Introduction to Viral Vector Safety Amanda Haley, Ph.D., RBP, MRSB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile Genetic Elements in Streptococci

Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. (2019) 32: 123-166. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21775/cimb.032.123 Mobile Genetic Elements in Streptococci Miao Lu#, Tao Gong#, Anqi Zhang, Boyu Tang, Jiamin Chen, Zhong Zhang, Yuqing Li*, Xuedong Zhou* State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, PR China. #Miao Lu and Tao Gong contributed equally to this work. *Address correspondence to: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Streptococci are a group of Gram-positive bacteria belonging to the family Streptococcaceae, which are responsible of multiple diseases. Some of these species can cause invasive infection that may result in life-threatening illness. Moreover, antibiotic-resistant bacteria are considerably increasing, thus imposing a global consideration. One of the main causes of this resistance is the horizontal gene transfer (HGT), associated to gene transfer agents including transposons, integrons, plasmids and bacteriophages. These agents, which are called mobile genetic elements (MGEs), encode proteins able to mediate DNA movements. This review briefly describes MGEs in streptococci, focusing on their structure and properties related to HGT and antibiotic resistance. caister.com/cimb 123 Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. (2019) Vol. 32 Mobile Genetic Elements Lu et al Introduction Streptococci are a group of Gram-positive bacteria widely distributed across human and animals. Unlike the Staphylococcus species, streptococci are catalase negative and are subclassified into the three subspecies alpha, beta and gamma according to the partial, complete or absent hemolysis induced, respectively. The beta hemolytic streptococci species are further classified by the cell wall carbohydrate composition (Lancefield, 1933) and according to human diseases in Lancefield groups A, B, C and G. -

Gutless Adenovirus: Last-Generation Adenovirus for Gene Therapy

Gene Therapy (2005) 12, S18–S27 & 2005 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0969-7128/05 $30.00 www.nature.com/gt CONFERENCE PAPER Gutless adenovirus: last-generation adenovirus for gene therapy R Alba1, A Bosch1 and M Chillon1,2 1Gene Therapy Laboratory, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Center of Animal Biotechnology and Gene Therapy (CBATEG), Universitat Auto`noma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Spain; and 2Institut Catala` de Recerca i Estudis Avanc¸ats (ICREA), Barcelona, Spain Last-generation adenovirus vectors, also called helper-depen- viral coding regions, gutless vectors require viral proteins dent or gutless adenovirus, are very attractive for gene therapy supplied in trans by a helper virus. To remove contamination because the associated in vivo immune response is highly by a helper virus from the final preparation, different systems reduced compared to first- and second-generation adenovirus based on the excision of the helper-packaging signal have vectors, while maintaining high transduction efficiency and been generated. Among them, Cre-loxP system is mostly tropism. Nowadays, gutless adenovirus is administered in used, although contamination levels still are 0.1–1% too high different organs, such as the liver, muscle or the central to be used in clinical trials. Recently developed strategies to nervous system achieving high-level and long-term transgene avoid/reduce helper contamination were reviewed. expression in rodents and primates. However, as devoid of all Gene Therapy (2005) 12, S18–S27. doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3302612 Keywords: adenovirus; gutless; helper-dependent vectors; in vivo gene therapy Introduction clinical for more information). Nowadays, adenovirus vectors are applied to treat cancer, monogenic disorders, Gene therapy for most genetic diseases requires expres- vascular diseases and others complications. -

