M4D 2010 10-11 November 2010 Kampala, Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nokia in 2010 Review by the Board of Directors and Nokia Annual Accounts 2010

Nokia in 2010 Review by the Board of Directors and Nokia Annual Accounts 2010 Key data ........................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Review by the Board of Directors 2010 ................................................................................................................ 3 Annual Accounts 2010 Consolidated income statements, IFRS ................................................................................................................ 16 Consolidated statements of comprehensive income, IFRS ............................................................................. 17 Consolidated statements of financial position, IFRS ........................................................................................ 18 Consolidated statements of cash flows, IFRS ..................................................................................................... 19 Consolidated statements of changes in shareholders’ equity, IFRS ............................................................. 20 Notes to the consolidated financial statements ................................................................................................ 22 Income statements, parent company, FAS .......................................................................................................... 66 Balance sheets, parent company, FAS .................................................................................................................. -

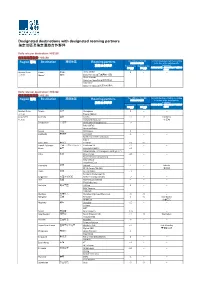

Designated Destinations with Designated Roaming Partners 指定地區及指定漫遊合作夥伴

Designated destinations with designated roaming partners 指定地區及指定漫遊合作夥伴 Daily rate per destination: HK$138 每日每地區收費: HK$138 漫遊地區 Time difference from HK For multi time zones, it will be according Region 區域 Destination Roaming partners 與香港的時間差別 to the time of the capital/specific 漫遊合作夥伴 Standard time Daylight saving destination* 標準時間 夏令時間 如設有多個時區,則按首都或以下地區的時 (hr/小時) (hr/小時) 間計算* Greater China China^ 中國^ China Mobile 0 -- -- 大中華 Macau^ 澳門^ [Only for China][只適用於中國] China Unicom [Only for China][只適用於中國] SmarTone [Only for Macau][只適用於澳門] Daily rate per destination: HK$198 每日每地區收費: HK$198 漫遊地區 Time difference from HK For multi time zones, it will be according Region 區域 Destination Roaming partners 與香港的時間差別 to the time of the capital/specific 漫遊合作夥伴 destination* Standard time Daylight saving 如設有多個時區,則按首都或以下地區的時 標準時間 夏令時間 間計算* (hr/小時) (hr/小時) Greater China Taiwan 台灣 Chunghwa 0 -- -- 大中華 Taiwan Mobile Asia-Pacific Australia 澳洲 Telstra +2 +3 Canberra 亞太區 Vodafone Australia 坎培拉 Bangladesh 孟加拉 Airtel (Warid Bangladesh) -2 -- -- Robi (AKTel) GrameenPhone Brunei 汶萊 DST Comm. 0 -- -- Cambodia 柬埔寨 CamGSM -1 -- -- Metfone (Viettel Cambodia) Smart East Timor 東帝汶 Telemor +1 +1 -- French Polynesia 法國 -法屬玻利尼西亞 Tikiphone SA +2 -- -- Guam 關島 DOCOMO PACIFIC +2 Pulse Mobile, LLC (Teleguam Holdings LLC) India 印度 Bharti Airtel -2.5 -- -- Bharti Hexacom (Rajasthan) Idea Cellular Vodafone Essar Indonesia 印尼 Indosat -1 -- Jakarta PT. XL Axiata Tbk (XL) 雅加達 Japan 日本 NTT DoCoMo +1 -- -- Softbank (Vodafone KK) Kyrgyzstan 吉爾吉斯斯坦 Beeline KG (Sky Mobile) -2 -- -- Laos 老撾 Star -

