The Origin, Spread, & Improvement of the Avocado, Sapodilla and Papaya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Avocado Production in Home Gardens Revised

AVOCADO PRODUCTION IN HOME GARDENS Author: Gary S. Bender, Ph.D. UCCE Farm Advisor Avocados are grown in home Soil Requirements gardens in the coastal zone of A fine sandy loam with good California from San Diego north drainage is necessary for long life to San Luis Obispo. Avocados and good health of the tree. It is (mostly Mexican varieties) can better to have deep soils, but also be grown in the Monterey – well-drained shallow soils are Watsonville region, in the San suitable if irrigation is frequent. Francisco bay area, and in the Clay soils, or shallow soils with “banana-belts” in the San Joaquin impermeable subsoils, should not Valley. Avocados are grown successfully in be planted to avocados. Mulching avocados frost-free inland valleys in San Diego County with a composted greenwaste (predominantly and western Riverside County, but attention chipped wood) is highly beneficial, but should be made to locating the avocado tree manures and mushroom composts are usually on the warmest microclimates on the too high in salts and ammonia and can lead to property. excessive root burn and “tip-burn” in the leaves. Manures should never be added to Climatic Requirements the soil back-fill when planting a tree. The Guatemalan races of avocado (includes varieties such as Nabal and Reed) are more Varieties frost-tender. The Hass variety (a Guatemalan/ The most popular variety in the coastal areas Mexican hybrid which is mostly Guatemalan) is Hass. The peel texture is pebbly, peel is also very frost tender; damage occurs to the color is at ripening, and it has excellent flavor fruit if the winter temperature remains at 30°F and peeling qualities. -

Moringa Oleifera 31.05.2005 8:55 Uhr Seite 1

Moringa oleifera 31.05.2005 8:55 Uhr Seite 1 Moringa oleifera III-4 Moringa oleifera LAM., 1785 syn.: Guilandina moringa LAM.; Hyperanthera moringa WILLD.; Moringa nux-ben PERR.; Moringa pterygosperma GAERTN., 1791 Meerrettichbaum, Pferderettichbaum Familie: Moringaceae Arabic: rawag Malayalam: murinna, sigru Assamese: saijna, sohjna Marathi: achajhada, shevgi Bengali: sajina Nepali: shobhanjan, sohijan Burmese: daintha, dandalonbin Oriya: sajina Chinese: la ken Portuguese: moringa, moringueiro English: drumstick tree, Punjabi: sainjna, soanjna horseradish tree, ben tree Sanskrit: shobhanjana, sigru French: moringe à graine ailée, Sinhalese: murunga morungue Spanish: ángela, ben, moringa Gujarati: midhosaragavo, saragavo Swahili: mrongo, mzunze Hindi: mungna, saijna, shajna Tamil: moringa, murungai Kannada: nugge Telegu: mulaga, munaga, Konkani: maissang, moring, tellamunaga moxing Urdu: sahajna Fig. 1: Flower detail (front and side view) Enzyklopädie der Holzgewächse – 40. Erg.Lfg. 6/05 1 Moringa oleifera 31.05.2005 8:55 Uhr Seite 2 Moringa oleifera III-4 Drumstick tree, also known as horseradish tree and ben It is cultivated and has become naturalized in other parts tree in English, is a small to medium-sized, evergreen or of Pakistan, India, and Nepal, as well as in Afghanistan, deciduous tree native to northern India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, West Asia, the Nepal. It is cultivated and has become naturalized well Arabian peninsula, East and West Africa, throughout the beyond its native range, including throughout South Asia, West Indies and southern Florida, in Central and South and in many countries of Southeast Asia, the Arabian Pe- America from Mexico to Peru, as well as in Brazil and ninsula, tropical Africa, Central America, the Caribbean Paraguay [17, 21, 29, 30, 51, 65]. -

