Novartis—Gleevec

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verily Forms Strategic Alliances with Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer and Sanofi

Verily Forms Strategic Alliances with Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer and Sanofi to Transform Clinical Research Leading biopharmaceutical organizations join Project Baseline initiative to engage more patients and clinicians in research and speed evidence generation South San Francisco, CA -- May 21, 2019 -- Verily, an Alphabet company, today announced strategic alliances with Novartis (NYSE: NVS), Otsuka (NYSE: OTSKY), Pfizer Inc. (NYSE: PFE) and Sanofi (EURONEXT: SAN, NASDAQ: SNY) to develop digitally innovative, patient-centered clinical research programs using Project Baseline’s evidence generation platform and tools. The Baseline Platform is designed to engage more patients and clinicians in research, increase the speed and ease of conducting studies and collect more comprehensive, higher quality data, including outside the four walls of a clinic. Across the United States, the number of people participating in clinical research -- including clinical trials and observational studies -- is less than 10% of the population.1 In addition to low participation, challenges in research include data fragmentation, inefficient operations and limited value for patients. Alongside academic research institutions, patient-advocacy groups and health systems, Verily and its industry partners aim to implement a more patient-centric, technology-enabled approach to research, and increase the number and diversity of clinical research participants. They will also explore novel approaches to generating real-world evidence using the Baseline Platform to collect, organize and activate health information from electronic health records, sensors and other digital sources. Over the coming years, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer and Sanofi each plan to launch clinical studies leveraging the platform across diverse therapeutic areas, such as cardiovascular disease, oncology, mental health, dermatology and diabetes. -

312.1.Full.Pdf

Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-eular.1066 on 19 May 2021. Downloaded from 312 Scientific Abstracts Acknowledgements: This study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG. The found many DEGs from baseline with GUS treatment and none with PBO. These authors thank Richard Karpowicz, PhD, of Health Interactions, Inc, for providing included genes related to B-, T-, NK-, and plasma cells (increased by GUS) and medical writing support/editorial support, which was funded by Novartis Pharma- neutrophils, monocytes, eosinophils, and macrophages (decreased by GUS), ceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ, in accordance with Good Publication suggestive of a partial normalization of immune cell composition in whole blood. Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3). Conclusion: Using whole transcriptome profiling, we detected DEGs in blood Disclosure of Interests: Gurjit S. Kaeley Consultant of: Novartis Pharmaceuti- samples obtained from PsA pts vs. healthy controls, suggesting a dysregulation cals Corporation, Georg Schett Speakers bureau: AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, of immune cell profiles in PsA. The majority of these disease-associated genes Celgene, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Pfizer, Consultant of: AbbVie, Bristol were modulated by GUS, with directionality toward a normalization of whole Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and UCB, Grant/research blood transcriptomic signatures. support from: Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, GSK, Eli Lilly, and Novartis, Philip REFERENCES: G Conaghan Consultant of: or Speakers bureau: AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bristol [1] Deodhar A et al. Lancet. 2020;395:1115. Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Flexion Therapeutics, Galapagos, Gilead, [2] Mease P et al. Lancet. 2020;395:1126. Novartis, and Pfizer, Grant/research support from: UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Leeds Biomedical Research Centre, Dennis McGona- Table 1. -

