The Charter Quay Site, Kingston, Documentary Research Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 Crystal Palace – Brixton – Trafalgar Square

3 CrystalPalace–Brixton–TrafalgarSquare 3 Mondays to Fridays CrystalPalaceBusStation 0555 0747 0847 1543 1859 1909 1919 1931 1943 1955 CroxtedRoadParkHallRoad 0603 Then 0758 Then 0900 Then 1552 Then 1907 1917 1927 1939 1951 2003 HerneHillStationDulwichRoad 0611 about 0809 about 0913 about 1601 about 1915 1925 1935 1947 1959 2010 BrixtonStation 0619 every7-8 0821 every8-9 0924 every8 1611 every8-9 1924 1934 1944 1956 2008 2018 KenningtonChurch(forOvalStation) 0627 minutes 0831 minutes 0934 minutes 1621 minutes 1934 1944 1954 2006 2017 2027 MillbankLambethBridge 0637 until 0850 until 0945 until 1632 until 1943 1953 2003 2015 2026 2036 TrafalgarSquareCockspurStreet 0644 0901 0957 1644 1952 2002 2010 2022 2033 2043 CrystalPalaceBusStation 2007 2131 2143 2155 2207 2219 2231 2243 2255 2310 2325 2340 2355 CroxtedRoadParkHallRoad 2014 Then 2138 2150 2202 2213 2225 2237 2249 2301 2316 2331 2346 0001 HerneHillStationDulwichRoad 2021 every12 2145 2157 2208 2219 2231 2243 2255 2307 2322 2337 2352 0007 BrixtonStation 2028 minutes 2152 2204 2214 2225 2237 2249 2301 2313 2328 2343 2358 0013 KenningtonChurch(forOvalStation) 2037 until 2201 2212 2222 2233 2245 2257 2307 2319 2334 2349 0004 0019 MillbankLambethBridge 2046 2210 2221 2231 2242 2254 2306 2316 2328 2343 2358 0013 0028 TrafalgarSquareCockspurStreet 2053 2217 2228 2238 2249 2301 2313 2323 2335 2350 0005 0020 0035 3 Saturdays (also Good Friday) CrystalPalaceBusStation 0555 0610 0625 0640 0655 0710 0725 0740 0752 0804 0814 0824 0832 0840 0848 0855 0902 0910 CroxtedRoadParkHallRoad 0602 0617 0632 -

Download Network

Milton Keynes, London Birmingham and the North Victoria Watford Junction London Brentford Waterloo Syon Lane Windsor & Shepherd’s Bush Eton Riverside Isleworth Hounslow Kew Bridge Kensington (Olympia) Datchet Heathrow Chiswick Vauxhall Airport Virginia Water Sunnymeads Egham Barnes Bridge Queenstown Wraysbury Road Longcross Sunningdale Whitton TwickenhamSt. MargaretsRichmondNorth Sheen BarnesPutneyWandsworthTown Clapham Junction Staines Ashford Feltham Mortlake Wimbledon Martins Heron Strawberry Earlsfield Ascot Hill Croydon Tramlink Raynes Park Bracknell Winnersh Triangle Wokingham SheppertonUpper HallifordSunbury Kempton HamptonPark Fulwell Teddington Hampton KingstonWick Norbiton New Oxford, Birmingham Winnersh and the North Hampton Court Malden Thames Ditton Berrylands Chertsey Surbiton Malden Motspur Reading to Gatwick Airport Chessington Earley Bagshot Esher TolworthManor Park Hersham Crowthorne Addlestone Walton-on- Bath, Bristol, South Wales Reading Thames North and the West Country Camberley Hinchley Worcester Beckenham Oldfield Park Wood Park Junction South Wales, Keynsham Trowbridge Byfleet & Bradford- Westbury Brookwood Birmingham Bath Spaon-Avon Newbury Sandhurst New Haw Weybridge Stoneleigh and the North Reading West Frimley Elmers End Claygate Farnborough Chessington Ewell West Byfleet South New Bristol Mortimer Blackwater West Woking West East Addington Temple Meads Bramley (Main) Oxshott Croydon Croydon Frome Epsom Taunton, Farnborough North Exeter and the Warminster Worplesdon West Country Bristol Airport Bruton Templecombe -

