Lucinda Matthews-‐Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toynbee Hall's Olympic Heritage

[Image] Baron Pierre de Coubertin, 1915. Source: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress) Toynbee Hall’s Olympic Heritage Toynbee Hall traces its historic connection to the founder of the modern day Olympics. by Shahana Subhan Begum [Left] Samuel Barnett with residents in front of the In June 1886 a young French gentleman Lecture Hall entrance, in his twenties, with an impressive Toynbee Hall c. late 1890’s moustache, visited Toynbee Hall. The Frenchman was Pierre de Coubertin (1863-1937), who in 1896 revived the Olympic Games in its modern form. Today, Coubertin is most known for his role in the revival of the Olympics, but he described himself first and foremost as Coubertin’s interest in education and It was during these visits that Coubertin an educational reformer and it was this sport led him to England where sport first heard of Toynbee Hall. Toynbee work that brought him to Toynbee Hall. had become an integral part of the Hall was founded by Reverend Samuel curriculum in several leading public Barnett and his wife Henrietta Barnett Pierre Frédy de Coubertin was born in schools. During his first visit to England in 1884, in memory of their friend Paris in 1863 to an aristocratic family. in 1883, Coubertin toured a number of Arnold Toynbee (1852- 1883). He turned his back on the military leading English educational institutions career planned for him, in order including Harrow, Eton and Rugby Before his untimely death, Toynbee to engage with social issues and schools and Oxford and Cambridge had been a young Oxford historian pursue educational reform in France. -

Hgstrust.Org London N11 1NP Tel: 020 8359 3000 Email: [email protected] (Add Character Appraisals’ in the Subject Line) Contents

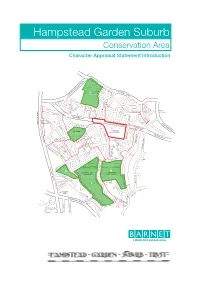

Hampstead Garden Suburb Conservation Area Character Appraisal Statement Introduction For further information on the contents of this document contact: Urban Design and Heritage Team (Strategy) Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust Planning, Housing and Regeneration 862 Finchley Road First Floor, Building 2, London NW11 6AB North London Business Park, tel: 020 8455 1066 Oakleigh Road South, email: [email protected] London N11 1NP tel: 020 8359 3000 email: [email protected] (add character appraisals’ in the subject line) Contents Section 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Hampstead Garden Suburb 5 1.2 Conservation areas 5 1.3 Purpose of a character appraisal statement 5 1.4 The Barnet unitary development plan 6 1.5 Article 4 directions 7 1.6 Area of special advertisement control 7 1.7 The role of Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust 8 1.8 Distinctive features of this character appraisal 8 Section 2 Location and uses 10 2.1 Location 10 2.2 Uses and activities 11 Section 3 The historical development of Hampstead Garden Suburb 15 3.1 Early history 15 3.2 Origins of the Garden Suburb 16 3.3 Development after 1918 20 3.4 1945 to the present day 21 Section 4 Spatial analysis 22 4.1 Topography 22 4.2 Views and vistas 22 4.3 Streets and open spaces 24 4.4 Trees and hedges 26 4.5 Public realm 29 Section 5 Town planning and architecture 31 Section 6 Character areas 36 Hampstead Garden Suburb Character Appraisal Introduction 5 Section 1 Introduction 1.1 Hampstead Garden Suburb Hampstead Garden Suburb is internationally recognised as one of the finest examples of early twentieth century domestic architecture and town planning. -

Henrietta Barnett: Co-Founder of Toynbee Hall, Teacher, Philanthropist and Social Reformer

Henrietta Barnett: Co-founder of Toynbee Hall, teacher, philanthropist and social reformer. by Tijen Zahide Horoz For a future without poverty There was always “something maverick, dominating, Roman about her, which is rarely found in women, though she was capable of deep feeling.” n 1884 Henrietta Barnett and her husband Samuel founded the first university settlement, Toynbee Hall, where Oxbridge students could become actively involved in helping to improve life in the desperately poor East End Ineighbourhood of Whitechapel. Despite her active involvement in Toynbee Hall and other projects, Henrietta has often been overlooked in favour of a focus on her husband’s struggle for social reform in East London. But who was the woman behind the man? Henrietta’s work left an indelible mark on the social history of London. She was a woman who – despite the obstacles of her time – accomplished so much for poor communities all over London. Driven by her determination to confront social injustice, she was a social reformer, a philanthropist, a teacher and a devoted wife. A shrewd feminist and political activist, Henrietta was not one to shy away from the challenges posed by a Victorian patriarchal society. As one Toynbee Hall settler recalled, Henrietta’s “irrepressible will was suggestive of the stronger sex”, and “there was always something maverick, dominating, Roman about her, which is rarely found in women, though she was capable of deep feeling.”1 (Cover photo): Henrietta in her forties. 1. Creedon, A. ‘Only a Woman’, Henrietta Barnett: Social Reformer and Founder of Hampstead Garden Suburb, (Chichester: Phillimore & Co. LTD, 2006) 3 A fourth sister had “married Mr James Hinton, the aurist and philosopher, whose thought greatly influenced Miss Caroline Haddon, who, as my teacher and my friend, had a dynamic effect on my then somnolent character.” The Early Years (Above): Henrietta as a young teenager. -

