Soparanos Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STEPHEN MARK, ACE Editor

STEPHEN MARK, ACE Editor Television PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. DELILAH (series) Various OWN / Warner Bros. Television EP: Craig Wright, Oprah Winfrey, Charles Randolph-Wright NEXT (series) Various Fox / 20th Century Fox Television EP: Manny Coto, Charlie Gogolak, Glenn Ficarra, John Requa SNEAKY PETE (series) Various Amazon / Sony Pictures Television EP: Blake Masters, Bryan Cranston, Jon Avnet, James Degus GREENLEAF (series) Various OWN / Lionsgate Television EP: Oprah Winfrey, Clement Virgo, Craig Wright HELL ON WHEELS (series) Various AMC / Entertainment One Television EP: Mark Richard, John Wirth, Jeremy Gold BLACK SAILS (series) Various Starz / Platinum Dunes EP: Michael Bay, Jonathan Steinberg, Robert Levine, Dan Shotz LEGENDS (pilot)* David Semel TNT / Fox 21 Prod: Howard Gordon, Jonathan Levin, Cyrus Voris, Ethan Reiff DEFIANCE (series) Various Syfy / Universal Cable Productions Prod: Kevin Murphy GAME OF THRONES** (season 2, ep.10) Alan Taylor HBO EP: Devid Benioff, D.B. Weiss BOSS (pilot* + series) Various Starz / Lionsgate Television EP: Farhad Safinia, Gus Van Sant, THE LINE (pilot) Michael Dinner CBS / CBS Television Studios EP: Carl Beverly, Sarah Timberman CANE (series) Various CBS / ABC Studios Prod: Jimmy Smits, Cynthia Cidre, MASTERS OF SCIENCE FICTION (anthology series) Michael Tolkin ABC / IDT Entertainment Jonathan Frakes Prod: Keith Addis, Sam Egan 3 LBS. (series) Various CBS / The Levinson-Fontana Company Prod: Peter Ocko DEADWOOD (series) Various HBO 2007 ACE Eddie Award Nominee | 2006 ACE Eddie Award Winner Prod: David Milch, Gregg Fienberg, Davis Guggenheim 2005 Emmy Nomination WITHOUT A TRACE (pilot) David Nutter CBS / Warner Bros. Television / Jerry Bruckheimer TV Prod: Jerry Bruckheimer, Hank Steinberg SMALLVILLE (pilot + series) David Nutter (pilot) CW / Warner Bros. -

The Sopranos Episode Guide Imdb

The sopranos episode guide imdb Continue Season: 1 2 3 4 5 6 OR Year: 1999 2000 2001 2002 2004 2006 2007 Season: 1 2 3 4 5 6 OR Year: 1999 2000 2001 200102 200204 2006 2007 Season: 1 2 3 3 4 5 6 OR Year: 1999 2000 2001 2002 2004 2006 2007 Edit It's time for the annual ecclera and, as usual, Pauley is responsible for the 5 day affair. It's always been a money maker for Pauley - Tony's father, Johnny Soprano, had control over him before him - but a new parish priest believes that the $10,000 Poly contributes as the church's share is too low and believes $50,000 would be more appropriate. Pauley shies away from that figure, at least in part, he says, because his own spending is rising. One thing he does to save money to hire a second course of carnival rides, something that comes back to haunt him when one of the rides breaks down and people get injured. Pauley is also under a lot of stress after his doctor dislikes the results of his PSA test and is planning a biopsy. When Christopher's girlfriend Kelly tells him he is pregnant, he asks her to marry him. He is still struggling with his addiction however and falls off the wagon. Written by GaryKmkd Plot Summary: Add a Summary Certificate: See All The Certificates of the Parents' Guide: Add Content Advisory for Parents Edit Vic Noto plays one of the bikies from the Vipers group that Tony and Chris steal wine from. -

