High Value Products, Supermarkets and Vertical Arrangements in Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pipanniversarybrochure.Pdf

www.jardines.com “ Pride in Performance has enabled us to share and celebrate successes across the Group. Anthony Nightingale ” CONTENTS 2 A Decade of Pride in Performance 3 How it Works 5 5 elements to Success 6 Striving 12 Innovating 20 Collaborating 26 Solving 34 Connecting 45 The Entries A DECADE OF PRIDE IN PERFORMANCE HOW IT WORKs A myriad of achievements have contributed to Jardine Matheson’s success since its From inception, the chief executive officers of each business gave their support and founding in 1832. The content of this booklet, however, considers the Group’s more recent encouragement to the new award programme, getting PIP off to an excellent start. history, and a formalized approach that was launched in 2002 to identify and reward outstanding performances across the Group. In the first three years of PIP, entrants sought recognition as the Grand Prize Winner or one of two runners up. From 2005, five categories were introduced so as to recognize specific Through the Pride in Performance (‘PIP’) annual award programme, Jardines recognizes areas of achievement, from which the Grand Prize Winner is then chosen. individual business units within the Group that embody its core values and translate them into sustained commercial success. In addition to recognition, PIP is designed to share Of the categories, some remained consistent, such as Customer Focus, Marketing those operating company success stories with the larger Group. Excellence and Successful New Venture, while others evolved. Business Turnaround became Business Outperformance as the Group’s operations progressed, and Productivity Using the Group’s core values as criteria for submission – The Right People, Energy, Enhancement evolved into Innovation and Creativity. -

Annual Report 2019 Our Goal: “ to Give Our Customers Across Asia a Store They TRUST, Delivering QUALITY, SERVICE and VALUE.”

Annual Report 2019 Our Goal: “ To give our customers across Asia a store they TRUST, delivering QUALITY, SERVICE and VALUE.” Dairy Farm International Holdings Limited is incorporated in Bermuda and has a standard listing on the London Stock Exchange, with secondary listings in Bermuda and Singapore. The Group’s businesses are managed from Hong Kong by Dairy Farm Management Services Limited through its regional offices. Dairy Farm is a member of the Jardine Matheson Group. A member of the Jardine Matheson Group Annual Report 2019 1 Contents 2 Corporate Information 36 Financial Review 3 Dairy Farm At-a-Glance 39 Directors’ Profiles 4 Highlights 41 Our Leadership 6 Chairman’s Statement 44 Financial Statements 10 Group Chief Executive’s Review 116 Independent Auditors’ Report 14 Sustainable Transformation at Dairy Farm 124 Five Year Summary 18 Business Review 125 Responsibility Statement 18 Food 126 Corporate Governance 22 Health and Beauty 133 Principal Risks and Uncertainties 26 Home Furnishings 135 Shareholder Information 30 Restaurants 136 Retail Outlets Summary 34 Other Associates 137 Management and Offices 2 Dairy Farm International Holdings Limited Corporate Information Directors Dairy Farm Management Services Limited Ben Keswick Chairman and Managing Director Ian McLeod Directors Group Chief Executive Ben Keswick Clem Constantine Chairman (joined the Board on 11th November 2019) Ian McLeod Neil Galloway Group Chief Executive (stepped down on 31st March 2019) Clem Constantine Mark Greenberg Chief Financial Officer (joined the board on 19th November 2019) George J. Ho Neil Galloway Adam Keswick Group Finance & IKEA Director (stepped down on 31st March 2019) Simon Keswick (stepped down on 1st January 2020) Choo Peng Chee Chief Executive Officer – North Asia Michael Kok & Group Convenience (stepped down on 8th May 2019) Sam Kim Dr Delman Lee Chief Executive Officer – Health & Beauty and Chief Marketing & Business Development Officer Anthony Nightingale Martin Lindström Y.K. -

