A Travesty of Justice: the Case of the Grenada 17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perspectives on the Grenada Revolution, 1979-1983

Perspectives on the Grenada Revolution, 1979-1983 Perspectives on the Grenada Revolution, 1979-1983 Edited by Nicole Phillip-Dowe and John Angus Martin Perspectives on the Grenada Revolution, 1979-1983 Edited by Nicole Phillip-Dowe and John Angus Martin This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Nicole Phillip-Dowe, John Angus Martin and contributors Book cover design by Hugh Whyte All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5178-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5178-7 CONTENTS Illustrations ................................................................................................ vii Acknowledgments ...................................................................................... ix Abbreviations .............................................................................................. x Introduction ................................................................................................ xi Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Citizens and Comrades in Arms: The Congruence of Fédon’s Rebellion and the Grenada -

The Eagle 1934 (Michaelmas)

THE EAGLE u1 /kIagazine SUPPOR TED BY MEMBERS OF Sf John's College r�-� o�\ '). " ., .' i.. (. .-.'i''" . /\ \ ") ! I r , \ ) �< \ Y . �. /I' h VOLUME XLVIII, No. 214 PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY MCMXXXV CONTENTS PAGE Three Sculptured Monuments in St John's 153 Facit Indignatio Versus 156 Ceasing in Time to Sing 157 Music in New Guinea 158 "What bugle from the pine wood " 170 Frustration 172 College Chronicle: Lady Margaret Boat Club 172 Cricket 174 Hockey 176 Swimming 176 Athletics 177 Lawn Tennis 177 Rugby Fives . 178 The Natural Science Club 178 Chess . 179 The Law Society . 179 The Medical Society 180 The Nashe Society 181 The Musical Society r82 The Theological Society r83 The Adams Society 183 College Notes . 184 Obituary . 189 The Library: Additions 201 Illustrations : The Countess of Shrewsbury frontispiece Monument of Hugh Ashton fa cing p. 154 Monument of Robert Worsley " 155 Iatmul man playing flute 158 PI. I .THE EAGLE ������������������������������� VOL. XLVIII December I 934 No. 2I4 ������������������������������� THREE SCULPTURED MONUMENTS IN ST JOHN'S [The following notes, by Mrs Arundell Esdaile, are reprinted by per mission ofNE the Cambridge Antiquarian Society.] of the most notable tombs in Cambridge is that of OHugh Ashton (PI. H) who built the third chantry in the Chapel and desired to be buried before the altar. This canopied monument, with its full-length effigy laid on a slab above a cadaver, is an admirable example of Gothic just touched by Renaissance feeling and detail. The scheme, the living laid above the dead, is found in the tomb of William of Wykeham and other fifteenth-century works; but it persisted almost until the Civil War, though the slab, in some of the finest seventeenth-century examples, is borne up by mourners or allegorical figures, as at Hatfield. -

The Edinburgh Gazette, September 22, 1931. 1077

THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, SEPTEMBER 22, 1931. 1077 Foreign Office, Civil Service Commission, July 21, 1931. September 18, 1931. The KING has been pleased to approve of: — The Civil Service Commissioners hereby give Doctor Jerzy Adamkiewicz, as Consul-General notice that an Open Competitive Examination of Poland at Montreal for Newfoundland. for situations as Female Sorting Assistant in the General Post Office, London, will be held in London, commencing .on the 30th December 1931, under the Regulations dated the 26th September 1930, and published in the Edin- burgh Gazette of the 3rd October 1930. Foreign Office, August 1, 1931. Appointments will be offered to not fewer than 25 of the candidates highest on the list, The KING has been graciously pleased to provided they obtain the necessary aggregate appoint: — of marks and are duly qualified in other Edward Homan Mulock, Esquire, to be Com- respects. mercial Secretary, First Grade, at His No person will be admitted to Examination Majesty's Embassy at Eome, with the local from whom the Secretary of the Civil Service rank of Commercial Counsellor. Commission has not received, on or before the 12th November 1931, an application, in the Candidate's own handwriting, on a prescribed form, which may be obtained from the Secre- tary at once. Foreign Office, September 11, 1931. The KING has been pleased to approve of: — Mr. A. M. Hamilton, as Consul of Belgium at NATIONAL HEALTH INSURANCE Belfast for Northern Ireland; ACT, 1924. Monsieur E. Dumon, as Consul of Belgium at Notice is hereby given under the Rules Sunderland, with jurisdiction over the Publication Act, 1893, that it is proposed by County of Durham, with the exception of the National Health Insurance Joint Commit- . -

