Inequality, Economic Freedom and the Olympics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies of Cancer in Humans

2. Studies of Cancer in Humans 2.1 Burkitt9slymphoma 2.1.1 Clinical features and pathology 2.1.1 .1 Clinicalfeatures The jaw is the most frequently involved site and the commonest presenting feature in patients with Burkitt's lymphoma in equatorial Africa (Burkitt, 1958, 1970a) and Papua- New Guinea (ten Seldam et al., 1966; Bukitt, 1967; Magrath ef al., 1992). The tumour frequently affects multiple jaw quadrants (Figure 5). Jaw involvement is age-dependent, occurring much more frequently in young children, since it arises in close proximity to the developing molar tooth buds. In series of cases of Burkitt's lymphoma in Uganda, 70% of children under five years of age and 25% of patients over I4 had jaw invoIve- ment (Burkitt, 1970a). Very young children who do not have overt jaw tumours often have orbital involvement (Olurin & Williams, 1972; Figure 6); some of these orbital turnours may arise in the maxilla. In general, jaw involvement appears to be more frequent in regions of higher incidence, even within equatorial Africa; however, patients from, for example, highland regions in Africa, in which the annual incidence rate of Burktt's lymphoma is muck lower, are also of higher median age, and this probably accounts for the lower frequency of jaw turnours (Buxkitt & Wright, 1966; Kitinya & Lauren, 1982). It has been suggested that the frequency of jaw tumours is decreasing in some regions of equatorial Africa, with a corresponding increase in the fraction of abdominal turnours but with no clear change in the age-related incidence (Nawnah, 1984). Abdominal invo1vement is found in a little more than half of equatorial AErican patients at presentation (Burkitt & Wright, 1963; Burkitt, 1970b; Williams, 1975) and as many as 80% of patients in other countries (Magrath, 1991, 1997). -

Select Biographical Sketches from the Notebooks of a Law Reporter

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com 600022315 V I Sir Thomas Lawrence, Pinx. S. Ayllng, Photo. anwAaii — Lois a&StMi LORD CHIEF JUSTICE, 1801. 1 1 J ► -.Li'1-'*- '" ^OOME STREET, 1867. J2./0. e SELECT BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES FROM THE Note- Books of a Law Reporter. WILLIAM HEATH BENNET, Esq., OF LINCOLN'S INN, BARRISTER-AT-LAW. LONDON: GEORGE ROUTLEDGE and SONS, BROADWAY, LUDGATE HILL. NEW YORK: 416, BROOME STREET. 1867. J2./0. e //i?, LONDON : PRINTED BY TIIOMAS SCOTT, WARWICK CCURT, HOLBOBN. 7° THE EIGHT HONORABLE WILLIAM HENRY, BARON LEIGH, STONELEIGH, LORD LIEUTENANT OF THE COUNTY OF WARWICK; CUSTOS BOTULORUMj TRUSTEE OF BUSBY SCHOOL, 4c. Sc. &c. Qgfcfff gfUtthtt WITH HIS LORDSHIP'S PERMISSION, F ESPECTFULLY DEDICATED, THE AUTHOR. PREFACE. The following Sketches — for they pretend to little more than the word imports — were, at the time they were penned, thrown off without any intention of seeking for literary fame as the result of their publication. I entreat my readers to bear this in remem brance. The earlier ones appeared in a legal weekly periodical at the end of last year, and were received with some favour by many of its readers. I was subsequently advised to collect them in a separate form, to re-cast, and to enlarge them, as better adapted for more general circulation and perusal. This I have now done, and have added perhaps the more attractive feature to the Essays — Photographic Portraits of the eminent men upon whose lives and talents I have thus ventured to comment. -