Abbess Close, Tulse Hill, London, SW2 £360,000 Leasehold

Abbess Close, Tulse Hill, London, SW2 £360,000 Leasehold Purpose built apartment Modern family bathroom suite Two double bedrooms Large living and entertaining area Neutral decor Separate W/C Bright and spacious throughout Private balcony Contemporary fitted kitchen Parking available 2, Lansdowne Road, Croydon, London, CR9 2ER Tel: 0330 043 0002 Email: [email protected] Web: www.truuli.co.uk Abbess Close, Tulse Hill, London, SW2 £360,000 Leasehold **Vendor Comments** "We really love this flat. The neighbourhood is quiet, despite being near so many amenities. Since we bought it five years ago we’ve put in a new kitchen & bathroom; painted & wallpapered all the walls and carpeted & tiled every floor. We left here to get married and brought our baby home here. We hosted our parents for Christmas dinner and had sun-downers on the balcony in the summer. The location is ideal, near Tulse Hill, Herne Hill and West Norwood stations. We’re 20 minutes from central London via Tulse Hill station or 35 minutes via bus and Brixton tube station. We get to park outside our flat permitting and cost free too, which is a plus. We know and talk to all our neighbours in our small block and 3 years ago the residents association was setup. There’s also a community hall for hire which is very nearby where we hosted our baby's christening party. We’re a 5 minute walk from Brockwell park with its picnic spots, lido, miniature railway and park runs. There’s the Tulse Hill Hotel for lunch or a drink and two breweries next to the park (Bullfinch & Canopy). -

Mortlake House Chiswick High Road, London W4 5RH

Mortlake House Chiswick High Road, London W4 5RH Welcome to Mortlake House Chiswick High Road, London This beautifully presented and stylish apartment located in the heart of Chiswick offers spacious, contemporary accommodation spanning over 740 Sq Feet. The property comprises three double bedrooms, a stunning reception room, a modern family bathroom and a well-equipped integrated kitchen. Mortlake House is superbly placed only 500m from Gunnersbury Station (District Line and Overground), a short walk to Chiswick Business Park, with the fabulous selection of boutiques and restaurants on Chiswick High Road just beyond, as well as further access to the M4 route to the west. Please call Barnard Marcus now on 020 8994 5432 for more information or to book a viewing. Welcome to Mortlake House Chiswick High Road, London Three double bedroom apartment on the third floor of a purpose built building Living accommodation of approx. 742sq ft. internally Stunning reception room with big bright windows allowing a natural flow of light throughout Stylish kitchen and bathroom Located within the heart of Chiswick, along the High Road Tenure: Leasehold EPC Rating: D £500,000 Please note the marker reflects the view this property online barnardmarcus.co.uk/Property/BEP105957 postcode not the actual property see all our properties on zoopla.co.uk | rightmove.co.uk | barnardmarcus.co.uk Lease details are currently being compiled. For further information please contact the branch. Please note additional fees could be incurred for items such as leasehold packs. 1. MONEY LAUNDERING REGULATIONS Intending purchasers will be asked to produce identification documentation at a later stage and we would ask for your co-operation in order that there is no delay in agreeing the sale. -

