Why Neo-Paganism?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CERN Pt. 6 Cernunnos.Wps

CERNunnos resurrected for CERN In CERN pt. 4 we learned about the tomb of a Celtic Prince in France. What was unearthed was the river deity Acheloos. Cernunnos is yet another horned deity. He is also a hunter like Nimrod. “ Cernunnos is the conventional name given in Celtic studies to depictions of the "horned god" (sometimes referred to as Hern the Hunter) of Celtic polytheism. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cernunnos Cernunnos: He is depicted with rings on his horns due to the association with torcs. This horned god is associated with rings. “often seated cross-legged and often associated with animals and holding or wearing torcs” What we see with Cernunnos is an allusion to CERN not only within his name, but also his association with rings. A typical torc: In the name Cernunnos we see the anagram “No Sun Cern”. I would say this refers to the fact that the Antichrist is NOT the authentic Sun or Son of God. What we also see is “Nu Son CERN“ and this relates to the “Nu 8 man” discussed in CERN pt. 2, the Shiva monkey god Hanuman! Interesting coincidence. The theme of a two horned deity is ancient and can be seen in many cultures. Pan: The Roman deity Faunus: And don’t forget this one! The two horned theme is associated with Shiva as Shiva Pashupati and thus ties in with CERNunnos as yet another horned deity. The horned deity Shiva whose image is located at CERN is most likely due to the affiliation with masculine/feminine seen with Shiva/Shakti. -

Beltane 2013

Pooka’s Page for Grownups This issue of Pooka Pages has been, without a doubt, the hardest for me to produce in the entire eleven years since it was begun. Indeed, for a short while I wasn’t sure there would ever be another issue. As many of you may have heard, Pooka crossed over to the Summerlands on March 25 th. I’m devastated without my little partner, co-author and familiar at my side. But the sympathy and support of friends helped me through those first mind- numbing days and our Pooka Pages Team members gallantly rallied through our shared grief to make sure this issue did get to you. Even Pooka, himself, took part. His little ghost sat pressed against my side and dictated a story about his Great Adventure. He wanted the children to know, as we did, that this was a Transition, that he’s resting comfortably with the God & Goddess for a while and that he will be back. That someday, I will look into the eyes of a little black kitten and say: “There you are! I found you! ” When that day comes, Pooka (in his new body) and I, together, will write Part Two of his “Great Adventure”… Until then, his indomitable little spirit lives on… and so will the Pooka Pages. Some Other Names: May Day, Roodemas, Walpurgis (Germany), Cetshamain (Ireland), Cyntefin (Wales), Cala Me' (Cornwall) and Kala-Hanv (Brittany) This is when the Goddess and the God get married and all of Nature celebrates with them. The ancient Celts divided the year into two parts – Winter, the colder, dark part that began at Samhain, and Summer, the lighter, warmer part, which officially started at Beltane. -

Celtic Mythology Ebook

CELTIC MYTHOLOGY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Arnott MacCulloch | 288 pages | 16 Nov 2004 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486436562 | English | New York, United States Celtic Mythology PDF Book It's amazing the similarities. In has even influenced a number of movies, video games, and modern stories such as the Lord of the Rings saga by J. Accept Read More. Please do not copy anything without permission. Vocational Training. Thus the Celtic goddess, often portrayed as a beautiful and mature woman, was associated with nature and the spiritual essence of nature, while also representing the contrasting yet cyclic aspects of prosperity, wisdom, death, and regeneration. Yours divine voice Whispers the poetry of magic that flow through the wind, Like sweet-tasting water of the Boyne. Some of the essential female deities are Morrigan , Badb , and Nemain the three war goddess who appeared as ravens during battles. The Gods told us to do it. Thus over time, Belenus was also associated with the healing and regenerative aspects of Apollo , with healing shrines dedicated to the dual entities found across western Europe, including the one at Sainte-Sabine in Burgundy and even others as far away as Inveresk in Scotland. In most ancient mythical narratives, we rarely come across divine entities that are solely associated with language. Most of the records were taken around the 11 th century. In any case, Aengus turned out to be a lively man with a charming if somewhat whimsical character who always had four birds hovering and chirping around his head. They were a pagan people, who did not believe in written language. -

LUGHNASADH 2017 Welcome to the Lughnasadh 2017 Issue of Serpentstar!