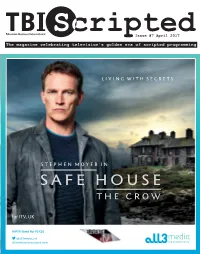

STEPHEN MOYER in for ITV, UK

Issue #7 April 2017 The magazine celebrating television’s golden era of scripted programming LIVING WITH SECRETS STEPHEN MOYER IN for ITV, UK MIPTV Stand No: P3.C10 @all3media_int all3mediainternational.com Scripted OFC Apr17.indd 2 13/03/2017 16:39 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. Brand new second season. based on the acclaimed dilemmas, this five-part series Winner – TVFI Prix Export Fiction Award 2017. author Åsa Larsson’s tells the amazing true story of CANAL+ CREATION ORIGINALE best-selling crime novels. a notorious criminal barrister. Sinister events engulf a group of friends Ellen follows a difficult teenage girl trying A husband searches for the truth when A country pub singer has a chance meeting when they visit the abandoned Black to take control of her life in a world that his wife is the victim of a head-on with a wealthy city hotelier which triggers Lake ski resort, the scene of a horrific would rather ignore her. Winner – Best car collision. Was it an accident or a series of events that will change her life crime. Single Drama Broadcast Awards 2017. something far more sinister? forever. New second series in production. MIPTV Stand C20.A banijayrights.com Banijay_TBI_DRAMA_DPS_AW.inddScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay Apr17.indd 2 1 15/03/2017 12:57 15/03/2017 12:07 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. -

Pocket Product Guide 2006

THENew Digital Platform MIPTV 2012 tm MIPTV POCKET ISSUE & PRODUCT OFFILMGUIDE New One Stop Product Guide Search at the Markets Paperless - Weightless - Green Read the Synopsis - Watch the Trailer BUSINESSC onnect to Seller - Buy Product MIPTVDaily Editions April 1-4, 2012 - Unabridged MIPTV Product Guide + Stills Cher Ami - Magus Entertainment - Booth 12.32 POD 32 (Mountain Road) STEP UP to 21st Century The DIGITAL Platform PUBLISHING Is The FUTURE MIPTV PRODUCT GUIDE 2012 Mountain, Nature, Extreme, Geography, 10 FRANCS Water, Surprising 10 Francs, 28 Rue de l'Equerre, Paris, Delivery Status: Screening France 75019 France, Tel: Year of Production: 2011 Country of +33.1.487.44.377. Fax: +33.1.487.48.265. Origin: Slovakia http://www.10francs.f - email: Only the best of the best are able to abseil [email protected] into depths The Iron Hole, but even that Distributor doesn't guarantee that they will ever man- At MIPTV: Yohann Cornu (Sales age to get back.That's up to nature to Executive), Christelle Quillévéré (Sales) decide. Office: MEDIA Stand N°H4.35, Tel: + GOOD MORNING LENIN ! 33.6.628.04.377. Fax: + 33.1.487.48.265 Documentary (50') BEING KOSHER Language: English, Polish Documentary (52' & 92') Director: Konrad Szolajski Language: German, English Producer: ZK Studio Ltd Director: Ruth Olsman Key Cast: Surprising, Travel, History, Producer: Indi Film Gmbh Human Stories, Daily Life, Humour, Key Cast: Surprising, Judaism, Religion, Politics, Business, Europe, Ethnology Tradition, Culture, Daily life, Education, Delivery Status: Screening Ethnology, Humour, Interviews Year of Production: 2010 Country of Delivery Status: Screening Origin: Poland Year of Production: 2010 Country of Western foreigners come to Poland to expe- Origin: Germany rience life under communism enacted by A tragicomic exploration of Jewish purity former steel mill workers who, in this way, laws ! From kosher food to ritual hygiene, escaped unemployment. -

The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams by Cynthia A. Burkhead A

Dancing Dwarfs and Talking Fish: The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams By Cynthia A. Burkhead A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University December, 2010 UMI Number: 3459290 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459290 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DANCING DWARFS AND TALKING FISH: THE NARRATIVE FUNCTIONS OF TELEVISION DREAMS CYNTHIA BURKHEAD Approved: jr^QL^^lAo Qjrg/XA ^ Dr. David Lavery, Committee Chair c^&^^Ce~y Dr. Linda Badley, Reader A>& l-Lr 7i Dr./ Jill Hague, Rea J <7VM Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate this work to my husband, John Burkhead, who lovingly carved for me the space and time that made this dissertation possible and then protected that space and time as fiercely as if it were his own. I dedicate this project also to my children, Joshua Scanlan, Daniel Scanlan, Stephen Burkhead, and Juliette Van Hoff, my son-in-law and daughter-in-law, and my grandchildren, Johnathan Burkhead and Olivia Van Hoff, who have all been so impressively patient during this process. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

