Witgenstein-And-Kiekegard-Relgion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking Fideism Through the Lens of Wittgenstein's Engineering Outlook

University of Dayton eCommons Religious Studies Faculty Publications Department of Religious Studies 2012 Rethinking Fideism through the Lens of Wittgenstein’s Engineering Outlook Brad Kallenberg University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/rel_fac_pub Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons eCommons Citation Kallenberg, Brad, "Rethinking Fideism through the Lens of Wittgenstein’s Engineering Outlook" (2012). Religious Studies Faculty Publications. 82. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/rel_fac_pub/82 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Note: This is the accepted manuscript for the following article: Kallenberg, Brad J. “Rethinking Fideism through the Lens of Wittgenstein’s Engineering Outlook.” International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 71, no. 1 (2012): 55-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11153-011-9327-0 Rethinking Fideism through the Lens of Wittgenstein’s Engineering Outlook Brad J. Kallenberg University of Dayton, 2011 In an otherwise superbly edited compilation of student notes from Wittgenstein’s 1939 Lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics, Cora Diamond makes an false step that reveals to us our own tendencies to misread Wittgenstein. The student notes she collated attributed the following remark to a student named Watson: “The point is that these [data] tables do not by themselves determine that one builds the bridge in this way: only the tables together with certain scientific theory determine that.”1 But Diamond thinks this a mistake, presuming instead to change the manuscript and put these words into the mouth of Wittgenstein. -

A REDUCTIVE READING of the TRACTATUS Interpretation of the Book Being About How to Defeat Skepticism

2015 Umeå University, Department of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies Stefan Karlsson Supervisor: Andreas Stokke Examinor: Peter Melander Level: Bachelor’s thesis A REDUCTIVE READING OF THE TRACTATUS Interpretation of the book being about how to defeat skepticism. Content Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Traditional readings ................................................................................................................................. 7 Meta-physical interpretations ............................................................................................................. 7 Traditional readings of the nonsense concept in the Tractatus ......................................................... 8 The ineffable truth interpretation ................................................................................................... 8 What can be said and what can be shown ...................................................................................... 9 Modern readings .................................................................................................................................. -

Wittgenstein in Exile

Wittgenstein in Exile “My thoughts are one hundred per cent Hebraic.” -Wittgenstein to Drury, 19491 Wittgenstein was born in 1889 into one of the richest families in Central Europe. He lived and learned at home, in Vienna, until 1903, when he was 14. We have no record of his thoughts about the turn of the last century, but it is unlikely that it seemed very significant to him. The Viennese of the time had little inclination to consider the possibilities of change, and the over-ripe era in which Wittgenstein grew up did not really end until Austria-Hungary’s defeat, in World War I, and subsequent dismantling. But the family in which Wittgenstein grew up apparently felt that European culture had already come to an end in the 1840’s. And Wittgenstein himself felt he belonged to an era that had vanished with the death of the composer Robert Schumann (1810-1856).2 Somewhere in the middle of the Nineteenth Century there was an important change into the contemporary era, of which Wittgenstein did not feel a part. Wittgenstein’s understanding of history, and his consequent self-understanding in relation to his times, was deeply influenced by Oswald Spengler, who in 1918 published The Decline of the West [Der Untergang des Abenlandes]. This book, expanded to a second volume in 1922, and revised in 1923, became a best-seller in post-war Europe. Wittgenstein made numerous references to it in 1930-1931, and acknowledged Spengler as one of his ten noteworthy influences.3 According to Spengler, cultures grow, flower, and deteriorate naturally, according to their own internal form, much as a human being does. -

Wittgenstein on the Nature of British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Philosophy J Wittgenstein and His Times

@Basil Blackwdl Publisher Limitcd 1982 Contents Fiesr published 1982 Basil BlackwelJ Publisher Limited 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 IJF, England All rights rcserved. No part ofthis publicarion may bc reproduccd, stored in a retricval system, or trammitted. in an y form or hy any means. clcctronic, mcchanicaJ, photocopying. recording or otherwisc. withollt the prior permission of Basil Blackwell Publisher Limited. Editor's Preface v Anthony Kenny Wittgenstein on the Nature of British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Philosophy J Wittgenstein and his times. Brian McGuinness Freud and Wittgenstein 27 I. Wittgenstein, Ludwig I. McGuinness, Brian J. C. NYlri Wittgenstein's Later Work in '92 B)376.W)64 reiation co Conservatism 44 ISBN 0-63'-11161-1 Rush Rhees Wittgenstein on Language and Ritual 69 G. H von Wright Wittgenstein in relation to his Times 108 Index 121 Printe<! in Great Britain at Thc Blackwell Press Limitcd, Guildford, Landon, Oxford, Worcester. LATER WORK IN RELATION 1'0 CONSERVATISM 45 since Wittgenstein 's position in respect to the body ofconserva Wittgenstein 's Later Work in relation tive literature cannot be satisfactorily dctcrmined in the absence to Conservatism * ofa thorough analysis ofhis unpublished manuscripts. I Still, the interpretation here presented, cven ifmerely an approximation, C. Nyiri seems to me to constitute a necessary step towards a more J. complere pieture of Wittgenstcin's philosophy. Wittgenstein's later philosophy emerged at a time when conservatism - in tbe form of neo-conservatism - was one of the dominant spiritual currents in Germany and Austria; and Wittgenstein received decisive impulses both from authors who deeply influenced this The well-kno"vn fact that in Wittgenstein's later philosophy current and trom representatives ofthe I1ew conservatism itself. -

