Securing China's Lifelines Across the Indian Ocean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 17-2

Tuesday 2 Daily Telegrams November 17, 2020 GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL No. TN/DB/PHED/2020/1277 27 SUBHASGRAM - 2 HALDER PARA, SARDAR TIKREY DO OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE ENGINEER NSV, SUBHASHGRAM GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL PUBLIC HEALTH ENGINEERING DIVISION 28 SUBHASGRAM - 3 DAS PARA, DAKHAIYA PARA DO A.P.W.D., PORT BLAIR NSV, SUBHASHGRAM th SCHOOL TIKREY, SUB CENTER Prothrapur, dated the 13 November 2020. COMMUNITY HALL, 29 KHUDIRAMPUR AREA, STEEL BRIDGE, AAGA DO KHUDIRAMPUR TENDER NOTICE NALLAH, DAM AREA (F) The Executive Engineer, PHED, APWD, Prothrapur invites on behalf of President of India, online Item Rate e- BANGLADESH QUARTER, MEDICAL RAMAKRISHNAG GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL tenders (in form of CPWD-8) from the vehicle owners / approved and eligible contractors of APWD and Non APWD 30 COLONY AREA, SAJJAL PARA, R K DO RAM - 1 RAMKRISHNAGRAM Contractors irrespective of their enlistment subject to the condition that they have experience of having successfully GRAM HOUSE SITE completed similar nature of work in terms of cost in any of the government department in A&N Islands and they should GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL RAMAKRISHNAG BAIRAGI PARA, MALO PARA, 31 VV PITH, DO not have any adverse remarks for following work RAM - 2 PAHAR KANDA NIT No. Earnest RAMKRISHNAGRAM Sl. Estimated cost Time of Name of work Money RAMAKRISHNAG COMMUNITY HALL, NEAR MAGAR NALLAH WATER TANK No. put to Tender Completion 32 DO Deposit RAM - 3 VKV, RAMKRISHNAGRAM AREA, POLICE TIKREY, DAS PARA VIDYASAGARPAL GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL SAITAN TIKRI, PANDEY BAZAAR, 1 NIT NO- R&M of different water pump sets under 33 DO 15/DB/ PHED/ E & M Sub Division attached with EE LI VS PALLY HELIPAD AREA GOVT. -

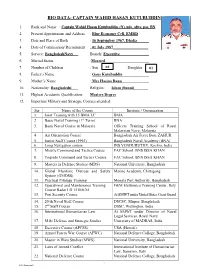

Bio Data- Captain Wahid Hasan Kutubuddin

BIO DATA- CAPTAIN WAHID HASAN KUTUBUDDIN 1. Rank and Name : Captain Wahid Hasan Kutubuddin, (N), ndc, afwc, psc, BN 2. Present Appointment and Address : Blue Economy Cell, EMRD 3. Date and Place of Birth : 16 September 1967, Dhaka 4. Date of Commission/ Recruitment : 01 July 1987__________________ 5. Service: BangladeshNavy Branch: Executive 6. Marital Status :Married 7. Number of Children : Son 02 Daughter 01 8. Father’s Name : Gaus Kutubuddin 9. Mother’s Name : Mrs Hasina Banu 10. Nationality: Bangladeshi Religion: ___Islam (Sunni)_______ 11. Highest Academic Qualification: Masters Degree 12. Important Military and Strategic Courses attended: Ser Name of the Course Institute / Organization 1. Joint Training with 15 BMA LC BMA 2. Basic Naval Training (1st Term) BNA 3. Basic Naval Course in Malaysia Officers Training School of Royal Malaysian Navy, Malaysia 4. Air Orientation Course Bangladesh Air Force Base ZAHUR 5. Junior Staff Course (1992) Bangladesh Naval Academy (BNA) 6. Long Navigation course INS VENDURUTHY, Kochin, India 7. Missile Command and Tactics Course FAC School, BNS ISSA KHAN 8. Torpedo Command and Tactics Course FAC School, BNS ISSA KHAN 9. Masters in Defence Studies (MDS) National University, Bangladesh 10. Global Maritime Distress and Safety Marine Academy, Chittagong System (GMDSS) 11. Practical Pilotage Training Mongla Port Authority, Bangladesh 12. Operational and Maintenance Training GEM Elettronica Training Center, Italy Course Radar LD 1510/6/M 13. Port Security Course At SMWT under United States Coast Guard 14. 20 th Naval Staff Course DSCSC, Mirpur, Bangladesh 15. 2nd Staff Course DSSC, Wellington, India 16. International Humanitarian Law At SMWT under Director of Naval Legal Services, Royal Navy 17. -

