How My Light Is Spent: the Memoirs of Dewitt Stetten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holland America's Shore Excursion Brochure

Continental Capers Travel and Cruises ms Westerdam November 27, 2020 shore excursions Page 1 of 51 Welcome to Explorations Central™ Why book your shore excursions with Holland America Line? Experts in Each Destination n Working with local tour operators, we have carefully curated a collection of enriching adventures. These offer in-depth travel for first- Which Shore Excursions Are Right for You? timers and immersive experiences for seasoned Choose the tours that interest you by using the icons as a general guide to the level of activity alumni. involved, and select the tours best suited to your physical capabilities. These icons will help you to interpret this brochure. Seamless Travel Easy Activity: Very light activity including short distances to walk; may include some steps. n Pre-cruise, on board the ship, and after your cruise, you are in the best of hands. With the assistance Moderate Activity: Requires intermittent effort throughout, including walking medium distances over uneven surfaces and/or steps. of our dedicated call center, the attention of our Strenuous Activity: Requires active participation, walking long distances over uneven and steep terrain or on on-board team, and trustworthy service at every steps. In certain instances, paddling or other non-walking activity is required and guests must be able to stage of your journey, you can truly travel without participate without discomfort or difficulty breathing. a care. Panoramic Tours: Specially designed for guests who enjoy a slower pace, these tourss offer sightseeing mainly from the transportation vehicle, with few or no stops, and no mandatory disembarkation from the vehicle Our Best Price Guarantee during the tour. -

Appetizers First Course Salads Grilled Fish & Crustacean on Saturdays

APPETIZERS Assorted finger foods Brazilian cheese rolls, fine tapioca breads, homemade breads baked in our clay oven Starters per person (optional) Crunchy wanton with cod brandade (6 units) Grana Padano or Manchego cheese Codfish cake (8 units) Filet Mignon appetizer Bruschetta of the day Pork sausage with chimichurri Potato chips with roast beef and Dijon mustard (6 units) Small golden cubes of tapioca served with pepper jelly (10 units) FIRST COURSE SALADS Steak Tartare Green knife-chopped, served with soufflé potatoes green leaves, apple, avocado, and fennel vinaigrette Beef carpaccio with rocket leaves, Parmesan cheese Rubaiyat Salad and Dijon mustard dressing fresh mixed greens, carrots, cherry tomatoes, hearts of palm, wonton crispies, and buffalo Pork ribs mozzarella slowly roasted, served with barbecue sauce Julienne Coal-grilled goat Provoleta Lettuce, tomato, hearts of palm, carrot, “Cabaña Las Lilas” bacon, shoestring potato, wonton crispies, Palm-heart Grana Padano, and mustard dressing baked in a wood oven with sun-dried tomatoes Palm-heart & Watercress Palm-heart capellini with mustard & lime vinaigrette with parmesan sauce, iberian ham and green Caesar aparagus Funghi carpaccio confit in thin slices, served with watercress leaves and white truffle olive oil ON SATURDAYS Brazilian Feijoada (with all trimmings) with baby pork from the Rubaiyat Farm and dessert table* (per person) Brazilian Feijoada (with all trimmings) To Go *Half-price for children 5-12 years old. Free for children 4 and under. GRILLED FISH & CRUSTACEAN -

Biochemistrystanford00kornrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Program in the History of the Biosciences and Biotechnology Arthur Kornberg, M.D. BIOCHEMISTRY AT STANFORD, BIOTECHNOLOGY AT DNAX With an Introduction by Joshua Lederberg Interviews Conducted by Sally Smith Hughes, Ph.D. in 1997 Copyright 1998 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Arthur Kornberg, M.D., dated June 18, 1997. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Fall 2009 Newsletter