Diversity and Distribution of Maize-Associated Totivirus Strains from Tanzania

Virus Genes (2019) 55:429–432 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11262-019-01650-6 Diversity and distribution of Maize-associated totivirus strains from Tanzania David Alan Read1 · Jonathan Featherston1 · David Jasper Gilbert Rees1 · Genevieve Dawn Thompson1 · Ronel Roberts2 · Bradley Charles Flett3 · Kingstone Mashingaidze3 · Gerhard Pietersen4 · Barnabas Kiula5 · Alois Kullaya6 · Ernest R. Mbega7 Received: 30 January 2019 / Accepted: 13 February 2019 / Published online: 21 February 2019 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Typically associated with fungal species, members of the viral family Totiviridae have recently been shown to be associated with plants, including important crop species, such as Carica papaya (papaya) and Zea mays (maize). Maize-associated totivirus (MATV) was first described in China and more recently in Ecuador, where it has been found to co-occur with other viruses known to elicit maize lethal necrosis disease (MLND). In a survey for maize-associated viruses, 35 samples were selected for Illumina HiSeq sequencing, from the Tanzanian maize producing regions of Mara, Arusha, Manyara, Kilimanjaro, Morogoro and Pwani. Libraries were prepared using an RNA-tag-seq methodology. Taxonomic classification of the result- ing datasets showed that 6 of the 35 samples from the regions of Arusha, Kilimanjaro, Morogoro and Mara, contained reads that were assigned to MATV reference sequences. This was confirmed with PCR and Sanger sequencing. Read assembly of the six MATV-associated datasets yielded partial MATV genomes, two of which were selected for further characterization, using RACE. This yielded two full-length MATV genomes, one of which is divergent from other available MATV genomes. -

The Latex-Fruit Syndrome: a Review on Clinical Features

Internet Symposium on Food Allergens 2(3):2000 http://www.food-allergens.de Review: The Latex-Fruit Syndrome: A Review on Clinical Features Carlos BLANCO Sección de Alergia, Hospital de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain SUMMARY KEYWORDS During the last decade, latex IgE-mediated allergy has been recognized as a very important medical problem. At the same time, many studies have dealt with allergic cross-reactions between aeroallergens and foods. Recently, a latex allergy "latex-fruit syndrome" has been postulated, because there is clear evidence of food allergy the existence of a significant clinical association between allergies to latex and cross-reactivity certain fruits. latex-fruit syndrome Several studies have demonstrated that from 20% to 60% of latex-allergic class I chitinases patients show IgE-mediated reactions to a wide variety of foods, mainly fruits. Although implicated foods vary among the studies, banana, avocado, chestnut and kiwi are the most frequently involved. Clinical manifestations of these reactions may vary from oral allergy syndrome to severe anaphylactic reactions, which are not uncommon, thus demonstrating the clinical relevance of this syndrome. The diagnosis of food hypersensitivities associated with latex allergy is based on the clinical history of immediate adverse reactions, suggestive of an IgE- mediated sensitivity. Prick by prick test with the fresh foods implicated in the reactions shows an 80% concordance with the clinical diagnosis, and therefore it seems to be the best diagnostic test currently available in order to confirm the suspicion of latex-fruit allergy. Once the diagnosis is achieved, a diet free of the offending fruits is mandatory. -

Safety Assessment of Carica Papaya (Papaya)-Derived Ingredients As Used in Cosmetics

Safety Assessment of Carica papaya (Papaya)-Derived Ingredients as Used in Cosmetics Status: Draft Report for Panel Review Release Date: February 21, 2020 Panel Meeting Date: March 16-17, 2020 The Cosmetic Ingredient Review Expert Panel members are: Chair, Wilma F. Bergfeld, M.D., F.A.C.P.; Donald V. Belsito, M.D.; Curtis D. Klaassen, Ph.D.; Daniel C. Liebler, Ph.D.; James G. Marks, Jr., M.D.; Lisa A. Peterson, Ph.D.; Ronald C. Shank, Ph.D.; Thomas J. Slaga, Ph.D.; and Paul W. Snyder, D.V.M., Ph.D. The CIR Executive Director is Bart Heldreth, Ph.D. This safety assessment was prepared by Alice Akinsulie, former Scientific Analyst/Writer and Priya Cherian, Scientific Analyst/Writer. © Cosmetic Ingredient Review 1620 L St NW, Suite 1200 ◊ Washington, DC 20036-4702 ◊ ph 202.331.0651 ◊fax 202.331.0088 ◊ [email protected] Distributed for Comment Only - Do Not Cite or Quote Commitment & Credibility since 1976 Memorandum To: CIR Expert Panel Members and Liaisons From: Priya Cherian, Scientific Analyst/Writer Date: February 21, 2020 Subject: Draft Report on Papaya-derived ingredients Enclosed is the Draft Report on 5 papaya-derived ingredients. The attached report (papaya032020rep) includes the following unpublished data that were received from the Council: 1) Use concentration data (papaya032020data1) 2) Manufacturing and impurities data on a Carica Papaya (Papaya) Fruit Extract (papaya032020data2) 3) Physical and chemical properties of a Carica Papaya (Papaya) Fruit Extract (papaya032020data3) Also included in this package for your review are the CIR report history (papaya032020hist), flow chart (papaya032020flow), literature search strategy (papaya032020strat), ingredient data profile (papaya032020prof), and updated 2020 FDA VCRP data (papaya032020fda). -