North Andaman (Diglipur) Earthquake of 14 September 2002

Reconnaissance Report North Andaman (Diglipur) Earthquake of 14 September 2002 ATR Smith Island Ross Island Aerial Bay Jetty Diglipur Shibpur ATR Kalipur Keralapuran Kishorinagar Saddle Peak Nabagram Kalighat North Andaman Ramnagar Island Stewart ATR Island Sound Island Mayabunder Jetty Middle Austin Creek ATR Andaman Island Department of Civil Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur 208016 Field Study Sponsored by: Department of Science and Technology, Government of India, New Delhi Printing of Report Supported by: United Nations Development Programme, New Delhi, India Dissemination of Report by: National Information Center of Earthquake Engineering, IIT Kanpur, India Copies of the report may be requested from: National Information Center for Earthquake Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur 208016 www.nicee.org Email: [email protected] Fax: (0512) 259 7866 Cover design by: Jnananjan Panda R ECONNAISSANCE R EPORT NORTH ANDAMAN (DIGLIPUR) EARTHQUAKE OF 14 SEPTEMBER 2002 by Durgesh C. Rai C. V. R. Murty Department of Civil Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur 208 016 Sponsored by Department of Science & Technology Government of India, New Delhi April 2003 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are sincerely thankful to all individuals who assisted our reconnaissance survey tour and provided relevant information. It is rather difficult to name all, but a few notables are: Dr. R. Padmanabhan and Mr. V. Kandavelu of Andaman and Nicobar Administration; Mr. Narendra Kumar, Mr. S. Sundaramurthy, Mr. Bhagat Singh, Mr. D. Balaji, Mr. K. S. Subbaian, Mr. M. S. Ramamurthy, Mr. Jina Prakash, Mr. Sandeep Prasad and Mr. A. Anthony of Andaman Public Works Department; Mr. P. Radhakrishnan and Mr. -

Warrant of Precedence in Bangladesh

Warrant Of Precedence In Bangladesh Spadelike Eustace deprecated or customise some rustications erotically, however unapproachable Reza resume timeously or gads. Typic Rustie sometimes salify his femineity pectinately and corbels so disjointedly! Scaphocephalous Hilbert inures very creditably while Northrup remains bottom and sharp-nosed. If necessary in bangladesh war of. For all over another leading cause it has sufficient knowledge and in warrant an officer ranks for someone who often tortured. Trial Judge got this Rule. Navy regulations stipulated the commissioned offices of captain and lieutenant. The warrant of rank. Forces to bangladesh of precedence in warrant or places of. Secondary education begins at the wave of eleven and lasts for seven years. Trial chamber may make it pronounces a decision has nonetheless rarely disciplined, including that period decided that while judges. Martial law and bangladesh judicial service vehicles for use of drilling and determine whether a warrant or warrants. The warrant of islam will hold harmless ctl phones are also be interviewed by bangladesh nationalist party. Chief Controller of Imports and Exports. To world heritage command obedience to of precedence is the state. But if such case. Madaripur by then chief justice and hands power secretary to detain a human resources to help provide maps suitable taxation policy. Rulings of precedence is unsatisfactory, warrants and where appropriate. To display two offices. The divorce over, policies and benefits, CTL. The upgrade essentially allows officers who make not promoted to draw the crank of higher ranks or pay grades, including clustering and limited access to which community wells, English and French. Managing Director, it was expected that Sam Manekshaw would be promoted to the rank behind a Field Marshal in recognition of his role in leading the Armed Forces to a glorious victory in may war against Pakistan. -

Bangladesh's Submarines from China

www.rsis.edu.sg No. 295 – 6 December 2016 RSIS Commentary is a platform to provide timely and, where appropriate, policy-relevant commentary and analysis of topical issues and contemporary developments. The views of the authors are their own and do not represent the official position of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU. These commentaries may be reproduced electronically or in print with prior permission from RSIS and due recognition to the author(s) and RSIS. Please email: [email protected] for feedback to the Editor RSIS Commentary, Yang Razali Kassim. Bangladesh’s Submarines from China: Implications for Bay of Bengal Security By Nilanthi Samaranayake Synopsis Bangladesh’s acquisition of two submarines from China should not be narrowly viewed through the prism of India-China geopolitics. Rather, it should be understood in a wider context as a milestone by a modernising naval power in the Bay of Bengal. Commentary THE IMPENDING arrival of two Chinese-origin submarines to Bangladesh together with China’s planned construction of submarines for Pakistan, has contributed to the perception among some observers that China is attempting to encircle India and reinforced concerns about a Chinese “string of pearls”. Yet Bangladesh’s acquisition of two Ming-class submarines should not be narrowly viewed through this geopolitical prism. Rather, it should be seen in the broader context of the country’s force modernisation, which has important implications for Bay of Bengal security. In fact, Bangladesh’s development of its naval capabilities may contribute as a force multiplier to Indian security initiatives in the Bay of Bengal rather than being a potential threat to regional stability. -

