Poverty and the Picture Gallery [Paper]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hgstrust.Org London N11 1NP Tel: 020 8359 3000 Email: [email protected] (Add Character Appraisals’ in the Subject Line) Contents

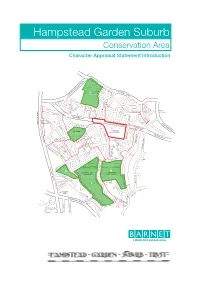

Hampstead Garden Suburb Conservation Area Character Appraisal Statement Introduction For further information on the contents of this document contact: Urban Design and Heritage Team (Strategy) Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust Planning, Housing and Regeneration 862 Finchley Road First Floor, Building 2, London NW11 6AB North London Business Park, tel: 020 8455 1066 Oakleigh Road South, email: [email protected] London N11 1NP tel: 020 8359 3000 email: [email protected] (add character appraisals’ in the subject line) Contents Section 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Hampstead Garden Suburb 5 1.2 Conservation areas 5 1.3 Purpose of a character appraisal statement 5 1.4 The Barnet unitary development plan 6 1.5 Article 4 directions 7 1.6 Area of special advertisement control 7 1.7 The role of Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust 8 1.8 Distinctive features of this character appraisal 8 Section 2 Location and uses 10 2.1 Location 10 2.2 Uses and activities 11 Section 3 The historical development of Hampstead Garden Suburb 15 3.1 Early history 15 3.2 Origins of the Garden Suburb 16 3.3 Development after 1918 20 3.4 1945 to the present day 21 Section 4 Spatial analysis 22 4.1 Topography 22 4.2 Views and vistas 22 4.3 Streets and open spaces 24 4.4 Trees and hedges 26 4.5 Public realm 29 Section 5 Town planning and architecture 31 Section 6 Character areas 36 Hampstead Garden Suburb Character Appraisal Introduction 5 Section 1 Introduction 1.1 Hampstead Garden Suburb Hampstead Garden Suburb is internationally recognised as one of the finest examples of early twentieth century domestic architecture and town planning. -

Henrietta Barnett: Co-Founder of Toynbee Hall, Teacher, Philanthropist and Social Reformer

Henrietta Barnett: Co-founder of Toynbee Hall, teacher, philanthropist and social reformer. by Tijen Zahide Horoz For a future without poverty There was always “something maverick, dominating, Roman about her, which is rarely found in women, though she was capable of deep feeling.” n 1884 Henrietta Barnett and her husband Samuel founded the first university settlement, Toynbee Hall, where Oxbridge students could become actively involved in helping to improve life in the desperately poor East End Ineighbourhood of Whitechapel. Despite her active involvement in Toynbee Hall and other projects, Henrietta has often been overlooked in favour of a focus on her husband’s struggle for social reform in East London. But who was the woman behind the man? Henrietta’s work left an indelible mark on the social history of London. She was a woman who – despite the obstacles of her time – accomplished so much for poor communities all over London. Driven by her determination to confront social injustice, she was a social reformer, a philanthropist, a teacher and a devoted wife. A shrewd feminist and political activist, Henrietta was not one to shy away from the challenges posed by a Victorian patriarchal society. As one Toynbee Hall settler recalled, Henrietta’s “irrepressible will was suggestive of the stronger sex”, and “there was always something maverick, dominating, Roman about her, which is rarely found in women, though she was capable of deep feeling.”1 (Cover photo): Henrietta in her forties. 1. Creedon, A. ‘Only a Woman’, Henrietta Barnett: Social Reformer and Founder of Hampstead Garden Suburb, (Chichester: Phillimore & Co. LTD, 2006) 3 A fourth sister had “married Mr James Hinton, the aurist and philosopher, whose thought greatly influenced Miss Caroline Haddon, who, as my teacher and my friend, had a dynamic effect on my then somnolent character.” The Early Years (Above): Henrietta as a young teenager. -

Hgstrust.Org London N11 1NP Tel: 020 8359 3000 Email: [email protected] (Add ‘Character Appraisals’ in the Subject Line) Contents

