, Blues Incorporated, helped popularize the American Blues, whose raw intensity resonated with a generation of Britons who had grown up in the shadow of war, death, the Blitz, postwar rationing, and the hardening of the Cold War standoff. Much of the Stones’ early work consisted of faithful covers of American Blues artists that Davies, Korner, and the Stones venerated: Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Slim Harpo, Jimmy Reed. The early Stones in particular helped make the Blues wildly popular among young Britons. As the Stones’ fame grew and they became part of the mid-1960s British “invasion” of America, they also reintroduced the Blues to American listeners, most notably young, white audiences with limited exposure to the music. But almost from day one, the Stones were more than a Blues cover band. -

The Charter Quay Site, Kingston, Documentary Research Report

THE CHARTER QUAY SITE, KINGSTON, DOCUMENTARY RESEARCH REPORT Dr Christopher Phillpotts, BA, MA, PhD, AIFA The Saxon period The topography of Kingston in the Saxon period consisted of low islands of gravel capped with brickearth, standing proud of the alluvial marshland of the Thames floodplain. The central Kingston island lay between the course of the Thames to the west, two branches of the River Hogsmill to the south and east, and the Downhall/Latchmere Channel to the north. Trench 3 of the site lay on the western edge of this island at the confluence of the Thames and the southern branch of the Hogsmill. To the south lay a series of smaller gravel islands running parallel with the course of the Thames. Trenches 1 and 2 of the site lie on the north- west part of the northernmost of these islands, adjacent to the Hogsmill (Hawkins 1996, 4.2; Hawkins 1998, 271-2). The evidence of recent excavations suggests that early Saxon settlement in the area was concentrated on the island to the south of the Hogsmill. Occupation evidence of the sixth and seventh centuries was found here at South Lane, including at least one substantial hall building. Other activities were taking place on the higher ground to the east of the central Kingston island, although these may have been of an agricultural character. The central island was probably unoccupied at this period (Hawkins 1998, 273, 275-6, 278). By the eighth century the focus of settlement had shifted to the central Kingston island. The excavated evidence of the late Saxon period here is characterised by ditches dug into the brickearth to drain the low-lying island and mark out property boundaries (Hawkins 1996, 5.3.4, 5.3.5; Hawkins 1998, 276-8). -

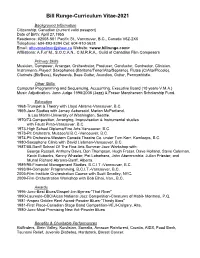

Bill Runge-CV2021

Bill Runge-Curriculum Vitae-2021 Background Information Citizenship: Canadian (current valid passport) Date of Birth: April 27,1955 Residence: #2508-501 Pacific St., Vancouver, B.C., Canada V6Z-2X6 Telephone: 604-893-8394 Cel: 604-910-5638 Email: [email protected] Website: <www.billrunge.com> Affiliations: A.F.of M., S.O.C.A.N., C.M.R.R.A., Guild of Canadian Film Composers Primary Skills Musician, Composer, Arranger, Orchestrator, Producer, Conductor, Contractor, Clinician. Instruments Played: Saxophones (Baritone/Tenor/Alto/Soprano), Flutes (C/Alto/Piccolo), Clarinets (Bb/Bass), Keyboards, Bass Guitar, Acordion, Guitar, Pennywhistle. Other Skills Computer Programming and Sequencing, Accounting, Executive Board (10 years-V.M.A.) Music Adjudication- Juno Judge 1998/2008 (Jazz) & Fraser Macpherson Scholarship Fund. Education 1968-Trumpet & Theory with Lloyd Abrams-Vancouver, B.C. 1969-Jazz Studies with Jamey Aebersold, Marion McPartland, & Lou Marini-University of Washington, Seattle. 1970/73-Composition, Arranging, Improvisation & Instrumental studies with Faust Pinto-Vancouver, B.C. 1973-High School Diploma/Fine Arts-Vancouver, B.C. 1973-Pit Orchestra, Mussoc/U.B.C.-Vancouver, B.C. 1974-Pit Orchestra-Western Canada Theatre Co. under Tom Kerr, Kamloops, B.C. 1980-Saxophone Clinic with David Liebman-Vancouver, B.C. 1987/88-Banff School Of The Fine Arts Summer Jazz Workshop with: George Russell, Anthony Davis, Don Thompson, Hugh Fraser, Dave Holland, Steve Coleman, Kevin Eubanks, Kenny Wheeler, Pat Labarbera, John Abercrombie, Julian Priester, and Muhal Richard Abrams-Banff, Alberta. 1989/90-Financial Management Studies, B.C.I.T.-Vancouver, B.C. 1993/94-Computer Programming, B.C.I.T.-Vancouver, B.C. -