Catherine Johnson

Catherine Johnson TELE-BRANDING IN TVIII The network as brand and the programme as brand In the era of TVIII, characterised by deregulation, multimedia conglomeration, expansion and increased competition, branding has emerged as a central industrial practice. Focusing on the case of HBO, a particularly successful brand in TVIII, this paper argues that branding can be understood not simply as a feature of television networks, but also as a characteristic of television programmes. It begins by examining how the network as brand is constructed and conveyed to the consumer through the use of logos, slogans and programmes. The role of programmes in the construction of brand identity is then complicated by examining the sale of programmes abroad, where programmes can be seen to contribute to the brand identity of more than one network. The paper then goes on to examine programme merchandising, an increasingly central strategy in TVIII. Through an analysis of different merchandising strategies the paper argues that programmes have come to act as brands in their own right, and demonstrates that the academic study of branding not only reveals the development of new industrial practices, but also offers a way of understanding the television programme and its consumption by viewers in a period when the texts of television are increasingly extended across a range of media platforms. TVIII, at least at this juncture, must be considered the age of brand marketing. (Rogers et al. 2002, p. 48) ‘Branding’ has emerged as a central concern of the television industry in the age of digital convergence. (Caldwell 2004, p. 305) New Review of Film and Television Studies Vol. -

A Textual Analysis of the Closer and Saving Grace: Feminist and Genre Theory in 21St Century Television

A TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF THE CLOSER AND SAVING GRACE: FEMINIST AND GENRE THEORY IN 21ST CENTURY TELEVISION Lelia M. Stone, B.A., M.P.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2013 APPROVED: Harry Benshoff, Committee Chair George Larke-Walsh, Committee Member Sandra Spencer, Committee Member Albert Albarran, Chair of the Department of Radio, Television and Film Art Goven, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Stone, Lelia M. A Textual Analysis of The Closer and Saving Grace: Feminist and Genre Theory in 21st Century Television. Master of Arts (Radio, Television and Film), December 2013, 89 pp., references 82 titles. Television is a universally popular medium that offers a myriad of choices to viewers around the world. American programs both reflect and influence the culture of the times. Two dramatic series, The Closer and Saving Grace, were presented on the same cable network and shared genre and design. Both featured female police detectives and demonstrated an acute awareness of postmodern feminism. The Closer was very successful, yet Saving Grace, was cancelled midway through the third season. A close study of plot lines and character development in the shows will elucidate their fundamental differences that serve to explain their widely disparate reception by the viewing public. Copyright 2013 by Lelia M. Stone ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapters Page 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. -

Overand out Cline of the Original TV Theme

THE 50th ANNIVERSARY OF THE BILLBOARD HOT 100 SPEAKING IN TONGUES h ay ,.JO Tough c C al- Language European Acts By Paul Sexton In February, French -Israeli pop singer Yael ABBA to Germany's Scorpions -the Náim logged the highest Hot loo chart po- language of the Hot ioo has generally sition fora French artist in 40 years -but been English. But a select band of Euro- to get there, she had to sing in English. peans has enjoyed moments of incon- While Latino acts often take Spanish - gruous glory, rarely more so than in De- language material onto the Hot 100, most cember 1963 when Belgium's Singing European artists find that their native Nun (Sister Luc -Gabrielle), held the tongue keeps them off the chart. Indeed, Kingsmen's epochal "Louie Louie" off MIKE POST'S the highest -charting French act on the the top slot with "Dominique." Some- themes, such as Hot loo remains Paul Mauriat's No. 1 what predictably, she never reached 'The Rockford Files' and 'Hill "Love Is Blue" (1868)-an instrumental. the Hot ioo again. Street Blues,' Italy had its own fleeting moment of have been a U.S. validation in the late'5os. Although staple of prime - time TV for "Volare" is Dean usually associated with decades. Martin, his version stalled at No.12 while Domenico Modugno's original, "Nel Blu Dipinto di Blu," topped the Hot loo for five weeks in 1958. Orders, "is sanguine about the de- Modugno's hit is the only foreign -lan- OverAnd Out cline of the original TV theme. -

Stephen J. Cannell, 1941-2010

STEPHEN J. CANNELL, 1941-2010 Stephen J(oseph) Cannell was born February 5, 1941 to Joseph Cannell, a Pasadena, California entrepreneur. Cannell struggled through his early school years, flunking three different grades of elementary, junior or senior high school, and regularly failing his English classes. Years later, when having one of his own children tested for dyslexia, he discovered that he had suffered from it his entire life. Never the less, he had a passionate love for writing, despite his difficulties with the written word, and set a goal for himself to become a best-selling author. After attending the University of Oregon on a football scholarship and meeting creative writing teachers that bolstered his confidence, Cannell married his high school sweetheart and went to work for his family’s business – driving a furniture truck all day. In the evenings, he set a rigorous writing schedule for himself – writing 5 hours a day, 7 days a week, on spec. He decided that his target market would be the burgeoning television scene, and after 6 years without a sale, he finally sold a script – to the series Ironside. After a few more sales, he caught the eye of the legendary writer/producer Jack Webb, who first hired him to be story editor and ultimately head writer for Adam-12. Cannell was contracted to Universal Television, writing and producing shows for that studio during the early-to-mid 1970s. While there, he produced Chase and wrote for and produced Toma, about real-life New York City detective David Toma. While producing Toma, Cannell and his mentor Roy Huggins (creator of Maverick, and many other tv series) wrote an episode that ended up getting rewritten to serve as a pilot for a series about an unorthodox Southern California P.I. -