Hampstead Garden Suburb Central Square – Area 1 Character Appraisal For further information on the contents of this document contact: Urban Design and Heritage Team (Strategy) Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust Planning, Housing and Regeneration 862 Finchley Road First Floor, Building 2, London NW11 6AB North London Business Park, tel: 020 8455 1066 Oakleigh Road South, email: [email protected] London N11 1NP tel: 020 8359 3000 email: [email protected] (add ‘character appraisals’ in the subject line) Contents Section 1 Background historical and architectural information 5 1.1 Location and topography 5 1.2 Development dates and originating architect(s) and planners 5 1.3 Intended purpose of original development 5 1.4 Density and nature of the buildings. 5 Section 2 Overall character of the area 6 2.1 Principal positive features 7 2.2 Principal negative features 9 Section 3 The different parts of the main area in greater detail 11 3.1 Erskine Hill and North Square 11 3.2 Central Square, St. Jude’s, the Free Church and the Institute 14 3.3 South Square and Heathgate 17 3.4 Northway, Southway, Bigwood Court and Southwood Court 20 Map of area Hampstead Garden Suburb Central Square, Area 1 Character Appraisal 5 Character appraisal Section 1 Background historical and architectural information 1.1 Location and topography Central Square was literally at the centre of the ‘old’ suburb but, due to the further development of the Suburb in the 1920s and 1930s, it is now located towards the west of the Conservation Area. High on its hill, it remains the focal point of the Suburb. -

'How Lucky We Are to Live Here'*

of magnificent trees should not be and that the Trust’s expert witness considered. Hampstead Garden “did not make any great claims for LETTERS Suburb is a stunning conservation its architectural merit”. area and the tree in questions was I did not and do not understand Widecombe Way, N2 OHL well as visitors to our Suburb: part of Bigwood Nature Reserve why the Tribunal judge should 1) The extra rooms and spaces for according to the councils plans, it have been startled at what seems Sir, additional school activities and was also known as the tongue of to me to be a quite reasonable and Having earlier read “‘Inappropriate’ classes are indeed exceptional. It the ancient woodlands and covered moderately expressed opinion. There extension sends negative waves must be a pleasure to both teach by a tree preservation order, the are plenty of less distinguished around the Suburb” H&H, Sept 8, and learn in these well equipped sheer callousness of the appellants residential buildings on the Suburb. I decided to have a look at the new and inspiring rooms and areas. who were totally unable to prove In fact, that is the point I would be Henrietta Barnett School extension. 2) The outward design, whilst their case shows that fighting for grateful if you, Sir, would allow With respect, it is no monstrosity contemporary is not really sympathetic magnificent irreplaceable trees can me to make it and to draw 24 Ingram Avenue but a commendably thoughtful to its surroundings as an addition be successful. attention to its implications. construction. -

Henrietta Barnett School Hampstead Garden Suburb Case Study Case Study Henrietta Barnett School

library & learning Henrietta Barnett School Hampstead Garden Suburb Case Study Case Study Henrietta Barnett School Brief Solution The Henrietta Barnett School is a state grammar school for The key to the project was to match the ambition of the girls located in the Hampstead Garden Suburb Conservation refurbishment and historical importance of the school with its Area of North London. The library is situated in the main part educational imperatives, whilst offering high-quality products of the school, a Grade II* listed, early 20th Century building and excellent value for money. Because of this, a highly designed in the Queen Anne style by Sir Edwin Lutyens, and is bespoke solution was required. Julian Glover and Jonathan of heritage significance for its’ historic, architectural and social Hawkins from the FG Library design team worked closely value. with Architect Richard Paynter and a team from the school (including Head Del Cooke and Estates Manager Richard Barker Associates LLP were appointed to manage the Cain) to determine how the desired look could be achieved at refurbishment project, including the remodelling of the internal a realistic cost. Discussions focussed on the evaluation of a areas of the existing library. Alterations were designed to be range of materials, finishes and fabrics, the end objective being sympathetic to and compliment the character of the building the provision of the high quality products and levels of finish and the refurbishment, carried out by construction specialist within the available budget. T&B (Contractors) Ltd, needed to reflect the high quality of teaching and academic achievement at the school. -

A Sunny Summer Fun

www.hgs.org.uk Issue 135 · Summer 2018 Peter Cosmetatos Usual trouble- Suburb Time speaks at HB School makers show up at Capsule reveals Open Meeting, p3 Fun Day, p1&5 it’s secrets, p7 A sunny summer PETER McCLUSKIE Fun Day Sunday June 10 turned out to be the famous Styles family, and a fine sunny day which meant our regular entertainer Fizzie all the gazebos, stalls, picnic Lizzie occupied the young with tables and bunting went up in balloon modelling and drama. record time, thanks to the many Esra, of Painted Penguin, helpers and volunteers organised and her assistant had the usual by the ever hard-working RA long queues for face painting Events team. and glitter tattoos, while a team Once again our locally based of four donkeys worked hard all charity, All Dogs Matter, took afternoon giving small children over the corner of Central rides in the Square. Square near St Jude’s for its dog Arts and Crafts were strongly show and competitions for various featured this year and well-known categories, such as ‘Cutest Pup’ locals, Vera Moore, Lynda Cook and ‘Golden Oldie’. It was hardly and Diana Brahams from HGS surprising that there was a Art gave expert tuition and advice, record number of entries. which was very popular with the Local band Sound of the large numbers of children involved. Suburb provided live music The plant stall was kept during the afternoon for their busy with a constant stream of many fans. Traditional Punch plants going to good homes. and Judy was put on by one of (continued page 5) Punch & Judy never fails to attract a large crowd of enchanted children, affectionately watched over by loved ones Why you should join the Residents Association MICHAEL JACOBS to over 2,000 over the next five shown in the Suburb Directory. -