Brian Auger´S Oblivion Express Feat. Alex Ligertwood

Brian Auger´s Oblivion Express feat. Alex Ligertwood Alex Ligertwood (li.) und Brian Auger (re.) „Brian Auger (* 18. Juli 1939 in London) ist einer der profiliertesten Jazz- und Rock-Keyboarder der Gegenwart. Für seine Millionen Fans ist der einzigartige Sound, der seine Wurzeln im Jazz, Rock, Soul und Funk hat, ein unverkennbares Markenzeichen des berühmten Hammond - und Keyboard -Spielers. Schon früh erhielt Auger Klavierunterricht. 1962 formierte er sein Brian Auger Trio mit Rick Laird und Schlagzeuger Phil Kinorra als zunächst reine Jazzcombo. 1965 gründete er zusammen mit Rod Stewart, Julie Driscoll und John Baldry die Gruppe The Steampacket. Nachdem Rod Stewart und John Baldry die Gruppe verlassen hatten, gründete Auger mit Julie Driscoll die Gruppe Trinity. In dieser Besetzung hatte die Band mehrere Single-Hits (Road ToCairo, This Wheel's on Fire, Season Of The Witch) und brachte das viel beachtete Doppelalbum „Streetnoise“ (1969) heraus. Nachdem Driscoll 1969 Trinity verließ, besetzte Auger die Gruppe um (mit Gary Boyle), doch konnte er nicht mehr an die Erfolge der späten 1960er Jahre anknüpfen und löste Trinity 1970 auf. Auch mit seiner anschließend gegründeten Band Oblivion Express hatte Auger zunächst keinen übermäßigen Erfolg. Seit dem Album „CloserToIt“ (1973), das es in die Charts schaffte, festigte sich der Gruppenstil zu einer groove-betonten Mischung aus rhythmischen Elementen des R&B und Funk und harmonischen und melodischen Elementen des Jazz. Brian Auger trat auch mit Klaus Doldinger, Alexis Korner, Pete York, Eric Burdon und anderen Größen der populären Musik auf. 1974 zog Auger in die USA, wo er weiter Alben aufnahm. In den USA bekam er wieder Kontakt zu Julie Tippetts-Driscoll. -

The Anchor Public House, Bankside, London Borough of Southwark

The Anchor Public House, Bankside, London Borough of Southwark An Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment for The Spirit Group by Steve Preston Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code ABS07/86 July 2007 Summary Site name: The Anchor Public House, Bankside, London Borough of Southwark Grid reference: TQ3244 8040 Site activity: Desk-based assessment Project manager: Steve Ford Site supervisor: Steve Preston Site code: ABS07/86 Area of site: c. 850 sq m Summary of results: The site is in an area of considerable archaeological potential and is occupied by a listed building. Previous evaluation trenching on the site exposed elements of 17th-century building (made ground layers, a cobbled surface and a cess pit) and later (18th- to 20th-century) works interpreted as possibly part of a waterworks, but nothing from any earlier period. This report may be copied for bona fide research or planning purposes without the explicit permission of the copyright holder Report edited/checked by: Steve Ford9 31.07.07 Jennifer Lowe9 02.08.07 i Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd, 47–49 De Beauvoir Road, Reading RG1 5NR Tel. (0118) 926 0552; Fax (0118) 926 0553; email [email protected]; website : www.tvas.co.uk The Anchor Public House, Bankside, London Borough of Southwark An Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment by Steve Preston Report 07/86 Introduction This desk-based study is an assessment of the archaeological potential of approximately 850 sq m of land located on Bankside in Southwark (TQ 3244 8040) (Fig. 1). The project was commissioned by Mr Mark Thackeray of Cliff Walsingham and Company, Bourne House, Cores End Road, Bourne End, Buckinghamshire SL8 5AR on behalf of The Spirit Group, and comprises the first stage of a process to determine the presence/absence, extent, character, quality and date of any archaeological remains which may be affected by redevelopment of the area. -

John, Sir Elton (B.1947) by Nathan G

John, Sir Elton (b.1947) by Nathan G. Tipton Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Sir Elton John on stage in 2008. Photograph by Elton John has, over five decades, achieved an amazingly successful track record in Richard Mushet. the music industry. He was not only the biggest-selling pop superstar of the 1970s, Image appears under the but, more surprisingly, he continues to retain popularity among his fans and respect Creative Commons from music critics. Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license. Elton John holds a music industry record for most consecutive singles placed in the Top 40, a string that began in 1970 and was broken only in 2000. Stephen Erlewine has noted that, although Elton John has endured temporary slumps in creativity and sales, he continues to craft contemporary pop standards that showcase his musical versatility. John's combination of melodic skills, dynamic charisma, and raucous performance style has made him a remarkably popular musical artist. Elton John was born Reginald Kenneth Dwight in Pinner, Middlesex, England on March 25, 1947. Dwight began playing piano at age four and, when he was eleven, won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music in London. After six years at school, he left in order to break into the music business. In 1961 he joined his first band, Bluesology, but left in 1966 because of creative differences with bandleader Long John Baldry. During this time Dwight had answered a Liberty Records advertisement for songwriters; and, though he failed the vocal audition, he was given a stack of lyrics written by Bernie Taupin, a young songwriter from Lincolnshire who had also answered the ad. -