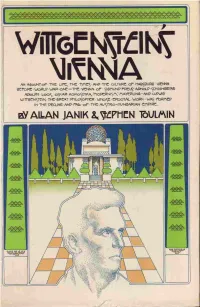

Wittgenstein's Vienna Our Aim Is, by Academic Standards, a Radical One : to Use Each of Our Four Topics As a Mirror in Which to Reflect and to Study All the Others

TOUCHSTONE Gustav Klimt, from Ver Sacrum Wittgenstein' s VIENNA Allan Janik and Stephen Toulmin TOUCHSTONE A Touchstone Book Published by Simon and Schuster Copyright ® 1973 by Allan Janik and Stephen Toulmin All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form A Touchstone Book Published by Simon and Schuster A Division of Gulf & Western Corporation Simon & Schuster Building Rockefeller Center 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10020 TOUCHSTONE and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster ISBN o-671-2136()-1 ISBN o-671-21725-9Pbk. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 72-83932 Designed by Eve Metz Manufactured in the United States of America 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 The publishers wish to thank the following for permission to repro duce photographs: Bettmann Archives, Art Forum, du magazine, and the National Library of Austria. For permission to reproduce a portion of Arnold SchOnberg's Verklarte Nacht, our thanks to As sociated Music Publishers, Inc., New York, N.Y., copyright by Bel mont Music, Los Angeles, California. Contents PREFACE 9 1. Introduction: PROBLEMS AND METHODS 13 2. Habsburg Vienna: CITY OF PARADOXES 33 The Ambiguity of Viennese Life The Habsburg Hausmacht: Francis I The Cilli Affair Francis Joseph The Character of the Viennese Bourgeoisie The Home and Family Life-The Role of the Press The Position of Women-The Failure of Liberalism The Conditions of Working-Class Life : The Housing Problem Viktor Adler and Austrian Social Democracy Karl Lueger and the Christian Social Party Georg von Schonerer and the German Nationalist Party Theodor Herzl and Zionism The Redl Affair Arthur Schnitzler's Literary Diagnosis of the Viennese Malaise Suicide inVienna 3. -

Introduction 1 Problems of Interpretive Authority in Wittgenstein's Corpus

Notes Introduction 1 . See chapter 8, ‘Contested Concepts, Family Resemblances and Tradition’ in Glock, 2008. 2 . This has been a central topic of dispute within religious studies and cognate academic fields. See Asad, 1993; Taylor, 1998; and Smith, 2004. 3 . A recent example of this kind of approach is found in DuBois, 2011. DuBois’s book is a good example of the way a perspicuous overview through concep- tual genealogy can dispel numerous sources of confusion (for example, the debate over whether it is appropriate to classify a tradition like Confucianism as a religion or not). 1 Problems of Interpretive Authority in Wittgenstein’s Corpus 1 . According to one bibliography, over 600 books, articles, or theses have been written on topics relevant to Wittgenstein and religion between the 1950s and the year 2000 (Stagaman, Kraft and Sutton, 2001). 2 . The editors of that now classic collection in analytic philosophy of religion, New Essays in Philosophical Theology , Alasdair MacIntyre and Anthony Flew, chose the name ‘philosophical theology’ over ‘philosophy of religion’ for their collection due to the latter’s association with ‘Idealist attempts to present philosophical prolegomena to theistic theology’ (MacIntyre and Flew, 1955, p. viii). 3 . Norman Malcolm writes of an encounter with Wittgenstein: ‘One time when we were walking along the river we saw a news vendor’s sign which announced that the German government accused the British government of instigating a recent attempt to assassinate Hitler with a bomb. This was the autumn of 1939. Wittgenstein said of the German claim: “It would not surprise me at all if it were true.” I retorted that I could not believe that the top people in the British government would do such a thing. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Not Beyond Language: Wittgenstein and Lindbeck on the Problem of Speaking about God Khay Tham Nehemiah Lim Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2019 Declaration I, Khay Tham Nehemiah Lim, declare that this thesis has been composed solely by myself and that it has not been submitted, in whole or in part, in any previous application for a degree. Except where stated otherwise by reference or acknowledgment, the work presented is entirely my own. Signature: ________________________ Date: ___________________ iii To Jenise whose faith in me has been unswerving and whose encouragement has helped me stay the course. My debt of gratitude to her is beyond language. iv Abstract The problem of speaking about God arises from the claim that God is utterly transcendent and is ‘wholly other’ from human or this-worldly existence. -