12/5/2016 Society of American Archivists Go Home The Archives Profession About Us Education & Events Publications Members Groups Log in / Log out Manuscript Repositories Newsletter Print this page Join SAA Fall 2009 Contact us Society of Section Updates American Archivists From the Chair 17 North State Street Suite 1425 Annual Meeting Minutes Chicago, IL 606023315 tel 312/6060722 2009 Membership Survey Results fax 312/6060728 tollfree 866/7227858 News from Members Home Annual Meeting Hargis Papers Document Birth of Religious Right Bylaws Celebrating the Lincoln Collection in Fort Wayne Leadership American College of Surgeons Archives Digital Collections Newsletter Resources University of South Alabama Archives Receives Funding for Photographic Collections Joel Fletcher Papers Available at Tulane University Papers of Julia Randall Available at Hollins University Recent Acquisitions: New Civil War Diaries at Virginia Tech News from the Schlesinger Library The Ashes of Waco Digital Collection The University of Texas M.D. Anderson President's Office Records Now Open for Research Ransom Center Receives NEH Grant to Preserve Papers of Morris Ernst Special Collections Digitized at Swem Library, College of William and Mary Online Astronauts' Papers Illustrate Purdue's Place in Space Leadership and Next Newsletter Deadline Section Updates From the Chair Mat Darby As happens every fall, the Section Steering Committee has been busy reviewing several proposals submitted to us for endorsement, and we look forward to letting you know more about our selections in the months ahead. We are also in the early stages of planning for next year's Section meeting in D.C. -

William Albert Noyes

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WILLIAM ALBERT NOYES 1857—1941 A Biographical Memoir by ROGER ADAMS Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1952 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. WILLIAM ALBERT NOYES1 BY ROGER ADAMS William Albert Noyes was born November 6, 1857 on a farm near Independence, Iowa. He was the seventh generation of the Noyes family in America, being descended from Nicholas Noyes who came with his elder brother, James, from Choulder- ton, Wiltshire, in 1633. Their father had been a clergyman but had died before the sons left England. The two brothers settled first in Medford, Massachusetts but in 1655 moved to Newbury. Samuel, of the third generation in this direct line, moved to Abington about 1713 and there he and the succeeding generations lived for over one hundred and forty years. Spencer W. Noyes, the great grandson of Samuel, was ad- mitted as a student to Phillips Academy at Andover, Massachu- setts, March 21, 1837. He married Mary Packard-related to the famous family of shoe manufacturers-and they had three children when they left: Abington and migrated to Iowa in 185j. When the father with his family went west to open up a home- stead, he found conditions typical of the prairies and life was necessarily primitive. In the east he had been a cobbler by trade so had had little experience working the land. The early years were difficult ones because of the hard work in establishing a farm home, getting land into cultivation, raising food and storing sufficient for winter needs. -

The April Meeting in New York

THE APRIL MEETING IN NEW YORK The five hundred fifty-seventh meeting of the American Mathe matical Society was held on Thursday through Saturday, April 23- 25, 1959 at the Hotel New Yorker in New York, New York. About 600 persons attended, including 420 members of the Society. There was a Symposium on Nuclear Reactor Theory, sponsored by the Society with the financial aid of the Office of Ordnance Re search, with sessions on Thursday morning and afternoon and Friday morning and afternoon. The program committee consisted of Profes sor E. P. Wigner, Chairman, and Professor Garrett Birkhoff, Dr. H. L. Garabedian, Dr. S. M. Ulam, and Dr. J. E. Wilkins. The papers presented at the Symposium are to be published by the Society under the editorship of Professors Birkhoff and Wigner as volume 11 in The Proceedings of the Symposia in Applied Mathematics. There was a Symposium on Finite Groups, sponsored by the Soci ety with the financial aid of Project FOCUS of the Institute for Defense Analyses, with sessions on Thursday morning and afternoon and Friday morning. The program committee consisted of Professor A. A. Albert, Chairman, Professors Walter Feit, Marshall Hall, I. N. Herstein, and Irving Kaplansky. The papers presented at the Sym posium are to be published by the Society as a book under the editor ship of Professors Albert and Kaplansky. By invitation of the Committee to Select Hour Speakers for East ern Sectional Meetings, Professor Jun-ichi Igusa of The Johns Hop kins University delivered an address entitled On the Kroneckerian model for elliptic modular functions on Saturday morning. -

