Reimagine Victoriaville Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OBSP Screening Site Locations (Wheelchair Accessible)

OBSP Screening Site Locations Provincial Toll-Free Number: 1-800-668-9304 Regional OBSP Centres: Greater Toronto North York Women’s Centre ËB (416) 512-0601 Area (G.T.A.): 100 Sheppard Avenue East, Suite 140 North York, Ontario M2N 6N5 Hamilton Sir William Osler Health Institute ËB (905) 389-0101 565 Sanatorium Road, Suite 207 Hamilton, Ontario L9C 7N4 Kingston 786 Blackburn Mews ËB (613) 384-4284 Kingston, Ontario 1 (800) 465-8850 K7P 2N7 Ottawa Hampton Park Plaza, 1419 Carling Ave. ËB (613) 728-0777 Suite 214 (2nd Floor), Ottawa, Ontario 1 (800) 465-6226 K1Z 7L6 Thunder Bay 984 Oliver Road, 4th Floor ËB (807) 684-7777 Thunder Bay, Ontario 1 (800) 461-7031 P7B 7C7 London 339 Talbot Street ËB (519) 432-0255 London, Ontario 1 (800) 461-0640 N6A 2R5 Windsor Walker Plaza 1200, ËB (519) 253-0903 1275 Walker Road, Unit 10 Windsor, Ontario N8Y 4X9 Sudbury 4 Walford Road ËB (705) 675-2283 Sudbury, Ontario 1 (800) 661-8897 P3E 2H4 Ë - Wheelchair accessible B – French Language Services Last revised: June 19, 2009 1 OBSP Affiliated Screening Sites: The OBSP Affiliated Screening Centres are listed here below according to the Local Health Information Network (LHIN) area they are located in. To determine which LHIN you reside in, go to the following website and enter your postal code: http://www.lhins.on.ca/FindYourLHIN.aspx, or Call the ministry INFO line at 1-888-779-7767 #1 Erie St. Clair LHIN City Site Name Address Booking Number Chatham Chatham-Kent Health Alliance, Chatham Campus ËB 80 Grand Avenue West (519) 437-6012 Chatham, ON N7L 1B7 Leamington -

Council Agenda

COUNCIL AGENDA Council Chambers, City Hall, 1 Carden Street DATE Wednesday, November 18, 2015 – 5:00 p.m. Please turn off or place on non-audible all cell phones, PDAs, Blackberrys and pagers during the meeting. Disclosure of Pecuniary Interest and General Nature Thereof Downtown Parking Master Plan Presentation • Peter Cartwright, General Manager, Business Development and Enterprise • Ian Panabaker, Manager, Downtown Renewal • Cameron Walsh, Project Director Recommendation 1. That Council receive report #IDE-BDE-1510, titled “Downtown Parking Master Plan”. 2. That staff be directed to implement Scenario #3 as described in report #IDE-BDE-1510. 3. That staff be directed to work with the Downtown Advisory Committee to develop metrics which will be used to measure and determine the effect and implementation of enhanced on-street parking management and customer service strategy within the downtown. 4. That staff be directed to implement a targeted community engagement process for the purpose of creating a periphery parking management system. 5. That staff be directed to provide annual progress reports regarding the implementation of the Parking Master Plan. 6. That staff be directed to explore and report back by Q2 2016 on current and alternative opportunities to maximize economies of scale/staging of downtown enterprise projects, beginning with the Wilson Street parkade and including analysis of available procurement methods that might advance innovative ways in delivering a quality designed and built structure(s). ADJOURNMENT Page 1 of 1 CITY OF GUELPH COUNCIL AGENDA STAFF REPORT TO Council SERVICE AREA Infrastructure, Development and Enterprise DATE November 18, 2015 SUBJECT Downtown Parking Master Plan (2016 to 2035) REPORT NUMBER IDE-BDE-1510 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PURPOSE OF REPORT To present the Parking Master Plan for approval. -