Viral Vectors and Biological Safety

Viral Vectors and Biological Safety Viral vectors are often designed so that they can enter human cells and deliver genes of interest. Viral vectors are usually replication-deficient – genes necessary for replication of the virus are removed from the vector and supplied separately through plasmids, helper virus, or packaging cell lines. There are several biosafety concerns that arise with the use of viral vectors including: 1) Tropism (host range) – viral vectors that can enter (infect) human cells are often used. 2) Replication-deficient viral vectors can gain back the deleted genes required for replication (become replication-competent) through recombination – referred to as replication-competent virus (RCV) breakthroughs. 3) Genes may be expressed in tissues and/or organisms where they are normally not expressed. In the case of some genes such as oncogenes, this could have far-reaching negative consequences. When evaluating safety for use of viral vectors, a number of factors need to be considered including: Risk Group (RG) of the organism; tropism (organism and tissue); route of transmission; whether the virus integrates into the host genome; and the specific gene(s) being introduced. Please contact the Office of Biological Safety (OBS) for more information on physical barriers and safety practices to use with specific viral vectors. This article concentrates on biological barriers that can be employed to improve safety when using viral vectors. Viral vectors frequently used are: • Retrovirus/lentivirus • Adenovirus • Adeno-associated virus (AAV) • Poxvirus • Herpes virus • Alphavirus • Baculovirus Amphotropic murine leukemia virus (MLV) – also called Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) – and adenovirus are common viral vectors used to introduce genes into human cells. -

Neutralizing Antibody Against SARS-Cov-2 Spike in COVID-19 Patients, Health Care Workers, and Convalescent Plasma Donors

TECHNICAL ADVANCE Neutralizing antibody against SARS-CoV-2 spike in COVID-19 patients, health care workers, and convalescent plasma donors Cong Zeng,1,2 John P. Evans,1,2,3 Rebecca Pearson,4 Panke Qu,1,2 Yi-Min Zheng,1,2 Richard T. Robinson,5 Luanne Hall-Stoodley,5 Jacob Yount,5 Sonal Pannu,6 Rama K. Mallampalli,6 Linda Saif,7,8 Eugene Oltz,5 Gerard Lozanski,4 and Shan-Lu Liu1,2,5,8 1Center for Retrovirus Research, 2Department of Veterinary Biosciences, 3Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology Program, 4Department of Pathology, 5Department of Microbial Infection and Immunity, and 6Department of Medicine, The Ohio State University (OSU), Columbus, Ohio, USA. 7Food Animal Health Research Program, Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, Wooster, Ohio, USA. 8Viruses and Emerging Pathogens Program, Infectious Diseases Institute, OSU, Columbus, Ohio, USA. Rapid and specific antibody testing is crucial for improved understanding, control, and treatment of COVID-19 pathogenesis. Herein, we describe and apply a rapid, sensitive, and accurate virus neutralization assay for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. The assay is based on an HIV-1 lentiviral vector that contains a secreted intron Gaussia luciferase (Gluc) or secreted nano-luciferase reporter cassette, pseudotyped with the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) glycoprotein, and is validated with a plaque-reduction assay using an authentic, infectious SARS-CoV-2 strain. The assay was used to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in serum from individuals with a broad range of COVID-19 symptoms; patients included those in the intensive care unit (ICU), health care workers (HCWs), and convalescent plasma donors. -

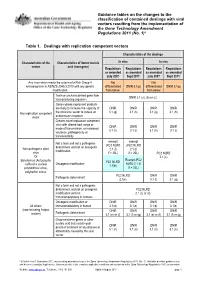

Guidance Tables on the Changes To

Guidance tables on the changes to the classification of contained dealings with viral vectors resulting from the implementation of the Gene Technology Amendment Regulations 2011 (No. 1)* Table 1. Dealings with replication competent vectors Characteristics of the dealings Characteristics of the Characteristics of donor nucleic In vitro In vivo vector acid (transgene) Regulations Regulations Regulations Regulations as amended as amended as amended as amended July 2007 Sept 2011* July 2007 Sept 2011* Any virus which meets the criteria of a Risk Group 4 Not Not microorganism in AS/NZS 2243.3:2010 with any genetic differentiated DNIR 3.1(p) differentiated DNIR 3.1(p) modification from below from below Toxin or uncharacterised gene from DNIR 3.1 (a), (b) or (c) toxin producing organism Genes whose expressed products are likely to increase the capacity of DNIR DNIR DNIR DNIR Any replication competent the virus/viral vector to induce an 3.1 (g) 3.1 (h) 3.1 (g) 3.1 (h) vector autoimmune response Creates novel replication competent virus with altered host range or DNIR DNIR DNIR DNIR mode of transmission, or increased 3.1 (h) 3.1 (i) 3.1 (h) 3.1 (i) virulence, pathogenicity or transmissibility exempt exempt Not a toxin and not a pathogenic (PC2 NLRD (PC2 NLRD determinant and not an oncogenic Non-pathogenic plant 2.1 (f) 2.1 (f) modification virus if > 25L) if > 25L) PC2 NLRD Or 2.1 (c) Exempt (PC2 Baculovirus (Autographa PC1 NLRD Oncogenic modification NLRD 2.1 (f) californica nuclear 1.1(b) polyhedrosis virus), if > 25L) polyhedrin minus PC2 NLRD -