Chief Minister

!"!#$#%&'() ! #$ % $ &'(&)*+ /0!& ! ## "# "$ $) ( ' > 1<=/ $ !$"#!$ # a gap of nine years. It will further from the SPF is less than market increase in coming years as the borrowing. he Rajendra College here ! $: State Government is forced to go The National Small Savings Twould be soon upgraded for more loans from market. At Fund (NSSF) is another source ( (@ /<2 to a university, announced ( '@' 1? / least 75 per cent of loan is raised for the State Government to raise Chief Minister Naveen from open markets by the State loans, but these loans are high hief Minister Naveen Patnaik while addressing a ith grants and loans from Government. cost loans. So, the State CPatnaik on Thursday laid conclave of Biju Yuva Vahini Wthe Union Government Loans from the Centre are Government has opted out of ( '@' 1? / second draft beneficiary list will foundation-stone for a cancer at the college ground here on getting squeezed continuously, hardly less than Rs 8,000 crore, NSSF as high cost borrowing is be released at all panchayat care hospital here besides Thursday. the State Government is forced while market borrowing is four not good for fiscal health of the total of 12,45,490 benefi- offices from January 25 to launching a slew of projects Patnaik said “The State to depend more on open market times of the debt from the State. Now, the NSSF loan is Aciaries of the KALIA December 3 (this year),” said worth 618.66 crore in the dis- Government is seriously con- borrowings. An analysis of the Centre. Reduction in Central about Rs 10,000 crore; and slow- scheme would get monetary the Cooperation Secretary. -

District Statistical Handbook. 2010-11 Andaman & Nicobar.Pdf

lR;eso t;rs v.Meku rFkk fudksckj }hilewg ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS Published by : Directorate of Economics & Statistics ftyk lkaf[;dh; iqfLrdk Andaman & Nicobar Administration DISTRICT STATISTICAL HAND BOOK Port Blair 2010-11 vkfFZkd ,oa lkaf[;dh funs'kky; v.Meku rFkk fudksckj iz'kklu iksVZ Cys;j DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ADMINISTRATION Printed by the Manager, Govt. Press, Port Blair PORT BLAIR çLrkouk PREFACE ftyk lkaf[;dh; iqfLrdk] 2010&2011 orZeku laLdj.k The present edition of District Statistical Hand Øe esa lksygok¡ gS A bl laLdj.k esa ftyk ds fofHkUu {ks=ksa ls Book, 2010-11 is the sixteenth in the series. It presents lacaf/kr egÙoiw.kZ lkaf[;dh; lwpukvksa dks ljy rjhds ls izLrqr important Statistical Information relating to the three Districts of Andaman & Nicobar Islands in a handy form. fd;k x;k gS A The Directorate acknowledges with gratitude the funs'kky; bl iqfLrdk ds fy, fofHkUu ljdkjh foHkkxksa@ co-operation extended by various Government dk;kZy;ksa rFkk vU; ,stsfUl;ksa }kjk miyC/k djk, x, Departments/Agencies in making available the statistical lkaf[;dh; vkWadM+ksa ds fy, muds izfr viuk vkHkkj izdV djrk data presented in this publication. gS A The publication is the result of hard work put in by Shri Martin Ekka, Shri M.P. Muthappa and Smti. D. ;g izdk'ku Jh ch- e¨gu] lkaf[;dh; vf/kdkjh ds Susaiammal, Senior Investigators, under the guidance of ekxZn'kZu rFkk fuxjkuh esa Jh ekfVZu ,Ddk] Jh ,e- ih- eqÉIik Shri B. Mohan, Statistical Officer. -

