Issues of Identity Among the Valmikis and Ravidasis in Britain: Egalitarian Hermeneutics from the Guru Granth Sahib

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viral Research & Diagnostic Laboratories (VRDL), Department

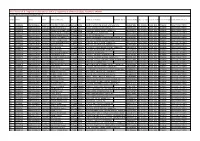

Viral Research & Diagnostic Laboratories (VRDL), Department of Microbiology, KCGMCH, KARNAL COVID Reports are available at kcgmc.edu.in Sr. No LAB ID SRF ID UHID NAME OF PATIENT AGE SEX ADDRESS OF PATIENT QUARANTINE AT CONTACT NUMBERDATE OF SAMPLEDATE RECEIVING OF REPORTINGPLACE OF SAMPLINGCOVID REPORT STATUS 1 KC402656 606700328611 1322711 RAVINDER MANDHAN (India)33 Years Male NEAR EX SARPANCH HOUSE, SAMALKHA Pin: 8168497900 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 2 KC402658 606700328624 1153128 JASBIR SINGH (India) 35 Years Male H NO 8, ANAND COLONY, KARNAL Pin: 7988762425 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 3 KC402659 606700328113 1190289 SAJJAN CHAUDHARY (India)26 Years Male KR HOUSE, MEERUT ROAD, KARNAL Pin: 9416008555 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 4 KC402660 606700328629 1322722 DEEPAK ROHILLA (India) 35 Years Male H NO 598, SEC 4 ,KARNAL Pin: 9253751923 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 5 KC402661 606700328639 1195592 RAKESH KUMAR (India) 40 Years Male 23, SEC 32, KARNAL Pin: 9812050003 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 6 KC402662 606700328635 1322723 SHIV RAJ ACHARIYA (India)30 Years Male SASTRI NAGAR,NEAR MATA MANDIR, KARNAL Pin: 8375959950 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 7 KC402663 606700328651 1322724 BHARAT SINGH (India) 53 Years Male CENTURY PLYWOOD, GANGER RAMBA ROAD, TARAORI9996712825 KARNAL Pin: 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 8 KC402666 606700328678 1322727 SATYA NARAYAN (India) 75 Years Male H NO 201, MODEL TOWN, KARNAL Pin: 9215534567 -

Containment Zones

As on 4-June Containment Zones as identified by Ward level MOHs & Teams | @MyBMC | For updates, pl visit http://StopCoronavirusMCGMGovIn/insights-on-map *This is a revised list post rationlisation and reorganisation of earlier CZs for better utilisation of manpower and more effective containement Kindly refer the notes mentioned on the website Also, reach out to your respective Ward's teams in case of any discrepency for them to help update Ward # Pincode Address A 1 400001 M.R.A. Police Quarters,M.R.A. Road,Fort A 2 400001 M.R.A. Bmc Colony,M.R.A. Road,Fort A 3 400001 Ramgad Vasahat Zopadpatti,P D'Mello Road,Near St George Hospital,Fort A 4 400001 Servant Quarters, Cama Hospital,Mahapalika Marg,Fort A 5 400005 Sunder Nagari,Azad Nagari, Darya Nagar,Lala Nigam Road, Near Colaba Market,Sunder Nagar,Colaba A 6 400005 Machchimar Nagar,Capt. Prakash Pethe Marg,Colaba A 7 400005 Ganeshmurti Nagar Part No.1,2,3,Captain Prakash Pethe Marg,Ganeshmurthi Nagar,Colaba A 8 400005 Shivshakti Nagar, Garib Janata Nagar, Mahatma Phule Nagar,Capt. Prakash Pethe Marg,Colaba A 9 400005 Ambedkar Nagar,Capt. Prakash Pethe Marg,Colaba A 10 400005 Geeta Nagar,Dr Homi Bhabha Road,Near Navy Nagar,Colaba A 11 400005 Narayan Chawl 13, First Koli Lane,Rajwadkar Street,Colaba A 12 400005 7 Kashinath House, 5Th Koli Lane,Lala Nigam Road,Colaba A 13 400005 Meherzin Building,Sbs Road,Colaba B 14 400003 Cement Chawl No. 1,Madhavrao Rokade Road,Masjid Bunder Railway Station,Mandvi B 15 400003 Chatal Chawl,Sant Tukaram Road,Ahmadabad Street,Masjid Bunder B 16 400003 Hutment,1St Clive Road,Near Ashok Hotel,Masjid Bunder B 17 400003 Cement Chawl No. -