A newsletter of The Order of Bards Ovates and Druids in the Southern Hemisphere LUGHNASADH 2017 Welcome to the Lughnasadh 2017 issue of SerpentStar! Once again we move into a new calendar year, and begin the revelries of harvest time. Macadamia Grove had the joy of playing with fire for a second time, pictures on this page and elsewhere. Lots of neat stuff for you in this issue - poetry from wyverne and Chris Parker, Part 2 of James Howell's thought- provoking (and very topical) article, William Rattley shares another musing with us, we welcome the Song of the Eastern Sea Seed Group to the group listings, OBOD's new Portuguese language magazine Ophiusa to the publications list, two new celebrants (Jenneth Graham and Pamela Meekings-Stewart) to our advert section, and there's info on the 2017 Assembly which will be held in Sydney in August. And if that's not enough, we debut a bursting new New Zealand section - 'Aotearoa'! It's my hope that the marvellous content offered by our NZ cousins will inspire other groups around the Southern Hemisphere to send us some content - Brisa del Sur and Cradle Seed Group I'm looking at you!! NOW, there's also an announcement to make this issue. For those of you who don't already know, 2017 is the twentieth year of SerpentStar! Back in 1997 the first ever issue was released to mark Alban Hefin, and there's a scan of it on the archive page of the SerpentStar website. The archive page is growing, and my aim is to have the entire back catalogue of SerpentStar available in electronic form by the end of the year. -

Primal Religion

Primal Religion Characteristics of primal religion ost world religions have holy texts: for example, Christianity has Ninian Smart (1927–2001) was a leading scholar and teacher in the field of Religious Studies. In his book The Religious Experience of Mankind (1984), he sets out some of the Myth Mthe Bible; Islam, the Qur’an; Hinduism, the Gita; and Sikhism, main features of primal religion. Myth and story-telling are the Granth Sahib. But what about those societies without a tradition important in primal religions Mana High God Ancestor veneration of writing? Many societies in the word are non-literate or oral, that is, both in their content, and A term originating in the Most, if not all, primal The human creator of the ongoing pattern of they communicate chiefly by the spoken word, and their traditions are cultures of the Pacific, religions have a concept the society, or a hero their telling. Myths explain mana is a surrounding of a High God. The High memorized. with great mana, is origins, good and evil, local force that is invisible God is above and beyond often honoured through landforms, past events, and and populated with this world; it is creator religious ritual. This may future possibilities. Oral traditions Animism deities. Mana resides and ruler of all, including be done due to perceived in chieftains, animals, souls. The High God is connections with fertility The creation myth of the The religion of oral societies has tended to be viewed as “Primal” religion is the best of a poor selection of words places, and large rocks often regarded as remote and the health of the Mongols magic or superstition, with the implication that these for the beliefs of these oral cultures. -

The Names and Epithets of the Dagda

Deep Blue Deep Blue https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/documents Research Collections Library (University of Michigan Library) 2012-04 The Names and Epithets of the Dagda Martin, Scott A. https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/138966 Downloaded from Deep Blue, University of Michigan's institutional repository The Names and Epithets of the Dagda Scott A. Martin, April 2012 Aed Abaid Essa Ruaid misi .i. dagdia druidechta Tuath De Danann 7 in Ruad Rofhessa 7 Eochaid Ollathair mo tri hanmanna. “I am Aed Abaid of Ess Rúaid, that is, the Good God of wizardry of the Túatha Dé Danann, and the Rúad Rofhessa, and Eochaid Ollathair are my three names.” (Bergin 1927) This opening line from “How the Dagda Got His Magic Staff” neatly summarizes the names by which the Dagda is known in the surviving Irish manuscripts. Translations for these names begin to shed some light on the character of this deity: the “Good God,” the “Red/Mighty One of Great Knowledge,” and “Horseman Great-father.” What other information can be gleaned about the Dagda from the way in which he is named? This essay will examine the descriptions and appellations attached to the Dagda in various texts in an attempt to provide some further answers to this question. It should be emphasized at the outset that the conclusions below are intended to enrich our religious, rather than scholarly, understanding of the Dagda, and that some latitude should be afforded the interpretations on this basis. The glossary Cóir Anmann (The Fitness of Names) contains adjacent entries for the Dagda under each of his three names (Stokes 1897: 354-357): 150. -