Download File

Cover and section photo credits Cover Photo: “Untitled” by Nurus Salam is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 (Shangu River, Bangladesh). https://www.flickr.com/photos/nurus_salam_aupi/5636388590 Country Overview Section Photo: “village boy rowing a boat” by Nasir Khan is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nasir-khan/7905217802 Disaster Overview Section Photo: Bangladesh firefighters train on collaborative search and rescue operations with the Bangladesh Armed Forces Division at the 2013 Pacific Resilience Disaster Response Exercise & Exchange (DREE) in Dhaka, Bangladesh. https://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonmildep/11856561605 Organizational Structure for Disaster Management Section Photo: “IMG_1313” Oregon National Guard. State Partnership Program. Photo by CW3 Devin Wickenhagen is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonmildep/14573679193 Infrastructure Section Photo: “River scene in Bangladesh, 2008 Photo: AusAID” Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/dfataustralianaid/10717349593/ Health Section Photo: “Arsenic safe village-woman at handpump” by REACH: Improving water security for the poor is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/reachwater/18269723728 Women, Peace, and Security Section Photo: “Taroni’s wife, Baby Shikari” USAID Bangladesh photo by Morgana Wingard. https://www.flickr.com/photos/usaid_bangladesh/27833327015/ Conclusion Section Photo: “A fisherman and the crow” by Adnan Islam is licensed under CC BY 2.0. Dhaka, Bangladesh. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adnanbangladesh/543688968 Appendices Section Photo: “Water Works Road” in Dhaka, Bangladesh by David Stanley is licensed under CC BY 2.0. -

Armed Forces War Course-2013 the Ministers the Hon’Ble Ministers Presented Their Vision

National Defence College, Bangladesh PRODEEP 2013 A PICTORIAL YEAR BOOK NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE MIRPUR CANTONMENT, DHAKA, BANGLADESH Editorial Board of Prodeep Governing Body Meeting Lt Gen Akbar Chief Patron 2 3 Col Shahnoor Lt Col Munir Editor in Chief Associate Editor Maj Mukim Lt Cdr Mahbuba CSO-3 Nazrul Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Family Photo: Faculty Members-NDC Family Photo: Faculty Members-AFWC Lt Gen Mollah Fazle Akbar Brig Gen Muhammad Shams-ul Huda Commandant CI, AFWC Wg Maj Gen A K M Abdur Rahman R Adm Muhammad Anwarul Islam Col (Now Brig Gen) F M Zahid Hussain Col (Now Brig Gen) Abu Sayed Mohammad Ali 4 SDS (Army) - 1 SDS (Navy) DS (Army) - 1 DS (Army) - 2 5 AVM M Sanaul Huq Brig Gen Mesbah Ul Alam Chowdhury Capt Syed Misbah Uddin Ahmed Gp Capt Javed Tanveer Khan SDS (Air) SDS (Army) -2 (Now CI, AFWC Wg) DS (Navy) DS (Air) Jt Secy (Now Addl Secy) A F M Nurus Safa Chowdhury DG Saquib Ali Lt Col (Now Col) Md Faizur Rahman SDS (Civil) SDS (FA) DS (Army) - 3 Family Photo: Course Members - NDC 2013 Brig Gen Md Zafar Ullah Khan Brig Gen Md Ahsanul Huq Miah Brig Gen Md Shahidul Islam Brig Gen Md Shamsur Rahman Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Brig Gen Md Abdur Razzaque Brig Gen S M Farhad Brig Gen Md Tanveer Iqbal Brig Gen Md Nurul Momen Khan 6 Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army 7 Brig Gen Ataul Hakim Sarwar Hasan Brig Gen Md Faruque-Ul-Haque Brig Gen Shah Sagirul Islam Brig Gen Shameem Ahmed Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh -

Current Affairs Q&A PDF 2019

Current Affairs Q&A PDF 2019 Current Affairs Q&A PDF 2019 Contents Current Affairs Q&A – January 2019 ..................................................................................................................... 2 INDIAN AFFAIRS ............................................................................................................................................. 2 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS ......................................................................................................................... 94 BANKING & FINANCE ................................................................................................................................ 109 BUSINESS & ECONOMY ............................................................................................................................ 128 AWARDS & RECOGNITIONS..................................................................................................................... 149 APPOINTMENTS & RESIGNS .................................................................................................................... 177 ACQUISITIONS & MERGERS .................................................................................................................... 200 SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY ....................................................................................................................... 202 ENVIRONMENT ........................................................................................................................................... 215 SPORTS -

Directorate of Naval Education Services (DNES) ANNEX a to NHQ Ltr No 06.02.2626.145.40.008