Read an Extract

1964 FIRED by his live experiences with The Konrads and searching for an escape from his ad agency job, David resolves to make a go of music with George Underwood. David is the focal point on vocals and saxophone when they form The King Bees with three older musicians, playing hard-edged R&B. A cheeky appeal for financial backing to magnate John Bloom results in contact with agent/manager Leslie Conn, who also handles another unknown, Marc Bolan. Conn signs a deal with Decca for a single, ‘Liza Jane’, with ‘Louie, Louie Go Home’ on the B-side. David leaves his day job and becomes a fully fledged professional musician. Promotion for the single includes an appearance on Ready Steady Go! and BBC TV’s The Beat Room, with David also playing saxophone. The failure of ‘Liza Jane’ to chart leads to the disbandment of The King Bees. Conn has already hooked David up with The Manish Boys from Kent, though tensions arise over billing and David finds himself shuttling between Bromley and their base in Maidstone. Davie Jones & The Manish Boys play R&B venues all over south-east England but struggle to make an impact. David makes his first appearance at Soho club the Marquee, which will become a significant venue in his life. He also meets girlfriend Dana Gillespie there. In an attempt to create a stir, David forms The Society ANY DAY NOW l DAVID BOWIE l THE LONDON YEARS NOW l DAVID ANY DAY For The Prevention Of Cruelty To Long-Haired Men, again appearing on national TV. -

Brian Auger & the Trinity & Julie Driscoll

a division of BRIAN AUGER & THE TRINITY & JULIE DRISCOLL “The Mod Years” Elisabeth Richter Hildesheimer Straße 83 30169 Hannover GERMANY Tel.: 0049‐511‐806916‐16 Fax: 0049‐511‐806916‐29 Cell: 0049‐177‐7218403 elisabeth.richter@mig‐music.de www.mig‐music.de Release: 24.06.2010 CD Kat. Nr.: MIG 00492 Format: 1 CD Jewel Genre: Rock Brian Auger talks about “The Mod Years” It was in April-May 1965, when Long John Baldry saw me playing in the Manchester club “The Twisted Wheel”. Baldry was already a famous name at that time. He even had his own hour a division of on television, so big deal. I was called to a meeting the following week with John, his manager and agent. John’s Hoochie Coochie Men were breaking up. It was suggested that my trio, the Trinity with bassist Rickey Brown and drummer Mickey Waller would become the rhythm section of the new band. I added Vic Briggs, John wanted his protégé Rod Stewart to sing with us. I suggested adding singer Julie Driscoll, who at that time was working in my manager’s office but waiting to start a career with a band. The Steampacket were a tremendous success live and went on to be called the first Supergroup. I arranged and interpreted stuff for everybody in the band. Because of arguments as what label to record for, we missed recording our own album. After the breakup, Baldry changed the band into The Shotgun Express and The Brotherhood, with Elton John at the piano. This anthology compiles tunes from before 1966. -

Refugees of the French Revolution: Émigrés in London, 1789–1802

Refugees of the French Revolution Émigrés in London, 1789–1802 Kirsty Carpenter REFUGEES OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION This page intentionally left blank Refugees of the French Revolution Émigrés in London, 1789–1802 Kirsty Carpenter First published in Great Britain 1999 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0–333–71833–X First published in the United States of America 1999 by ST. MARTIN’S PRESS, INC., Scholarly and Reference Division, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 ISBN 0–312–22170–3 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Carpenter, Kirsty, 1962– Refugees of the French Revolution : émigrés in London, 1789–1802 / Kirsty Carpenter. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0–312–22170–3 1. French—England—London—History—18th century. 2. France– –History—Revolution, 1789–1799—Refugees. 3. French—England– –London—History—19th century. 4. Political refugees—England– –London—History. I. Title. DA676.9.F74C37 1999 942'.00441—dc21 99–13682 CIP © Kirsty Carpenter 1999 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. -