CA Signed Novartis 315 Settlement Agreement Signed California

STATE SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT I. PARTIES This Settlement Agreement (the "Agreement") is entered into between the State of California ("the State") and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation ("Novartis"), collectively, "the Parties." II. PREAMBLE As a preamble to this Agreement, the Parties agree to the following: A. At all relevant times, Novartis, (a subsidiary of Novartis International AG, which is headquartered in Basel, Switzerland) was a corporation with its principal place of business in East Hanover, New Jersey, distributed, marketed and/or sold pharmaceutical products in the United States, including drugs sold under the trade names of Lotrel, Valturna, Starlix, Tekamlo, Diovan, Diovan HCT, Tekturna, Tekturna HCT, Exforge, and Exforge HCT (the "Covered Drugs"). B. On January 5, 2011 , Oswald Bilotta, (the "Relater") filed a sealed qui tam action, which was subsequently amended on October 19, 2012, as of right on April 3, 2013 (pursuant to an unopposed motion dated March 21 , 2013), and on July 10, 2013 (pursuant to a stipulation dated July 8, 2013) (the "Civil Action") in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York captioned United States of America et al. , ex rel. Oswald Bilotta et al. v. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation Civil Action No. 1 l-cv-00071 , alleging, inter alia, that Novartis violated the False Claims Act ("FCA") and the Anti-Kickback Statute, 42 U.S.C. §I320a-7b(b) (the "AKS"), by paying doctors remuneration to prescribe the drugs Lotrel, Valturna, Starlix, Tekturna, Tekturna HCT, Diovan, Diovan HCT, Exforge, and Exforge HCT through the mechanism ofspeaker program honoraria and related misconduct. Novartis-315 Page 1 of 19 On April 26, 2013, the United States intervened in the Civil Action against Novartis by filing a Notice of Election to Intervene and Complaint-in-Intervention, in which it is asserted that claims against Novartis under the FCA and common law. -

Event Calendar

Published on Novartis (https://www.novartis.com) Home > Printer-friendly PDF > Event Calendar Event Calendar View recent presentations and learn more about upcoming events. Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The information in the presentations on these pages was factually accurate on the date of publication. These presentations remain on the Novartis website for historical purposes only. Novartis assumes no responsibility to update the information to reflect subsequent developments. Readers should not rely upon the information in these pages as current or accurate after their publication dates. Tab: Upcoming Events Third quarter results 2021 Oct 26, 2021 Basel, Switzerland Recent Events [1] ESG Investor Day Sep 30, 2021 Watch the webcast [2] Download the podcast (MP3 66 MB) [3] Access our interactive slide deck (PDF 9.6 MB) [4] Read the media release [5] Novartis ESG Investor Day 2021 6 key takeaways [6] Bernstein Strategic Decisions Conference Sep 23, 2021 Baader Investment Conference Sep 21, 2021 Bank of America Merrill Lynch Global Healthcare Virtual Conference Sep 15, 2021 Morgan Stanley Global Healthcare Conference Sep 13, 2021 Citi's GEMS Virtual Conference 2021 Sep 8, 2021 Second quarter results 2021 Jul 21, 2021 Basel, Switzerland Media release English (PDF 0.4 MB) [7] Deutsch (PDF 0.4 MB) [8] Français (PDF 0.4 MB) [9] Interim financial report (PDF 0.5 MB) [10] Watch the webcast [11] Read the presentation transcript [12] Download the podcast (MP3 45 MB) [13] Download the interactive presentation (PDF 4.5 MB) [14] Novartis ESG Update - July -

Investor Presentation

Participants Company overview Pharmaceuticals Oncology Financial review Conclusion Appendix References Q1 2021 Results Investor presentation 1 Investor Relations │ Q1 2021 Results Participants Company overview Pharmaceuticals Oncology Financial review Conclusion Appendix References Disclaimer This presentation contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the United States Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, that can generally be identified by words such as “potential,” “expected,” “will,” “planned,” “pipeline,” “outlook,” or similar expressions, or by express or implied discussions regarding potential new products, potential new indications for existing products, potential product launches, or regarding potential future revenues from any such products; or regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on certain therapeutic areas including dermatology, ophthalmology, our breast cancer portfolio, some newly launched brands and the Sandoz retail and anti-infectives business, and on drug development operations; or regarding potential future, pending or announced transactions; regarding potential future sales or earnings of the Group or any of its divisions; or by discussions of strategy, plans, expectations or intentions; or regarding the Group’s liquidity or cash flow positions and its ability to meet its ongoing financial obligations and operational needs; or regarding our collaboration with Molecular Partners to develop, manufacture and commercialize potential medicines for the prevention and treatment of COVID- 19 and our joining of the industry-wide efforts to meet global demand for COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutics by leveraging our manufacturing capacity and capabilities to support the production of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine and to manufacture the mRNA and bulk drug product for the vaccine candidate CVnCoV from CureVac. -