Member Directory

D DIRECTORY Member Directory ABOUT THE MOBILE MARKETING ASSOCIATION (MMA) Mobile Marketing Association Member Directory, Spring 2008 The Mobile Marketing Association (MMA) is the premier global non- profit association established to lead the development of mobile Mobile Marketing Association marketing and its associated technologies. The MMA is an action- 1670 Broadway, Suite 850 Denver, CO 80202 oriented organization designed to clear obstacles to market USA development, establish guidelines and best practices for sustainable growth, and evangelize the mobile channel for use by brands and Telephone: +1.303.415.2550 content providers. With more than 600 member companies, Fax: +1.303.499.0952 representing over forty-two countries, our members include agencies, [email protected] advertisers, handheld device manufacturers, carriers and operators, retailers, software providers and service providers, as well as any company focused on the potential of marketing via mobile devices. *Updated as of 31 May, 2008 The MMA is a global organization with regional branches in Asia Pacific (APAC); Europe, Middle East & Africa (EMEA); Latin America (LATAM); and North America (NA). About the MMA Member Directory The MMA Member Directory is the mobile marketing industry’s foremost resource for information on leading companies in the mobile space. It includes MMA members at the global, regional, and national levels. An online version of the Directory is available at http://www.mmaglobal.com/memberdirectory.pdf. The Directory is published twice each year. The materials found in this document are owned, held, or licensed by the Mobile Marketing Association and are available for personal, non-commercial, and educational use, provided that ownership of the materials is properly cited. -

UMTS: Alive and Well

TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE…………………………………………………………………...……………………………… 5 1 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 10 2 PROGRESS OF RELEASE 99, RELEASE 5, RELEASE 6, RELEASE 7 UMTS-HSPA .......... 12 2.1 PROGRESS TIMELINE .................................................................................................................. 12 3 PROGRESS AND PLANS FOR RELEASE 8: EVOLVED EDGE, HSPA EVOLVED/HSPA+ AND LTE/EPC ............................................................................................................................ 19 4 THE GROWING DEMANDS FOR WIRELESS DATA APPLICATIONS ................................... 26 4.1 WIRELESS DATA TRENDS AND FORECASTS ................................................................................. 28 4.2 WIRELESS DATA REVENUE ......................................................................................................... 29 4.3 3G DEVICES............................................................................................................................... 31 4.4 3G APPLICATIONS ...................................................................................................................... 34 4.5 FEMTOCELLS ............................................................................................................................. 41 4.6 SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................. -

Online Industry

July 2009 1st Half Mergers and Acquisitions Trends Report ONLINE INDUSTRY 1st Half 2009 Key Highlights IN THIS ISSUE • The most active buyer in the Online Industry, in terms of volume of M&A Market Overview transactions announced for the 1st Figure 1. M&A Market Half of 2009, was IAC/InterActiveCorp Dynamics - 1st Half with 4 transactions. These include Figure 2. Median Enterprise the acquisitions of SportsPickle.com, Market Hardware, Inc., Urbanspoon, Value Multiples - 1st Half and Sendori, Inc. Transaction Analysis • The segment with the largest transaction volume for the 1st Half of 2009 was Figure 3. Bell Curve Histogram SaaS/ASP with 92 transactions. - 1st Half Figure 4. Distribution Table - • In the 1st Half of 2009, there were 30 1st Half financially sponsored transactions with an aggregate value of $355 million. These figures represent 11 percent of Figure 1. 1st Half 2007 - 2009 value and volume Strategic vs. Financial Comparison comparison the total volume and 5 percent of the Figure 5. M&A Dynamics By total value, respectively. Transaction Type - 1st Half ‘09 Figure 6. Transaction Type - 1st Half 1st Half 2009 Key Trends • Total transaction volume in the 1st Half of 2009 decreased by 22 percent over the 1st Half of Purchaser Analysis 2008 from 364 in 2008 to 285 in 2009. Figure 7. Top Ten Notable • Total transaction value in the 1st Half of 2009 decreased by 49 percent over the 1st Half of Transactions - 1st Half 2009 2008, from $15.03 billion in 2008 to $7.68 billion in 2009. Figure 8. Median Enterprise • The segment with the largest increase in value in the 1st Half of 2009 over the 1st Half of Value/Revenue Multiples By Size 2008 was E-Commerce with a 17 percent increase from $2.81 billion in 2008 to Transaction Volume By Segment $3.29 billion in 2009. -

International SMS - Supporting Destinations and Network Operators* 國際短訊服務 - 支援地方及網絡商*