Ilse-Somavilla.Pdf

Ilse Somavilla Curriculum Vitae Born in Fulpmes, Austria. Studies of philosophy, psychology and English at the University of Innsbruck. 1988 Mag. phil., 1997 Dr. phil. Since 1990 researcher on Ludwig Wittgenstein at the Brenner-archives, University of Innsbruck. In1993 and in 1996 research work at the Wittgenstein archives at the University of Bergen, Norway. In 1998 research on Paul Engelmann in Jerusalem. Seminars about ethics and aesthetics (in the philosophies of Spinoza, Schopenhauer and Wittgenstein) at the Universities of Innsbruck and of Klagenfurt. About 45 speeches at international conferences in Spain, Greece, Portugal, Germany, France, Poland, Austria and in the USA. Main topics: Ethics, aesthetics and religion. Wittgenstein, Schopenhauer, Spinoza, Kierkegaard and Ancient Greek philosophy. Editions: Ludwig Hänsel – Ludwig Wittgenstein. Eine Freundschaft. Briefe. Aufsätze. Kommentare. (in collaboration with Anton Unterkircher und Christian Paul Berger). Innsbruck: Haymon, 1994. Denkbewegungen. Tagebücher 1930-1932/1936-1937. Innsbruck: Haymon, 1997. (Since 1999 also as paperbook published by Fischer). Translations into Norwegian (Spartacus Forlog, 1998), into Italian (Quodlibet, 1999), into French (Presses Universitaires de France, 1999), into Dutch (Boom, 1999), into Spanish (Pre-Textos, 2000), into Polish, into Russian, into English (Rowman & Littelfield, 2003), into Japanese (2005), into Portuguese (Martins Fontes, 2010) and into Finnish (Tampere, 2011). Ludwig Wittgenstein. Licht und Schatten. Ein nächtliches (Traum-)Erlebnis und ein Brief- Fragment. Innsbruck: Haymon, 2004. Translations into Spanish (Pre-Textos, 2006), into Italian, into Dutch (Ten Have, 2007), into French (Agone, 2011) and into Portuguese (Martins Fontes, 2012). 1 Wittgenstein – Engelmann. Briefe, Begegnungen, Erinnerungen. (in collaboration with Brian McGuinness) Innsbruck: Haymon, 2006. Translations into Spanish (Pre.-Textos, 2009) and into French (Éditions de l’éclat, 2010). -

One Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: Necessity and Normativity Gregory P

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Philosophy Honors Projects Philosophy Department June 2007 One Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: Necessity and Normativity Gregory P. Taylor Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/phil_honors Recommended Citation Taylor, Gregory P., "One Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: Necessity and Normativity" (2007). Philosophy Honors Projects. Paper 1. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/phil_honors/1 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. One Tractatus Logico-philosophicus: Necessity and Normativity Greg Taylor Honors Thesis Macalester College 2007 Committee: Janet Folina (advisor), Joy Laine, Jeffrey Johnson This thesis is dedicated to Janet Folina, a friend who – more than anyone else – has helped me think. I would also like to thank the Macalester Philosophy faculty and the members of Mac Thought for their frequent stimulation and support. Abstract This thesis sketches an interpretation of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus centering on his treatment of necessity and normativity. The purpose is to unite Wittgenstein’s account of logic and language with his brief remarks on ethics by stressing the transcendental nature of each. Wittgenstein believes that both logic and ethics give necessary preconditions for the existence of language and the world, and because these conditions are necessary, neither logic nor ethics can be normative. I conclude by erasing the standard line drawn between his philosophy and his ethics, and redrawing it between the philosophical and artistic presentations of his thought, the latter being what remains after the nonsensical status of the work is recognized. -