Amc Lapis Glob Top 20 Gen Revol

Data as of 31.08.2021 August 2021 AMC LAPIS GLOB TOP 20 GEN REVOL PRODUCT STRATEGY FACTS AND FIGURES ISIN CH1103333931 The AMC on "LAPIS GLOBAL TOP 20 GENOMIC Currency USD REVOLUTION" is an actively managed portfolio of equities, which is based on investment Maturity Date Open End advice and recommendation by Lapis Asset NAV Date 30.08.2021 Management AG. The Lapis Global Top 20 Genomic Revolution is composed of the worldwide best-known Valor 110333393 and leading top 20 companies (gene therapy, Dividend Reinvested bioinformatics, bio-inspired computing, molecular medicine, pharmaceutical innovation) based on the FX Overlay Disabled research approach of an internationally recognized Issue Date 19.05.2021 company. All stocks are equally weighted and the NAV 110.20 certificate is rebalanced on a quarterly basis (end of January, April, July and October). Mgmt Fee (total) 1.35% Rebalancing Quarterly AuM USD 6’790’721 Components 21 Certificates 61’790 Issuer Bank Julius Baer Last Rebalancing 02.07.2021 PERFORMANCE 1 month -0.81% 52 week high 123.40 3 months 2.04% 52 week low 100.00 1 year N/A All-time high 123.40 Since inception 10.20% All-time low 100.00 YTD N/A Max draw down -14.67% Data as of 31.08.2021 August 2021 PRICE CHART MONTHLY RETURNS 2015 120 2016 115 2017 110 2018 105 2019 2020 100 8.00 13.61 -9.45 -0.81 2021 19 May 8 Jun 29 Jun 19 Jul 9 Aug 30 Aug Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec UNDERWATER EQUITY CURVE PERFORMANCE ANNUAL 0% 10% -5% 8% 2017 - 2018 - 6% 2019 - -10% 2020 - 4% 2021 10.20% 2% -15% 0% 19 May 8 Jun 29 -

French Competition Law Newsletter, October 2020

October 2020 French Competition Law Newsletter — Highlights — The French Competition Authority fines three pharmaceutical companies for abuse of collective dominance — The French Cour de cassation upholds the Paris Court of Appeals’ judgment in the TDF abuse of dominance case — The Cour de cassation quashes the Paris Court of Appeals’ decision in the SFR/Orange case on the fixed telephony market for secondary homes for the second time The French Competition Authority fines three pharmaceutical companies for abuse of collective dominance On September 9, 2020, the French Competition of cancer. Bevacizumab was licensed to its Authority (“FCA”) fined Novartis, Roche and its parent company Roche for distribution outside subsidiary Genentech €444 million for abusing of the United States, and was granted a market their collective dominance on the market for authorization by the European Commission in AMD treatment. The FCA found that the parties 2005. In parallel, having found that Avastin could disparaged the off-label use of Roche’s Avastin also help treat age-related macular degeneration drug and spread an alarmist discourse before (“AMD”), Genentech developed and started the public authorities in order to preserve the selling ranibizumab, a specific molecule (sold dominant position and high price of Novartis’ under the name of Lucentis) that it considered Lucentis drug. more appropriate for treating AMD. Lucentis was licensed to Novartis for distribution outside of Background the United States, and was granted an EU market authorization in 2007. Novartis, already at that In the late 1990ies, US pharmaceutical company time, was one of Roche’s shareholders with a Genentech developed a revolutionary active 33,33% share of the voting rights. -

Executive Summary 1

Executive Summary 1 2 Novartis Pharmaceutical Production campus Executive Summary Cushman & Wakefield, Inc., as exclusive agent, is offering the Novartis Suffern Pharmaceutical Production Campus (the “Property”) for sale. This 585,000 SF multi-building complex is one of the nation’s top ten pharmaceutical manufacturing and packaging plants, with an annual solid dosage capacity in the billions. Owned and operated by Novartis, the Property has served as a vital U.S. production facility for the Company. Due to recent organizational changes and adjustments to the company’s product lines, Novartis will be vacating the facility by year end 2015. The offering provides a buyer with a rare opportunity to purchase an equipped, high-capacity pharmaceutical plant in the New York-New Jersey region. The location and size of the Campus also supports the potential redevelopment of the site for an alternative industrial use. Executive Summary 3 4 Novartis Pharmaceutical Production campus The Campus contains three interconnected buildings including a 55,000 SF office/head building which features a 7,000 SF full-service cafeteria, multiple conference/meeting rooms, and analytical laboratories. The 425,000 SF production/manufacturing building is designed as a multi-product, high volume manufacturing operation with flexible and efficient product flow; the production building contains specialized areas including granulation suites, blending rooms, encapsulation suites, analytical laboratories, inspection areas and packaging lines. The layout of the Complex facilitates the transfer of packaged products to the warehouse/shipping area; the 74,000 SF receiving and warehouse building features 90’ ceiling heights and a fully automated racking system with over 11,500 pallet positions. -