Portland Daily Press: January 19,1887

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. PRICE THREE CENTS. ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862—VOL. 24. PORTLAND, WEDNESDAY MORNING, JANUARY 19, 1887. today trom Treasurer • Report. and FOREICN. Manager MeGunnigle telegraphed County NPECIAL NOTICE'S. terms of contracts for the State and FROM WASHINGTON. ex-Commissioner Patten Congressmen of THE PORTLAND DAILY PPESS, FROM THE KENNEBEC. printing Brockton that he had a majority players COt'XTY TAX FOR 1806. for 1875-ii and 1885 and and Milliken. Brockton Published v binding the years b; Dingley who would give every day (Sundays excep' ft the The officers were elected: Jo- partially engaged, Towns. Amount. Unpaid. directing the State Treasurer to report the following and Portland a hard A meeting will 18244 PORTLAND PUBLISHING COMa <*6 of Alabama, Chas. The Recent Brutal Eviction Cases In tight. Baldwin.$ 182.44 t amount for State printing and binding seph Wheeler, president; House Thursday 043.32 at 87 The Legislature Elects a United paid Not His Tariff be held at the American Brtdgton. Kxchanoii Street. Portland, '•/fr the last four Mr. of Mr, Randall Pushing S. Hill, secretary ; A. Vanderbilt, treasurer. for the during years. Humbert, Ambrose Ireland. evening to take preliminary steps Brunswick. 1,302.71 1.662.71 DR. E. 8. Terms Donut a Year. To mall su.^ States Senator. Aroostook, who also became interested in the Bill at Present. The executive board includes Snow, 1 he organi- Capo Elizabeth. 1,0»'.16 a stock company. REED. scrlhers. Seven Dollars a Year. If S. formation of In advance. of paid had the scope of the inquiry ex- New York, chairman; Joseph Negley, be made under the char- Casco. -

Sir John Antwisel Wyons Marions Sir John Townley Wyamarus Whalley * Temp

THE ENTWISLE FAMILY – Their ancestry according to B. Grimshaw By Peter Stanford in continuation of his earlier Review of the above work. This will attempt to follow the indicated lines of descent in more detail. Part I - The Early Ancestors? A speculative chart based on the information given by Grimshaw from claimed pedigrees of other families. In an attempt to aid examination and analysis, this has been arranged by the three generations mentioned so that apparent contemporaries appear on the same line. Sir John Antwisel Wyons Marions Sir John Townley Wyamarus Whalley * temp. Wm. I of Townley temp. Wm. I (1066-1087) lord of Stanfeld lord of Whalley Thomas Entwissel Jordan = a daughter Eustas Sir Bryan Upton = Godytha = Tiburia *dau.of Sir John A. *dau.of Sir John Antwisel Elizabeth = John temp.Wm. Rufus (1087-1100) (GAP: From this point there is a gap in Grimshaw’s narrative until Robert de Entwissel of 1212. I will pick up from there in Part 2.) Locations and communications: The most obvious meeting point between these various places would be in the vicinity of Burnley, which is where Towneley is situated, on its eastern side, twelve miles from Entwistle “as the crow flies”. Horses don’t fly, but it still looks like a short enough journey for a lusty young man on horseback using cross-country tracks; or a combination of them and the Roman road which runs right through Entwistle. There is a track of prehistoric origin, since much upgraded following much the same line, and which seems to have remained in continuous use, running from Whalley to Burnley, Towneley, Mereclough, then skirting Stansfield Moor and on to Heptonstall and beyond. -

James Stansfeld & the Debates About the Repeal of the Contagious

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output James Stansfeld & the debates about the repeal of the contagious diseases acts in Britain and British In- dia 1860s-1890s https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40061/ Version: Full Version Citation: Ramsey, Christine July (2014) James Stansfeld & the debates about the repeal of the contagious diseases acts in Britain and British India 1860s-1890s. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email 1 JAMES STANSFELD & the DEBATES ABOUT THE REPEAL OF THE CONTAGIOUS DISEASES ACTS IN BRITAIN AND BRITISH INDIA, 1860s – 1890s Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Birkbeck College, University of London Christine July Ramsey 2 3 Abstract This thesis examines the life of James Stansfeld, (1820-1898), and in particular his contribution to the political reform of the Contagious Diseases Acts (CDAs) in England and in India. Stansfeld was a Liberal MP from a Unitarian (non-conformist) background who represented his native borough of Halifax during the Gladstone era. From the early 1870s onwards, eschewing high cabinet office, Stansfeld was a major force in the Commons parliamentary debates about the CDAs and their Indian equivalent. His political strategies included the building up and sustaining of popular support for repeal whilst simultaneously supporting repeal in the political arena. The thesis maps Stansfeld’s complex and radical arguments about women’s rights, particularly those of prostitutes, and his advocacy of, and practical support for, repeal of the CDAs both in England and India. -