London and the Evolution of Suburbia a Tale of Two Suburbs by James

Architecture of Prosperity Series: London and the Evolution of Suburbia A Tale of Two Suburbs By James Fischelis 16 October 2014 * * * I’m going to talk about what we can learn about the future of London suburbs from what has already been built. I’ve chosen to focus on the London Borough of Barnet because it typifies much of suburban London: it’s made up of 33½ square miles of parks, gardens, houses, flats, offices and high streets. I’ll be looking in particular at two areas which, to my mind, illustrate the extremes of British suburban development over the past century. First is Hampstead Garden Suburb, built between 1909 - 1936, a haven of peace and tranquillity, neat hedges and middle class affluence. The second, 3½ miles north-west, is The Grahame Park Estate completed in 1971, and notorious as a drug-riddled, high crime, low income estate. Today it’s undergoing comprehensive demolition and redevelopment. Our story starts not in Barnet, or even North London, but in the East End - in Whitechapel. It was here, in the 1870s, that the ideas that led to the creation of Hampstead Garden Suburb were being dreamed of. Henrietta Barnett, the wife of a Whitechapel vicar, was appalled by the living conditions of the urban poor she saw all around her. Bad sanitation, overcrowding and disease were rife, and there was no escape from the black soot of the city, no green space. And so with the zeal of any right-minded Victorian ‘social reformer’, she set about creating a brave new world. -

Toynbee Hall: Further Reading

Toynbee Hall: Further Reading If you would like to know more about history of Toynbee Hall, the settlement movement and the East End of London, this is a select bibliography that will provide you with a starting point for further research. All books and offprints listed here are available through the Barnett Research Centre. Histories of Toynbee Hall: Henrietta Barnett, Canon Barnett: His Life, Work and Friends (1918) Asa Briggs and Anne Macartney, Toynbee Hall: The First Hundred Years (1984) Standish Meacham, Toynbee Hall and Social Reform 1880-1914: the Search for Community, (New Haven, 1987) Werner Picht, Toynbee Hall and the English Settlements, (1914) J.A.R. Pimlott, Toynbee Hall: Fifty Years of Social Progress, (1934) Studies of the Settlement Movement: Jane Addams, A Centennial Reader (New York, 1960) Mandy Ashworth, The Oxford House in Bethnal Green, 100 Years of Work in the Community (1984) Katharine Bradley, Bringing People Together: Bede House, Bermondsey and Rotherhithe 1938 – 2003 (2004) Katharine Bradley, ‘Creating Local Elites: the University Settlement Movement, National Elites and Citizenship in East London, 1884 – 1940’, in D.J. Wolffram (ed), Changing times: Elites and the dynamics of local politics (Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 2006) (offprint) Prudence Brown and Kitty Barnes, Connecting Neighbors: The role of settlement houses in building social bonds within communities (Chicago, 2001) Allen F. Davis, Spearheads for Reform: The Social Settlements and the Progressive Movement 1890 – 1914 (New York, 1967) Design History Forum, Osaka University, International Conferences Art and Welfare, Kurashiki 2005 Japan. 5th International Conference on the History of the Arts and Crafts Movement; 2nd International Conference on the History of the Settlement Movement, (Osaka, Japan, 2005) Mark Freeman, ‘“No finer school than a settlement”: the development of the educational settlement movement’, History of Education xxxi (2002), pp. -