International SMS - Supporting Destinations and Network Operators* 國際短訊服務 - 支援地方及網絡商* Destinations 地 方 Network Operator 網 絡 商 Afghanistan 阿富汗 MTN Afghanistan (Areeba) AWCC Roshan (TDCA) Aland 奧蘭島 (芬) Alands Telekommunikation Elisa Finland Sonera Albania 阿爾巴尼亞 AMC Eagle Mobile Vodafone Albania Algeria 亞爾及利亞 Djezzy Wataniya Algeria Andorra 安道爾 Andorra Telecom Angola 安哥拉 Unitel Angola Anguilla (West Indies) 安圭拉島 (西印度群島) C&W (West Indies) Digicel Antigua (West Indies) 安提瓜 (西印度群島) C&W (West Indies) Digicel Argentina 阿根廷 AMX (Claro Argentina) Movistar Argentina Telecom Personal Armenia 亞美尼亞 ArmenTel Vivacell-MTS Aruba 阿魯巴 SETAR Digicel Australia 澳洲 'yes' Optus Telstra Vodafone Australia Austria 奧地利 Orange Austria T-Mobile Austria A1 Telekom Austria AG (MobilKom) Azerbaijan 亞塞拜疆 Azercell Azerfon Bakcell Azores 亞速爾群島(葡) Vodafone Portugal TMN Bahamas 巴哈馬 BTC Bahrain 巴林 Batelco STC Bahrain (VIVA) zain BH (Vodafone Bahrain) Bangladesh 孟加拉 Robi (AKTel) Banglalink GrameenPhone Airtel (Warid Bangladesh) Barbados (West Indies) 巴巴多斯 (西印度群島) C&W (West Indies) Digicel Barbuda (West Indies) 巴布達 (西印度群島) C&W (West Indies) Digicel Belarus 白俄羅斯 MTS Belarus FE VELCOM (MDC) Belgium 比利時 Base NV/SA (KPN) MobiStar Belgacom Belize 伯利茲 BTL Benin 貝寧 Etisalat Benin S.A Spacetel Benin (MTN-Areeba) Bermuda 百慕達 Digicel Bhutan 不丹 B-Mobile Bhutan Bolivia 波利維亞 Entel Bornholm 波恩荷爾摩島 (丹) Telenor A/S Telia Danmark TDC A/S Bosnia and Herzegovina 波斯尼亞 HT Mobile Botswana 博茨瓦納 Orange Botswana Brazil 巴西 Brasil Telecom Celular (Oi Brazil) Claro Brasil TIM Brasil TNL PCS British Virgin -

A Fugitive Success That Finland Is Quickly Becoming a Victim of Its Own Success

Professor Charles Sabel from Columbia Law School and Professor AnnaLee Saxenian from UC Berkeley argue in their book A Fugitive Success that Finland is quickly becoming a victim of its own success. In recent decades Finnish firms in the forest products and telecommunications industries have become world leaders. But the kind of discipline that made this success possible, and the public policies that furthered it, is unlikely to secure it in the future. Efficiency improvements and incremental A Fugitive Success innovations along the current business trajectory will gradually lead these industries into a dead-end unless they use innovation as a vehicle for transforming themselves into new higher value businesses. Saxenian and Sabel raise some serious concerns about the readiness of these industries, and the Finnish innovation system as a whole, for the needed transformation. A Fugitive Success is required reading for A Fugitive Success those involved in the development of the Finnish innovation environment and Finland’s Economic Future implementing the new national innovation strategy. Charles Sabel and AnnaLee Saxenian Sitra Reports 80 Sitra Reports the Finnish Innovation Fund ISBN 978-951-563-639-3 Itämerentori 2, P.O. Box 160, FI-00181 Helsinki, Finland, www.sitra.fi/en ISSN 1457-5728 80 Telephone +358 9 618 991, fax +358 9 645 072 URL: http://www.sitra.fi A Fugitive Success Finland’s Economic Future Sitra Reports 80 A Fugitive Success Finland’s Economic Future Charles Sabel AnnaLee Saxenian Sitra • HelSinki 3 Sitra Reports 80 Layout: Sisko Honkala Cover picture: Shutterstock © Sabel, Saxenian and Sitra ISBN 978-951-563-638-6 (paperback) ISSN 1457-571X (paperback) ISBN 978-951-563-639-3 (URL:http://www.sitra.fi) ISSN 1457-5728 (URL:http://www.sitra.fi) The publications can be ordered from Sitra, tel. -