Restoring Dignity

Restoring Dignity Ontario Great Lakes Division Thrift Stores and Community & Family Services Two Day Conference Thursday September 20, 2012 Friday September 21, 2012 Guelph Citadel The Conference at-a-Glance Plan your day by choosing your sessions Thursday September 20, 2012 (Day 1) Leaders/Directors/Managers Day 8:00 am - 8:30 am Registration/Coffee 8:45 am - 9:00 am Welcome 9:00 am - Noon Session 1 (Choose A or B) A Health and Safety 101 B Tackling an Energy Crisis! Noon - 1:00 pm Lunch & Learn with Joanne Tilley, Regional Consultant, THQ Social Services 1:00 pm - 4:00 pm Session 2 (for all to attend) ALL Introducing Restorative Practice to Your Workplace Scheduled Breaks 10:45 to 11:00 am and 2:15 to 2:30 pm Friday September 21, 2012 (Day 2) Leaders/Directors/Managers PLUS bring a Front Line Staff 8:00 am - 8:30 am Registration/Coffee 8:45 am - 9:00 am Welcome 9:00 am - Noon Session 1 (Choose A or B) A Beyond Food Banks B Customer Service from the Inside Out Noon - 1:00 pm Lunch & Learn with Mike Couture, Ontario Great Lakes Divisional Support for Volunteer Services 1:00 pm - 4:00 pm Session 2 (Choose A or B) A Food Bank Round Table B Thrift Store Best Practices Scheduled Breaks 10:45 to 11:00 am and 2:15 to 2:30 pm Lunch & Learn Enjoy a ‘Lunch and Learn’ session with our Salvation Army Speakers Joanne Tilley Joanne is a Registered Nurse who has worked in acute health care for 20 years. -

How to Hillside Inside

7. What brought you to Hillside 8. How did you get to Hillside Inside? Inside? How to Hillside Inside The people who bring you Hillside Inside ● Event location ● I drove alone ● I carpooled Community Booths ● Scheduled performers ● I walked ● Guelph bus Inside Gate 5 · 3 to 9 pm Board of Directors Coordinators ● Event timing ● Other _________________ First of all, we would like to Open 3 pm to midnight Zack Benson, Accessibility: Menu Secretary Karen Calzonetti ● Brand/reputation of Hillside Welcome! Visit the community, thank you – our wonderful How to Hillside Inside Thunderheist Lisa Calzonetti Box Office On Site: Message from the Volunteer Manager ● Friends’ influence environmental and grassroots patrons – for your support was a dance- Feng’s Dumpling Nicholas Dalton Emily Kuberis floor hit at organizations, located inside of Dumplings – shrimp, s Hillside Inside brings together of our outstanding volunteers. ● Good value for dollar and enthusiasm. Hillside Adrian Harding, Coat Check: Hillside Inside friends, community and a rockin’ We truly couldn’t do this without ● Other _________________ Gate #5 in the Artisan Market, tofu-mushroom, ginger-beef .....6 for $5.00 Treasurer Tara Treanor Inside is unique, and we are 2009. to find out about their valuable ......................................... or 12 for $8.50 Sarah Mau, President Craft Vending: concert! you, and are so thankful for grateful for your continued Laura Harrison 9. Please rate the following event features on a scale of 1 -5 work. Rice Dim Sum ................................. $5.00 Jim Moon everyone’s dedication, commit- patronage. Dish in Zamboni: A big thank you goes out to all (1 = strongly disagree, 3 = neutral, and 5 = strongly agree). -