Redalyc.Visiting a Hindu Temple: a Description of a Subjective

Ciencia Ergo Sum ISSN: 1405-0269 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México México Gil-García, J. Ramón; Vasavada, Triparna S. Visiting a Hindu Temple: A Description of a Subjective Experience and Some Preliminary Interpretations Ciencia Ergo Sum, vol. 13, núm. 1, marzo-junio, 2006, pp. 81-89 Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México Toluca, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=10413110 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Visiting a Hindu Temple: A Description of a Subjective Experience and Some Preliminary Interpretations J. Ramón Gil-García* y Triparna S. Vasavada** Recepción: 14 de julio de 2005 Aceptación: 8 de septiembre de 2005 * Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy, Visitando un Templo Hindú: una descripción de la experiencia subjetiva y algunas University at Albany, Universidad Estatal de interpretaciones preliminares Nueva York. Resumen. Académicos de diferentes disciplinas coinciden en que la cultura es un fenómeno Correo electrónico: [email protected] ** Estudiante del Doctorado en Administración complejo y su comprensión requiere de un análisis detallado. La complejidad inherente al y Políticas Públicas en el Rockefeller College of estudio de patrones culturales y otras estructuras sociales no se deriva de su rareza en la Public Affairs and Policy, University at Albany, sociedad. De hecho, están contenidas y representadas en eventos y artefactos de la vida cotidiana. -

Institute O F Southeast Asian Studies

Annual Report 2002–03 Institute of Southeast A sian Studies THE INSTITUTE OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES WAS ESTABLISHED AS AN AUTONOMOUS ORGANIZATION IN 1968. IT IS A REGIONAL RESEARCH CENTRE DEDICATED TO THE STUDY OF SOCIO-POLITICAL, SECURITY, AND ECONOMIC TRENDS AND DEVELOPMENTS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA AND ITS WIDER GEOSTRATEGIC AND ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT i PB EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I SEAS is a regional research centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security and economic trends in Southeast Asia and its wider geo-strategic and economic environment. Within this broad mission framework, ISEAS continued in FY 2002–03 to conduct research and analysis on academic and policy-relevant issues, public outreach activities to promote a better understanding among the public of trends and developments in the region, and networking with scholars and other research institutes. The world, in particular our region, has witnessed dramatic developments over the past few years. These have, as is to be expected, affected the research agenda of ISEAS. While the study of Southeast Asia will continue to be the focus of ISEAS research, there has been an emphasis on new issues such as political Islam, terrorism, and the economic dynamics arising from the fallout from the regional economic crisis and the rise of China. Among the major research projects initiated at the Institute were “Demographic Trends in Indonesia and their Ethnic, Religious and Political Implications”; “Ethnicity, Demography and Political Economy in Malaysia: Current Trends and Future Challenges”; “Corporate Governance in ASEAN”; and “ASEAN Economic Integration”. Also initiated were studies on the ASEAN-China, ASEAN-India, and ASEAN- Japan relationships. -

Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy

Essays on Indian Philosophy UNIVE'aSITY OF HAWAII Uf,FU:{ Essays on Indian Philosophy SHRI KRISHNA SAKSENA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS HONOLULU 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78·114209 Standard Book Number 87022-726-2 Copyright © 1970 by University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contents The Story of Indian Philosophy 3 Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy 18 Testimony in Indian Philosophy 24 Hinduism 37 Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy 51 The Jain Religion 54 Some Riddles in the Behavior of Gods and Sages in the Epics and the Puranas 64 Autobiography of a Yogi 71 Jainism 73 Svapramanatva and Svapraka!;>atva: An Inconsistency in Kumarila's Philosophy 77 The Nature of Buddhi according to Sankhya-Yoga 82 The Individual in Social Thought and Practice in India 88 Professor Zaehner and the Comparison of Religions 102 A Comparison between the Eastern and Western Portraits of Man in Our Time 117 Acknowledgments The author wishes to make the following acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published essays: "The Story of Indian Philosophy," in A History of Philosophical Systems. edited by Vergilius Ferm. New York:The Philosophical Library, 1950. "Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Are There Any Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy?" in The Philosophical Quarterly. "Testimony in Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Authority in Indian Philosophy," in Ph ilosophyEast and West. vo!.l,no. 3 (October 1951). "Hinduism," in Studium Generale. no. 10 (1962). "The Jain Religion," previously published as "Jainism," in Religion in the Twentieth Century. edited by Vergilius Ferm. -