Brand New 19,000 Sq Ft Grade a Office

BRAND NEW 19,000 SQ FT GRADE A OFFICE 330 CLAPHAM ROAD•SW9 If I were you... I wouldn’t settle for anything less than brand new Let me introduce you to LUMA. 19,000 sq ft of brand new premium office space conveniently located just a short stroll from Stockwell and Clapham North underground stations. If I were you, I know what I would do... 330 Clapham Road SW9 LUMA • New 19,000 sq ft Office HQ LUMA • New 330 Clapham Road SW9 LUMA • New 19,000 sq ft Office HQ LUMA • New I’d like to see my business in a new light Up to 19,000 sq ft of Grade A office accommodation is available from lower ground to the 5th floor, benefiting from excellent views and full height glazing. 02 03 A D R O N D E E A M I L 5 1 Holborn 1 A E D G W £80 per sq ft A R E R O A City of London D Soho A 1 3 C O M M E Poplar R C I A L R City O A D D £80 per sq ft A O White City R A 1 2 0 3 T H E H I G H W A Y Mayfair E Midtown G D Hyde I R Park B £80 per sq ft R E W O T 0 0 A 3 Holland 1 3 A 2 0 Park St James Waterloo Park Southwark D £71 per sq ft A O R L £80 per sq ft L E W M O R Westminster C E S T A 4 W O A D per sq ft W E S T C R O M W E L L R £75 Vauxhall Belgravia £55 per sq ft D V 330 Clapham Road SW9 A R U Isle of Dogs Pimlico X K H R A L A L P B R N I A D O 2 G E T N G E W N I C auxa R D N O R O A S O R N S S V E N E R R O K O G A 2 1 2 D A 3 3 A B Oa A A 2 T 0 Oval T 3 LUMA • New 19,000 sq ft Office HQ LUMA • New Battersea E R S S Battersea E L £50 per sq ft A Park £50 per sq ft A M A Fulham B 2 R B 0 D D E 2 I A D O T A C G R H A K O M E R R A R B P E D R A R N W D E Peckham R S E E T O L A T L B T 5 N E 2 0 X W R O 3 I A D A R B D per Camberwell I’d want my business A 3 O £45 sq ft 2 R A A tocwe 3 andswort S located in Central London’s 2 R 2 A oad 0 D E Louborou E most cost effective C L unction S 6 P 1 E 2 T R 3 A L U C Capam R I H C H T A U O S 5 R i t. -

Visiting Artists

Welcome Pack VISITING ARTISTS Hello! Streatham Space Project is a new live performance venue, purpose-built for Streatham and Greater London. The venue includes a 123 seat fully-flexible auditorium for theatre, music, comedy, dance and family friendly activities; a rehearsal room for dance classes, yoga, theatre workshops as well as plenty more; and a buzzing café and bar area. Streatham Space Project is an experiment in what an arts space can do for a neighbourhood like Streatham and the wider London community. Enclosed you will find information about Streatham Space Project including travel, contact and access information. We look forward to welcoming you soon! X The SSP Team CONTACT INFO Executive Director Lucy Knight – [email protected] Venue and Operations Manager Lexie McDougall – [email protected] Marketing Ella Kilford – [email protected] Production Manager [email protected] 1 GETTING HERE Address: Streatham Space Project Sternhold Avenue London, SW2 4PA TRANSPORT Tube/Bus The nearest tube stations are Brixton, Balham and Tooting Bec. The nearest bus stop is Streatham Hill/Streatham Hill Station. From Brixton busses 109, 118, 133, 159, 250 and 333 run towards Streatham Hill Station From Tooting Bec bus route 319 runs towards Streatham Hill Station From Balham bus route 255 runs towards Streatham Hill Station Rail Streatham Hill Station is a 1-minute walk from Streatham Space Project and runs towards London Bridge and Victoria Streatham Station is 15-minute walk to Streatham Space Project along Streatham High Road Bike There are bike racks along Streatham High Road, there is currently no bike parking at Streatham Space Station and bikes should not be brought into the building Car Parking Streatham Space Project has no parking spaces available on site. -

Annual Report 2007 2008

1946 Mind Annual Report 6/10/08 11:15 Page 1 Richmond Borough Mind Annual Report 1946 Mind Annual Report 6/10/08 11:15 Page 2 April 2007-March 2008 Achievements and Performance This has been another year of change, as the Recovery Approach was Carers Support & Training introduced throughout the statutory mental health services in Richmond, We welcome the new Carers Strategy 2007-2010, a challenge to us all in Richmond Borough Mind to adapt to new, more whose aims include improved well being and quality of life for carers; making sure their contribution is outward looking, positive and empowering ways of working. recognised; increasing choice, control and information and providing training for carers and professionals. We continued to shape our service so it has a key role in In line with our strategic aims, we sought to modernise As an organisation, we have become stronger in the realising these aims: investigating the use of Carers and diversify our services throughout the year, tailoring course of the year, securing income for more frequent Vouchers, increasing the resources of our information activities at our drop-ins to attract a wide spectrum of in-house support and training for our staff, and library; and making funding bids for well being sessions. service users and fundraising for resources to move into working to strengthen our infrastructure in order to new fields like TimeBanking, Befriending and work to employ a Finance Officer and an Administrative The three support groups continued to meet in support Peer-Support groups. Later in the year, we Assistant as well as volunteers. -

Low Cost/No Cost Family Fun in London Please Look at Organisations’ Websites to Double Check Times and Arrangements