St. George's Square Conceptual Design

City of Guelph Downtown Streetscape Manual & Built Form Standards Section 4.0 St. George’s Square Conceptual Design July 2014 Table of Contents 4.1 Introduction Overview & Background 2 History & Evolution 3 Site Analysis 7 Strategic Assessment 11 Opportunities 13 Case Studies 15 4.2 Conceptual Design Guiding Principles 19 Objectives 20 St. George’s Square Concept Plan 21 Using the Plaza 29 Public Art 31 Design Guidelines 32 Impacts of Change 33 4.3 Implementation Implementation Overview 37 4.4 Appendix Auto Turn Analysis 41 4.1 Introduction c.1885 c.1902 St. George’s Square,c.1925 Circa 1885. St. George’s Square,c.1964 Circa 1902. St. George’s Square, Circa 1925. St. George’s Square, Circa 1964. 1 Conceptual Design Plan - St. George’s Square Overview & Background Conceptual Design Plan for St. George’s Square Introduction with the redesign and redevelopment of St. The Conceptual Design Plan for St. George’s George’s Square. The Conceptual Design outlines Square has been developed, in conjunction with six guiding principles, objectives of the Plan, a the updated Streetscape Design Manual and description of the concept, an illustrated plan Built Form Standards, to guide the redesign and and rendered perspective, design guidelines, and redevelopment of St. George’s Square. Section 4.1 a summary of resulting impacts on pedestrians, of this document provides an introduction which transit, traffic, and operations. considers the history and evolution of the Square, current patterns of daytime and evening use, the Implementation Strategy findings and recommendations of the Downtown Section 4.3 of this document provides an overview Strategic Assessment, other opportunities; and of the implementation strategy associated with lessons learned from recent and relevant case the redesign and redevelopment of St. -

Directions to the Wellington County Administration Centre from the West

Directions to the Wellington County Administration Centre (Human Resources Department) Walking/Drop-off The Human Resources Department can be found at the back of the Administration Centre on 74 Woolwich Street, Guelph. 1. Walk or drive through the alley between the Administration Centre (to the right) and the Sleeman Centre (to the left). You can be dropped off here. 2. Turn right towards the stairs. The first door to the left is the Human Resources Department. Parking The County of Wellington does not have visitor parking spots. There is free two hour parking on Woolwich Street, and on many downtown streets. However, these spots tend to go quickly, so do not rely on finding a free spot. We suggest leaving ample time to find parking. From the West Parkade 1. Park in the West Parkade located on MacDonell Street (left of the Co- operators building and Old Quebec Street Mall entrance). You will get a parking ticket if you park in the East Parkade. 2. Take the stairway exit going towards Quebec Street (Quebec Street Mall). 3. Take the elevator or stairs to the main floor. 4. Walk through the Old Quebec Street Mall and head towards the large staircase on your right (in front of Sports Hall of Fame) and turn left towards the hallway. 5. Go through the second pair of blue double doors (these lead outside). 6. At this point you will see the County Administration Building in front of you. The first door you will come to on the right hand side at the bottom of the stairs will be the Human Resources Department. -

HERITAGE GUELPH the Municipal Heritage Committee

HERITAGE GUELPH The Municipal Heritage Committee NOTICE OF MEETING A meeting of Heritage Guelph will be held at 12:00 Noon Monday January 8, 2007 GUELPH CITY HALL Committee Room C (Basement) A G E N D A 1. Approval of Agenda 2. Declarations of pecuniary interest 3. Approval of Minutes from the December 11, 2006 meeting. 4. Matters arising from the December 11, 2006 Minutes. 5. Business Items: a) Council / New Member Orientation -- dates / planning b) Turfgrass Institute -- member request to discuss heritage status. 1:00PM c) 264 Crawley Road -- request for Terms of Reference for Built Heritage Impact Assessment -- Owen Scott would like to discuss possibility of moving the Crawley Farmhouse and how to incorporate this into a BHIA 6. Information Items: a) Heritage Planner’s Update: Information provided as follow up to comments/resolutions passed by Heritage Guelph and preliminary inquiries. 11 Park update 806 Gordon update b) ACO/CHO/CAPHC Conference 2007 -- Update(Paul?) 7. Next Meeting: Monday January 22, 2007 Location: Council Committee Room C 8. Other matters introduced by the Chair or Heritage Guelph members. HERITAGE GUELPH The Municipal Heritage Committee NOTICE OF MEETING A meeting of Heritage Guelph will be held at 12:00 Noon Monday January 8, 2007 GUELPH CITY HALL Committee Room C (Basement) A G E N D A 1. Approval of Agenda 2. Declarations of pecuniary interest 3. Approval of Minutes from the December 11, 2006 meeting. 4. Matters arising from the December 11, 2006 Minutes. 5. Business Items: a) Council / New Member Orientation -- dates / planning b) Turfgrass Institute -- member request to discuss heritage status. -