Download Registration Number for Offline

To download the Admit Card please enter your Registration Number and Date of Birth in the format (yyyy-mm-dd). Registration Number Name of Candidate Course1 Course2 Father Name CUJET/2012/000001 JAI SHREE BHARDWAJ M.Tech. Nano Technology M.Tech. Energy Engineering KUMAR SUNDRAM BHARDWAJ CUJET/2012/000002 DHRAMENDAR KUMAR M.B.A. M.A. International Relations Harinath CUJET/2012/000003 KAJOL M.Tech. Nano Technology M.Tech. Energy Engineering SUMAN KUMAR VERMA CUJET/2012/000004 Ashutosh Kumar M.Tech. Energy Engineering M.Tech. Water Engineering & Management Madan Murari Pandey CUJET/2012/000005 RAVI VIKASH TIRKEY M.B.A. M.A. Mass Communication LEO ABHAY TIRKEY CUJET/2012/000006 Ms. SAYANTANI MANDAL M.Sc. Environmental Science Mr. NISITH RANJAN MANDAL CUJET/2012/000012 Mr OMKAR SHARAN MISHRA M.B.A. M.A. International Relations Mr KAMAL KUMAR MISHRA Mr ABHIRAM SHARAN CUJET/2012/000013 MISHRA M.Tech. Energy Engineering M.Sc. Applied Chemistry Mr KAMAL KUMAR MISHRA CUJET/2012/000014 Samatha Tejavath M.Sc. Applied Mathematics M.Tech. Nano Technology Nageswara Rao Tejavath CUJET/2012/000015 ASHUTOSH GUPTA M.Tech. Energy Engineering M.Tech. Water Engineering & Management A K GUPTA CUJET/2012/000017 Shahid Hussain Rahmatullah CUJET/2012/000019 RAJIV RANJAN M.B.A. M.A. Mass Communication SURYADEO SINGH CUJET/2012/000020 Amit Kumar M.B.A. M.A. Mass Communication Rahul Kumar CUJET/2012/000021 arman khan M.Tech. Nano Technology M.Tech. Water Engineering & Management arif khan CUJET/2012/000023 AMIT ANAND M.B.A. M.Tech. Nano Technology VEER PRASAD MAHTO CUJET/2012/000024 MOHIT MAYOOR M.Tech. -

Nationalism and Internationalism (Ca

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2012;54(1):65–92. 0010-4175/12 $15.00 # Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History 2012 doi:10.1017/S0010417511000594 Imagining Asia in India: Nationalism and Internationalism (ca. 1905–1940) CAROLIEN STOLTE Leiden University HARALD FISCHER-TINÉ Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich What is this new cult of Asianism, at whose shrine more and more incense is being offered by vast numbers of thinking Asiatics, far and near? And what has this gospel of Asianism, rightly understood and properly interpreted, to do with the merely political cry of ‘Asia for the Asiatics’? For true it is, clear to all who have eyes to see and ears to hear, that Asia is fast developing a new consciousness of her specific mission, her orig- inal contribution to Euro-America. ———Nripendra Chandra Banerji1 INTRODUCTION Asianisms, that is, discourses and ideologies claiming that Asia can be defined and understood as a homogenous space with shared and clearly defined charac- teristics, have become the subject of increased scholarly attention over the last two decades. The focal points of interest, however, are generally East Asian varieties of regionalism.2 That “the cult of Asianism” has played an important Acknowledgments: Parts of this article draw on a short essay published as: Harald Fischer-Tiné, “‘The Cult of Asianism’: Asiendiskurse in Indien zwischen Nationalismus und Internationalismus (ca. 1885–1955),” Comparativ 18, 6 (2008): 16–33. 1 From Asianism and other Essays (Calcutta: Arya Publishing House, 1930), 1. Banerji was Pro- fessor of English at Bangabasi College, Calcutta, and a friend of Chittaranjan Das, who propagated pan-Asianism in the Indian National Congress in the 1920s. -