Dairy Farm International Holdings Limited

Annual ReportAnnual 2017 Dairy Farm International Holdings Limited Annual Report 2017 Our Goal : “To give our customers across Asia a store they TRUST, delivering QUALITY, SERVICE and VALUE” Dairy Farm International Holdings Limited is incorporated in Bermuda and has a standard listing on the London Stock Exchange, with secondary listings in Bermuda and Singapore. The Group’s businesses are managed from Hong Kong by Dairy Farm Management Services Limited through its regional offices. Dairy Farm is a member of the Jardine Matheson Group. A member of the Jardine Matheson Group Contents 2 Corporate Information 3 Dairy Farm At-a-Glance 4 Highlights 6 Chairman’s Statement 8 Group Chief Executive’s Review 12 Feature Stories 16 Business Review 16 Food 22 Health and Beauty 26 Home Furnishings 30 Restaurants 34 Financial Review 37 Directors’ Profiles 39 Our Leadership 42 Financial Statements 100 Independent Auditors’ Report 108 Five Year Summary 109 Responsibility Statement 110 Corporate Governance 117 Principal Risks and Uncertainties 119 Shareholder Information 120 Retail Outlets Summary 121 Management and Offices Annual Report 2017 1 Corporate Information Directors Dairy Farm Management Services Limited Ben Keswick Chairman and Managing Director Ian McLeod Directors Group Chief Executive Ben Keswick Neil Galloway Chairman Mark Greenberg Ian McLeod Group Chief Executive George J. Ho Neil Galloway Adam Keswick Group Finance Director Sir Henry Keswick Choo Peng Chee Regional Director, North Asia (Food) Simon Keswick Gordon Farquhar Michael Kok Group Director, Health and Beauty Dr George C.G. Koo Martin Lindström Group Director, IKEA Anthony Nightingale Michael Wu Y.K. Pang Chairman and Managing Director, Maxim’s Jeremy Parr Mark Greenberg Lord Sassoon, Kt Y.K. -

Press Release Ahold to Divest Its Indonesian Operation to Hero

Press Release Royal Ahold Public Relations Date: April 29, 2003 For more information: +31 75 659 57 20 Ahold to divest its Indonesian operation to Hero Zaandam, The Netherlands, April 29, 2003 – Ahold hereby announces that it has reached agreement for the sale of its Indonesian operation to PT Hero Supermarket Tbk for approximately Euro 12 million, excluding proceeds from the sale of store inventory. This asset purchase agreement is subject to the approval of Hero’s shareholders and is expected to be finalized in the third quarter of 2003. Hero is a prominent food retail group listed on the Jakarta stock exchange with 200 outlets throughout Indonesia. The transaction involves 22 stores plus one under construction, and two distribution centers. The actual transfer of the stores and both distribution centers will take place following the approval of Hero shareholders. Staff at Ahold’s Indonesian headquarters are not included in the transaction, although Ahold is committed to meeting its obligations to these associates. The divestment of Ahold’s activities in Indonesia is part of the company’s strategic plan to restructure its portfolio to focus on high-performing businesses, to concentrate on its mature and most stable markets and to reduce its debt. Ahold first entered the Indonesian market through a technical service agreement with the PSP group in 1996. That agreement ended in 2002 and Ahold Tops Indonesia became a wholly-owned subsidiary. Unaudited net sales in 2002 amounted to approximately Euro 37 million. Ahold employs approximately 1,600 people in Indonesia. Ahold Corporate Communications: +31.75.659.5720 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Certain statements in this press release are “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of U.S. -

Overseas Packaging Study Tour VAMP.006 1996

Overseas packaging study tour VAMP.006 1996 Prepared by: B. Lee ISBN: 1 74036 973 4 Published: June 1996 © 1998 This publication is published by Meat & Livestock Australia Limited ABN 39 081 678 364 (MLA). Where possible, care is taken to ensure the accuracy of information in the publication. Reproduction in whole or in part of this publication is prohibited without the prior written consent of MLA. MEAT & LIVESTOCK AUSTRALIA CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................ 1 2.0 BACKGROUND .................................................... 4 3.0 THE INTERNATIONAL STUDY TOUR .............. .................. 6 3.1 Objectives of the International Study Tour ................................. 6 3.2 Study Tour Itinerary and Dates .......................................... 6 3.3 The Study Team ...................................................... 6 4.0 SUMMARY OF SITE VISITS ......................................... 7 4.1 Taiwan ............................................................. 7 4.2 Hong Kong .......................................................... 8 4.3 France .............................................................. 9 4.4 Holland ............................................................ l 0 4.5 United Kingdom ..................................................... 13 4.6 Canada ............................................................ 15 4.7 Summary Comments of Site Visits by Study Group ......................... 17 5.0 KEY FINDINGS FROM THE STUDY TOUR ....... .................... 18 5.1 -

