A Look at Nature As Artifact and the Displacement of Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geoplanspring 2011

SPRING 2011 GEOPLAN DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY & PROGRAM IN PLANNING AND THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO ASSOCIATION OF GEOGRAPHY ALUMNI (UTAGA) Celebrating our 75th Anniversary he Department of Geography at the University of Toronto was founded in 1935 and the academic year 2010-11 was therefore our 75th anniversary. We had an excellent celebration, packed Twith events. It started early in September with a display at Robarts Library of more than 100 books authored by geography faculty and alumni. The display was seen by thousands of visitors to the library between September and October. We also put on a special departmen- tal speakers series with the theme of “Intersections” between human and physical geography and between geographers and the community. Twenty-two guest speakers participated and we held special panel sessions on the Tar Sands, Climate Change, the Aboriginal City, and Women and Factory Work in China. The biggest event of the year was a full weekend of activities in mid-September. The weekend began early on Thursday, September 16th, when the Planning Alumni Committee hosted its first Fall Plan- ning Mixer at the Duke of York, in honour of Geography’s 75th. On Friday afternoon, renowned climate change scholar Professor Diana Liverman (MA ‘80) from the University of Arizona gave a public lecture on “Governing Climate”. This was followed by an opening reception and book launch for Reflections on the History of Geography at the University of Toronto. On Saturday, there was a faculty panel ses- sion in the morning on the history of the department and a workshop exploring mapping on the web. -

OBSP Screening Site Locations (Wheelchair Accessible)

OBSP Screening Site Locations Provincial Toll-Free Number: 1-800-668-9304 Regional OBSP Centres: Greater Toronto North York Women’s Centre ËB (416) 512-0601 Area (G.T.A.): 100 Sheppard Avenue East, Suite 140 North York, Ontario M2N 6N5 Hamilton Sir William Osler Health Institute ËB (905) 389-0101 565 Sanatorium Road, Suite 207 Hamilton, Ontario L9C 7N4 Kingston 786 Blackburn Mews ËB (613) 384-4284 Kingston, Ontario 1 (800) 465-8850 K7P 2N7 Ottawa Hampton Park Plaza, 1419 Carling Ave. ËB (613) 728-0777 Suite 214 (2nd Floor), Ottawa, Ontario 1 (800) 465-6226 K1Z 7L6 Thunder Bay 984 Oliver Road, 4th Floor ËB (807) 684-7777 Thunder Bay, Ontario 1 (800) 461-7031 P7B 7C7 London 339 Talbot Street ËB (519) 432-0255 London, Ontario 1 (800) 461-0640 N6A 2R5 Windsor Walker Plaza 1200, ËB (519) 253-0903 1275 Walker Road, Unit 10 Windsor, Ontario N8Y 4X9 Sudbury 4 Walford Road ËB (705) 675-2283 Sudbury, Ontario 1 (800) 661-8897 P3E 2H4 Ë - Wheelchair accessible B – French Language Services Last revised: June 19, 2009 1 OBSP Affiliated Screening Sites: The OBSP Affiliated Screening Centres are listed here below according to the Local Health Information Network (LHIN) area they are located in. To determine which LHIN you reside in, go to the following website and enter your postal code: http://www.lhins.on.ca/FindYourLHIN.aspx, or Call the ministry INFO line at 1-888-779-7767 #1 Erie St. Clair LHIN City Site Name Address Booking Number Chatham Chatham-Kent Health Alliance, Chatham Campus ËB 80 Grand Avenue West (519) 437-6012 Chatham, ON N7L 1B7 Leamington -