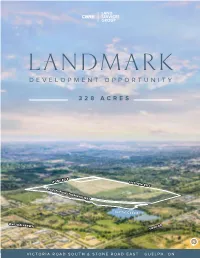

Development Opportunity

LANDMARK DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY ±328 ACRES STONE RD E VICTORIA RD S GUELPH JUNCTION RAILWAY CLYTH CREEK WATSON PRKWY S YORK RD VICTORIA ROAD SOUTH & STONE ROAD EAST · GUELPH, ON INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS CONSERVATION LANDS GU TURFGRASS LANDS (ARIO) EL PH JU CLYTH CREEK CLOSE PROXIMITY TO AMENITIES N C The offering is ideally located in close T proximity to the University of Guelph, I O the Downtown core and multiple transit FORMER WELLINGTON DETENTION N options, which all benefit the future uses CENTRE LANDS (MGCS) VICTORIA RD S R on-site. A I L W A Y SIGNIFICANT MIXED-USE STONE RD E DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY The policies designating the properties allows for the development of a compact mixed-use community that provides for a variety of employment and residential opportunities. Source:uoguelph.ca The Offering GUELPH LANDS INFORMATION DEVELOPMENT INCENTIVES The City of Guelph has a Brownfield On behalf of Infrastructure Ontario (“IO”) and the Agricultural Research Total Size 328.6 acres Redevelopment Community Improvement Institute of Ontario (“ARIO”), CBRE’s Land Services Group is pleased to offer Plan (CIP) to incent and stimulate 3,539 feet along Stone Rd E for sale the lands located at the northeast corner of Stone Road East and Frontage 4,832 feet along Victoria Rd S redevelopment of the area through potential Victoria Road South within the City of Guelph, on an as-is where is basis. tax and remediation assistance (TIBG) and The sites are located within the new Guelph Innovation District (“GID”) Official Plan OPA 54 an environmental study grant (ESG). Secondary Plan, known as OPA 54, designating the properties for a mix of UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH employment, residential, commercial and natural heritage uses. -

Fight Your Tickets: a Comprehensive Guide to Traffic Tickets” Has Been Freely Distributed and Contains the Key Sections of the fightyourtickets.Ca Website

About This Free Version This copy of “Fight Your Tickets: A Comprehensive Guide to Traffic Tickets” has been freely distributed and contains the key sections of the fightyourtickets.ca website. The complete eBook version has nine additional chapters that will help you win your traffic ticket, even without fighting it! The new chapters are: • I Just Want to Pay the Fine • Importance of Caselaw and Jurisprudence • Absolute and Strict Liability Offences • Defence of Necessity • Mandatory Time Limits for Laying Charges • Challenge a Speeding Ticket and Win • Laser Radar • How to Win a Ticket Without Fighting It • Pleadings and Motions Before the Court Thanks to our sponsors you can now get the complete eBook for FREE at: The complete and most current version of the eBook is also available for $19.99, from Smashwords.com, in the iBookstore for iPad, iPhone or iPod and as a PDF from the only website you’ll need to fight your traffic tickets! A paperback that contains the complete contents of the eBook is only $24.99 and can be purchased online at Amazon.com, Lulu.com or Federal Publications and in the Toronto area at select bookstores. Preview at Google Books. Praise for FightYourTickets.ca “After browsing through endless websites, I must say that your website has great step-by-step information to fight your own tickets. Thank you for all the work that you have put into this informational site!” – Julia N. “Your site is fantastic. I’m a student-at-law and I’m used to reading legal websites and your site is far and away one of the best I’ve seen.” – Ari S. -