SARS-Cov-2 RBD Antibodies That Maximize Breadth and Resistance to Escape W 1,15 2,15 3,15 4 Tyler N

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03807-6 Accelerated Article Preview SARS-CoV-2 RBD antibodies that maximize W breadth and resistance to escape E VI Received: 29 March 2021 Tyler N. Starr, N ad in e Czudnochowski, Zhuoming Liu, Fabrizia Zatta, Young-Jun Park, Amin Addetia, Dora Pinto, Martina Beltramello, Patrick Hernandez, AllisonE J. Greaney, Accepted: 6 July 2021 Roberta Marzi, William G. Glass, Ivy Zhang, Adam S. Dingens, John E. B ow en, Accelerated Article Preview Published M . Alejandra Tortorici, Alexandra C. W al ls , J as on A. Wojcechowskyj,R Anna De Marco, online 14 July 2021 Laura E. Rosen, Jiayi Zhou, Martin Montiel-Ruiz, Hannah Kaiser, Josh Dillen, Heather Tucker, Jessica Bassi, Chiara Silacci-Fregni, Michael P. Housley,P Julia di Iulio, Gloria Lombardo, Cite this article as: Starr, T. N. et al. Maria Agostini, Nicole Sprugasci, Katja Culap, Stefano Jaconi, Marcel Meury, SARS-CoV-2 RBD antibodies that maximize Exequiel Dellota, Rana Abdelnabi, Shi-Yan Caroline Foo, Elisabetta Cameroni, breadth and resistance to escape. Nature Spencer Stumpf, Tristan I. Croll, Jay C. Nix, ColinE Havenar-Daughton, Luca Piccoli, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03807-6 Fabio Benigni, Johan Neyts, Amalio Telenti, Florian A. Lempp, Matteo S. Pizzuto, (2021). John D. Chodera, Christy M. Hebner, HerbertL W. Virgin, Sean P. J. Whelan, David Veesler, Davide Corti, Jesse D. Bloom & Gyorgy Snell I C This is a PDF fle of a peer-reviewed paper that has been accepted for publication. Although unedited, the Tcontent has been subjected to preliminary formatting. Nature is providing this earlyR version of the typeset paper as a service to our authors and readers. -

Spread of a SARS-Cov-2 Variant Through Europe in the Summer of 2020

Article Spread of a SARS-CoV-2 variant through Europe in the summer of 2020 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03677-y Emma B. Hodcroft1,2,3 ✉, Moira Zuber1, Sarah Nadeau2,4, Timothy G. Vaughan2,4, Katharine H. D. Crawford5,6,7, Christian L. Althaus3, Martina L. Reichmuth3, John E. Bowen8, Received: 25 November 2020 Alexandra C. Walls8, Davide Corti9, Jesse D. Bloom5,6,10, David Veesler8, David Mateo11, Accepted: 28 May 2021 Alberto Hernando11, Iñaki Comas12,13, Fernando González-Candelas13,14, SeqCOVID-SPAIN consortium*, Tanja Stadler2,4,92 & Richard A. Neher1,2,92 ✉ Published online: 7 June 2021 Check for updates Following its emergence in late 2019, the spread of SARS-CoV-21,2 has been tracked by phylogenetic analysis of viral genome sequences in unprecedented detail3–5. Although the virus spread globally in early 2020 before borders closed, intercontinental travel has since been greatly reduced. However, travel within Europe resumed in the summer of 2020. Here we report on a SARS-CoV-2 variant, 20E (EU1), that was identifed in Spain in early summer 2020 and subsequently spread across Europe. We fnd no evidence that this variant has increased transmissibility, but instead demonstrate how rising incidence in Spain, resumption of travel, and lack of efective screening and containment may explain the variant’s success. Despite travel restrictions, we estimate that 20E (EU1) was introduced hundreds of times to European countries by summertime travellers, which is likely to have undermined local eforts to minimize infection with SARS-CoV-2. Our results illustrate how a variant can rapidly become dominant even in the absence of a substantial transmission advantage in favourable epidemiological settings. -