Microsoft Acquires Massive, Inc

S T A N F O R D U N I V E R S I T Y! 2 0 0 7 - 3 5 3 - 1! W W W . C A S E W I K I . O R G! R e v . M a y 2 9 , 2 0 0 7 MICROSOFT ACQUIRES MASSIVE, INC. May 4th, 2006 T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1. Introduction 2. Industry Overview 2.1. The Advertising Opportunity Within Video Games 2.2. Market Size and Demographics 2.3. Video Games and Advertising 2.4. Market Dynamics 3. Massive, Inc. ! Company Background 3.1. Founding of Massive 3.2. The Financing of Massive 3.3. Product Launch / Technology 3.4. The Massive / Microsoft Deal 4. Microsoft, Inc. within the Video Game Industry 4.1. Role as a Game Publisher / Developer 4.2. Acquisitions 4.3. Role as an Electronic Advertising Network 4.4. Statements Regarding the Acquisition of Massive, Inc. 5. Exhibits 5.1. Table of Exhibits 6. References ! 2 0 0 7 - 3 5 3 - 1! M i c r o s o f t A c q u i s i t i o n o f M a s s i v e , I n c .! I N T R O D U C T I O N In May 2007, Microsoft Corporation was a company in transition. Despite decades of dominance in its core markets of operating systems and desktop productivity software, Mi! crosoft was under tremendous pressure to create strongholds in new market spaces. -

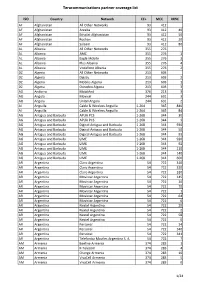

Teracommunications Partner Coverage List

Teracommunications partner coverage list ISO Country Network CC+ MCC MNC AF Afghanistan All Other Networks 93 412 AF Afghanistan Areeba 93 412 40 AF Afghanistan Etisalat Afghanistan 93 412 50 AF Afghanistan Roshan 93 412 20 AF Afghanistan Salaam 93 412 80 AL Albania All Other Networks 355 276 AL Albania AMC 355 276 1 AL Albania Eagle Mobile 355 276 3 AL Albania Plus Albania 355 276 4 AL Albania Vodafone Albania 355 276 2 DZ Algeria All Other Networks 213 603 DZ Algeria Djezzy 213 603 2 DZ Algeria Mobilis Algeria 213 603 1 DZ Algeria Ooredoo Algeria 213 603 3 AD Andorra MobilAnd 376 213 3 AO Angola Movicel 244 631 3 AO Angola Unitel Angola 244 631 2 AI Anguilla Cable & Wireless Anguilla 1-264 365 840 AI Anguilla Cable & Wireless Anguilla 1-264 365 84 AG Antigua and Barbuda APUA PCS 1-268 344 30 AG Antigua and Barbuda APUA PCS 1-268 344 3 AG Antigua and Barbuda Digicel Antigua and Barbuda 1-268 344 930 AG Antigua and Barbuda Digicel Antigua and Barbuda 1-268 344 50 AG Antigua and Barbuda Digicel Antigua and Barbuda 1-268 344 93 AG Antigua and Barbuda LIME 1-268 344 920 AG Antigua and Barbuda LIME 1-268 344 92 AG Antigua and Barbuda LIME 1-268 344 110 AG Antigua and Barbuda LIME 1-268 344 140 AG Antigua and Barbuda LIME 1-268 344 600 AR Argentina Claro Argentina 54 722 310 AR Argentina Claro Argentina 54 722 320 AR Argentina Claro Argentina 54 722 330 AR Argentina Movistar Argentina 54 722 145 AR Argentina Movistar Argentina 54 722 10 AR Argentina Movistar Argentina 54 722 70 AR Argentina Movistar Argentina 54 722 1 AR Argentina Movistar Argentina 54 722 64 AR Argentina Movistar Argentina 54 722 6 AR Argentina Nextel Argentina 54 722 20 AR Argentina Nextel Argentina 54 722 2 AR Argentina Nextel Argentina 54 722 58 AR Argentina Nextel Argentina 54 722 0 AR Argentina Personal 54 722 34 AR Argentina Personal 54 722 340 AR Argentina Personal 54 722 341 AR Argentina Telefonica Moviles Argentina S. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 20F Nokia Corporation