Propagation Experiments with Avocado, Mango, and Papaya

Proceedings of the AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR HORTICULTURAL SCIENCE 1933 30:382-386 Propagation Experiments with Avocado, Mango, and Papaya HAMILTON P. TRAUB and E. C. AUCHTER U. S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, D. C. During the past year several different investigations relative to the propagation of the avocado, mango and papaya have been conducted in Florida. In this preliminary report, the results of a few of the different experiments will be described. Germination media:—Avocado seeds of Gottfried (Mex.) during the summer season, and Shooter (Mex.) during the fall season; and Apple Mango seeds during the summer season, were germinated in 16 media contained in 4 x 18 x 24 cypress flats with drainage provided in the bottom. The eight basic materials and eight mixtures of these, in equal proportions in each case, tested were: 10-mesh charcoal, 6-mesh charcoal, pine sawdust, cypress sawdust, sand, fine sandy loam, carex peat, sphagnum peat, sand plus loam, carex peat plus sand, sphagnum peat plus sand, carex peat plus loam, sand plus coarse charcoal, loam plus coarse charcoal, cypress sawdust plus coarse charcoal, and carex peat plus sand plus coarse charcoal. During the rainy summer season, with relatively high temperature and an excess of moisture without watering, 10-mesh charcoal, and the mixture of carex peat plus sand plus charcoal proved most rapid, but for the drier, cooler fall season, when watering was necessary, the mixture of cypress sawdust plus charcoal was added to the list. During the rainy season the two charcoal media, sphagnum peat, sand plus charcoal, cypress sawdust plus charcoal, and carex peat plus sand plus charcoal gave the highest percentages of germination at the end of 6 to 7 weeks, but during the drier season the first three were displaced by carex peat plus sand, and sphagnum peat plus sand. -

Chapter 1 Definitions and Classifications for Fruit and Vegetables

Chapter 1 Definitions and classifications for fruit and vegetables In the broadest sense, the botani- Botanical and culinary cal term vegetable refers to any plant, definitions edible or not, including trees, bushes, vines and vascular plants, and Botanical definitions distinguishes plant material from ani- Broadly, the botanical term fruit refers mal material and from inorganic to the mature ovary of a plant, matter. There are two slightly different including its seeds, covering and botanical definitions for the term any closely connected tissue, without vegetable as it relates to food. any consideration of whether these According to one, a vegetable is a are edible. As related to food, the plant cultivated for its edible part(s); IT botanical term fruit refers to the edible M according to the other, a vegetable is part of a plant that consists of the the edible part(s) of a plant, such as seeds and surrounding tissues. This the stems and stalk (celery), root includes fleshy fruits (such as blue- (carrot), tuber (potato), bulb (onion), berries, cantaloupe, poach, pumpkin, leaves (spinach, lettuce), flower (globe tomato) and dry fruits, where the artichoke), fruit (apple, cucumber, ripened ovary wall becomes papery, pumpkin, strawberries, tomato) or leathery, or woody as with cereal seeds (beans, peas). The latter grains, pulses (mature beans and definition includes fruits as a subset of peas) and nuts. vegetables. Definition of fruit and vegetables applicable in epidemiological studies, Fruit and vegetables Edible plant foods excluding -