Test Abonnement

L E X I C O N O F T H E W O R L D O F T H E C E L T I C G O D S Composed by: Dewaele Sunniva Translation: Dewaele Sunniva and Van den Broecke Nadine A Abandinus: British water god, but locally till Godmanchester in Cambridgeshire. Abarta: Irish god, member of the de Tuatha De Danann (‘people of Danu’). Abelio, Abelionni, Abellio, Abello: Gallic god of the Garonne valley in South-western France, perhaps a god of the apple trees. Also known as the sun god on the Greek island Crete and the Pyrenees between France and Spain, associated with fertility of the apple trees. Abgatiacus: ‘he who owns the water’, There is only a statue of him in Neumagen in Germany. He must accompany the souls to the Underworld, perhaps a heeling god as well. Abhean: Irish god, harpist of the Tuatha De Danann (‘people of Danu’). Abianius: Gallic river god, probably of navigation and/or trade on the river. Abilus: Gallic god in France, worshiped at Ar-nay-de-luc in Côte d’Or (France) Abinius: Gallic river god or ‘the defence of god’. Abna, Abnoba, Avnova: goddess of the wood and river of the Black Wood and the surrounding territories in Germany, also a goddess of hunt. Abondia, Abunciada, Habonde, Habondia: British goddess of plenty and prosperity. Originally she is a Germanic earth goddess. Accasbel: a member of the first Irish invasion, the Partholans. Probably an early god of wine. Achall: Irish goddess of diligence and family love. -

Celts and Romans: the Transformation from Natural to Civic Religion Matthew at Ylor Kennedy James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2012 Celts and Romans: The transformation from natural to civic religion Matthew aT ylor Kennedy James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Kennedy, Matthew Taylor, "Celts and Romans: The transformation from natural to civic religion" (2012). Masters Theses. 247. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/247 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Celts and Romans: The Transformation from Natural to Civic Religion Matthew Kennedy A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History April 2012 Dedication To Verity, whose faith has been unwavering, and to my mother whose constant encouragement has let me reach this point. ii Table of Contents Dedication…………………………………………………………………………......ii Abstract……………………………………………………………………………….iv I. Introduction……………………………………………………………………1 II. Chapter 1: Early Roman Religion…..…………………………………………7 III. Chapter 2: Transition to Later Roman Religion.……………………………..23 IV. Chapter 3: Celtic Religion.…………………………………………………..42 V. Epilogue and Conclusion…………………………………………………….65 iii Abstract This paper is a case study dealing with cultural interaction and religion. It focuses on Roman religion, both before and during the Republic, and Celtic religion, both before and after Roman conquest. For the purpose of comparing these cultures two phases of religion are defined that exemplify the pagan religions of this period. -