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on March 5, 2009. UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20F ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2008 Commission file number 113202 Nokia Corporation (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Republic of Finland (Jurisdiction of incorporation) Keilalahdentie 4, P.O. Box 226, FI00045 NOKIA GROUP, Espoo, Finland (Address of principal executive offices) Kaarina Sta˚hlberg, Vice President, Assistant General Counsel Telephone: +358 (0) 7 18008000, Facsimile: +358 (0) 7 18038503 Keilalahdentie 4, P.O. Box 226, FI00045 NOKIA GROUP, Espoo, Finland (Name, Telephone, Email and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the “Exchange Act”): Name of each exchange Title of each class on which registered American Depositary Shares New York Stock Exchange Shares New York Stock Exchange(1) (1) Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares representing these shares, pursuant to the requirements of the Securities and Exchange Commission. Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Exchange Act: None Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act: None Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the registrant’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report. -

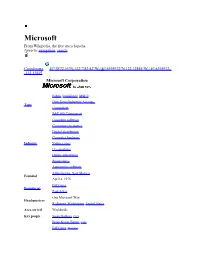

Microsoft from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search

Microsoft From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Coordinates: 47°38′22.55″N 122°7′42.42″W / 47.6395972°N 122.12845°W / 47.6395972; -122.12845 Microsoft Corporation Public (NASDAQ: MSFT) Dow Jones Industrial Average Type Component S&P 500 Component Computer software Consumer electronics Digital distribution Computer hardware Industry Video games IT consulting Online advertising Retail stores Automotive software Albuquerque, New Mexico Founded April 4, 1975 Bill Gates Founder(s) Paul Allen One Microsoft Way Headquarters Redmond, Washington, United States Area served Worldwide Key people Steve Ballmer (CEO) Brian Kevin Turner (COO) Bill Gates (Chairman) Ray Ozzie (CSA) Craig Mundie (CRSO) Products See products listing Services See services listing Revenue $62.484 billion (2010) Operating income $24.098 billion (2010) Profit $18.760 billion (2010) Total assets $86.113 billion (2010) Total equity $46.175 billion (2010) Employees 89,000 (2010) Subsidiaries List of acquisitions Website microsoft.com Microsoft Corporation is an American public multinational corporation headquartered in Redmond, Washington, USA that develops, manufactures, licenses, and supports a wide range of products and services predominantly related to computing through its various product divisions. Established on April 4, 1975 to develop and sell BASIC interpreters for the Altair 8800, Microsoft rose to dominate the home computer operating system (OS) market with MS-DOS in the mid-1980s, followed by the Microsoft Windows line of OSes. Microsoft would also come to dominate the office suite market with Microsoft Office. The company has diversified in recent years into the video game industry with the Xbox and its successor, the Xbox 360 as well as into the consumer electronics market with Zune and the Windows Phone OS. -

Form 20-F 2008 Form 20-F Nokia Form 20-F 2008 Copyright © 2009

Nokia 20-F Form 2008 Form 20-F 2008 Copyright © 2009. Nokia Corporation. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2009. Nokia Corporation. of Nokia Corporation. trademarks registered Nokia and Connecting People are As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on March 5, 2009. UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20F ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2008 Commission file number 113202 Nokia Corporation (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Republic of Finland (Jurisdiction of incorporation) Keilalahdentie 4, P.O. Box 226, FI00045 NOKIA GROUP, Espoo, Finland (Address of principal executive offices) Kaarina Sta˚hlberg, Vice President, Assistant General Counsel Telephone: +358 (0) 7 18008000, Facsimile: +358 (0) 7 18038503 Keilalahdentie 4, P.O. Box 226, FI00045 NOKIA GROUP, Espoo, Finland (Name, Telephone, Email and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the “Exchange Act”): Name of each exchange Title of each class on which registered American Depositary Shares New York Stock Exchange Shares New York Stock Exchange(1) (1) Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares representing these shares, pursuant to the requirements of the Securities and Exchange Commission. Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Exchange Act: None Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act: None Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the registrant’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report.