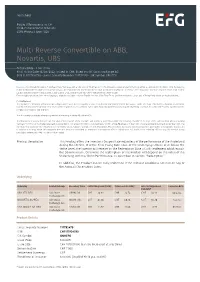

Multi Reverse Convertible on ABB, Novartis, UBS

Termsheet Public Offering only in: CH Yield-Enhancement Products SSPA Product Type: 1220 Multi Reverse Convertible on ABB, Novartis, UBS Autocallable - Low Strike Final Fixing Date 16/09/2022; issued in CHF; listed on SIX Swiss Exchange AG ISIN CH1117924790 - Swiss Security Number 111792479 - SIX Symbol GNHEFG Investors should read the section “Significant Risks” below as well as the section “Risk Factors” of the relevant Issuance and Offering Programme, as amended from time to time. By investing in this product (the "Product"), the Investor may put the capital that he invested in this Product at risk and, in addition, transaction costs may incur. Investors may lose some or all of their capital invested in the Product as well as transaction costs. Investors are exposed to the credit risk of the Issuer. Even though translations into other languages might be available, only the English version of the Final Terms and the relevant Issuance and Offering Programme are legally binding. For Switzerland: This Product is a derivative instrument according to Swiss law. It does not qualify as unit of a collective investment scheme pursuant to article 7 et seqq. of the Swiss Federal Act on Collective Investment Schemes ("CISA") and is therefore neither registered nor supervised by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority FINMA. Investors do not benefit from the specific investor protection provided under the CISA. This document constitutes advertising within the meaning of article 68 of the FinSA. This document is a termsheet prepared in view of the issuance of the Products and neither a prospectus within the meaning of article 35 et seqq. -

Kansas Medical Assistance Program

Kansas Medical Assistance Program Preferred Drug List Committee Meeting Minutes Preferred Drug List Committee Members Present: Representatives: Conrad Duncan (University of Kansas), Meeting Minutes Michael Burke, M.D., Ph.D., Chair Bruce Steinberg (Sanofi-Aventis), Debra Vickers (Sanofi- Capitol Plaza Hotel Kristen Fink, PharmD Aventis), Tom Rickman (Sanofi-Aventis), Bill Giltner Pioneer Room, Robert Haneke, PharmD (Pfizer), Kirk Becker (Pfizer), Colette Wunderlick Maner Conference Center Kenneth Mishler, PharmD (AstraZeneca), Michael Windheuser (GlaxoSmithKline), October 07, 2004 Brenda Schewe, M.D. James Lieurance (TPNA), Kim Kraenow (TPNA), Danny 10:00 A.M.-4:00 P.M. Dennis Tietze, M.D. Ottosen (Bertek Pharmaceuticals), Neal Beasly (Bristol Myers Squibb), Marguerite Enlow (Bristol Myers Squibb), SRS Staff Present: Dennis Jacobson (Sanofi-Aventis), Chris Lepore (Johnson Nialson Lee, B.S.N, M.H.A. & Johnson),Cheryl Edwards (Reliant Pharmaceuticals), Mary Obley, R.Ph. Candie Phipps (Boehringer Ingelheim), Patrick Byler Vicki Schmidt, R.Ph. (Novartis), Randy Blackwell (Biovail Pharmaceuticals), Erica Miller Mike Moratz (Merck), Dennis Bresnahan (University of Kansas Hospital – Cardiologist), James Simple (AstraZeneca),Robert Greely (Takeda), John Kiefhaber (Kansas Pharmacist Association), Joshua Lang (Novartis), Kathleen Carmody (Eli Lilly), Hal Pierce (HealthPoint), James Rider, D.O. (Geriatrics), Carol Curtis (AstraZeneca), Randy Beckner (GlaxoSmithKline), John Hawley (Reliant Pharmaceuticals), Lon Lowrey (Novartis), Scott Wilson (Andrx), Gil Preston (Watson), Matt Ackermann (Boehringer Ingelheim), Brian Michael (Novartis), Mark Ritter (Proctor & Gamble), Jason Heiderscheidt (Proctor & Gamble), Mark Hershy (Aventis), Jeffrey Fajando (Topeka Infectious Disease), Holli Hill (Sankyo Pharma), Craig Wildey (Sankyo Pharma), Barbara Boner (Novartis), Jacqueline Houston (Coventry Health Care), Elias Tawil, M.D., F.A.C.S. (Physician), Karil Bellah (Sankyo Pharma), Amy Siple, MSN, ARNP (Bio-Vail), Michael Martin (Bio-Vail) I. -