Preserving the Historic Garden Suburb: Case Studies from London and New York

Suburban Sustainability Volume 2 Issue 1 Article 1 2014 Preserving the Historic Garden Suburb: Case Studies from London and New York Jeffrey A. Kroessler John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/subsust Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Recommended Citation Kroessler, Jeffrey A. (2014) "Preserving the Historic Garden Suburb: Case Studies from London and New York," Suburban Sustainability: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. https://www.doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/2164-0866.2.1.1 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/subsust/vol2/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Environmental Sustainability at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Suburban Sustainability by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kroessler: Preserving the Historic Garden Suburb Introduction In all the discussions of sustainability, historic preservation rarely makes an appearance. Energy efficiency, recycled materials, green roofs, LEED certification, solar power and windmills, even bike racks – all are popularized as acceptable elements of sustainable architecture. Economic justice, environmentalism, and social justice are the primary concerns of sustainability advocates. Environmental planning addresses the preservation of open space and greenbelts, but rarely the preservation of the built environment (Young 2002). Restoring or maintaining historic buildings is generally not counted as green by environmental advocates. But really, the greenest building is the one that is already built. -

Download (958Kb)

LJMU Research Online Matthews-Jones, LM Settling at Home: Gender and Class in the Room Biographies of Toynbee Hall, 1883-1914 http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/id/eprint/7622/ Article Citation (please note it is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from this work) Matthews-Jones, LM (2017) Settling at Home: Gender and Class in the Room Biographies of Toynbee Hall, 1883-1914. Victorian Studies, 60 (1). pp. 29-52. ISSN 1527-2052 LJMU has developed LJMU Research Online for users to access the research output of the University more effectively. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LJMU Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of the record. Please see the repository URL above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information please contact [email protected] http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/ Settling at Home: Gender and Class in the Room Biographies of Toynbee Hall, 1883- 1914 Lucinda Matthews-Jones fig 1: Images from Robert A. Woods, “The Social Awaking in London” in Robert A. Woods (ed.),The Poor in Great Cities: Their Problems and What is Doing to Solve Them (Charles Scribner’s & Son, 1895). -

Canon Barnett and the First Thirty Years of Toynbee Hall Abel, Emily K

Canon Barnett and the first thirty years of Toynbee Hall Abel, Emily K. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/jspui/handle/123456789/1332 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] c ' Abstract This thesis is a study of the changing role which Toynbee Hell, the first university settlement, played in East London between 1884 and 1914. The first chapter presents a brief biography of Sainiel Augustus Barnett, the founder end ft ret warden of the settlement, and analyzes his social thought in relation to the beliefs which were current in Britain during the period. The second chapter discusses the founding of the settlement, its organiza-. tion&. structure and the aims which underlay its early v&rk. The third chapter, concentrating on Iliree residents, C.R. Ashbee, .H. Beveridge and T. dmund Harvey, shows the way in which subsequent settlement workers reformulated these aims In accordance with their own social and economic views. The subsequent chapters discuss the accomp1Ishnnts of the settlement in various fields. The fourth shows that Toynbee Hell's educational program, iich was largely en attempt to work out Matthew Arnold's theory of culture, left little i.mpact on the life of E85t London. -

Hotblack Dixon

Suburb welcomes new Alyth appoints new Principal Rabbi Mark Goldsmith has been rabbinate in 1996 from the Leo programmes are really outstanding.” School Head appointed Principal Rabbi of the Baeck College, the training seminary A graduate of Manchester University, already have close contacts with North Western Reform Synagogue for rabbis in both the Reform where he pursued a degree in local organisations – such as the (Alyth Gardens). He succeeds and Liberal Jewish movements. management sciences, Rabbi Nick Maines Organ Scholarship Rabbi Dr. Charles Emanuel who Rabbi Goldsmith began his Goldsmith has been active in which we set up with St Jude’s will continue to be involved in rabbinic career at Woodford many cross-communal activities, Church and our girls always enjoy synagogue affairs as Rabbi Progressive Synagogue. “I am and has served as the Chairman contributing to the St Jude’s Proms. Emeritus. very excited about my new role,” of the Liberal Judaism Rabbinic We are also delighted to be Prior to assuming his new Rabbi Goldsmith said. “Alyth is Conference from 2003-2005. involved with and supporting position, Rabbi Goldsmith was one of the most dynamic Jewish He has been particularly the Suburb Centenary for which Rabbi at Finchley Progressive congregations in this country and active in the study of Jewish we will be hosting the town Synagogue. He achieved his its social, cultural and education business ethics. planning, architectural and environmental conference and assisting with various other events. Fellowship Club Two years ago we formed For more years than most can Samuel Barnett and named after of weekly activities, whether The Henrietta Barnett Choral remember, there has been an their friend and fellow reformer physical (keep fit, Tai Chi, Society, which has been an annual summer visit to the Arnold Toynbee, Toynbee Hall croquet) or mental (talks, film outstanding success.