UPCOMING EVENTS APRIL EVENT 24 Teams and Clubs – Photos

16 Old Brock Road, Puslinch, ON N0B 2J0 519-763-7040 @AberfoylePS 11 Zumba for Children’s Tumor foundation - $2 April showers will hopefully bring May flowers. With weather permitting Spring also comes thoughts of planting and warmer weather. 12 6:30 PM: School Council – Library 7:00 PM : Oratorical Contest – Zone Finals All the best, Paul Tribe, Principal 13 Assembly – Jump Rope for Heart Intermediate Floor Hockey Thank you Puslinch Optimists! 14 Good Friday We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the 17 Easter Monday Puslinch Optimist Club for donating $1000.00 to our school! Check out our article about the Oratorical 18 Talent Show Auditions – Primary competition later in the newsletter. Leadership Assembly – Grade 4 PD Days 2017 19 Gr. 7 Hep B; Gr. 7 girls HPV Blue Spruce voting – JK to Gr. 3 Please note for babysitting purposes that there is no school for students on the following days: 20 Colour Day • April 28th, Talent Show Auditions – Junior, Intermediate • June 9th, and 21 Scientist in School – gr. 5 • June 30th. Quebec Trip Third Payment Due Intermediate Spring Dance UPCOMING EVENTS APRIL EVENT 24 Teams and Clubs – Photos 03 PM - Primary Classes – Green Legacy 25 Focus on Nature – Gr. 5 all day Talent Show Auditions 04 Grade 2 - DASH Ms. Moldenhauer to Puslinch Library 05 AM – River Run – Ms. Singh, Ms. Moldenhauer, 26 River Run – Mr. Fiddes, Ms. Dinsmore, Ms. Ms. Robbers classes Bertrand Senior Luncheon – Ms. Singh, Ms. 1:30 PM - Music Night Rehearsal Moldenhauer, Ms. Robbers 5:00-8:00 PM – Parent Involvement Committee event – Centre Wellington DHS 06 UGDSB Chess Tournament – Puslinch Centre 27 Ms. -

Second Annual

second annual A mid-winter festival celebrating music & community in the heart of Guelph 1–11 pm Sleeman Centre Downtown Guelph • ADMISSION • Grandstand/floor: $60 schedule • 200 level tickets: $70 • Discounted tickets 1:00 pm · Main Stage for seniors (65+) and AboRIGINAL OPENING children (6-12): $55 CEREMONY (limited quantities) • Service charge extra. 1:05 pm · Island Stage GST included. Cash, THe d’URBERVILLES Visa, MC and debit. • Any remaining tickets 1:40 pm · Main Stage will be available at Gate GREAT LAKE #1. SWIMMERS • All tickets have access to the general admission 2:40 pm · Island Stage standing areas on the THE MAGIC floor, based on capacity. • No exchanges or 3:15 pm · Main Stage refunds. Hillside is not k’NAAN responsible for lost, 4:20 pm · Island Stage stolen, misplaced or unused tickets. JAY MALINOWSKI 4:55 pm · Main Stage • IMPORTANT BELL ORCHESTRE • Your wristband is your event pass. Do not 5:55 pm · Island Stage remove it! THUNDERHEIST • You will need both your ticket stub and your 6:40 pm · Main Stage wristband to get into the BEDOUIN SOUNDCLASH event. • Patrons are allowed 7:45 pm · Island Stage to come and go up to THAT 1 GUY 10:45 pm. No admission after 10:45 pm. 8:20 pm · Main Stage • No pets are allowed, SAM ROBERTS BAND with the exception of service dogs. 9:35 pm · Break • There are no facilities 10:00 pm · Main Stage or programming specifically for children. STARS Subject to change. Sleeman Centre event staff (yellow shirts) (yellow staff event Centre Sleeman (blackshirts) Hillside Insidevolunteers 1 2 3 4 -

Destination Canada ~ Tourism Ideas ~

Destination Canada ~ Tourism Ideas ~ Created by 2nd year BBRM students: Emily Reardon, Callie van Massenhoven, Jessica Toushan, Emma Hassall CONTENTS International Society for Equitation Science: ....................................................................................................... 3 Guelph 2019 ............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Cost Rating Legend ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Destinations Guelph ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Food .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Activities ................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Sights and Tours ................................................................................................................................................................ 10 Equine-Related Activities .............................................................................................................................................