F. Hoffmann-La Roche and Novartis

PRIVILEGED AND CONFIDENTIAL ATTORNEY – CLIENT COMMUNICATION C a s e C - 1 7 9 / 1 6 F. Hoffmann - La Roche and Novartis – ECJ finds concerted efforts to restrict off - label use of medicinal products likely to breach competition rules 1. INTRODUCTION On 23 January 2018 the Court of Justice of the European Union (the ECJ) handed down its judgment in Case C-179/16 F. Hoffmann-La Roche and Novartis. The case concerned the Italian subsidiaries of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd (Roche) and Novartis AG (Novartis). Largely following the Opinion of Advocate General Saugmandsgaard Øe (the AG), the ECJ held (i) that the content of a marketing authorisation does not determine the scope of the relevant product market so long as other conditions are fulfilled; (ii) that a licensing agreement between non-competitors may fall within EU competition rules; and (iii) that the coordinated dissemination of misleading safety claims may constitute a serious violation of competition rules. 2. FACTS Through its US subsidiary Genentech, Roche developed two medicines from related active substances. The first, Avastin® (bevacizumab), was granted a marketing authorisation (MA) for an oncological indication. The second, Lucentis® (ranibizumab), was developed later and was granted an MA specifically for the treatment of ophthalmological conditions such as macular degeneration and glaucoma. A practice developed whereby doctors prescribed Avastin® for the treatment of eye conditions. The Italian health authority permitted, and later encouraged, this ‘off-label’ use, even after Lucentis® had received its own MA and obtained reimbursement for that indication. Novartis licensed Lucentis® from Genentech, and moreover owns a 33% share in Roche itself. -

Proposed Spin-Off of Alcon

PROPOSED SPIN-OFF OF ALCON | A Proposed Spin-off of Alcon Shareholder Information Brochure General Meeting of Shareholders of Novartis AG February 28, 2019 Brochure dated as of January 30, 2019 B | PROPOSED SPIN-OFF OF ALCON Important Information This information brochure has been prepared exclusively for the We urge future holders of Alcon Shares to read the Form 20-F on shareholders of Novartis AG and holders of Novartis American file with the SEC or the SIX listing prospectus, once available, and Depositary Receipts (“ADRs”) in connection with the spin-off of Alcon familiarize themselves with the entire content, including the risk factors. proposed to the annual general meeting of Novartis shareholders to be held on February 28, 2019 (the “General Meeting”). The information set out herein and in any related materials is subject to updating, completion, revision, verification and/or amendment. This brochure is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of offers to Neither Novartis AG nor Alcon Inc. nor any of their affiliates or their purchase or subscribe for shares in Novartis AG or Alcon Inc. nor respective bodies, executives, employees and advisers are under any shall it or any part of it nor the fact of its distribution form the basis obligation to update or keep current the information contained in this of, or be relied on in connection with, any contract therefor. This brochure or to correct any inaccuracies except to the extent it would brochure does not constitute a listing prospectus as defined in the be required under applicable law or regulation.