Low Cost/No Cost Family Fun in London Please look at organisations’ websites to double check times and arrangements London Open House weekend 22 and 23 September – locations across London Open House London is the world’s largest architectural festival, giving FREE public access to 800+ buildings, walks, talks and tours over one weekend in September each year. To find out what’s happening visit: www.openhouselondon.org.uk Examples include: Kia Oval (Surrey Cricket Ground), SE11 5SS Saturday 21 September 10am – 5pm. The Edible Bus Stop Studio, Arch 511, Ridgway Road, SW9 7EX Sunday 22 September 2 – 6pm A former mechanics garage, refurbished, utilising reclaimed and recycled materials to create a design studio and workshop. Brixton Windmill, Blenheim Gardens, Brixton Hill SW2 5EU 21 and 22 September 1 – 4.30pm The only surviving windmill in inner London, built in 1816. Guided tours of the exterior and first two floors, bookable through the website. Please note that the flors beyond the first floor are accessed by steep ladder-stairs, children must be over 1.2m in height. Lambeth Tower Hall 21 and 22 September - 10am – 5pm Warwick & Austin Hall Landmark Edwardian Baroque style town hall in red brick and Portland stone. striking new atrium, reception and courtyard space along with grand marble lined staircase and ornate council chamber. Grade 2 listed. National Theatre, Upper Ground, South Bank, SE1 9PX 21 September 10am -5pm and 22 September 12.15-5pm Housing one of the world’s most important producing theatres! The building is a key work in British Modernism with three theatres, designed with workshops and theatre-making all on site. -

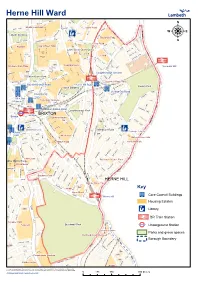

Herne Hill Ward AY VEW RO C B G O D R U OA M PS R O TA R N L D D L T S a YN T OST N O

Herne Hill Ward AY VEW RO C b G O D R U OA M PS R O TA R N L D D L T S A YN T OST N O M R S A T M T E L R M A PL E A W R R L N O Myatts Field South R S O K O OAD RT A T Paulet Road T E R R U C B A D E P N N N R T E LO C L A C R L L E D T D R A T S R U R E K E R B I L O E B N E H PE A L NFO U A L C R D M W D A S D T T A P A Y N A R A W Slade Gardens R O N V E C O E A K R K D L A D P H C L Thorlands TMO A RO R AD B UGH ORD O EET RO LILF ROA U TR HBO D R S G K RT OU E SA L M B T N C O M R S D I A B A A N L U L O E SPICE E Lilford Road D R R R D R : T E A Y E T D O C R CLOSE E A R R N O O Angell Town TMO Sch R S A S T M C A Robsart Y L O T E A E A I V D R L N D R W E C F A R O E R E O L V T A I L R T O F L N D A Elam Street Open Space D N E L R V E R AC O A PL O FERREY O R B D H A U O R N A S U D TO MEWS G A I AY T Sch N D L O D A H I C WYNNE T D L K Hertford E B A W N O W O E E V R L I N RD SERENADERS Lilford R GR L O A R N A Y E P N O T A MEWS E M N A O R S A E U O W D S S U K S W R M T I S O C N T R G E A G K L X B O T L R A H E W K ROAD R A P U A K R O D R O E S L A DN O U D D G F R O O A D B R V L A Sch U A U X G Loughborough O H H D R R A Stockwell Park TMO AN D D N A GE F S L O Denmark Hill L E T L S R A R O T T E Y E L L T C H RK R E E A A O Y S R OAD L P A B VILLA R EL S D R G O G N M D D U N E M R Sch A RD A N D R A E G L R S D W L L R A O Y S L SE M A Loughborough Junction UM B S E R E F T D D N Y N W E R C F E R C O I S A H D E E I A L R M T C C D D T S U W B Max Roach Park R R R I O G N A P D A I D F G S T 'S O D A N N H E S -

