The Indus Delta Country; a Memoir Chiefly on Its Ancient Geography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

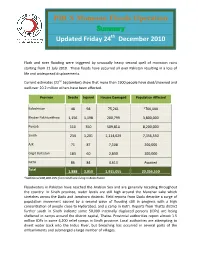

PRCS Monsoon Floods Operation Summary Updated Friday 24Th December 2010

PRCS Monsoon Floods Operation Summary th Updated Friday 24 December 2010 Flash and river flooding were triggered by unusually heavy second spell of monsoon rains starting from 21 July 2010. These floods have occurred all over Pakistan resulting in a loss of life and widespread displacements. Current estimates (22nd September) show that more than 1900 people have died/drowned and well over 20.2 million others have been affected. Province Deaths Injured Houses Damaged Population Affected Balochistan 48 98 75,261 *700,000 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 1,156 1,198 200,799 3,800,000 Punjab 110 350 509,814 8,200,000 Sindh 234 1,201 1,114,629 7,356,550 AJK 71 87 7,108 200,000 Gilgit Baltistan 183 60 2,830 100,000 FATA 86 84 4,614 Awaited Total 1,888 3,050 1,915,055 20,356,550 *Additional 600,000 IDPs from Sindh are living in Balochistan Floodwaters in Pakistan have reached the Arabian Sea and are generally receding throughout the country. In Sindh province, water levels are still high around the Manchar Lake which stretches across the Dadu and Jamshoro districts. Field reports from Dadu describe a surge of population movement caused by a second wave of flooding still in progress with a high concentration of people close to Hyderabad, and a camp in Kotri. Reports from Thatta district further south in Sindh indicate some 50,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) are being sheltered in camps around the district capital, Thatta. Provincial authorities report almost 1.5 million IDPs in some 4,200 relief camps in Sindh province. -

The Land of Five Rivers and Sindh by David Ross

THE LAND OFOFOF THE FIVE RIVERS AND SINDH. BY DAVID ROSS, C.I.E., F.R.G.S. London 1883 Reproduced by: Sani Hussain Panhwar The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 TO HIS EXCELLENCY THE MOST HONORABLE GEORGE FREDERICK SAMUEL MARQUIS OF RIPON, K.G., P.C., G.M.S.I., G.M.I.E., VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, THESE SKETCHES OF THE PUNJAB AND SINDH ARE With His Excellency’s Most Gracious Permission DEDICATED. The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 PREFACE. My object in publishing these “Sketches” is to furnish travelers passing through Sindh and the Punjab with a short historical and descriptive account of the country and places of interest between Karachi, Multan, Lahore, Peshawar, and Delhi. I mainly confine my remarks to the more prominent cities and towns adjoining the railway system. Objects of antiquarian interest and the principal arts and manufactures in the different localities are briefly noticed. I have alluded to the independent adjoining States, and I have added outlines of the routes to Kashmir, the various hill sanitaria, and of the marches which may be made in the interior of the Western Himalayas. In order to give a distinct and definite idea as to the situation of the different localities mentioned, their position with reference to the various railway stations is given as far as possible. The names of the railway stations and principal places described head each article or paragraph, and in the margin are shown the minor places or objects of interest in the vicinity. -

Budget Speech by Murad Ali Shah Minister for Finance on 7Th June 2012

BUDGET SPEECH BY MURAD ALI SHAH MINISTER FOR FINANCE ON 7TH JUNE 2012 Budget Speech 2012-13 Honorable Mr. Speaker, I am grateful to Almighty Allah for the honour that he has bestowed upon me. Sir, I feel privileged to stand before this august house to present the fifth budget of this democratically elected government in Sindh. It is with pleasure that I present this budget free of anynew taxes. It is indeed a tribute to our great leaders Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Shaheed Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto that the PPP-led coalition government in Sindh has been able to bring perceptible improvement in the lives of our people. The visionary ideals laid down by Quaid-e-Azam inspired our leaders and guided each and every member of our government to reach this milestone. Mr. Speaker, over the last four years, the PPP-led government at the Centre and here in Sindh, has faced a multitude of challenges. Many of these were legacies of mismanagement passed down from previous regimes. Natural calamities the likes of which have not been seen at least in the recorded history also hampered our development. Despite these obstacles, under the brave and pragmatic leadership of the Honourable President of Pakistan Mr. Asif Ali Zardari and the Honourable Prime Minister of Pakistan Syed Yusuf Raza Gillani and the guidance of Chief Minister Sindh Syed Qaim Ali Shah, we have successfully moved ahead and overcome the challenges with unflinching democratic will and commitment. We have remained steadfast in our resolve to strengthen democratic institutions in the country and have pursued the agenda based on reconciliation and consensus building with the broader objective of serving the people of Sindh to the best of our abilities. -