Council Agenda

COUNCIL AGENDA Council Chambers, City Hall, 1 Carden Street DATE Wednesday, November 18, 2015 – 5:00 p.m. Please turn off or place on non-audible all cell phones, PDAs, Blackberrys and pagers during the meeting. Disclosure of Pecuniary Interest and General Nature Thereof Downtown Parking Master Plan Presentation • Peter Cartwright, General Manager, Business Development and Enterprise • Ian Panabaker, Manager, Downtown Renewal • Cameron Walsh, Project Director Recommendation 1. That Council receive report #IDE-BDE-1510, titled “Downtown Parking Master Plan”. 2. That staff be directed to implement Scenario #3 as described in report #IDE-BDE-1510. 3. That staff be directed to work with the Downtown Advisory Committee to develop metrics which will be used to measure and determine the effect and implementation of enhanced on-street parking management and customer service strategy within the downtown. 4. That staff be directed to implement a targeted community engagement process for the purpose of creating a periphery parking management system. 5. That staff be directed to provide annual progress reports regarding the implementation of the Parking Master Plan. 6. That staff be directed to explore and report back by Q2 2016 on current and alternative opportunities to maximize economies of scale/staging of downtown enterprise projects, beginning with the Wilson Street parkade and including analysis of available procurement methods that might advance innovative ways in delivering a quality designed and built structure(s). ADJOURNMENT Page 1 of 1 CITY OF GUELPH COUNCIL AGENDA STAFF REPORT TO Council SERVICE AREA Infrastructure, Development and Enterprise DATE November 18, 2015 SUBJECT Downtown Parking Master Plan (2016 to 2035) REPORT NUMBER IDE-BDE-1510 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PURPOSE OF REPORT To present the Parking Master Plan for approval. -

Restoring Dignity

Restoring Dignity Ontario Great Lakes Division Thrift Stores and Community & Family Services Two Day Conference Thursday September 20, 2012 Friday September 21, 2012 Guelph Citadel The Conference at-a-Glance Plan your day by choosing your sessions Thursday September 20, 2012 (Day 1) Leaders/Directors/Managers Day 8:00 am - 8:30 am Registration/Coffee 8:45 am - 9:00 am Welcome 9:00 am - Noon Session 1 (Choose A or B) A Health and Safety 101 B Tackling an Energy Crisis! Noon - 1:00 pm Lunch & Learn with Joanne Tilley, Regional Consultant, THQ Social Services 1:00 pm - 4:00 pm Session 2 (for all to attend) ALL Introducing Restorative Practice to Your Workplace Scheduled Breaks 10:45 to 11:00 am and 2:15 to 2:30 pm Friday September 21, 2012 (Day 2) Leaders/Directors/Managers PLUS bring a Front Line Staff 8:00 am - 8:30 am Registration/Coffee 8:45 am - 9:00 am Welcome 9:00 am - Noon Session 1 (Choose A or B) A Beyond Food Banks B Customer Service from the Inside Out Noon - 1:00 pm Lunch & Learn with Mike Couture, Ontario Great Lakes Divisional Support for Volunteer Services 1:00 pm - 4:00 pm Session 2 (Choose A or B) A Food Bank Round Table B Thrift Store Best Practices Scheduled Breaks 10:45 to 11:00 am and 2:15 to 2:30 pm Lunch & Learn Enjoy a ‘Lunch and Learn’ session with our Salvation Army Speakers Joanne Tilley Joanne is a Registered Nurse who has worked in acute health care for 20 years. -

14Th Annual Report the Canada Council 1970-1971

1 14th Annual Report The Canada Council 1970-1971 Honourable Gérard Pelletier Secretary of State of Canada Ottawa, Canada Sir, I have the honour to transmit herewith the Annual Report of the Canada Council, for submission to Parliament, as required by section 23 of the Canada Council Act (5-6 Elizabeth Ii, 1957, Chap. 3) for the fiscal year ending March 31, 1971. I am, Sir, Yours very truly, John G. Prentice, Chairman. June 341971 3 Contents The Arts The Humanities and Social Sciences Other Programs 10 Introduction 50 Levels of Subsidy, 1966-67 to 1970-71 90 Prizes and Special Awards 12 Levels of Subsidy, 1966-67 to 1970-71 51 Research Training 91 Cultural Exchanges Doctoral Fe//owships; distribution of 14 Music and Opera Doctoral Fellowships by discipline. 96 Canadian Commission for Unesco 21 Theatre 54 Research Work 100 Stanley House Leave Fellowships; distribution of Leave 27 Dance Fellowships by discipline; Research Finances Grants; distribution of Research Grants 102 Introduction 30 Visual Arts, Film and Photography by disciph’ne; list of Leave Fellowships, Killam Awards and large Research 105 Financial Statement 39 Writing Grants. Appendix 1 48 Other Grants 78 Research Communication 119 List of Doctoral Fellowships List of grants for publication, confer- ences, and travel to international Appendix 2 meetings. 125 List of Research Grants of less than $5,000 86 Special Grants Support of Learned Societies; Appendix 3 Other Assistance. 135 List of Securities March 31. 1971 Members John G. Prentice (Chairman) Brian Flemming Guy Rocher (Vice-Chairman) John M. Godfrey Ronald Baker Elizabeth A. Lane Jean-Charles Bonenfant Léon Lortie Alex Colville Byron March J. -