Matahari Putra Prima (MPPA IJ)

Indonesia Initiating Coverage 6 July 2021 Consumer Non-cyclical | Retail - Staples Matahari Putra Prima (MPPA IJ) Buy The Rising Phoenix; Initiate BUY Target Price (Return): IDR1,750 (+50%) Price: IDR1,170 Market Cap: USD606m Avg Daily Turnover (IDR/USD) 81,591m/5.66m Initiate coverage with a BUY and IDR1,750 TP, 50% upside. Matahari Putra Analysts Prima’s recent revamping of initiatives should help to transform its business and keep it ahead of competitors. A strong focus on digital initiatives – particularly Indonesia Research Team the collaboration with Indonesia’s largest technology group GoTo – will likely +6221 5093 9888 lead to greater monetisation from the e-groceries trend. Our SOP-based TP is [email protected] derived from 1.7x 2023F P/S (fresh products) and 11.0x 2023F EV/BITDA (non- fresh products). Possible additional investment from GoTo is a likely catalyst to its share price. Michael Setjoadi Internal business transformation on the cards. The company aims to strongly +6221 5093 9844 [email protected] focus on expanding sales of its fresh products. We are positive on this strategy given less intense competition in the segment and this strategy may work well, supported by its strong merchandising programme (ie partnership with Disney), Marco Antonius Indonesian Ulama Council’s (MUI) halal assurance system (HAS) and strong +6221 5093 9849 logistics facilities. The company will also continue its expansion with a new, [email protected] smaller efficient yet modern hypermarket format, yielding better productivity and efficiency. This should help MPPA penetrate into residential areas, as well as Tier II and III cities. -

Studying Landslide Displacements in Megamendung (Indonesia) Using GPS Survey Method

PROC. ITB Eng. Science Vol. 36 B, No. 2, 2004, 109-123 109 Studying Landslide Displacements in Megamendung (Indonesia) Using GPS Survey Method Hasanuddin Z. Abidin 1, H. Andreas 1, M. Gamal 1, Surono 2 & M. Hendrasto 2 1 Department of Geodetic Engineering, Institute of Technology Bandung, Jl. Ganesa 10, Bandung, Indonesia, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Directorate of Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation, Jl. Diponegoro 57, Bandung 40132 Abstract. Landslide is one of prominent geohazards that frequently affects Indonesia, especially in the rainy season. It destroys not only environment and property, but usually also causes deaths. Landslide monitoring is therefore very crucial and should be continuously done. One of the methods that can have a contribution in studying landslide phenomena is repeated GPS survey method. This paper presents and discusses the operational performances, constraints and results of GPS surveys conducted in a well known landslide prone area in West Java (Indonesia), namely Megamendung, the hilly region close to Bogor. Three GPS surveys involving 8 GPS points have been conducted, namely on April 2002, May 2003 and May 2004, respectively. The estimated landslide displacements in the area are relatively quite large in the level of a few dm to a few m. Displacements up to about 2-3 m were detected in the April 2002 to May 2003 period, and up to about 3-4 dm in the May 2003 to May 2004 period. In both periods, landslides in general show the northwest direction of displacements. Displacements vary both spatially and temporally. This study also suggested that in order to conclude the existence of real and significant displacements of GPS points, the GPS estimated displacements should be subjected to three types of testing namely: the congruency test on spatial displacements, testing on the agreement between the horizontal distance changes with the predicted direction of landslide displacement, and testing on the consistency of displacement directions on two consecutive periods. -