NJM 1973 Manifesto

The Manifesto of the New Jewel Movement The New Jewel Movement Manifesto was issued late in 1973 by the New Jewel Movement party of Grenada. The Manifesto was presented at the Conference on the Implications of Independence for Grenada from 11-13 January 1974. Many believe the Manifesto was co-written by Maurice Bishop and Bernard Coard. According to Sandford, in August 1973, “the NJM authorized Bishop to enlist the services of Bernard Coard in drafting a manifesto . .” In 1974 Coard was part of the Institute of International Relations and would not return to Grenada to take up residency until September 1976; nevertheless, he traveled between islands. Scholar Manning Marable asserts this: “The NJM's initial manifesto was largely drafted by MAP's major intellectual, Franklyn Harvey, who had been influenced heavily by the writings of [CLR] James.” Another influence is attributed to Tanzanian Christian Socialism. Below is a combination of the text from versions of the Manifesto. The Manifesto begins with this introduction: MANIFESTO OF THE NEW JEWEL MOVEMENT FOR POWER TO THE PEOPLE AND FOR ACHIEVING REAL INDEPENDENCE FOR GRENADA, CARRIACOU, PETIT MARTINIQUE AND THE GRENADIAN GRENADINES (1973) ALL THIS HAS GOT TO STOP Introduction The people are being cheated and have been cheated for too long--cheated by both parties, for over twenty years. Nobody is asking what the people want. We suffer low wages and higher cost of living while the politicians get richer, live in bigger houses and drive around in even bigger cars. The government has done nothing to help people build decent houses; most people still have to walk miles to get water to drink after 22 years of politicians. -

Chasing the Chimera: the Rule of Law in the British Empire and the Comparative Turn in Legal History

Chasing the Chimera: The Rule of Law in the British Empire and the Comparative Turn in Legal History John McLaren This article compares the imposition, application and evolution of the Rule of Law in colonial territories and their populations within the British Empire as evidence of a ‘Comparative Turn’ in exploring metro- politan and colonial legal cultures and their interrelationships. The purpose of the study is not primarily to either justify or criticise that concept, but to suggest that its complexity, contingency and controversy provides fertile soil for research relating to law and justice, and their ideologies across the British Empire. Elsewhere there might be the sultan’s caprice, the lit de justice, judicial torture, the slow-grinding mills of the canon law’s bureaucracy, and the auto-da-fé of the Inquisition. In England, by contrast, king and magis- trates were beneath the law, which was the even-handed guardian of every Englishman’s life, liberties, and property. Blindfolded Justice weighed all equitably in her scales. The courts were open, and worked by known and due process. Eupeptic fanfares such as those on the unique blessings of being a free-born Englishman under the Anglo-Saxon-derived common law were omnipresent background music. Anyone, from Lord Chancellors to rioters, could be heard piping them (though for very different purposes).1 There is inherent value and potential in comparing the legal cultures of former British colonial territories to demonstrate the processes of the translation of legal culture and ideology, not only from the metropolis to the colonies, but between the colonies themselves, and the institutional and personal networks and trajectories that facilitated these movements. -

Britain and Menorca in the Eighteenth Century

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Britain and Menorca in the eighteenth century Thesis How to cite: Britain and Menorca in the eighteenth century. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 1994 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000e060 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Britain and Menorca in the Eighteenth Century David Whamond Donaldson MA Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Arts Faculty The Open University August 1994 Volume Three of Three Chapter Eight The Defence of Menorca - Threats and Losses----- p. 383 Chapter Nine The Impact of the British presence in Menorca p. 426 Chapter Ten The Final Years,, ý,.. p. 486 Epilogue and Conclusion' p. 528 Appendix A Currency p. 544 Appendix B List of holders of major public offices p. 545 Appendix C List of English words in Nenorqui p. 546 Bibliography p. 549 Chapter Eight. The Defence of Menorca - Threats and Losses. Oh my country! Oh Albion! I doubt thou art tottering on the brink of desolation this dayl The nation is all in a foment u on account of losing dear Minorca. This entry for 18 July 1756 in the diary of Thomas Turner, a Sussex shopkeeper, encapsulated the reaction of the British ýeen public to the news that Menorca had lost to the French at a time when, such was the vaunted impregnability of Fort St. -