196 Proceedings of the Society, January 14, 1929

6 19 PROCEEDING E SOCIETYTH F O S , JANUAR , 1929Y14 . III. A CELTIC GOD ON A SCOTTISH SCULPTURED STONE. BY DONALD A. MACKENZIE, F.S.A.ScoT. r Nationaou n I l Museu replica m s i vera f ao y remarkable sculptured stone from Meigle, on which are three figures in relief. The thoroughly pagan character of the group takes the eye at once. Mr Romilly Alien has suggested thacentrae th t l figur t usua no "s i e a s li triton, t i t "bu to find tritons in arbitrary association with land animals. On one side of this figure is a mythological boar, and on the other a convention- alised wolf e flatteneth , d hea f whic do suggesy hma a leopardt t i t bu , Pig. 1. The Meigle .Stone, showing mythological figure between two animals. must not be overlooked that animals with flattened heads are in folk- tales the reputed leaders of herds of supernatural animals (fig. 1). It is evident that these animals on the Meigle stone had a symbolic relationship to the so-called "triton." The group, indeed, is strongly reminiscen e Cernunnoth e plaquee f th o th t f f o o sse grouon n o p Gundestrup cauldron whic s preservei h e Nationath n i d l Museum, Copenhagen. Cernunnos, the "squatting god," is there shown between a deer and wolf (or hysena) grasping a horned and looping snake in his left hand. His name is believed to be derived from cern, horned, which had the secondary meaning of " victory."J In my recently published book Buddhism in Pre-Christian Britain I gave a good deal of evidence regarding the existence of the Cernunnos cult in ancient Britain and Ireland before my attention had been arrested by this unique Meigle stone Jubainvillee D notee . -

Cernunnos+Fall+2019.Pdf

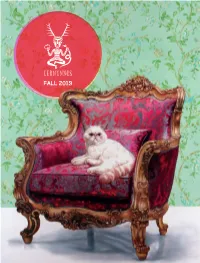

fall 2019 Cernunnos is a new publishing house showcasing books that inspire and intrigue table of contents Fall 2019 2 Pillowy THE ART OF DAVE COOPER 3 Massa Confusa THE ART OF CHRISTIAN REX VAN MINNEN 4 Tom of Finland THE OFFICIAL LIFE AND WORK OF A GAY HERO 6 the art of the devil AN ILLUSTRATED HISTORY 8 Cats rock FELINES IN ART AND POP CULTURE 10 best friends forever THE GREATEST COLLECTION OF TAXIDERMY DOGS ON EARTH 11 H. P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life BY MICHEL HOUELLEBECQ 12 Nightmares of Halloween Past BY GARY BASEMAN 14 I love to hate fashion REAL QUOTES AND WHISPERS BEHIND THE RUNWAY 16 the devil on the level BY MONDO & JOHNNY SAMPSON 17 eyes without a face BY JASON EDMISTON 18 My neighbor hayao ART INSPIRED BY THE FILMS OF MIYAZAKI backlist 20 the Addams family 21 christmas Nightmare • zoologia BY STAN MANOUKIAN 22 Mark Ryden 23 marion peck 24 ron english • tomer hanuka 25 ryan HESHKA • Maly Siri 26 border bang BY JORGE R. GUTIÉRREZ 27 Geek-Art • geek tattoo 28 hi-fructose • CRAFT THE SEASONS BY NATHALIE LÉTÉ 29 snap+share • louis stettner 30 Anatomy Rocks 31 Beards rock 32 binge watching cities 33 The Little Prince FALL RIGHTS: WORLD ENGLISH 2019 Pillowy HIGHLIGHTS THE ART OF DAVE COOPER • First complete monograph covering all of Dave Cooper’s work: By DAVE COOPER illustrations, paintings, toys, and animation • Includes forewords by the cult painter Tara McPherson and by the legendary From his queen of pin-up art and Playboy Magazine contributor, Olivia De psychedelic Berardinis cartoons to • Popular author website: his critically www.davegraphics.com acclaimed comic SPECIFICATIONS books and his • Page Count: 300 vivid paintings, • Illus/Inserts: 450 illustrations and photographs Dave Cooper is • Dimensions: 8 5/8 x 11 1/4” a unique artist • Format: Hardcover who intrigues and PUB DATE: OCTOBER 2019 ART fascinates. -