*Revelle, Roger Baltimore 18, Maryland

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES July 1, 1962 OFFICERS Term expires President-Frederick Seitz June 30, 1966 Vice President-J. A. Stratton June 30, 1965 Home Secretary-Hugh L. Dryden June 30, 1963 Foreign Secretary-Harrison Brown June 30, 1966 Treasurer-L. V. Berkner June 30, 1964 Executive Officer Business Manager S. D. Cornell G. D. Meid COUNCIL *Berkner L. V. (1964) *Revelle, Roger (1965) *Brown, Harrison (1966) *Seitz, Frederick (1966) *Dryden, Hugh L. (1963) *Stratton, J. A. (1965) Hutchinson, G. Evelyn (1963) Williams, Robley C. (1963) *Kistiakowsky, G. B. (1964) Wood, W. Barry, Jr. (1965) Raper, Kenneth B. (1964) MEMBERS The number in parentheses, following year of election, indicates the Section to which the member belongs, as follows: (1) Mathematics (8) Zoology and Anatomy (2) Astronomy (9) Physiology (3) Physics (10) Pathology and Microbiology (4) Engineering (11) Anthropology (5) Chemistry (12) Psychology (6) Geology (13) Geophysics (7) Botany (14) Biochemistry Abbot, Charles Greeley, 1915 (2), Smithsonian Institution, Washington 25, D. C. Abelson, Philip Hauge, 1959 (6), Geophysical Laboratory, Carnegie Institution of Washington, 2801 Upton Street, N. W., Washington 8, D. C. Adams, Leason Heberling, 1943 (13), Institute of Geophysics, University of Cali- fornia, Los Angeles 24, California Adams, Roger, 1929 (5), Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois Ahlfors, Lars Valerian, 1953 (1), Department of Mathematics, Harvard University, 2 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge 38, Massachusetts Albert, Abraham Adrian, 1943 (1), 111 Eckhart Hall, University of Chicago, 1118 East 58th Street, Chicago 37, Illinois Albright, William Foxwell, 1955 (11), Oriental Seminary, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore 18, Maryland * Members of the Executive Committee of the Council of the Academy. -

MAY 03 Nucleus Sp-LAST

DED UN 18 O 98 F yyyy N yyyy Y O T R E I T H C E O yyyyN A E S S S L T A E A C R C I yyyyN S M S E E H C C T N IO A May 2003 Vol. LXXXI, No. 9 yyyyC N • AMERI Monthly Meeting Education Night at B.U. Guy Crosby speaks on Chemistry of Nutrition Election 2003 Election of candidates for 2004 Book Review Quantum Leaps in the Wrong Direction, by C. M. Wynn and A. W. Wiggins Historical Note Edward Frankland’s Crusade for Clean Water in the 19th Century template group. If this were true, then this end, a simple molecular modeling Meeting virtually any ring system which ful- exercise was undertaken to compare filled this requirement would lead to a the differences between our best com- series of potent inhibitors pound and those reported by Merck. Report We selected the 1H-pyrrole ring The simple overlay of these molecules From the April 10, 2003 Esselen system as our starting template to test revealed the presence of a methyl Award Address this hypothesis, primarily because group in the Merck compound in a these could readily be prepared from region of space not occupied by our The Discovery And 1,4-diketones through the classical inhibitors. Development Of Lipitor‚ Paal-Knorr condensation and these 1,4- To determine the importance of (Atorvastatin Calcium) diketones, in turn, were potentially occupying this space, bromine and available possessing a wide variety of chlorines were introduced into the 3- Bruce D. -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors. -