Architect Stanley M. Roscoe (1921-2010)

THEMATIC DOSSIER | DOSSIER THÉMATIQUE ARCHITECT STANLEY M. ROSCOE (1921-2010): PIONEERING INNOVATIONS Sharon VattaY is an architectural historian > SHARON VATTAY with wide-ranging professional and academic credentials. She holds a Ph.D. from the University of Toronto where she lectures on the history of architecture. She is also an associate at Goldsmith, Borgal & Company Ltd. Architects (GBCA)—a firm his paper traces the postwar archi- specializing in historic restoration and adaptive Ttectural designs of Stanley M. Roscoe reuse, with projects across Canada. Previous (1921-2010)—an architect who introduced cutting-edge construction techniques positions include Heritage planner at the City of and avant-garde styles to the mid-sized Hamilton, Ontario, and the City of Vaughan, Ontario. Canadian city of Hamilton, Ontario. While not necessarily radical in national or inter- national terms, Roscoe’s buildings were certainly progressive in the regional con- text of the day. As reported in a 1960 article on Roscoe in Time Magazine, his decade-long tenure as city architect brought to Hamilton “ten years of lively argument.”1 This spirited debate was the result of his role as a champion of modern design, within the traditional nineteenth- century Victorian city of Hamilton (fig. 1). The analysis of Roscoe’s oeuvre shows that, in the overall context of architec- ture in Canada, he was very much keep- ing pace with new developments and progress in building systems then being explored by architects across the coun- try. Not only did the writer of the afore- mentioned Time Magazine article boldly contend that Hamilton had received “the most interesting modern architecture in Canada” as a result of Roscoe’s employ- ment as their city architect,2 but a review of other references in the popular press, along with documents found in Roscoe’s personal correspondence,3 also uncovers many other accolades that support an assertion of the architect as a pioneer in modern architecture. -

How to Hillside Inside

7. What brought you to Hillside 8. How did you get to Hillside Inside? Inside? How to Hillside Inside The people who bring you Hillside Inside ● Event location ● I drove alone ● I carpooled Community Booths ● Scheduled performers ● I walked ● Guelph bus Inside Gate 5 · 3 to 9 pm Board of Directors Coordinators ● Event timing ● Other _________________ First of all, we would like to Open 3 pm to midnight Zack Benson, Accessibility: Menu Secretary Karen Calzonetti ● Brand/reputation of Hillside Welcome! Visit the community, thank you – our wonderful How to Hillside Inside Thunderheist Lisa Calzonetti Box Office On Site: Message from the Volunteer Manager ● Friends’ influence environmental and grassroots patrons – for your support was a dance- Feng’s Dumpling Nicholas Dalton Emily Kuberis floor hit at organizations, located inside of Dumplings – shrimp, s Hillside Inside brings together of our outstanding volunteers. ● Good value for dollar and enthusiasm. Hillside Adrian Harding, Coat Check: Hillside Inside friends, community and a rockin’ We truly couldn’t do this without ● Other _________________ Gate #5 in the Artisan Market, tofu-mushroom, ginger-beef .....6 for $5.00 Treasurer Tara Treanor Inside is unique, and we are 2009. to find out about their valuable ......................................... or 12 for $8.50 Sarah Mau, President Craft Vending: concert! you, and are so thankful for grateful for your continued Laura Harrison 9. Please rate the following event features on a scale of 1 -5 work. Rice Dim Sum ................................. $5.00 Jim Moon everyone’s dedication, commit- patronage. Dish in Zamboni: A big thank you goes out to all (1 = strongly disagree, 3 = neutral, and 5 = strongly agree). -