WASHINGTON MARCH Rmber

VOLUME I. WASHINGTON MARCH rMBER For The Capital. For.The Capital. of your father, .Tim MacNair, eighteen years calmly looking out, expressed also a more and asked him what lie thought of her as an stances, but to go whithersoever the stars de- For The-Capital The Louisiana state capitol, at Baton Rouge, THE LADV OF THE TREASURY. ago this May. Bear! dear!" > emotional and more sympathetic bias. A pure REMINISCENCES OF AN OLD ACTOR. actress. THE STRIKER. is a queer, turretcd, tall edifice, resembling an Far up within that dungeon strong creed? So I said to my friend, "Give me a The Honorable Perkiomen Trappe, catching and strong woman, whose life had ripened "Where Crresus doth his hoard inclose, "Notmuch,"liereplied; "youngand pretty; letter to Mr. Jackson, and I will ride over to Slouched, and snrly, and sallow-faced, arsenel. a part of this remark; observed that .Tabel amongst the families and circles' of the best She counts the hank-notes all day long, BY DONN PIATT. got a ratherish sweet voice; no idea of acting the Hermitage and see what I can see." With a look as if something were sore misplaced. North Carolina lias a fair state capitol in a The young man Striker was seep to stride And keeps the tolly as she goes; Blake, judging by his appearance, shouldn't in condition and influence, she had never though. Compare her to Mrs. Duff! By Jove! The general ordered a horse and wrote me pretty town. Her hand upon a sponge she wets, tip the Capitol stairs at high noontide, • have buried MacNair's father, but devoured crossed to the meaner side of necessity nor to see Duff come on the stage as Isabelle in the letter desired, and in a short half hour I The state capitol of Alabama, atr Montgom- To turn the precious paper freer, My early life was made pleasant by avretired And as though at tho head of a viewless mob— him. -

Martyn Gregory

REVEALING THE EAST • Cover illustration: no. 50 (detail) 2 REVEALING THE EAST Historical pictures by Chinese and Western artists 1750-1950 2 REVEALING THE EAST Historical pictures by Chinese and Western artists 1750-1950 MARTYN GREGORY CATALOGUE 91 2013-14 Martyn Gregory Gallery, 34 Bury Street, St. James’s, London SW1Y 6AU, UK tel (44) 20 7839 3731 fax (44) 20 7930 0812 email [email protected] www.martyngregory.com 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Our thanks are due to the following individuals who have generously assisted in the preparation of catalogue entries: Jeremy Fogg Susan Chen Hardy Andrew Lo Ken Phillips Eric Politzer Geoffrey Roome Roy Sit Kai Sin Paul Van Dyke Ming Wilson Frances Wilson 4 CONTENTS page Works by European and other artists 7 Works by Chinese artists 34 Works related to Burma (Myanmar) 81 5 6 PAINTINGS BY EUROPEAN AND OTHER ARTISTS 2. J. Barlow, 1771 1. Thomas Allom (1804-1872) A prospect of a Chinese village at the Island of Macao ‘Close of the attack on Shapoo, - the Suburbs on fire’ Pen and ink and grey wash, 5 ½ x 8 ins Pencil and sepia wash, 5 x 7 ½ ins Signed and dated ‘I Barlow 1771’, and inscribed as title Engraved by H. Adlard and published with the above title in George N. Wright, China, in a series of views…, 4 vols., 1843, vol. The author of this remarkably early drawing of Macau was III, opp. p.49 probably the ‘Mr Barlow’ who is recorded in the East India Company’s letter books: on 4 August 1771 he was given permission Thomas Allom’s detailed watercolour would probably have been by the Governor and Council of Fort St George, Madras (Chennai) redrawn from an eye-witness sketch supplied to him by one of to sail from there to Macau on the Company ship Horsendon (letter the officer-artists involved in the First Opium War, such as Lt received 22 Sep. -