The Picture of Abjection: Film, Fetish, and the Nature of Difference

The Picture of Abjection: Film, Fetish, and the Nature of Difference By Tina Chanter Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008. ISBN: 9780253219183. 15 illustrations, 377 pp. £19.99 (pbk) A review by Adrienne Angelo, Angelo, University of West Georgia, USA How do scholars and others with an interest in film studies and psychoanalysis engage with existing theoretical discourses on race, gender, culture and sexual difference in order to bypass the often polemicized and contested paradigm of fetishism and voyeurism, two critical modes that have dominated and continue to dominate film theory? It is this problematic that Tina Chanter explores in The Picture of Abjection: Film, Fetish and the Nature of Difference. For Chanter, drawing largely upon Kristeva's theoretical considerations of abjection, a point of entry to this endeavor lies precisely in further developing the implications of abjection as a "staging of a defensive dynamic that has the potential to significantly rework the imaginary commitments of Oedipal theory, specifically its privileging of masculinity and femininity" (17). Chanter's primary goal appears to be to develop a new critical model at the very center of which lies that which is otherwise neglected, excluded and expelled from dominant cultural discourse for being "too much", too "other". However, for as much as Chanter promotes a consideration of film and film theory, there is less an in-depth reading of films per se than a highly informed reconsideration of theoretical notions of subjectivity and the subject, one read through the lens of abjection and its destabilizing and thus subversive potential for considering marginalized identities and their representation in film theory. -

A Midsummer Nights Dream 11 'T} S , O(;;)-2 by Wilham Shakespeare

A Midsummer NightS Dream 11 't} s , o(;;)-2 by WilHam Shakespeare ~ BAm~ Tiieater BRooKLYN AcADEMY oF Music Compa11y ~~~~~~~~~ \.. ~ , •' II I II Q ,\.~ I II 1 \ } ( "' '" \ . • • !I II'" r )DO I \ ., : \ I ~\ } .. \ ;; .; 'I' ... .. _:..,... 1t ; rJ ,.I •\ y v \ YOUR MONEY GROWS LIKE MAGIC AT THE THE DIME SAVINGS BANK DF NEW YORK -..1-..ett•O•C MANHATTAN • DOWNTOWN BROOKLYN • BENSONHURST • FLATBUSH CONEY ISLAND • KINGS PLAZA • VALLEY STREAM • MASSAPEQUA HUNTINGTON STATION TABLE OF Old CONTENTS Hungary "An authentic ~ ounpany~~~~~~~ Hungarian restaurant right here in Brooklyn" Beef Goulash, Ch1cken Papnka, St uffed Cabbage, Palacsinta and other traditional dishes " Live Piano Music Nightly" The Actors 5-8 PRE-T HEATRE AND AFTER THEATRE DINNER 142 Montague St., Bklyn . Hghts. Notes on the Play 9-14 625· 1649 Production Team 15 § The Staff 16 'R(!tauranb The Actors 17-19 tel: 855-4830 Contributors 20-21 UL8-2000 Board of Directors 22 open daily for lunch and dinner till 9 P. M. Italian and A m erican Cuisine special orders upon request Flowers, plants and fruit baskets for all occasions (212) 768-6770 25th Street & 768-0800 5th Avenue Deluxe coach service following DIRECTORY BAM Theater Company Directory of Facilities a nd Services Box Office: Monday 10 00 to &.00 Tue.day throu~h ~tur performances day 10 00 to Y 00 Sunday Performance limes only Lost ond ~o und : Telephone &36-4 150 Restroom: Operu We pick you up and take you back llouse Women .ond Men. Mezzanme level. HandKapp<.·d Or c h c~t r a level Ployh ou,e: Women Orchestra l~vcl ,\.1cn .'Ae1 (to Manhattan) 1.anme lt•vel llandocapped Orchestra level Lepercq Spucc: The BAMBus Express will pick-up BAM Theater Company Wom en ,,nd Men Tht•c.H e r level Public T ele phon es.