St. George's Square Conceptual Design

City of Guelph Downtown Streetscape Manual & Built Form Standards Section 4.0 St. George’s Square Conceptual Design July 2014 Table of Contents 4.1 Introduction Overview & Background 2 History & Evolution 3 Site Analysis 7 Strategic Assessment 11 Opportunities 13 Case Studies 15 4.2 Conceptual Design Guiding Principles 19 Objectives 20 St. George’s Square Concept Plan 21 Using the Plaza 29 Public Art 31 Design Guidelines 32 Impacts of Change 33 4.3 Implementation Implementation Overview 37 4.4 Appendix Auto Turn Analysis 41 4.1 Introduction c.1885 c.1902 St. George’s Square,c.1925 Circa 1885. St. George’s Square,c.1964 Circa 1902. St. George’s Square, Circa 1925. St. George’s Square, Circa 1964. 1 Conceptual Design Plan - St. George’s Square Overview & Background Conceptual Design Plan for St. George’s Square Introduction with the redesign and redevelopment of St. The Conceptual Design Plan for St. George’s George’s Square. The Conceptual Design outlines Square has been developed, in conjunction with six guiding principles, objectives of the Plan, a the updated Streetscape Design Manual and description of the concept, an illustrated plan Built Form Standards, to guide the redesign and and rendered perspective, design guidelines, and redevelopment of St. George’s Square. Section 4.1 a summary of resulting impacts on pedestrians, of this document provides an introduction which transit, traffic, and operations. considers the history and evolution of the Square, current patterns of daytime and evening use, the Implementation Strategy findings and recommendations of the Downtown Section 4.3 of this document provides an overview Strategic Assessment, other opportunities; and of the implementation strategy associated with lessons learned from recent and relevant case the redesign and redevelopment of St. -

Directions to the Wellington County Administration Centre from the West

Directions to the Wellington County Administration Centre (Human Resources Department) Walking/Drop-off The Human Resources Department can be found at the back of the Administration Centre on 74 Woolwich Street, Guelph. 1. Walk or drive through the alley between the Administration Centre (to the right) and the Sleeman Centre (to the left). You can be dropped off here. 2. Turn right towards the stairs. The first door to the left is the Human Resources Department. Parking The County of Wellington does not have visitor parking spots. There is free two hour parking on Woolwich Street, and on many downtown streets. However, these spots tend to go quickly, so do not rely on finding a free spot. We suggest leaving ample time to find parking. From the West Parkade 1. Park in the West Parkade located on MacDonell Street (left of the Co- operators building and Old Quebec Street Mall entrance). You will get a parking ticket if you park in the East Parkade. 2. Take the stairway exit going towards Quebec Street (Quebec Street Mall). 3. Take the elevator or stairs to the main floor. 4. Walk through the Old Quebec Street Mall and head towards the large staircase on your right (in front of Sports Hall of Fame) and turn left towards the hallway. 5. Go through the second pair of blue double doors (these lead outside). 6. At this point you will see the County Administration Building in front of you. The first door you will come to on the right hand side at the bottom of the stairs will be the Human Resources Department. -

HERITAGE GUELPH the Municipal Heritage Committee

HERITAGE GUELPH The Municipal Heritage Committee NOTICE OF MEETING A meeting of Heritage Guelph will be held at 12:00 Noon Monday January 8, 2007 GUELPH CITY HALL Committee Room C (Basement) A G E N D A 1. Approval of Agenda 2. Declarations of pecuniary interest 3. Approval of Minutes from the December 11, 2006 meeting. 4. Matters arising from the December 11, 2006 Minutes. 5. Business Items: a) Council / New Member Orientation -- dates / planning b) Turfgrass Institute -- member request to discuss heritage status. 1:00PM c) 264 Crawley Road -- request for Terms of Reference for Built Heritage Impact Assessment -- Owen Scott would like to discuss possibility of moving the Crawley Farmhouse and how to incorporate this into a BHIA 6. Information Items: a) Heritage Planner’s Update: Information provided as follow up to comments/resolutions passed by Heritage Guelph and preliminary inquiries. 11 Park update 806 Gordon update b) ACO/CHO/CAPHC Conference 2007 -- Update(Paul?) 7. Next Meeting: Monday January 22, 2007 Location: Council Committee Room C 8. Other matters introduced by the Chair or Heritage Guelph members. HERITAGE GUELPH The Municipal Heritage Committee NOTICE OF MEETING A meeting of Heritage Guelph will be held at 12:00 Noon Monday January 8, 2007 GUELPH CITY HALL Committee Room C (Basement) A G E N D A 1. Approval of Agenda 2. Declarations of pecuniary interest 3. Approval of Minutes from the December 11, 2006 meeting. 4. Matters arising from the December 11, 2006 Minutes. 5. Business Items: a) Council / New Member Orientation -- dates / planning b) Turfgrass Institute -- member request to discuss heritage status. -