Chytridiomycosis in Frogs of Mount Gede Pangrango, Indonesia

Vol. 82: 187–194, 2008 DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Published December 22 doi: 10.3354/dao01981 Dis Aquat Org Chytridiomycosis in frogs of Mount Gede Pangrango, Indonesia M. D. Kusrini1,*, L. F. Skerratt2, S. Garland3, L. Berger2, W. Endarwin1 1Departemen Konservasi Sumberdaya Hutan dan Ekowisata, Fakultas Kehutanan, Institut Pertanian Bogor, Kampus Darmaga, PO Box 168, Bogor 1600, Indonesia 2Amphibian Disease Ecology Group, School of Public Health, Tropical Medicine and Rehabilitation Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville 4811, Australia 3Amphibian Disease Ecology Group, School of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville 4811, Australia ABSTRACT: Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) is a fungus recognised as one of the causes of global amphibian population declines. To assess its occurrence, we conducted PCR diagnostic assays of 147 swab samples, from 13 species of frogs from Mount Gede Pangrango National Park, Indonesia. Four swab samples, from Rhacophorus javanus, Rana chalconota, Leptobrachium hasseltii and Lim- nonectes microdiscus, were positive for Bd and had low to moderate levels of infection. The sample from L. hasseltii was from a tadpole with mouthpart deformities and infection was confirmed by his- tology and immunohistochemistry. An additional sample from Leptophryne cruentata showed a very low level of infection (≤1 zoospore equivalent). This is the first record of Bd in Indonesia and in South- east Asia, dramatically extending the global distribution of Bd, with important consequences for international amphibian disease control, conservation and trade. Consistent with declines in amphib- ian populations caused by Bd in other parts of the world, evidence exists for the decline and possible extirpation of amphibian populations at high elevations and some decline with recovery of popula- tions at lower elevations on this mountain. -

200 Leading Retailers in Asia

200 Leading Retailers in Asia . Showcasing the very best in retail innovation across Asia from hypermarkets to convenience retail made with Introduction Thank you for downloading this eBook featuring 200 of the most exciting & innovative retailers in Asia. We've spent weeks speaking with our community and researching across the web to bring you this list, and we hope that you nd it useful & interesting. This is by no means a denitive resource, but more an opportunity to spark a discussion. Which retailers would make your top 200? Which countries do you see as the biggest opportunity for retail? Which categories excite you the most? How will this list change as e-commerce continues to grow? We'd love to hear your thoughts. Seamless Asia We were inspired to put this list together ahead of our Seamless Asia conference and exhibition, running on 2nd-4th May 2018 at Suntec Convention Centre here in Singapore. Over the years we've seen so many phenomenal retailers take the stage to present their challenges and their visions for the future of retail. Through this eBook we wanted to honour many of those businesses, as well as showcase some of those who we hope will join us in the future to share their stories. We would love to see you and your team at the show in May, as we come together to celebrate the very best in Asian retail, and look ahead to the seamless future of commerce throughout the region. Best wishes Oliver Arscott & Team Seamless Key Statistics Category Statistics First let's take a look at categories. -

Profil Perusahaan Company Profile

04 Profil Perusahaan Company Profile PT Hero Supermarket Tbk 32 33 Laporan Tahunan 2019 | Annual Report 2019 Ikhtisar Kinerja 2019 Informasi Saham Laporan Manajemen Profil Perusahaan 2019 Performance Overview Stock Information Management Reports Company Profile Identitas Perusahaan Company Identity Nama Perusahaan Company Name Situs Resmi Perusahaan Company Official Sites PT Hero Supermarket Tbk www.hero.co.id www.herosupermarket.co.id www.guardianindonesia.co.id Perubahan Nama Perusahaan Change of Company www.giant.co.id Sebelumnya Perseroan bernama PT Hero Mini www.IKEA.co.id Supermarket, kemudian berganti nama menjadi PT Hero Supermarket per Rapat Umum Facebook Pemegang Saham tanggal 7 Juni 1991. Hero Infoodtainment, Previously named PT Hero Mini Supermarket, Guardian Indonesia, the Company changed its name to PT Hero Giant Indonesia Supermarket as of the General Meeting of IKEA Indonesia Shareholders dated 7 June 1991 Hero Peduli Twitter Alamat Kantor Pusat Head Office Address Herosupermarket Graha Hero, CBD Bintaro Sektor 7 Blok B7/ GuardianID A7 Pondok Jaya, Pondok Aren, Tangerang GiantIndo Selatan, 15224, Indonesia. IKEA_Ind Graha Hero, CBD Bintaro Sektor 7 Blok B7/A7 Pondok Jaya, Pondok Aren, Tangerang Selatan, Instagram 15224, Indonesia Herosupermarket giant_indonesia Alamat Kontak Contact Address guardianindonesia Sekretaris Perusahaan, Graha HERO Lantai 4, IKEA_id CBD Bintaro Sektor 7 Blok B7 / A7, Pondok hero.peduli Aren, Tangerang Selatan, 15224, Indonesia Corporate Secretary, Graha HERO 4th Floor, Tanggal Pendirian Date of -