Wittgenstein's Architectural Idiosyncrasy

Wittgenstein’s architectural idiosyncraSy august sarnitz Ludwig Wittgenstein was deeply embedded in Viennese architectural Modernism, culturally as well as personally. His assimilation in recent historiography to existing trends within the local architectural movement—namely Loos—are based on aesthetic and intellectual simplifications. The simplifications eclipse the distinctive contribution Wittgenstein’s Palais Stonborough makes to architecture, to Viennese Modernism, and perhaps to philosophy. The present paper seeks to rectify this constellation by re-situating Wittgenstein as an architect in his own right by re-sensitizing us to the idiosyncrasy of Wittgenstein’s architecture [1]. The paper begins by looking at the wider biographical background setting the foundation Wittgenstein’s involvement with architecture in Vienna. It scrutinizes his own as well as the family’s wider personal connections to key figures in Viennese Modernism, with special focus on Josef Hoffmann and Adolf Loos. As will be shown, Wittgenstein’s relation to these architects is, in Stanford Anderson’s terms, one of critical conventionalism [2]. Wittgenstein builds on the conventions of pre-modern and Modern Viennese architecture, but re-interprets and re-appropriates each in a highly transformative and critical manner. The house’s design draws from the local design tradition of Vienna and wider Austria, making it historical without being historicist. The historical qualities of his architectural engagement are highlighted throughout the paper, particularly in part two, where a critical discourse on the architectural and interior qualities embodied in the Wittgenstein isparchitecture.com house is proffered. The significance of doing so is to demonstrate that Wittgenstein rejects not only ornament and opulence, as comes to define the Modern movement, but that he stands apart both aesthetically and intellectually from other Modernist architects practising in Vienna at the time. -

The Concept of 'Form of Life' in Wittgenstein's Thought

Langenthal Between Architecture and Language University of Ariel Edna Langenthal Between architecture and language as ‘form of life’ Abstract: Ludwig Wittgenstein’s philosophical writing is characterized by two main books, both acknowledged as major philosophical breakthroughs of the twentieth century: Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922), and Philosophical Investigations (published posthumously in 1953). Between these two texts, there is a shift in Wittgenstein’s thought on the structure and use of language, which is made evident by his decision to forego the idea of ‘pictorial form’ in favor of ‘life form.’ This transition, which allowed for a new understanding of the relation between the ethical and aesthetic aspects of Wittgenstein’s thought, greatly influenced Paul Engelmann’s understanding of architectural space. Following Wittgenstein’s writing, Engelmann claims that the concepts of ‘the beautiful’ and ‘the good’ are closely related, resulting in a distinct connection between what is beautiful and the concept of ‘form of life.’ In light of the influence that Wittgenstein’s writing had on Engelmann’s architecture, this paper examines the relation between architecture and language as ‘form of life,’ a connection which is suggested in Engelmann’s lecture ‘How to Build in the Kibbutz?’ in which Engelmann uses the term ‘form of life’ in reference to Wittgenstein’s writing on language. Biographical note: Dr Arch Edna Langenthal is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Ariel, School of Architecture and the founder and chief editor of Architext. Her research and teaching incorporate philosophical and ethical questions, emphasizing the link between the field of architecture and phenomenology. Edna is also an associate at Langenthal- Balasiano Architects, a firm specializing in the design and planning of public buildings. -

Darüber Muß Man Schweigen”

Philosophical Communications, Web Series, No. 32, pp. 82-99. Dept. of Philosophy, Göteborg University, Sweden ISSN 1652-0459 _______________________________________________________________ Ursus Philosophicus Essays dedicated to Björn Haglund on his sixtieth birthday _____________________________________________________________________________ Preprint, © 2004 Mats Furberg. All rights reserved _____________________________________________________________________________ Preprint, © 2004 Mats Furberg. All rights reserved “…darüber muß man schweigen” Mats Furberg Abstract Why does Wittgenstein hold in his first book that there are, or even must be, unsayables that nevertheless are possible to point to? And why is ethics ineffable? Several interpretations are given and rejected. The upshot is that the logical atomism set forth in the first five tenets of the book isn’t a necessary condition of the unsayability thesis. Wittgenstein seems to think that his ethics is tied to the idea of shifts of aspect, illustrated by the Necker cube. That shift is phenomenological and the phenomenology is “physicalistic”. I argue that in his considerations the cube has to enter in an uninterpreted form, as part of two brute facts. Is their logical Bild a thought (3) and a thought “der sinnvolle Satz” (4)? In a letter to a possible publisher of Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung,1 hence-forward LPA, Wittgenstein famously wrote,2 mein Werk bestehe aus zwei Teilen: aus dem, was hier vorliegt, und aus alledem, was ich nicht geschrieben habe. Und gerade dieser zweiten Teil ist der Wichtige. Es wird nämlich das Ethische durch mein Buch gleichsam von Innen her begrenzt; und ich bin überzeugt, daß es, streng, nur3 so zu begrenzen ist. Kurz, ich glaube: Alles das, was viele heute schwefeln, habe ich in meinem Buch festgelegt, in dem ich darüber schweige.