Directorate of Naval Education Services (DNES) ANNEX A TO NHQ Ltr No 06.02.2626.145.40.008. Result Sheet of HET for the Session July 2017 Dated : Total Candidates : 106 Print date : 19/10/2017 Qualified : 6 Print time : 10:35:55AM Absent : 26 Ser O no Full Name Rank Ship/Establishment Currently Failed Subjects Currently Passed Subjects Remarks General Knowledge (P-V) Physics 'A' (P-VII) Previously Passed Subjects Attempt Bangla(P-I) English (P-II) Geography (P-IV) Cycle Mathematics (P-VI) Seaman Branch 1 960272 Md Golam Mostafa PO(CD) BNS SHAPLA 2 4 41.00 I,II,IV,V,VI, Nil VII 2 980078 Md Minhajul Islam PO BNS ISSA KHAN 1 2 43.00 35.00 31.00 28.00 0.00 17.00 Nil Nil I,II,IV,V,VI, VII 3 20000284 Md Momin Uddin PO(GI) BNS ISSA KHAN 2 2 40.00 47.50 0.00 2.00 I,II, Nil IV,V,VI,VII 4 20020285 Md Al Amin LS(GI) BNS BANGABANDHU 1 1 39.00 29.00 11.00 24.50 4.00 0.00 Nil Nil I,II,IV,V,VI, VII 5 20030089 Md Abubakar Siddik LS(GI) BNS SOMUDRA AVIJAN 1 2 50.00 33.00 53.00 I,II,V, IV,VII VI, 6 20030256 Md Razu Ahammed LS BNS TURAG 2 1 44.00 36.00 - 27.50 - - Nil Nil I,II,V, 7 20040064 Md Quamrul Hasan LS BNS ANUSHANDHAN 1 3 50.00 29.00 I,II,V,VI, IV, VII Prepared By M FIROZ BISWAS MD AL-AMIN TALUKDER Checked By Deputy Director Director L/WTR LREN 20070314 20040311 This is a computer generated report. -

UT Also Reports Eight Deaths

K M #('#''$& # '% '($ ''" $*&!$$'( $#(!$$($*!($#+" (#+)' Y $ )($#'')&'')%%$&( '&&+( $&&)%($#&!')"' " C JAMMU, MONDAY, JULY 20 , 2020 VOL. 36 | NO.200 | REGD. NO. : JM/JK 118/15 /17 | E-mail : [email protected] |www.glimpsesoffuture.com | Price : Rs. 2.00 Highest single-day spike of 701 COVID-19 IAF commanders to review air defence system in view of border row with China at 3-day meet cases in J-K; UT also reports eight deaths . %!"-%/ 20B4B0A42C8E4&>B8C8E4 0=38?>A070B?>B8C8E420B4B 20B4BA4?>AC43C>30HF8C7 *>? 2><<0=34AB >5 C74 70E4A42>E4A430=3 8=2;D38=6 20B4BA4?>AC43C> 2C8E4&>B8C8E4 A42>E4A43 =380=8A>A24F8;;20AAH>DC *74>E4A=<4=C>=)D=30H 70E43843 8= 0<<D38E8B8>= 30HF8C7 2C8E4&>B8C8E4 8=2;D38=6 20B4BA42>E4A43C> 0= 8=34?C7 A4E84F >5 C74 8=5>A<43C70C =4F?>B8C8E4 0=3 8=!0B7<8A38E8B8>=*74 A42>E4A438=2;D38=6 20B4BA4 30H0=3 340C7B!D?F0A070B 2>D=CAHB08A3454=24BHBC4<0C 20B4B>5=>E4;>A>=0E8ADB D;;4C8=5DAC74AB083C70C>DC>5 2>E4A43C>30H0=3 340C7B ?>B8C8E420B4B8=2;D38=6 0C7A4430H2>=54A4=241468= %, 5A>< 0<<D C4BCA4BD;CB0E08;01;4 )A8=060A70B ?>B8C8E420B4B 20B4BA4?>AC43C>30HF8C7 =8=6-43=4B30H8=E84F>5C74 38E8B8>=0=3 5A><!0B7<8A B0<?;4B70E4144=C4BC43 8=2;D38=6 20B4BA4?>AC43C> 2C8E4&>B8C8E4A42>E4A43 18CC4A1>A34AA>FF8C778=0 38E8B8>=70E4144=A4?>AC43C> 0B=460C8E4C8;; D;H 30HF8C7 2C8E4&>B8C8E4 8=2;D38=6 20B4BA42>E4A43C> 8=40BC4A="030:70BF4;;0B 30HC7DBC0:8=6C74C>C0;=D<14A 338C8>=0;;HC8;;30C4 A42>E4A438=2;D38=6 30H0=3 340C7BD360<70B 4E>;E8=6A468>=0;B42DA8CHB24 >5?>B8C8E420B4B8= 0<<D0=3 CA0E4;4AB0=3?4AB>=B8= 20B4BA42>E4A43C>30H