Press Clippings from the Pakistan Disaster

Associated Press Of Pakistan ( Pakistan's Premier NEWS Agency ) - President orders ... Side 1 af 1 President orders probe into reports of discrimination against minorities in relief operations SUKKUR, Sep 1 (APP) President Asif Ali Zardari has taken exception to the media reports that some members of the minority communities were denied flood relief assistance and driven out of the relief camps in Sindh province and called for an inquiry and action against officials if found involved. Spokesperson to the President, Farhatullah Babar said that the President taking note of media reports of a protest rally in Hyderabad on Monday against the maltreatment of Dalits in flood relief called for a probe into the matter and steps to ensure that no discrimination was shown in the relief and rehabilitation operations. The President said that floods were a natural disaster and should serve to unite the people, not divide them. It will be most unfortunate and reflect poorly on the country’s image and adversely impact on national unity if relief work was influenced by considerations of caste, creed or ethnicity. “All citizens of the country have equal rights and more so people who have been hit by the worst natural disaster in the history of the country. Discrimination on ethnic or religious grounds cannot be tolerated”, he added. President Zardari called for an inquiry into the reports of discrimination and appropriate measures to ensure that the relief work was not influenced by such considerations. The President also called for action against officials if found involved in discrimination in the relief and rehabilitation works, the spokesperson said. -

Pakistan: GLIDE N° FL-2010-000141-PAK Operations Update N° 12 Monsoon Flash 23 December 2010 Floods

Emergency appeal n°MDRPK006 Pakistan: GLIDE n° FL-2010-000141-PAK Operations update n° 12 Monsoon Flash 23 December 2010 Floods Period covered by this operations update: 11 November - 10 December 2010. Appeal target (current): CHF 130,673,677 (USD 133.8 mil or EUR 97.9 mil); Appeal coverage: To date, the appeal is 60.4 per cent covered in cash and kind; and 66.8 per cent covered including contributions currently in the pipeline. Funds are still urgently needed to support the Pakistan Red Crescent Society in this operation to assist those affected by the floods. <see updated donor response report; or contact details> Appeal history: • A revised emergency appeal was launched on 15 November 2010 for CHF 130,673,677 (USD 133.8 mil or EUR 97.9 mil) to assist 130,000 families (some 900,000 people) for 24 months. • The revised emergency appeal was launched on 19 August 2010 for CHF 75,852,261 (USD 72.5 mil or EUR 56.3 mil) for 18 months to assist 130,000 flood-affected families (some 900,000 beneficiaries). • An emergency appeal was initially launched on a preliminary basis on 2 August 2010 for CHF 17,008,050 (USD 16,333,000 or EUR 12,514,600) for 9 months to assist 175,000 beneficiaries. • Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF): CHF 250,000 Fatigued from months of living on humanitarian (USD 239,406 or EUR 183,589) was allocated on 30 July assistance, flood-affected families are eager to 2010 to support the National Society’s response to the resume normal lives. -

4 Chronology of Disaster in Pakistan 2012 (25Th August-15Th October)

Strengthening Participatory Organization (SPO) SPO is one of the largest rights-based civil society organization in Pakistan. It is pursuing various program components presently being implemented in over 75 districts of the country. SPO seeks to address mainly governance, social and political issues in the country through its programmes focussing on democratic th governance, social justice, peace and harmony, institutional strengthening, conflict resolution, citizens engagement, gender, electoral reforms and political parties development. Parallel to these activities, SPO deals with humanitarian 15August - October) emergencies resulting from both natural and human-induced hazards. In th emergencies, it has been dealing to redress problems of disaster like (25 earthquakes, rain-fed floods, cyclones and rehabilitation of internally displaced communities affected by conflicts. Chronology of Disaster in Pakistan 2012 Protection and promotion of human rights is central to the program philosophy of SPO. Its various citizens voices and accountability initiatives seek to strengthen democratic processes through engagement with and building capacities of civil society and state institutions and harness mutual tolerance, peace and harmony between various political, ethnic and religious groups across rural and urban parts of the country. Various components of SPO's citizens voices and accountability initiatives are currently supported by Australian Agency for International Development (AusAid), British High Commission (BHC), Embassy for the Kingdom of Netherlands (EKN), DFID and USAID. SPO also acknowledges support from other donors for its various program components SPO National Center 30-A, Nazimuddin Road, F-10/4, Islamabad, Pakistan UAN: +92-51-111-357-111 Tel: +92-51-2104677, 2104679 Fax: +92-51-2112787 [email protected] www.spopk.org BALOCHISTAN KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PUNJAB SINDH AZAD JAMMU KASHMIR QUETTA PESHAWAR MULTAN HYDERABAD MUZAFFARABAD House 58-A, Near Pak Japan House 15, Street 1, Sector N-4 House 339-340, Block-D Plot 158/2, Behind M. -