Protocol and Reagents for Pseudotyping Lentiviral Particles with SARS-Cov-2 Spike Protein for Neutralization Assays

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.20.051219; this version posted April 20, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 of 15 Protocol and reagents for pseudotyping lentiviral particles with SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein for neutralization assays Katharine H.D. Crawford 1,2,3, Rachel Eguia 1, Adam S. Dingens 1, Andrea N. Loes 1, Keara D. Malone 1, Caitlin R. Wolf 4, Helen Y. Chu 4, M. Alejandra Tortorici 5,6, David Veesler 5, Michael Murphy 7, Deleah Pettie 7, Neil P. King 5,7, Alejandro B. Balazs 8, and Jesse D. Bloom 1,2,9,* 1 Division of Basic Sciences and Computational Biology Program, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA 98109, USA; [email protected] (K.D.C.), [email protected] (R.E.), [email protected] (A.S.D.), [email protected] (K.M.), [email protected] (A.N.L.) 2 Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA 3 Medical Scientist Training Program, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA 4 Division of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA; [email protected] (C.R.W.), [email protected] (H.Y.C.) 5 Department of Biochemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98109, USA; [email protected] (M.A.T.), [email protected] (D.V.), [email protected] (M.M.), [email protected] (D.P.), [email protected] (N.P.K.) 6 Institute -

Viral Vectors

OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH CONSIDERATIONS FOR WORK WITH LENTIVIRAL VECTORS GARY R. FUJIMOTO, M.D. OCCUPATIONAL MEDICINE CONSULTANT OCTOBER 6, 2014 Disclosure: Lecture includes off-label use of antiretroviral medications VIRAL VECTORS Definition: Viruses engineered to deliver foreign genetic material (transgene) to cells Many viral vectors deliver the genetic material into the host cells but not into the host genome where the virus replicates (unless replication incompetent) Retroviral and lentiviral vectors deliver genetic transgenes into the host chromosomes LENTIVIRAL VECTORS Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a lentivirus that infects both dividing and non-dividing cells Use of the HIV virus as a viral vector has required the reengineering of the virus to achieve safe gene transfer Since HIV normally targets CD4 cells, replacing the HIV envelope gene with vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G) expands the infectious range of the vector and modes of transmission LENTIVIRAL VECTORS Remember: replication deficient lentiviral vectors integrate the vector into the host chromosomes 3rd and 4th generation constructs unlikely to become replication competent with enhanced safety due to self- inactivating vectors (however, consider present or future HIV infection) Replication deficient lentiviral vectors should be regarded as single-event infectious agents Many researchers regard these agents as relatively benign although transgene integration does occur with generally unknown effects LENTIVIRAL OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURES Lentiviral -