Annona Cherimola Mill.) and Highland Papayas (Vasconcellea Spp.) in Ecuador

Faculteit Landbouwkundige en Toegepaste Biologische Wetenschappen Academiejaar 2001 – 2002 DISTRIBUTION AND POTENTIAL OF CHERIMOYA (ANNONA CHERIMOLA MILL.) AND HIGHLAND PAPAYAS (VASCONCELLEA SPP.) IN ECUADOR VERSPREIDING EN POTENTIEEL VAN CHERIMOYA (ANNONA CHERIMOLA MILL.) EN HOOGLANDPAPAJA’S (VASCONCELLEA SPP.) IN ECUADOR ir. Xavier SCHELDEMAN Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor (Ph.D.) in Applied Biological Sciences Proefschrift voorgedragen tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de Toegepaste Biologische Wetenschappen Op gezag van Rector: Prof. dr. A. DE LEENHEER Decaan: Promotor: Prof. dr. ir. O. VAN CLEEMPUT Prof. dr. ir. P. VAN DAMME The author and the promotor give authorisation to consult and to copy parts of this work for personal use only. Any other use is limited by Laws of Copyright. Permission to reproduce any material contained in this work should be obtained from the author. De auteur en de promotor geven de toelating dit doctoraatswerk voor consultatie beschikbaar te stellen en delen ervan te kopiëren voor persoonlijk gebruik. Elk ander gebruik valt onder de beperkingen van het auteursrecht, in het bijzonder met betrekking tot de verplichting uitdrukkelijk de bron vermelden bij het aanhalen van de resultaten uit dit werk. Prof. dr. ir. P. Van Damme X. Scheldeman Promotor Author Faculty of Agricultural and Applied Biological Sciences Department Plant Production Laboratory of Tropical and Subtropical Agronomy and Ethnobotany Coupure links 653 B-9000 Ghent Belgium Acknowledgements __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Acknowledgements After two years of reading, data processing, writing and correcting, this Ph.D. thesis is finally born. Like Veerle’s pregnancy of our two children, born during this same period, it had its hard moments relieved luckily enough with pleasant ones. -

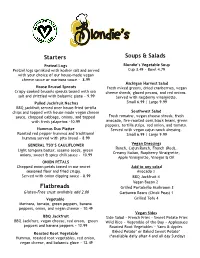

Starters Flatbreads Soups & Salads

Starters Soups & Salads Pretzel Logs Blondie’s Vegetable Soup Pretzel logs sprinkled with kosher salt and served Cup 3.49 ~ Bowl 4.79 with your choice of our house-made vegan cheese sauce or marinara sauce ~ 8.99 Michigan Harvest Salad House Brussel Sprouts Fresh mixed greens, dried cranberries, vegan Crispy cooked brussels sprouts tossed with sea cheese shreds, glazed pecans, and red onions. salt and drizzled with balsamic glaze ~ 9.99 Served with raspberry vinaigrette. Pulled Jackfruit Nachos Small 6.99 | Large 9.99 BBQ jackfruit served over house-fried tortilla chips and topped with house-made vegan cheese Southwest Salad sauce, chopped cabbage, onions, and topped Fresh romaine, vegan cheese shreds, fresh with fresh jalapeños ~10.99 avocado, fire-roasted corn,black beans, green peppers, tortilla strips, red onion, and tomato. Hummus Duo Platter Served with vegan cajun ranch dressing. Roasted red pepper hummus and traditional Small 6.99 | Large 9.99 hummus served with pita bread ~ 8.99 GENERAL TSO’S CAULIFLOWER Vegan Dressings Ranch, Cajun Ranch, French (Red), Light tempura batter, sesame seeds, green Creamy Italian, Raspberry Vinaigrette, onions, sweet & spicy chili sauce – 10.99 Apple Vinaigrette, Vinegar & Oil ONION PETALS Chopped onion petals tossed in our secret Add to any salad seasoned flour and fried crispy. Avocado 2 Served with onion dipping sauce – 8.99 BBQ Jackfruit 4 Vegan Bacon 2 Flatbreads Grilled Portobello Mushroom 3 Gluten-Free crust available add 2.00 Garbanzo Beans (Chick Peas) 1 Vegetable Grilled Tofu 4 Marinara, -

Marker-Assisted Breeding for Papaya Ringspot Virus Resistance in Carica Papaya L

Marker-Assisted Breeding for Papaya Ringspot Virus Resistance in Carica papaya L. Author O'Brien, Christopher Published 2010 Thesis Type Thesis (Masters) School Griffith School of Environment DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3639 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/365618 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Marker-Assisted Breeding for Papaya Ringspot Virus Resistance in Carica papaya L. Christopher O'Brien BAppliedSc (Environmental and Production Horticulture) University of Queensland Griffith School of Environment Science, Environment, Engineering and Technology Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy September 4, 2009 2 Table of Contents Page No. Abstract ……………………………………………………… 11 Statement of Originality ………………………………………........ 13 Acknowledgements …………………………………………. 15 Chapter 1 Literature review ………………………………....... 17 1.1 Overview of Carica papaya L. (papaya)………………… 19 1.1.1 Taxonomy ………………………………………………… . 19 1.1.2 Origin ………………………………………………….. 19 1.1.3 Botany …………………………………………………… 20 1.1.4 Importance …………………………………………………... 25 1.2 Overview of Vasconcellea species ……………………… 28 1.2.1 Taxonomy …………………………………………………… 28 1.2.2 Origin ……………………………………………………… 28 1.2.3 Botany ……………………………………………………… 31 1.2.4 Importance …………………………………………………… 31 1.2.5 Brief synopsis of Vasconcellea species …………………….. 33 1.3 Papaya ringspot virus (PRSV-P)…………………………. 42 1.3.1 Overview ………………………………………………………. 42 1.3.2 Distribution …………………………………………………… 43 1.3.3 Symptoms and effects ……………………………………….. .. 44 1.3.4 Transmission …………………………………………………. 45 1.3.5 Control ………………………………………………………. .. 46 1.4 Breeding ………………………………………………………. 47 1.4.1 Disease resistance …………………………………………….. 47 1.4.2 Biotechnology………………………………………………….. 50 1.4.3 Intergeneric hybridisation…………………………………….. 51 1.4.4 Genetic transformation………………………………………… 54 1.4.5 DNA analysis ………………………………………………..... -