Sheela-Na-Gig: Ilmiö Ja Historia

Whore, Witch, Saint, Goddess? Sheela-na-gig: ilmiö ja historia Ilona Tuomi Johdanto My�häiskeskiajalta peräisin olevat Sheela-na-gig-veistokset ovat viime aikoina vakiinnuttaneet asemansa populaarikulttuurissa. Näistä alastomista naishahmoista on tullut ikoneita niin kirjojen kansiin, koruihin kuin koriste-esineisiinkin, ja niille on Internetissä perustettu lukuisia ’fanisivustoja’1. Taiteilijat noteerasivat Sheelojen taipumuksen ihastuttaa ja vihastuttaa jo tätä ennen, ja Sheelat ovat olleetkin inspiraation lähde sekä kirjallisuudessa, musiikissa että kuvataiteessa.2 Suomalaisille television katsojille Sheelat saattoivat tulla tutuiksi irlantilaisesta televisiosarjasta Ballykissangel. Sarjan jaksossa nimeltä Rock Bottom kylän väkeä hätkähdytti alaston naisveistos, jota arkeologit olivat tulleet noutamaan kylästä tarkempaa tutkimusta varten.3 Mitä Sheela-na-gig-veistokset sitten oikein ovat? A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology kuvaa Sheeloja irlantilaisiksi kiviveistoksiksi, jotka kuvaavat alastonta naista, jonka jalat ovat etäällä toisistaan ja siten paljastavat vaginan (MacKillop 1998, 385). Sheelat ovat tyypillisesti joko seisovassa tai kyykyssä olevassa asennossa, ja usein toinen tai molemmat kädet koskettavat sukupuolielimiä tai ainakin osoittavat niiden suuntaan. Yleensä sukupuolielimiä on painotettu lisäksi liioittelemalla niiden kokoa ja yksityiskohtia. Sheeloja on l�ydetty tusinan verran Länsi-Euroopan eri osista, mutta ylivoimaisesti eniten Brittein saarilta, eritoten Irlannista, jossa veistoksia on yli sata. Suurin osa veistoksista on sijoitettu joko kirkkojen ja luostarien seiniin, lähelle ovea tai ikkunaa, sekä linnojen seiniin ja muureihin. 1 Katso esim. www.sheelanagig.org, www.irelands-sheelanagigs.org/archive, www.beyond- the-pale.org.uk/sheela1.htm, www.bandia.net/sheela/SheelaFront.html ja www. geocities. com/wellesley/1752/sheela.html. Kaikki sivustot luettu 24.7.2009. 2 Esimerkkeinä Nobel-kirjailija Seamus Heaneyn runo Sheelagh na Gig at Kilpeck (Station Island. 1985. -

Introduction to Druidry (Celtic Neo-Paganism) the Neo-Pagan

Introduction to Druidry (Celtic Neo-Paganism) The Neo-Pagan movement is a wide spread, diverse form of contemporary spirituality. It encompasses spiritual revival or reconstruction movements that draw upon the pre-Christian spiritual traditions of Eastern and Western Europe, the British Isles, as well as traditions from Africa, Asia, and North America. In a more specific sense, however, the term "neo-paganism" has come to refer almost entirely to pre-Christian revival or reconstruction movements based in the traditions of Europe and the UK. Wicca, or contemporary Witchcraft, is probably the most popular and widespread of these neo-pagan movements. A second popular version of contemporary neo-paganism is Celtic Neo-Paganism, or Druidism. As we will see, many of the elements of contemporary Witchcraft are also to be found in Celtic Druidry, for Witchcraft has borrowed heavily from celtic sources. There are also considerable differences between Celtic neo-paganism and contemporary Witchcraft, however, and you should watch for those as you are reading the material. Although there is considerable overlap in beliefs and membership, contemporary Celtic Druidry is a separate religious system within the broader Neo-pagan movement from its sister tradition of Witchcraft. Historical Influences and Precursors As with contemporary Witchcraft, in order to understand contemporary Celtic Neo- Paganism it is necessary to explore some of the precursors to the modern religious movement. Celtic neo-paganism has three main sources of inspiration. Palaeo-Pagan Druidism The first source of inspiration, referred by neo-pagan scholar and ADF Arch Druid Isaac Bonewits as "paleo-pagan Druidism," are the beliefs, philosophies, practices and culture of Celtic peoples in pre-Christian times.