Weekly Epidemiological Bulletin Disease Early Warning System and Response in Pakistan

Weekly Bulletin Epidemiological Disease early warning system and response in Pakistan Volume 2, Issue 46, Monday 21 November, 2011 Highlights Priority diseases under surveillance Epidemiological week no. 46 (11 to 17 November, 2011) in DEWS • 80 districts and 2 agencies provided surveillance data to the DEWS this week from Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) 2,636 health facilities. Data from mobile teams is reported through sponsoring BHU or Acute Jaundice Syndrome (AJS) RHC. Acute Respiratory Infections • A total of 816,850 consultations were reported through DEWS of which 203,121 (Upper and Lower) (ARI) (25%) were acute respiratory infections (ARI); 72,768 (9%) were Skin disease; 61,792 Acute Watery Diarrhoea (AWD)/ (8%) were acute diarrhoea; and 57,597 (7%) were suspected malaria. Suspected Cholera • A total of 124 alerts with 10 outbreaks were reported in week‐46, 2011: Altogether Acute Bloody Diarrhoea (BD) 28 alerts for AWD, 23 for Measles; 22 for Neonatal tetanus and tetanus; 18 for Other Acute Diarrhoeas (AD) Leishmaniasis; 7 for Pertussis; 6 each for Malaria and ARI; 4 each for DHF and Acute diarrhoea; 2 for AJS; while 1 each for CCHF, Diphtheria, Typhoid and unexplained fever. Suspected Viral Hemorrhagic Fever (VHF) • In this week nine new polio cases were confirmed by the laboratory, four from Suspected Malaria (Mal) FATA (three from North Waziristan agency and one from Khyber agency); two each Suspected Measles (MS) from Balochistan (Mastung and Barkhan districts) and Punjab (Vehari and Rahim Yar Khan districts); and one from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Lakki Marwat district). As of 21st Suspected Meningitis (MG) November 2011, Pakistan has reported a total of 154 polio cases (152 type‐1 & 2 type‐ Others 3) from 48 districts/towns/tribal agencies and areas. -

Jhirk Mulla Katiyar Bridge Project

Jhirk Mulla Katiyar Bridge Project Volume 1 :Request for Proposal (RFP) Jhirk Mulla Katiyar Bridge Project Works and Services Department Public Private Partnership Unit Government of Sindh Finance Department Government of Sindh 1 December 2011 Jhirk Mulla Katiyar Bridge Project Reference: Jhirk Mulla Katiar Bridge Project Dear Bidder, The Works and Services Department Government of Sindh ("GoS"), in association with the Public Private Partnership (“PPP”) Unit of the Finance Department, GoS hereby invites proposals from Bidders. This RFP represents the process of selecting a Private Partner with whom the GoS intends to sign a Concession Agreement for the Design, Build, Finance, Operate and Transfer a 25 km road and Bridge of 1.2 km connecting National Highway (N5) via Jhirk to Tando Muhammad Khan Bathoro Road (the “Project”). It is currently envisaged that the contract term will be for a period of approximately 27 years. The Project (including the ownership of the Project related assets) shall be handed over to GoS at the end of the contract period. In order for a Proposal to be evaluated, Bidders must meet all of the eligibility requirements stated herein. The key dates in this stage of the selection process are as follows: Pre-bid Conference 30th Dec 2011 Submission of Proposal 31st Jan 2012 Concession Agreement signing 28th Feb 2012 Financial Close 30th Jun 2012 Concession period Anticipated start of design 01st Mar 2012 Anticipated end of design 30th May 2012 Anticipated start of construction 01st June 2012 Anticipated end of construction 30th Jun 2014 Anticipated expiry of Concession Agreement & handover of 30th June 2039 facilities 2 Jhirk Mulla Katiyar Bridge Project Two (2) complete hard copies and one (1) complete soft copy of the technical and financial proposal (including the Financial model in Excel spreadsheet) and other supporting documents form (on CD/ DVDs) must be delivered no later than 4:00 p.m. -