Avocado Production in California Patricia Lazicki, Daniel Geisseler and William R

Avocado Production in California Patricia Lazicki, Daniel Geisseler and William R. Horwath Background Avocados are native to Central America and the West Indies. While the Spanish were familiar with avocados, they did not include them in the mission gardens. The first recorded avocado tree in California was planted in 1856 by Thomas White of San Gabriel. The first commercial orchard was planted in 1908. In 1913 the variety ‘Fuerte’ was introduced. This became the first important commercial variety, due to its good taste and cold tolerance. Despite its short season and Figure 1: Area of bearing avocado trees in California since erratic bearing it remained the industry 1925 [4,5]. standard for several decades [3]. The black- skinned ‘Hass’ avocado was selected from a seedling grown by Robert Hass of La Habra in 1926. ‘Hass’ was a better bearer and had a longer season, but was initially rejected by consumers already familiar with the green-skinned ‘Fuerte’. However, by 1972 ‘Hass’ surpassed ‘Fuerte’ as the dominant variety, and as of 2012 accounted for about 95% of avocados grown in California [3]. By the early 1930s, California had begun to export avocados to Europe. Figure 2: California avocado production (total crop and Research into avocados’ nutritional total value) since 1925 [4,5]. benefits in the 1940s — and a shortage of [1,3] fats and oils created by World War II — in the early 1990s . The state’s crop lost over [5] contributed to an increased acceptance of the half its value between 1990 and 1993 (Fig. 2) . fruit [3]. However, acreage expansion from 1949 Aggressive marketing, combined with acreage to 1965 depressed markets and led to slightly reduction, revived the industry for the next [1,3] decreased plantings through the 1960s (Fig. -

(Carica Papaya L.) Biology and Biotechnology

Tree and Forestry Science and Biotechnology ©2007 Global Science Books Papaya (Carica papaya L.) Biology and Biotechnology Jaime A. Teixeira da Silva1* • Zinia Rashid1 • Duong Tan Nhut2 • Dharini Sivakumar3 • Abed Gera4 • Manoel Teixeira Souza Jr.5 • Paula F. Tennant6 1 Kagawa University, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Horticulture, Ikenobe, 2393, Miki-cho, Kagawa, 761-0795, Japan 2 Plant Biotechnology Department, Dalat Institute of Biology, 116 Xo Viet Nghe Tinh, Dalat, Lamdong, Vietnam 3 University of Pretoria, Postharvest Technology Group, Department of Microbiology and Plant Pathology, Pretoria, 0002, South Africa 4 Department of Virology, Agricultural Research Organization, The Volcani Center, Bet Dagan 50250, Israel 5 Embrapa LABEX Europa, Plant Research International (PRI), Wageningen University & Research Centre (WUR), Wageningen, The Netherlands 6 Department of Life Sciences, University of the West Indies, Mona, Kingston 7, Jamaica Corresponding author : * [email protected] ABSTRACT Papaya (Carica papaya L.) is a popular and economically important fruit tree of tropical and subtropical countries. The fruit is consumed world-wide as fresh fruit and as a vegetable or used as processed products. This review focuses primarily on two aspects. Firstly, on advances in in vitro methods of propagation, including tissue culture and micropropagation, and secondly on how these advances have facilitated improvements in papaya genetic transformation. An account of the dietary and nutritional composition of papaya, how these vary with culture methods, and secondary metabolites, both beneficial and harmful, and those having medicinal applications, are dis- cussed. An overview of papaya post-harvest is provided, while ‘synseed’ technology and cryopreservation are also covered. This is the first comprehensive review on papaya that attempts to integrate so many aspects of this economically and culturally important fruit tree that should prove valuable for professionals involved in both research and commerce.