An Exceptional 19Th Century Family Home with Coach House And

TERMS Approximate Gross Internal Area = 4,701 sq ft / 436.7 sq m Coach House = 842 sq ft / 78.3 sq m Borough: London Borough MORTLAKE HOUSE Total = 5,543 sq ft / 515 sq m of Richmond upon Thames LONDON SW14 Total Size of Site = 0.49 Acres EPC E Second Floor Coach House First Floor First Floor Coach House Ground Floor Ground Floor Viewing: Strictly by appointment with Savills. Savills East Sheen Important notice 298a Upper Richmond Savills, their clients and any joint agents give notice that: 1: They are not authorised to make or give any representations or warranties in relation to the property either here or Road West, elsewhere, either on their own behalf or on behalf of their client or otherwise. They assume no responsibility for any statement that may be made in these particulars. These London SW14 7JG particulars do not form part of any offer or contract and must not be relied upon as statements or representations of fact. 2: Any areas, measurements or distances are [email protected] An exceptional 19th century family home with Coach House approximate. The text, photographs and plans are for guidance only and are not necessarily comprehensive. It should not be assumed that the property has all necessary 020 8018 7777 planning, building regulation or other consents and Savills have not tested any services, equipment or facilities. Purchasers must satisfy themselves by inspection or otherwise. and gardens of just under half an acre. 18/12/XX XX 362629 savills.co.uk MORTLAKE HOUSE The excellent facilities offered by East Sheen are approximately a third of a mile away; the historic town of Richmond is within a short drive featuring LONDON SW14 charming paved courtyards and lanes with an eclectic selection of boutiques and bars complementing most of the well-known high street retailers on George Street. -

1000 Years of Barnes History V5

Over 1000 years of Barnes History Timeline from 925 to 2015 925 Barnes, formerly part of the Manor of Mortlake owned by the Archbishop of Canterbury, is given by King Athelstan to the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral. 1085 Grain sufficient to make 3 weeks supply of bread and beer for the Cathedral’s live-in Canons must be sent from Barnes to St Paul’s annually. Commuted to money payment late 15th Century. 1086 Domesday Book records Barnes valued for taxation at £7 p.a. Estimated population 50-60. 1100 - 1150 Original St Mary‘s Parish Church built at this time (Archaeological Survey 1978/9). 1181 Ralph, Dean of St Paul’s, visits Barnes, Wednesday 28th Jan to assess the value of the church and manor. The priest has 10 acres of Glebe Land and a tenth of the hay crop. 1215 Richard de Northampton, Priest at the Parish Church. Archbishop Stephen Langton said to have re-consecrated the newly enlarged church on his return journey from Runnymede after the sealing of Magna Carta. 1222 An assessment of the Manor of Barnes by Robert the Dean. Villagers must work 3 days a week on the demesne (aka the Barn Elms estate) and give eggs, chickens and grain as in 1085 in return for strips of land in the open fields. Estimated population 120. 1388 Living of Barnes becomes a Rectory. Rector John Lynn entitled to Great Tithes (10% of all produce) and right of fishing in Barnes Pond. 1415 William de Millebourne dies at Milbourne House. -

Lambeth's Creative & Digital Industries Strategy for Growth

Creative ways to grow. Lambeth’s Creative & Digital Industries Strategy for Growth Contents Foreword 3 Our vision 4 Our strategy 7 Building on our strengths 19 Meeting the challenges 31 Making it happen 56 Working in partnership 69 ActionSpace Lambeth’s Creative & Digital Industries Strategy for Growth 1 Foreword For the first time the council has taken a look at the current performance and future potential of Lambeth as a creative and digital hub. Our strategy identifies the opportunities and threats; the benefits of growth for our our residents, businesses and places; and how we can encourage and support this dynamic sector. It is the result of truly co-productive work. Over many months we have brought together creative and digital businesses, education providers, trade bodies, young residents, thought leaders and social entrepreneurs. We have explored individual and collective ambitions. We have recognised the challenges and how we might achieve success. Now we have the foundation and commitment to make Lambeth the next destination and, in time, leader for London’s creative and digital economy. Lambeth Council has a pivotal role to play in growing the sector. It has a unique opportunity. We welcome, encourage and work in partnership with businesses and we expect that collaboration to benefit our community. Lambeth has all the right elements to build thriving and sustainable creative and digital clusters. Our strategy is a clear commitment to achieve this aim. It fits within the borough’s Strategic Plan, Future Lambeth, which draws on Lambeth’s strengths, potential and values to transform its goals into reality.