In the Mid 1880'S, Issues of the Working Poor Caused by Urbanization, Industrialization and Immigration Were a Catalyst For

SETTLE ENT OVE ENT In the mid 1880's, issues of the working poor caused One of the first three university settlement houses Not limited to Chicago, by 1913 there were 413 by urbanization, industrialization and immigration in England, Toynbee Hall saw a number of American settlement houses throughout the United States, were a catalyst for the Settlement Movement. visitors in its early years. Most famously, Jane Addams, including Boston. Two local Boston leaders, Robert Envisioned by Arnold Toynbee, a tutor at Balliol suffragette, abolitionist, pacifist and first American A. Woods and Vida Dutton Scudder visited Toynbee College, England, and his colleagues, the Movement woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, found Hall as religious students, and later brought the was a revolutionary and humanistic approach to social inspiration when she Settlement Movement to Boston. Woods became work which brought the social worker face to face visited Toynbee Hall in the head resident at Boston's first Settlement, with life in urban slums. Settlement workers would 1887-88. Jane Addams Andover House, in 1892. Woods, however, had live in settlement houses providing both education became attracted a contentious relationship with the immigrants and social services. Workers at Toynbee Hall, located in to settlement work he intended to help, often seeing them as London's East Side and named for Arnold Toynbee by through the faith of resistant to assimilation. Woods developed a friend and colleague Canon Samuel Barnett, practiced her father, a devout difficult relationship with the community, often Barnett's visionary mission "to learn as much as to Quaker. -

Hgstrust.Org London N11 1NP Tel: 020 8359 3000 Email: [email protected] (Add ‘Character Appraisals’ in the Subject Line) Contents

Hampstead Garden Suburb Central Square – Area 1 Character Appraisal For further information on the contents of this document contact: Urban Design and Heritage Team (Strategy) Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust Planning, Housing and Regeneration 862 Finchley Road First Floor, Building 2, London NW11 6AB North London Business Park, tel: 020 8455 1066 Oakleigh Road South, email: [email protected] London N11 1NP tel: 020 8359 3000 email: [email protected] (add ‘character appraisals’ in the subject line) Contents Section 1 Background historical and architectural information 5 1.1 Location and topography 5 1.2 Development dates and originating architect(s) and planners 5 1.3 Intended purpose of original development 5 1.4 Density and nature of the buildings. 5 Section 2 Overall character of the area 6 2.1 Principal positive features 7 2.2 Principal negative features 9 Section 3 The different parts of the main area in greater detail 11 3.1 Erskine Hill and North Square 11 3.2 Central Square, St. Jude’s, the Free Church and the Institute 14 3.3 South Square and Heathgate 17 3.4 Northway, Southway, Bigwood Court and Southwood Court 20 Map of area Hampstead Garden Suburb Central Square, Area 1 Character Appraisal 5 Character appraisal Section 1 Background historical and architectural information 1.1 Location and topography Central Square was literally at the centre of the ‘old’ suburb but, due to the further development of the Suburb in the 1920s and 1930s, it is now located towards the west of the Conservation Area. High on its hill, it remains the focal point of the Suburb. -

'How Lucky We Are to Live Here'*

of magnificent trees should not be and that the Trust’s expert witness considered. Hampstead Garden “did not make any great claims for LETTERS Suburb is a stunning conservation its architectural merit”. area and the tree in questions was I did not and do not understand Widecombe Way, N2 OHL well as visitors to our Suburb: part of Bigwood Nature Reserve why the Tribunal judge should 1) The extra rooms and spaces for according to the councils plans, it have been startled at what seems Sir, additional school activities and was also known as the tongue of to me to be a quite reasonable and Having earlier read “‘Inappropriate’ classes are indeed exceptional. It the ancient woodlands and covered moderately expressed opinion. There extension sends negative waves must be a pleasure to both teach by a tree preservation order, the are plenty of less distinguished around the Suburb” H&H, Sept 8, and learn in these well equipped sheer callousness of the appellants residential buildings on the Suburb. I decided to have a look at the new and inspiring rooms and areas. who were totally unable to prove In fact, that is the point I would be Henrietta Barnett School extension. 2) The outward design, whilst their case shows that fighting for grateful if you, Sir, would allow With respect, it is no monstrosity contemporary is not really sympathetic magnificent irreplaceable trees can me to make it and to draw 24 Ingram Avenue but a commendably thoughtful to its surroundings as an addition be successful. attention to its implications. construction. -