Name of the Centre : DAV Bachra No

Name of the Centre : DAV Bachra No. Of Students : 474 SL. No. Roll No. Name of the Student Father's Name Mother's Name 1 19002 AJAY ORAON NIRMAL ORAON PATI DEVI 2 19003 PUJA KUMARI BINOD PARSAD SAHU SUNITA DEVI 3 19004 JYOTSANA KUMARI BINOD KUMAR NAMITA DEVI 4 19005 GAZAL SRIVASTVA BABY SANTOSH KUMAR SRIVASTAVA ASHA SRIVASTVA 5 19006 ANURADHA KUMARI PAPPU KUMAR SAH SANGEETA DEVI 6 19007 SUPRIYA KUMARI DINESH PARSAD GEETA DEVI 7 19008 SUPRIYA KUMARI RANJIT SHINGH KIRAN DEVI 8 19009 JYOTI KUMARI SHANKAR DUBEY RIMA DEVI 9 19010 NIDHI KUMARI PREM KUMAR SAW BABY DEVI 10 19011 SIMA KUMARI PARMOD KUMAR GUPTA SANGEETA DEVI 11 19012 SHREYA SRIVASTAV PRADEEP SHRIVASTAV ANIMA DEVI 12 19013 PIYUSH KUMAR DHANANJAY MEHTA SANGEETA DEVI 13 19014 ANUJ KUMAR UPENDRA VISHWAKARMA SHIMLA DEVI 14 19015 MILAN KUMAR SATYENDRA PRASAD YADAV SHEELA DEVI 15 19016 ABHISHEK KUMAR GUPTA SANT KUMAR GUPTA RINA DEVI 16 19017 PANKAJ KUMAR MUKESH KUMAR SUNITA DEVI 17 19018 AMAN KUMAR LATE. HARISHAKAR SHARMA RINKI KUMARI 18 19019 ATUL RAJ RAJESH KUMAR SATYA RUPA DEVI 19 19020 HARSH KUMAR SHAILENDRA KR. TIWARY SNEHLATA DEVI 20 19021 MUNNA THAKUR HIRA THAKUR BAIJANTI DEVI 21 19022 MD.FARID ANSARI JARAD HUSSAIN ANSARI HUSNE ARA 22 19023 MD. JILANI ANSARI MD.TAUFIQUE ANSARI FARZANA BIBI 23 19024 RISHIKESH KUNAL DAMODAR CHODHARY KAMLA DEVI 24 19025 VISHAL KR. DUBEY RAJEEV KUMAR DUBEY KIRAN DEVI 25 19026 AYUSH RANJAN ANUJ KUMAR DWIVEDI ANJU DWIVEDI 26 19027 AMARTYA PANDEY SATISH KUMAR PANDEY REENA DEVI 27 19028 SHIWANI CHOUHAN JAYPAL SINGH MAMTA DEVI 28 19029 SANDEEP KUMAR MEHTA -

Address by the President of India, Shri Pranab Mukherjee to Members of Both Houses of Parliament

ADDRESS BY THE PRESIDENT OF INDIA, SHRI PRANAB MUKHERJEE TO MEMBERS OF BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT January 31, 2017 Central Hall, Parliament House Honourable Members, 1. In this Basant season of renewal and resurgence, I welcome you all to this Joint Session of both Houses of Parliament. This is a historic session heralding the advancement of the Budget cycle and merger of the Railway Budget with the General Budget for the first time in independent India. We gather once again to celebrate democracy, a cherished value and culture that has prospered throughout the long history of our nation. Indeed, a culture that guides my government towards Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas. 2. The ideal of saha na vavatu, saha nau bhunaktu - May we be protected together and blessed together with bliss - has inspired our civilisation from time immemorial. This year marks the 350th birth anniversary of the great Sikh Guru - Guru Gobind Singhji. We are also observing the one thousandth birth anniversary of the great saint-philosopher Ramanujacharya. The luminous path of social transformation and reform shown by them serves as a beacon for all, and is an inspiration to my government. Page 1 of 27 3. This year marks the Centenary year of Champaran Satyagraha, which gave a new direction to our freedom struggle and channelised janashakti in the fight against colonial power. Mahatma Gandhi's ideals of Satyagraha instilled in every Indian an indomitable self-belief, and spirit of sacrifice for the larger good. This janashakti is today our greatest strength. 4. The resilience and forbearance demonstrated by our countrymen, particularly the poor, recently in the fight against black money and corruption, is remarkable. -