Edition 0172

Est 2016 London Borough of Richmond upon Thames 0172 Contents TwickerTape TwickerSeal History Through Postcards Arts and Entertainment Council Tax Increase Twickenham Riverside Climate Change SWR Compensation Twickers Foodie WIZ Tales Borough View The Mayflower Theatre Reviews Football Focus Eel Pie Island Contributors TwickerSeal Alan Winter Emma Grey TwickWatch Sammi MacQueen Alison Jee Graeme Stoten St Mary’s Bruce Lyons Mark Aspen James Dowden RFU LBRuT Editors Berkley Driscoll Teresa Read High water mark, March 17th 1774, Twickenham Riverside (2.25m above road level) Photo by Berkley Driscoll TickerTape - News in Brief Rugby At Twickenham Station ENGLAND v IRELAND Sunday 23rd February, Kick off 1500. Expected attendance 82,000 Full CPZ in operation We expect Whitton, Rugby & London Roads to be closed between 1300 and 1500, and 1640 - 1900. Bus shuttles run from Hounslow and Old Deer Park, which residents may use for free. Free exhibition space for young local artists at Art House Open Studios Richmond Art House Open Studio Festival is offering young visual artists, designers and makers from across the borough the opportunity to take part in the 2020 Open Studios Festival for free, as part of its new First Steps Programme initiative. The annual festival, which celebrates visual arts in the borough, takes place over the final two weekends in June, Friday 19 to Sunday 21 and Friday 26 to Sunday 28 June. More information and online applications to take part in Art House Open Studio 2020. The deadline for artist applications is Saturday 29 February. Toadblock… beware! Residents in Church Road in Ham are being asked to keep their eyes open for breeding toads which are shortly due to commence their annual carriageway cross. -

River Thames- Hampton Court to Richmond Moderate Trail: Please Be Aware That the Grading of This Trail Was Set According to Normal Water Levels and Conditions

River Thames- Hampton Court to Richmond Moderate Trail: Please be aware that the grading of this trail was set according to normal water levels and conditions. Weather and water level/conditions can change the nature of trail within a short space of time so please ensure you check both of these before heading out. Route Summary Distance: 7 miles This section of the River Thames has much of interest en- Approximate Time: 2-3 Hours route with activity on the water, the mixed landscapes of The time has been estimated based on you travelling 3 – 5mph parkland and town, and historic landmarks. The trail is (a leisurely pace using a recreational type of boat). suitable for all abilities by either canoe or kayak in normal Type of Trail: One Way river conditions. Waterways Travelled: River Thames For ease of parking and launching the trail commences at Type of Water: River urban West Molesey, approximately ¾ mile upstream of Hampton Court Bridge. Portages and Locks: 2 locks Nearest Town: Richmond The reaches between Molesey and Richmond are some of Start: - Hurst Park, West Molesey, London, KT8 1ST MR the busiest on the river with canoes, rowers, sailing 176/134691 dinghies, motor cruisers, hire boats and passenger launch services, especially at weekends. Do keep an eye on Finish: River Lane, Petersham, Richmond Mr 176 other river traffic and comply with navigation rules 178735, TW10 7AG Start Directions O.S. Sheets: Landranger No. 176 – West London Licence Information: A licence is required to paddle this waterway. See full details in Useful Information Hurst Park, West Molesey, London, KT8 1ST MR below. -

Download It As A

Richmond History JOURNAL OF THE RICHMOND LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY Numbers 1–39 (1981–2018): Contents, Author Index and Subject Index This listing combines, and makes available online, two publications previously available in print form – Journal Numbers 1 to X: Contents and Index, republished with corrections in October 2006, and Journal Numbers XI to XXV: Contents and Index, published in November 2004. This combined version has been extended to cover all issues of Richmond History up to No. 39 (2018) and it also now includes an author index. Journal numbers are in Arabic numerals and are shown in bold. Although we have taken care to check the accuracy of the index we are aware that there may be some inaccuracies, inconsistencies or omissions. We would welcome any corrections or additions – please email them to [email protected] List of Contents There were two issues in 1981, Richmond History's first year of publication. Since then it has been published annually. No. 1: 1981 The Richmond ‘Riverside Lands’ in the 17th Century James Green Vincent Van Gogh in Richmond and Petersham Stephen Pasmore The development of the top of Richmond Hill John Cloake Hesba Stretton (1832–1911), Novelist of Ham Common Silvia Greenwood Richmond Schools in the 18th and 19th centuries Bernard J. Bull No. 2: 1981 The Hoflands at Richmond Phyllis Bell The existing remains of Richmond Palace John Cloake The eccentric Vicar of Kew, the Revd Caleb Colton, 1780–1832 G. E. Cassidy Miscellania: (a) John Evelyn in 1678 (b) Wordsworth’s The Choir of Richmond Hill, 1820 Augustin Heckel and Richmond Hill Stephen Pasmore The topography of Heckel’s ‘View of Richmond Hill Highgate, 1744’ John Cloake Richmond in the 17th century – the Friars area James Green No.