Henrietta Barnett School Hampstead Garden Suburb Case Study Case Study Henrietta Barnett School

library & learning Henrietta Barnett School Hampstead Garden Suburb Case Study Case Study Henrietta Barnett School Brief Solution The Henrietta Barnett School is a state grammar school for The key to the project was to match the ambition of the girls located in the Hampstead Garden Suburb Conservation refurbishment and historical importance of the school with its Area of North London. The library is situated in the main part educational imperatives, whilst offering high-quality products of the school, a Grade II* listed, early 20th Century building and excellent value for money. Because of this, a highly designed in the Queen Anne style by Sir Edwin Lutyens, and is bespoke solution was required. Julian Glover and Jonathan of heritage significance for its’ historic, architectural and social Hawkins from the FG Library design team worked closely value. with Architect Richard Paynter and a team from the school (including Head Del Cooke and Estates Manager Richard Barker Associates LLP were appointed to manage the Cain) to determine how the desired look could be achieved at refurbishment project, including the remodelling of the internal a realistic cost. Discussions focussed on the evaluation of a areas of the existing library. Alterations were designed to be range of materials, finishes and fabrics, the end objective being sympathetic to and compliment the character of the building the provision of the high quality products and levels of finish and the refurbishment, carried out by construction specialist within the available budget. T&B (Contractors) Ltd, needed to reflect the high quality of teaching and academic achievement at the school. -

The Frontline Interview with Katherine Norman

The Frontline Interview with Katherine Norman In this edition, Katherine interviews Sian Williams, Head of National Services at Toynbee Hall. the development of the new financial them to tackle social injustice. Tower health needs assessment and impact Hamlets is characterised by high rates measurement MAP Tool, our financial of child poverty, worklessness, mortality Sian Williams capability and literacy programmes, and and overcrowding. The majority of the our systems thinking work with service 10,000 people we work with each year providers from a wide range of sectors. live on very low incomes, have multiple Q. Can you tell us a little about your I also represent Toynbee Hall at relevant needs, low aspirations or poor health. We work history and how you came to work policy meetings, conferences and good work with them to identify the services at Toynbee Hall? practice events, oversee the development to improve their lives, and provide an of national services, such as our training opportunity for them to take action. and consultancy services, and make A. After studying languages at Durham Our work is themed across four different sure we are contributing to and shaping University, I joined the Foreign and programme areas: Advice, Youth and the financial health policy and practice Commonwealth Office in 1993. In 1997 Community, Financial Inclusion and agenda across the UK. I receive a lot of I was posted to Hong Kong initially and Wellbeing. Our service users are diverse, requests to speak at events and to brief I stayed with the FCO through a posting and include young people, older people, people on the world and work of financial to Beijing and a range of jobs back in new migrants, people who are financially inclusion. -

Jane Addams and Peace Education for Socia Justice

Jane Addams and the Promotion of Peace and Social Justice Among the Masses Charles F. Howlett, Ph.D., Molloy College INTRODUCTION Jane Addams was the first American female to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931. She was a co-recipient with Nicholas Murray Butler, president of Columbia University. Addams was a social reformer, founder of Hull House in Chicago, and the leader of the women’s peace movement in the first half of the twentieth century. She authored a number of books, including her popular autobiography, Twenty Years at Hull House. Addams is considered one of America’s foremost female intellectual leaders? and a pioneer in the practical application of progressive education ideas to everyday life. BACKGROUND Born on September 6, 1860 in Cedarville, Illinois, and later educated at Rockville Female Seminary in Illinois (renamed Rockville Women’s College), Addams later established herself as one of the leading females in the areas of social reform, women’s suffrage, and war opponent. A powerful writer and thinker in her own right, Addams’ ideas were largely influenced by University of Chicago philosopher and educator John Dewey. In the 1890s, before he moved on to Columbia University, Dewey’s pragmatism opened Addams’ moralistic and religious training to the hard fact that conflict was a reality of everyday life, but one capable of transforming social disruption into progress and harmony. In the late 1890s and at the turn of the new century, Addams quickly understood the role that powerful financiers and political privilege played in maintaining class divisions. The bitter class warfare of the last decades of the nineteenth century, along with economic depressions, convinced Addams that benevolent change based on peace and justice education was possible to improve American society and the state of the world. -

Petite Et Grande Histoire Des Centres Sociaux "Pour Espérer, Pour Aller De L’Avant, Il Faut Aussi Savoir D’Où L’On Vient"