REFERENCES to English Surnames in 1602

REFERENCES TO ENGLISH SURNAMES 1602. cs 2505 .H62 1911 DUKE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from Duke University Libraries https://archive.org/details/referencestoengl01 hitc_0 REFERENCES TO English Surnames IN 1602 AN INDEX GIVING ABOUT 20,500 REFERENCES TO SURNAMES CONTAINED IN THE PRINTED REGISTERS OF 964 ENGLISH PARISHES DURING THE SECOND YEAR OF THE XVII. CENTURY. WITH AN APPENDIX INDEXING THE SURNAMES CONTAINED IN 186 PRINTED REGISTERS DURING 1601 (OMITTED FROM THE VOLUME FOR THAT YEAR) BY F. K. & S. HITCHING. 1911 CHAS. A. BERNAU, 17. BILLITER SQUARE BUILDINGS. LONDON. THE ST. CATHERINE PRESS 34, NORFOLK STREET STRAND, W.C. HtelSKC PREFACE TO THE VOLUME FOR j6oj (Reprinted) After even fifty years’ original research among our old records, a genealogist, interested in the history of all the branches of one English family, would know that many branches remained to be traced. Much of his time would have been wasted in searching “ likely ” registers, which, on examination, proved to contain no data for him. Experience teaches every earnest student of family history that what he needs, is not more records, but more clues as to the contents of the available records. “ Indexes and more Indexes ” is his cry, and the publisher who issues a genealogical work without an index merits (and often receives) his imprecations. No records require an Index so urgently as the Parish Registers, which record the baptisms, marriages and burials of our ancestors. These are spread over all the country, and, not only is there no general index to their contents, but there is not even an Index in each Parish to its own Registers. -

Consortium of Universities for Global Health Education Competencies

OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................................................... I Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... ii Contributing Scholars (2nd edition, 2018) ...................................................................................................... iii Peer Reviewers (2nd edition, 2018) .................................................................................................................. iii Contributing Scholars (1st edition, 2017)......................................................................................................... iv DOMAINS ........................................................................................................................................ 15 DOMAIN 1. GLOBAL BURDEN OF DISEASE .......................................................................... 2 Competency 1a ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Describe the major causes of morbidity and mortality around the world, and how the risk of disease varies with regions Competency 1b .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Describe major public health efforts to reduce disparities in global health (such as Sustainable Development Goals -

Pedigrees of the County Families of Yorkshire

Gc ,1- 942.7401 ^' '— F81p v,2 1242351 GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 01941 3043 PEDIGREES YORKSHIRE FAMILIES. PEDIGREES THE COUNTY FAMILIES YORKSHIRE JOSEPH FOSTER AND AUTIIRNTICATRD BY THE MEMBERS Of EACH FAMIL\ VOL. II.—WEST RIDING LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED FOR THE COMPILER BY W. WILFRED HEAD, P L O U O H COURT, FETTER LANE, E.G. 1874. 1242351 LIST OF PEDIGREES IN VOL. II. small type refer to fa Hies introduced into the Pedigrees, the second name being the Pedis the former appears: 'hus, Marriott will be found on reference to the Maude Pedigree. MARKHAM, of Cufforth Hall, forjierlv Becca. Nooth—Vavasour. Marriott—Maude. Norcliffe- Dalton. Marshall, of Ne\vton Kyme and Laughton— Hatfeild. North—Rockley. Martin—Edmunds. NORTON (Baron Gr.antley), of Gk.vntlev i MAUDE, OF Alverthorpe, Wakefield, &c. GATES, OF Nether Denby, and Raw'.marsh. Maude—Tempest GATES, OF Meanwoodside. Mauleverer—Laughton. Ogden—Maude. Maxwell—Midelton. Oliver—Gascoigne. Maynard—Sherd, Westby. Ormston—Aldam Melvill— Lister. Owen—Radclyffe, Rodgers. Metcalfe—More. Palmer—Roundell, Meynell—Ingram. PARKER, LATE OF WoodjWiorpe, MICKLETHWAITE, OF INGBIRCHWORTH, .\rdslev Parker—Lister, Walker. HOUSE, &C. (jft'Vol. 3.) St. Paul—Bosvile. MIDDELTON, of Stockeld a.\d Miiuielto.N' Lodge. Pease—Aldam. Milbanke—Wentworth, Nos. i and 2. Pedwardyn— Savile of Thornhill. MILNER, of Burton Grange. Pemberton—Stapleton. MILNER, of Pudsev, now of Nun Arpleto.n. Perceval—Westby. MlLNESj of Wakefield and (Baron Houghton) Percy—Foljambe, Heber. Fryston. Pickford-Radcliffe. Montagu—Wortley. Pickford, of Macclesfield—Radclyffe. Moore, of Frampton—More, of Barnborough. Pigot—Wood, of Hickleton. Moore—Foljambe. Pigott— Fairfax Moorsome —Maude. PILKINGTON, of Chevet Park, \-c. -