The 1983 Invasion of Grenada

ESSAI Volume 7 Article 36 4-1-2010 The 1983 nI vasion of Grenada Phuong Nguyen College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Nguyen, Phuong (2009) "The 1983 nI vasion of Grenada," ESSAI: Vol. 7, Article 36. Available at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol7/iss1/36 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at [email protected].. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized administrator of [email protected].. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nguyen: The 1983 Invasion of Grenada The 1983 Invasion of Grenada by Phuong Nguyen (History 1140) he Invasion of Grenada in 1983, also known as Operation Urgent Fury, is a brief military operation that was heralded as a great triumph by some and harshly criticized by others. TAlthough the Invasion of Grenada is infrequently discussed today in modern politics, possibly due to the brevity and minimal casualties, it provides valuable insight into the way foreign policy was conducted under the Reagan administration towards the end of the Cold War. The invasion did not enjoy unanimous support, and the lessons of Grenada can be applied to the global problems of today. In order to understand why the United States intervened in Grenada, one must know the background of this small country and the tumultuous history of Grenadian politics, which led to American involvement. Grenada is the smallest of the Windward Islands of the Caribbean Sea, located 1,500 miles from Key West, Florida, with a population of 91,000 in 1983 and a total area of a mere 220 square miles (Stewart 5). -

The Edinburgh Gazette, March 12, 1915

390 THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, MARCH 12, 1915 Lieutenant-Colonel Stephen Penfold, Mayor Captain Clive Oldnall Long Phillipps-Wolley, of Folkestone. of Victoria, British Columbia. Walter Trower, Esq. William Price, Esq., of Quebec. Henry Urwick, Esq., of Worcester. James Glenny Wilson, Esq., President - of Herbert Ashcombe Walker, Esq., General the Board of Agriculture in the Dominion Manager of the London and South-Western of'New Zealand. Railway. Alfred William Watson, Esq. INDIAN LIST. (To take effect as from the 1st January 1915). Joseph John Heaton, Esq., Indian Civil Service, a Puisne Judge of the High Court Robert Stewart Johnstone, Esq., lately of Judicature in Bombay. Chief Justice of Grenada, was unable to George Cunningham Buchanan. Esq., C.I.E., attend, and will be dubbed at a later date. Chairman and Chief Engineer of the Com- missioners for the Port of Rangoon, Burma. Donald Campbell Johnstone, Esq., Indian The KING has also been pleased, by Letters Civil Service, Judge of the Chief Court of Patent under the Great Seal of the United the Punjab. Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, bearing Loraine Geddes Dunbar, Esq., Secretary date the 1st January 1915, to confer the dignity and Treasurer of the Bank of Bengal, of a Knight of the said United Kingdom upon :— Calcutta. John Gibson, Esq., of Aberystwith. John Hubert Marshall, Esq., C.I.E., Director- General of Archaeology in India. • v ^ COLONIAL LIST. Satyendra Prasanna Siiiha, Esq., Barrister- at-Law, a Member of the Legislative James Thomson Broom, Esq., Chairman of Council of the Governor of Bengal. the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce. -

AN AQUEOUS TERRITORY This Page Intentionally Left Blank an AQUEOUS TERRITORY

AN AQUEOUS TERRITORY This page intentionally left blank AN AQUEOUS TERRITORY Sailor Geographies and New Granada’s Transimperial Greater Ca rib bean World ernesto bassi duke university press Durham and London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Bassi, Ernesto, [date] author. Title: An aqueous territory : sailor geographies and New Granada’s transimperial greater Ca rib bean world / Ernesto Bassi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016023570 (print) lccn 2016024535 (ebook) isbn 9780822362203 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362401 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373735 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Geopolitics— Caribbean Area. | Ca rib bean Area— Bound aries. | Ca rib bean Area— Commerce. | Ca rib bean Area— History. | Ca rib bean Area— Politics and government. | Imperialism. Classification: lcc f2175.b37 2017 (print) | lcc f2175 (ebook) | ddc 320.1/2— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016023570 Cover art: Detail of Juan Álvarez de Veriñas’s map of the southern portion of the transimperial Greater Caribbean. Image courtesy of Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain (MP-Panama, 262). TO CLAU, SANTI, AND ELISA, mis compañeros de viaje This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS acknowl edgments ix introduction: Uncovering Other Pos si ble -