Petite et grande histoire des centres sociaux "Pour espérer, pour aller de l’avant, il faut aussi savoir d’où l’on vient". Fernand BRAUDEL, historien Révolution industrielle Exode rural développement misère : pas de logement, salaire bas Développement dans les pays industrialisés : Europe, EU du christianisme humaniste Les principes du « settlement movement » anglais • L'objectif du mouvement était de réunir les riches et les pauvres pour vivre plus étroitement ensemble dans une communauté solidaire au sein de la société. • Le principal but était la création de «maisons d'accueil» dans les zones urbaines pauvres des grandes villes, dans lesquelles des bénévoles "issus des classes moyennes et aisées" vivraient, dans l'espoir de partager les connaissances et la culture, et d'atténuer la pauvreté de leurs voisins à faibles revenus 1884 TOYNBEE HALL (Londres-GB) Premier centre social Né du « Setlement movement » Samuel et Henrietta BARNETT Vicaire de l’Eglise d’Angleterre Apprendre les uns des autres dans un face-à-face constructif. 1889 HULL HOUSE (Chicago- USA) Trois femmes d’exception ! Jane ADAMS, philosophe, Ellen GATES Mary CROZET SMITH (à droite) sociologue, pacifiste engagée STARR, co- Résidente et donatrice Prix Nobel de la Paix 1931 fondatrice de Hull Créatrice de la maison des House adolescents et de l’école des arts Le settlement façon Jane ADAMS • Résidence, Recherche, Réforme. • « la collaboration avec les habitants du quartier, la mise en place d'une étude sérieuse et poussée sur les causes de la pauvreté et de la dépendance, la communication des faits au public, et des débats sur la réforme législative et sociale ». -

Boston's Settlement Housing: Social Reform in an Industrial City Meg Streiff Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Boston's settlement housing: social reform in an industrial city Meg Streiff Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Streiff, Meg, "Boston's settlement housing: social reform in an industrial city" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 218. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/218 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. BOSTON’S SETTLEMENT HOUSING: SOCIAL REFORM IN AN INDUSTRIAL CITY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Meg Streiff B.A., City College of New York (CUNY), 1992 M.A., San Diego State University, 1994 August 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Certainly, there are many individuals who helped me complete this project, far too many to include here. First and foremost, I’d like to thank the reference librarians (in particular, Sarah Hutcheon) at the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University for their eagerness to help me locate archival materials on Denison House. Likewise, I’d like to thank the archivists (especially, David Klaassen and Linnea Anderson) at the Social Welfare History Archives, University of Minnesota, for assisting me with the voluminous South End House data as well as offering useful local information on where to dine, what museums to visit, and which buses carried passengers fastest through the city of Minneapolis. -

Arnold Toynbee by Celia Toynbee

Arnold Toynbee by Celia Toynbee For a future without poverty The Toynbee family tree Joseph Toynbee Pioneering Harriet Holmes otolaryngologist 1823–1897 1815–1866 Gilbert Murray Arnold Toynbee Harry Valpy Lady Mary Classicist and Economic historian Toynbee Howard public intellectual 1852–1883 1861–1941 1865–1956 1866–1957 Arnold J. Toynbee Universal historian Rosalind Murray 1889–1975 1890–1967 Philip Toynbee Jean Lawrence Antony Harry Writer and Anne Powell Constance Toynbee Toynbee journalist 1920-2004 Asquith 1914–1939 1922–2002 1916–1981 1921 Arnold Toynbee Celia Toynbee Arnold Toynbee Polly Toynbee Josephine (1 of 6 siblings) Journalist Toynbee 1948 uch is known about iconic figures such as Samuel Barnett, William 1946 Beveridge and Clement Attlee who shaped the early years of Toynbee Hall. MLess however is known about Arnold Toynbee and his relationship with the Settlement, he had a short but meaningful life and was admired by the founders so much so that Henrietta Barnett suggested it be named after him. 1 rnold Toynbee died aged 30 in 1883 and it is ironic that he died without knowing his legacy. It was during a memorial service to him on 10th March A1884 that Henrietta noticed that Balliol Chapel was packed with men who had come in loving memory and she felt were filled by the aspiration to copy Arnold in caring so much for those who had fallen by the wayside. “As I sat on that Sunday afternoon among the crowd of strong-brained, clean-living men, the thought flashed to me let us call the Settlement Toynbee Hall...our new Settlement received its name before a brick was laid or the plans concluded…” Joseph Toynbee Harriet Holmes, Mrs J Toynbee Arnold was one of the keenest of a group of like-minded, educated, young men Who was Arnold Toynbee? who worked with the Barnetts when they first arrived in Whitechapel at St Jude’s Parish church in 1873.