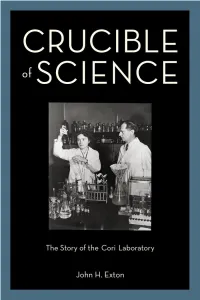

Crucible of Science: the Story of the Cori Laboratory

Crucible of Science This page intentionally left blank Crucible of Science THE STORY OF THE CORI LABORATORY JOHN H. EXTON 3 3 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Th ailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 © Oxford University Press 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitt ed by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. CIP data is on fi le at the Library of Congress ISBN 978–0–19–986107–1 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Dedicated to Charles Rawlinson (Rollo) Park This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix I n t r o d u c t i o n xi 1. -

Lexique Nautique Anglais-Français

,Aa « DIX MILLE TERMES POUR NAVIGUER EN FRANÇAIS » Lexique nautique anglais français© ■ Dernière mise à jour le 15.5.2021 ■ Saisi sur MS Word pour Mac, Fonte Calibri 9 ■ Taille: 3,4 Mo – Entrées : 10 114 – Mots : 180 358 ■ Classement alphabétique des entrées anglaises (locutions ou termes), fait indépendamment de la ponctuation (Cet ordre inhabituel effectué manuellement n’est pas respecté à quelques endroits, volontairement ou non) ■ La lecture en mode Page sur deux colonnes est fortement suggérée ■ Mode d’emploi Cliquer sur le raccourci clavier Recherche pour trouver toutes les occurrences d’un terme ou expression en anglais ou en français AVERTISSEMENT AUX LECTEURS Ce lexique nautique anglais-français est destiné aux plaisanciers qui souhaitent naviguer en français chez eux comme à l’étranger, aux amoureux de la navigation et de la langue française; aux instructeurs, moniteurs, modélistes navals et d’arsenal, constructeurs amateurs, traducteurs en herbe, journalistes et adeptes de sports nautiques, lecteurs de revues spécialisées, clubs et écoles de voile. L’auteur remercie les généreux plaisanciers qui depuis plus de quatre décennies ont fait parvenir corrections et suggestions, (dont le capitaine Lionel Cormier de Havre-Saint-Pierre qui continue à fidèlement le faire) et il s’excuse à l’avance des coquilles, erreurs et doublons résiduels ainsi que du classement alphabétique inhabituel ISBN 0-9690607-0-X © 28.10.19801 LES ÉDITIONS PIERRE BIRON Enr. « Votre lexique est très apprécié par le Commandant Sizaire, autorité en langage maritime. Je n’arrive pas à comprendre que vous ne trouviez pas de diffuseur en France pour votre lexique alors que l’on manque justement ici d’un ouvrage comme le vôtre, fiable, très complet, bien présenté, très clair. -

A Tale of Two Hormones

LASKER BASIC MEDICA L COMMENTARY RESEARCH AWARD A tale of two hormones Jeffrey M Friedman “Der Mensch denkt, Gott lenkt.” (“Man equivalent to a death sentence1. The only avail- Kleiner’s story had great personal resonance proposes, God disposes.”) able treatment was a starvation diet advocated for me. Here was another Jewish scientist, the —German proverb by Frederick Madison Allen, a physician work- grandson of immigrants, working a century ing at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical earlier at the same institution as me. But on A little more than a century ago, an arc of Research (now Rockefeller University) and the cusp of isolating the most important hor- research began that culminated in the identi- a leading authority on diabetes1–5. Allen was mone ever discovered, he walked away from it. fication of insulin by four scientists working the first to realize that diabetes was a general How did Kleiner come to study diabetes? Why in Toronto. With astonishing speed, this land- disorder of metabolism and that acidosis and did his studies cease so abruptly? Did Kleiner mark discovery became a life-saving treatment death could be forestalled if caloric intake was and his colleagues fully understand the impli- for thousands of people with diabetes around restricted. When acidosis developed, calories cations of his research? What was the personal the world. In time, insulin was established as were further reduced, and, for many, diabetes impact of his having missed the opportunity of the most important anabolic hormone and was a race between starvation and acidosis, the a lifetime? Kleiner’s work and career also raise found its place in the pantheon of medicine’s ultimate result of either condition often being a general question: what are the elements of a greatest discoveries.