Grenada's New Jewel Movement

INTERNATIONAL Lessons of losing power Grenada's New Jewel Movement In October 1983 a US force of 80 000 marines invaded the Caribbean island of Grenada bringing to an abrupt end the five year revolutionary experiment of the New Jewel Movement (NJM) led by Maurice Bishop. Although condemned by anti-imperialist and progressive forces world-wide, the American invasion was apparently welcomed by wide sections of the Grenadan population. DIDACUS JULES, Deputy Secretary for Education in the Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG) of Grenada, 1979-83, spoke to Barbara Creecy* about the lessons of losing power in Grenada. _ For 25 years prior to 1979, l/T .Yr|Vl|YriYitV^[V questioning who were the ::::;:::::::;::; ••:::;:::::>;::;::: Grenada was governed by li.. ..•;;; black faces in office and Eric Gairy who assumed whether they were serving leadership of the 1951 revol the interests of the black •jT\ d£»i_ ution when the masses rose North masses. against the bad working con ^ America There were a number of in ditions they faced. Although dependent community-based he was initially popularly Grenada militant youth organisations. elected, Gairy degenerated One such was the Movement into a despot using re ^t for the Assemblies of the pression and superstition to People which had a black- remain in power. Caribbean &-} power-cum-socialist In the early 1970s, the Ca orientation, partly influenced ribbean, influenced by the by Tanzania's Ujamaa social upheavals in the United States, ism. There was also an organ was swept by a wave of Black South isation called the JEWEL Power. To many young Carib America I/" (Joint Movement for Educa bean intellectuals. -

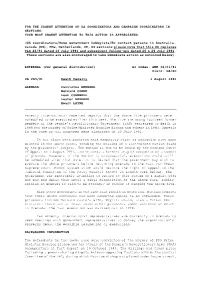

Your Most Urgent Attention to This Action Is Appreciated

FOR THE URGENT ATTENTION OF UA COORDINATORS AND CAMPAIGN COORDINATORS IN SECTIONS: YOUR MOST URGENT ATTENTION TO THIS ACTION IS APPRECIATED. (UA Coordinators/Home Government Lobbyists/EC contact persons in Australia, Canada (ES), FRG, Netherlands, UK, US sections please note that this UA replaces TLX 46/91 dated 16 July 1991 and subsequent follow-ups dated 26 & 29 July 1991. These sections are also encouraged to take immediate action as outlined below). EXTERNAL (for general distribution) AI Index: AMR 32/01/91 Distr: UA/SC UA 265/91 Death Penalty 1 August 1991 GRENADA: Callistus BERNARD Bernard COARD Leon CORNWALL Lester REDHEAD Ewart LAYNE Amnesty International received reports that the above five prisoners were scheduled to be executed earlier this week. The five are among fourteen former members of the People's Revolutionary Government (PRG) sentenced to death in 1986 for the murder of Prime Minister Maurice Bishop and others in 1983. Appeals in the case of all fourteen were dismissed on 10 July 1991. It has since been reported that temporary stays of execution have been granted in the above cases, pending the hearing of a last-minute motion filed by the prisoners' lawyers. The motion is due to be heard by the Grenada Court of Appeal on 7 August 1991, and it seeks a further stay of execution on a number of grounds. However, if the motion is unsuccessful, executions could still be scheduled after that date. It is feared that the government may wish to execute the above prisoners before returning Grenada to the East Caribbean Supreme Court (ECSC) system which would restore the right of appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) in London (see below). -

Reviewarticle the Coards and the Grenada Revolution

New West Indian Guide 94 (2020) 293–299 nwig brill.com/nwig Review Article ∵ The Coards and the Grenada Revolution Jay R. Mandle Department of Economics, Colgate University, Hamilton NY, USA [email protected] Joan D. Mandle Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Colgate University, Hamilton NY, USA [email protected] Bernard Coard, The Grenada Revolution: What Really Happened? The Grenada Revolution Volume 1. Kingston and St. George’s: McDermott Publishing, 2017. xx + 349 pp. (Paper US$18.50) Bernard Coard, Forward Ever: Journey to a New Grenada. The Grenada Revolu- tion Volume 2. Kingston and St. George’s: McDermott Publishing, 2018. vii + 386 pp. (Paper US$19.50) Bernard Coard, Skyred: A Tale of Two Revolutions. The Grenada Revolution Vol- ume 3. Kingston and St. George’s: McDermott Publishing, 2020. xx + 388 pp. (Paper US$19.50) Phyllis Coard, Unchained: A Caribbean Woman’s Journey Through Invasion, Incarceration & Liberation. Kingston and St. George’s: McDermott Publishing, 2019. viii + 292. (Paper US$14.50) Each of these volumes supplies the kind of detailed information concerning the Grenada Revolution that only its participants could have provided. As such, © jay r. mandle and joan d. mandle, 2020 | doi:10.1163/22134360-09403001 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NCDownloaded4.0 license. from Brill.com09/27/2021 01:36:25PM via free access 294 review article the books are invaluable for anyone interested in the Revolution’s many accom- plishments or its tragic demise.1 In Skyred: A Tale of Two Revolutions, Bernard Coard (hereafter BC) details Eric Gairy’s ascendency, as well as the growth in opposition to his rule that culminated with the military victory of the New Jewel Movement (NJM) on March 13, 1979.