Reimagine Victoriaville Study

Executive Summary Urban Systems Ltd, in partnership with Public City Architecture, Three Sixty Collective, and Menic Planning Services, were retained by the City of Thunder Bay to identify and evaluate development options for Victoriaville Centre. The Project Team consists of urban planners, architects and landscape architects, structural and civil engineers, land economists, and retail experts. The development options that were evaluated included: Revitalizing Victoriaville Centre as a retail destination; Repurposing Victoriaville Centre to provide community activities rather than retail activity; Demolishing the Victoria Avenue component of Victoriaville Centre and redeveloping the remaining portion with new food and retail options; and, Demolishing Victoriaville Centre in its entirety in order to re-establish Victoria Avenue and create new public spaces in the Syndicate Avenue right-of-way. Public engagement included open houses held at Victoriaville Centre in October 2019 and February 2020. The first open house asked citizens for their vision of what downtown Fort William could become. The second open house asked citizens to comment on four redevelopment options. Both engagement events were accompanied by surveys available for citizens to complete either in-person or online. Both in-person and online public engagement events were well-attended and well-utilized, reflecting the high level of public interest in the topic as well as the ease and accessibility of in-person and online events. The Project Team identified a preferred option based on a combination of quantitative data (for example capital and operating costs) and qualitative data (such as providing the greatest benefit to the downtown community) identified by the City of Thunder Bay. -

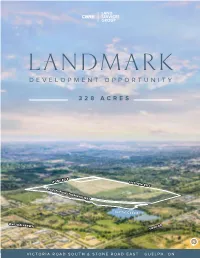

Development Opportunity

LANDMARK DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY ±328 ACRES STONE RD E VICTORIA RD S GUELPH JUNCTION RAILWAY CLYTH CREEK WATSON PRKWY S YORK RD VICTORIA ROAD SOUTH & STONE ROAD EAST · GUELPH, ON INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS CONSERVATION LANDS GU TURFGRASS LANDS (ARIO) EL PH JU CLYTH CREEK CLOSE PROXIMITY TO AMENITIES N C The offering is ideally located in close T proximity to the University of Guelph, I O the Downtown core and multiple transit FORMER WELLINGTON DETENTION N options, which all benefit the future uses CENTRE LANDS (MGCS) VICTORIA RD S R on-site. A I L W A Y SIGNIFICANT MIXED-USE STONE RD E DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY The policies designating the properties allows for the development of a compact mixed-use community that provides for a variety of employment and residential opportunities. Source:uoguelph.ca The Offering GUELPH LANDS INFORMATION DEVELOPMENT INCENTIVES The City of Guelph has a Brownfield On behalf of Infrastructure Ontario (“IO”) and the Agricultural Research Total Size 328.6 acres Redevelopment Community Improvement Institute of Ontario (“ARIO”), CBRE’s Land Services Group is pleased to offer Plan (CIP) to incent and stimulate 3,539 feet along Stone Rd E for sale the lands located at the northeast corner of Stone Road East and Frontage 4,832 feet along Victoria Rd S redevelopment of the area through potential Victoria Road South within the City of Guelph, on an as-is where is basis. tax and remediation assistance (TIBG) and The sites are located within the new Guelph Innovation District (“GID”) Official Plan OPA 54 an environmental study grant (ESG). Secondary Plan, known as OPA 54, designating the properties for a mix of UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH employment, residential, commercial and natural heritage uses.