The British Division of the International Academy of Pathology

The British Division of the International Academy of Pathology www.bdiap.org JANUARY 2012 BDIAP PRESIDENT PROFESSOR NEIL A SHEPHERD Inside this Issue 2011 has been a special year for the President’s Column: 1-3 BDIAP. It has been our 50th Anniver- sary. The Division was initiated back Message from the IAP in 1961 by Dr George Cunningham. President 3-5 His profound influence on the Soci- Cunningham and ety, in its early days, is, of course, President’s Medals 6 celebrated in the naming of a BDIAP Medal, acknowledging those who History of the BDIAP make a substantial contribution to the Prof. Chris Elston 7-8 BDIAP. This year, as seen elsewhere in this Newsletter, the Cunningham Histopathology - Past, Medal was awarded to Ms Elizabeth Present and Future Whelan, who has made such a huge Prof. Michael Wells 9-14 contribution, over many years, to that very important organ of the BDIAP, Professional Challenges for Pathologists, Prof. Sir its journal Histopathology. James Underwood 15-16 Through the years there has been a The Future of Pathology The Next 50 Years, procession of high profile Presidents Prof. Peter Furness 17-23 of the BDIAP. One sneak at the Presi- dential chain of office (and I do, quite often) identifies the calibre of these th BDIAP Sponsored Presidents, which humbles me a lot. As I said on the day of the 50 Anni- Education, Dr Udovicic- versary celebration, it reads like a ―Who‘s who‖ and it makes me feel a bit Gagula & Prof. Andrew like a ―Who‘s he?‖. -

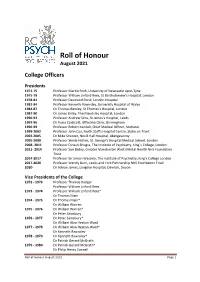

Roll of Honour August 2021

Roll of Honour August 2021 College Officers Presidents 1971-75 Professor Martin Roth, University of Newcastle upon Tyne 1975-78 Professor William Linford Rees, St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London 1978-81 Professor Desmond Pond, London Hospital 1981-84 Professor Kenneth Rawnsley, University Hospital of Wales 1984-87 Dr Thomas Bewley, St Thomas’s Hospital, London 1987-90 Dr James Birley, The Maudsley Hospital, London 1990-93 Professor Andrew Sims, St James’s Hospital, Leeds 1993-96 Dr Fiona Caldicott, Uffculme Clinic, Birmingham 1996-99 Professor Robert Kendell, Chief Medical Officer, Scotland 1999-2002 Professor John Cox, North Staffs Hospital Centre, Stoke on Trent 2002-2005 Dr Mike Shooter, Nevill Hall Hospital, Abergavenny 2005-2008 Professor Sheila Hollins, St. George’s Hospital Medical School, London 2008- 2011 Professor Dinesh Bhugra, The Institute of Psychiatry, King`s College, London 2011- 2014 Professor Sue Bailey, Greater Manchester West Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust 2014-2017 Professor Sir Simon Wessely, The Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London 2017-2020 Professor Wendy Burn, Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust 2020- Dr Adrian James, Langdon Hospital, Dawlish, Devon Vice Presidents of the College 1972 - 1973 Professor Thomas Rodger Professor William Linford Rees 1973 - 1974 Professor William Linford Rees* Dr Thomas Main 1974 - 1975 Dr Thomas Main* Dr William Warren 1975 - 1976 Dr William Warren* Dr Peter Sainsbury 1976 - 1977 Dr Peter Sainsbury* Dr William Alan Heaton-Ward 1977 - 1978 Dr William Alan