Sustainable Culinary Tourism in Puncak, Bogor

I. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Tourism industry is one of the largest industries in Indonesia, it contributed 153.25 trillion rupiahs or 3.09% of the total bruto domestic product of Indonesia in 2010 (Ministry of Culture and Tourism of Indonesia, 2011). It was also one of the significant national economic resources. Tourist arrival to Indonesia in 2011 reached 7.7 million people, increased from 7 million people in 2010. This was, so far, the third largest industry in Indonesia after oil and gas industry and palm oil industry. Culinary has become a secondary or even primary reason that adds value to tourism. Consuming food products is the most enjoyable activity during tour session. And the interesting fact is that, budget for this activity is the last thing tourist would like to cut off (Pyo et al, 1991). A research from Teffler & Wall (1996) also found that consumption could consume up to one-third of the budget for travelling. These tell us that consumption by tourist will give significant contribution to local restaurant, food industry, and in the end, accelerate economic growth of destination region. Culinary tourism, which embedded into food service provision, is a vital support for the tourism industry. The food processed in culinary tourism may origin from local farmer, or imported. Local resource imply employment of native farmer, while imported food means loss of devise, and missing chance of local product development. Furthermore, this may diminish the income for local farmer and cattle. 1 Henderson (2004) had investigated tourists’ behavior in deciding what kind of food they prefer while touring to Singapore. -

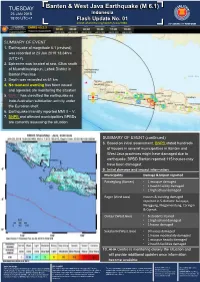

Banten & West Java Earthquake

TUESDAY Banten & West Java Earthquake (M 6.1) 23 JAN 2018 Indonesia 18:00 UTC+7 Flash Update No. 01 adinet.ahacentre.org/reports/view/1048 SUMMARY OF EVENT 1. Earthquake of magnitude 6.1 (revised) was recorded at 23 Jan 2018 13:34hrs (UTC+7). 2. Epicentre was located at sea, 43km south of Muarabinuangeun, Lebak District in Banten Province 3. Depth was recorded as 61 km 4. No tsunami warning has been issued and agencies are monitoring the situation 5. BMKG has classified the earthquake as Indo-Australian subduction activity under the Eurasian shelf. 6. Earthquake intensity reported MMI II – V. 7. BNPB and affected municipalities BPBDs are currently assessing the situation. SUMMARY OF EVENT (continued) 8. Based on initial assessment, BNPB stated hundreds of houses in several municipalities in Banten and West Java provinces might have damaged due to earthquake. BPBD Banten reported 115 houses may have been damaged. 9. Initial damage and impact information: Municipality Damage & Impact reported Pandeglang (Banten) • 1 mosque damaged • 1 health facility damaged • 1 high school damaged Bogor (West Java) Houses & building damaged reported in 5 districts: Sukajaya, Nanggung, Megamendung, Caringin & Cijeruk. Cianjur (West Java) • 6 students injured • 1 high school damaged • 1 house damaged Sukabumi (West Java) • 9 houses damaged • 1 house moderately damaged • 1 mosque heavily damaged • 2 health facilities damaged 10. AHA Centre is monitoring closely the situation and will provide additional updates once information become available. DATA SOURCES DISCLAIMER © 2018 AHA Centre. Our mailing address is: AHA Centre Disaster Monitoring & Response System (DMRS); The AHA Centre was established in November 2011 by the The use of boundaries, geographic names, related information All rights reserved.