Budget Speech by Syed Qaim Ali Shah Jillani Chief Minister Sindh on 11Th June 2010

BUDGET SPEECH BY SYED QAIM ALI SHAH JILLANI CHIEF MINISTER SINDH ON 11TH JUNE 2010 Budget Speech 2010-2011 Bismillah- e- Rehman-er-Raheem Mr. Speaker It is indeed an honor for me to present the 3rd Budget of the Pakistan Peoples’ Party led coalition Government in Sindh. I am thankful to Almightly Allah for his blessings and for this opportunity to serve the people of Sindh. Earlier in mid- April, I placed the Government’s Performance Report before this August House for informing the people about the major programs and activities which have been started to provide relief to the people; to trigger growth in different sectors and to strengthen the human development efforts. The Pakistan Peoples’ Party led Government at the centre and here in Sindh has faced one challenge after another in the last two years but we have remained steadfast in our resolve to strengthen the democratic institutions in the country. Today, the parliament, the judiciary, as well as the media are fully independent and the levels of check and balance of one institution over the other, have increased and strengthened to a great extent. The policy of reconciliation initiated by Shaheed Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto effectively followed by our Co-Chairman and the President of Pakistan has paid off huge dividends. At our level it has helped to create greater understanding with MQM under the leadership of Mr. Altaf Hussain, PML (Functional) under the leadership of Pir Sahib Pagaro, ANP under the leadership of Mr. Asfand Yar Wali Khan, NPP under the leadership of Ghulam Murtaza Khan Jatoi and PML(Q). -

Technical Assessment Survey Report of WSS Sindh Province Ii

Technical Assessment Survey Report of WSS District Hyderabad Technical Assessment Survey Report of WSS Sindh Province TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS.......................................................................................................... ii LIST OF TABLES................................................................................................................... iv STATEMENT BY THE FEDERAL SECRETARY, MINISTRY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY ........................................................................................................................v PREFACE................................................................................................................................ vi LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS................................................................................................. vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..................................................................................................... viii STAFF ASSOCIATED WITH TECHNICAL ASSESSMENT SURVEY............................. ix EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................x CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................1 1.1 Background....................................................................................................................1 1.2 Provision of Safe Drinking Water Project .....................................................................2 1.3 Technical Assessment -

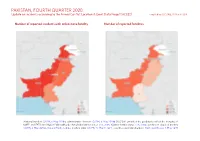

PAKISTAN, FOURTH QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

PAKISTAN, FOURTH QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b (ACCORD amended the geodata to reflect the merging of NWFP and FATA into Khyber Pakhtunkhwa); China/India border status: CIA, 2006; Kashmir border status: CIA, 2004; geodata of disputed borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; Natural Earth, nodate; incident data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 PAKISTAN, FOURTH QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Protests 2139 0 0 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 87 46 158 Development of conflict incidents from December 2018 to December 2020 2 Riots 50 5 11 Explosions / Remote Methodology 3 35 20 75 violence Conflict incidents per province 4 Violence against civilians 29 22 27 Strategic developments 8 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 2348 93 271 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from December 2018 to December 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). -

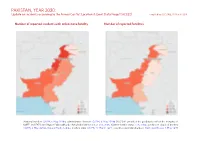

PAKISTAN, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

PAKISTAN, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b (ACCORD amended the geodata to reflect the merging of NWFP and FATA into Khyber Pakhtunkhwa); China/India border status: CIA, 2006; Kashmir border status: CIA, 2004; geodata of disputed borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; Natural Earth, nodate; incident data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 PAKISTAN, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Protests 8109 1 11 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 270 173 519 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2020 2 Riots 191 20 39 Violence against civilians 113 75 95 Methodology 3 Explosions / Remote 100 50 150 Conflict incidents per province 4 violence Strategic developments 29 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 8812 319 814 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 PAKISTAN, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology Geographic map data is primarily based on GADM, complemented with other sources if necessary.