Enhanced Pseudotyping Efficiency of HIV-1 Lentiviral Vectors by A

Gene Therapy (2012) 19, 761–774 & 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0969-7128/12 www.nature.com/gt ORIGINAL ARTICLE Enhanced pseudotyping efficiency of HIV-1 lentiviral vectors by a rabies/vesicular stomatitis virus chimeric envelope glycoprotein DCJ Carpentier, K Vevis1, A Trabalza, C Georgiadis, SM Ellison, RI Asfahani2 and ND Mazarakis Rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG) can pseudotype lentiviral vectors, although at a lower efficiency to that of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSVG). Transduction with VSVG-pseudotyped vectors of rodent central nervous system (CNS) leads to local neurotropic gene transfer, whereas with RVG-pseudotyped vectors additional disperse transduction of neurons located at distal efferent sites occurs via axonal retrograde transport. Attempts to produce high-titre RVG-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors for preclinical and clinical trials has to date been problematic. We have constructed several chimeric RVG/VSVG glycoproteins and found that a construct bearing the external/transmembrane domain of RVG and the cytoplasmic domain of VSVG shows increased incorporation onto HIV-1 lentiviral particles and has increased infectivity in vitro in 293T cells and in differentiated neuronal cell lines of human, rat and murine origin. Stereotactic application of vector pseudotyped with this RVG/VSVG chimera in the rat striatum resulted in efficient gene transfer at the site of injection showing both neuronal and glial tropism. Distal neuronal transduction in the substantia nigra, thalamus and olfactory bulb via retrograde axonal transport also occurs after intrastriatal administration of chimera-pseudotyped vectors at similar levels to that observed with a RVG-pseudotyped vector. This is the first report of distal transduction in the olfactory bulb. -

Viral Vectors

505 Oldham Court Lexington, KY 40502 Phone: (859) 257-1049 Fax: (859) 323-3838 E-Mail: [email protected] http://ehs.uky.edu/biosafety VIRAL VECTORS WHAT IS A VIRAL VECTOR? Viral vectors work like a “nanosyringe” to deliver nucleic acid to a target. They are often more efficient than other transfection methods, are useful for whole organism studies, have a relatively low toxicity, and are a likely route for human gene transfer. All viral vectors require a host for replication. The production of a viral vector is typically separated from the ability of the viral vector to infect cells. While viral vectors are not typically considered infectious agents, they do maintain their ability to “infect” cells. Viral vectors just don’t replicate (although there are some replicating viral vectors in use) under experimental conditions. An HIV- based lentiviral vector no longer possesses the ability to infect an individual with HIV, but it does maintain the ability to enter a cell and express genetic information. This is why viral vectors are useful, but also require caution. If a viral vector can transfect a human cell line on a plate, it can also transfect YOUR cells if accidentally exposed. SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS FOR ALL VIRAL VECTORS When utilizing ANY viral vector, the following questions must be addressed… 1. What potential does your method of viral vector production have to generate a replication competent virus? a. Generation of viral vector refers to the number of recombination events required to form a replication competent virus. For example, if you’re using a lentivirus that is split up between 4 plasmids (gag/pol, VSV-g, rev, transgene), 3 recombination events must take place to create a replication competent virus, therefore you are using a 3rd generation lentiviral vector. -

RNA Viruses As Tools in Gene Therapy and Vaccine Development

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review RNA Viruses as Tools in Gene Therapy and Vaccine Development Kenneth Lundstrom PanTherapeutics, Rte de Lavaux 49, CH1095 Lutry, Switzerland; [email protected]; Tel.: +41-79-776-6351 Received: 31 January 2019; Accepted: 21 February 2019; Published: 1 March 2019 Abstract: RNA viruses have been subjected to substantial engineering efforts to support gene therapy applications and vaccine development. Typically, retroviruses, lentiviruses, alphaviruses, flaviviruses rhabdoviruses, measles viruses, Newcastle disease viruses, and picornaviruses have been employed as expression vectors for treatment of various diseases including different types of cancers, hemophilia, and infectious diseases. Moreover, vaccination with viral vectors has evaluated immunogenicity against infectious agents and protection against challenges with pathogenic organisms. Several preclinical studies in animal models have confirmed both immune responses and protection against lethal challenges. Similarly, administration of RNA viral vectors in animals implanted with tumor xenografts resulted in tumor regression and prolonged survival, and in some cases complete tumor clearance. Based on preclinical results, clinical trials have been conducted to establish the safety of RNA virus delivery. Moreover, stem cell-based lentiviral therapy provided life-long production of factor VIII potentially generating a cure for hemophilia A. Several clinical trials on cancer patients have generated anti-tumor activity, prolonged survival, and