Namdev Life and Philosophy Namdev Life and Philosophy

NAMDEV LIFE AND PHILOSOPHY NAMDEV LIFE AND PHILOSOPHY PRABHAKAR MACHWE PUBLICATION BUREAU PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA © Punjabi University, Patiala 1990 Second Edition : 1100 Price : 45/- Published by sardar Tirath Singh, LL.M., Registrar Punjabi University, Patiala and printed at the Secular Printers, Namdar Khan Road, Patiala ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to the Punjabi University, Patiala which prompted me to summarize in tbis monograpb my readings of Namdev'\i works in original Marathi and books about him in Marathi. Hindi, Panjabi, Gujarati and English. I am also grateful to Sri Y. M. Muley, Director of the National Library, Calcutta who permitted me to use many rare books and editions of Namdev's works. I bave also used the unpubIi~bed thesis in Marathi on Namdev by Dr B. M. Mundi. I bave relied for my 0pIDlOns on the writings of great thinkers and historians of literature like tbe late Dr R. D. Ranade, Bhave, Ajgaonkar and the first biographer of Namdev, Muley. Books in Hindi by Rabul Sankritya)'an, Dr Barathwal, Dr Hazariprasad Dwivedi, Dr Rangeya Ragbav and Dr Rajnarain Maurya have been my guides in matters of Nath Panth and the language of the poets of this age. I have attempted literal translations of more than seventy padas of Namdev. A detailed bibliography is also given at the end. I am very much ol::lig(d to Sri l'and Kumar Shukla wbo typed tbe manuscript. Let me add at the end tbat my family-god is Vitthal of Pandbarpur, and wbat I learnt most about His worship was from my mother, who left me fifteen years ago. -

Breaking Free: Reflections on Stereotypes in South Asian History

BREAKING FREE Reflections on Stereotypes in South Asian History By Edith B. Lubeck or many students, regardless of age or educational background, the . while curried aromas study of South Asian history seems a daunting task given the com- and vivid textiles enrich F plex and often unfamiliar nature of the subjects under investigation. the learning environment, Of course, exotic and stereotypic images of snake charmers and mystics abound. It is often tempting to rely on mnemonically convenient formulae images of wandering (caste defined and held as a constant, a given, over millennia) as the basis mystics, snake charmers, for instruction to reduce this material to manageable proportions. Although fatalistic villagers, timeless cultural “sound bites” may be easier for the secondary school student to digest when time constraints are great and the area of study is so disconcert- and immutable caste ingly new, the risks far outweigh the benefits. The best intentions of the his- structures and religious tory classroom are undone as historical time is compressed and dynamic modes of human interaction are reduced to a flat, two-dimensional plane. hatreds leave little Threats against Muslims and Muslim-owned property in the aftermath of the room for contextualized attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon have made crystal clear investigation in the study the importance of teaching the dangers of cultural stereotyping. In the article that follows I scrutinize those paradigms that continue to of South Asian history. hold a place of privilege in many textbooks despite fresh new research from numerous scholars working within the field of South Asian history over the past two decades. -

Bani of Bhagats-Part II.Pmd

BANI OF BHAGATS Complete Bani of Bhagats as enshrined in Shri Guru Granth Sahib Part II All Saints Except Swami Rama Nand And Saint Kabir Ji Dr. G.S. Chauhan Publisher : Dr. Inderjit Kaur President All India Pingalwara Charitable Society (Regd.) Amritsar-143001 Website:www.pingalwara.co; E-mail:[email protected] BANI OF BHAGATS PART : II Author : G.S. Chauhan B-202, Shri Ganesh Apptts., Plot No. 12-B, Sector : 7, Dwarka, New Delhi - 110075 First Edition : May 2014, 2000 Copies Publisher : Dr. Inderjit Kaur President All India Pingalwara Charitable Society (Regd.) Amritsar-143001 Ph : 0183-2584586, 2584713 Website:www.pingalwara.co E-mail:[email protected] (Link to download this book from internet is: pingalwara.co/awareness/publications-events/downloads/) (Free of Cost) Printer : Printwell 146, Industrial Focal Point, Amritsar Dedicated to the sacred memory of Sri Guru Arjan Dev Ji Who, while compiling bani of the Sikh Gurus, included bani of 15 saints also, belonging to different religions, castes, parts and regions of India. This has transformed Sri Guru Granth Sahib from being the holy scripture of the Sikhs only to A Unique Universal Teacher iii Contentsss • Ch. 1: Saint Ravidas Ji .......................................... 1 • Ch. 2: Sheikh Farid Ji .......................................... 63 • Ch. 3: Saint Namdev Ji ...................................... 113 • Ch. 4: Saint Jaidev Ji......................................... 208 • Ch. 5: Saint Trilochan Ji .................................... 215 • Ch. 6: Saint Sadhna Ji ....................................... 223 • Ch. 7: Saint Sain Ji ............................................ 227 • Ch. 8: Saint Peepa Ji.......................................... 230 • Ch. 9: Saint Dhanna Ji ...................................... 233 • Ch. 10: Saint Surdas Ji ...................................... 240 • Ch. 11: Saint Parmanand Ji .............................. 244 • Ch. 12: Saint Bheekhan Ji................................