Abstract This Thesis Is a Study of the Changing Role Which

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1982, Boyd, Octavia Hill OCR C.Pdf

'Anyone interested in women, religion, sodal action, biography, or history will find this book valuable. And if you perceive that that list includes just about everyone, you are correct.' - Ellen Miller Casey, Best Sellers 'As a theologian as weil as a feminist Dr Boyd might have a double·edged axe to grind, but the grinding if any is quieto She has written a thoughtful, sensible, non-propagandising and rather entertaining book, striking a good balance ~\\\NE BUll between factual narrative and interpretation' -KathIeen Nott, Observer ~S ~ The three women who had the greatest effect on sodal policy in Britain in the .A. nineteenth century were josephine Butler, Octavia Hili and Florence Nightingale. In an era when most women were confined to the kitchen and the salon, these three moved confidently into positions of world leadership. ..OCTAVIA HILL josephine Butler raised opposition to the state regulation of prostitution and _w...... confronted the root issues of poverty and of dvil rights for wamen. Octavia Hili --~. - artist, teacher and great conservationist - enabled thousands of families to meet the dislocations of the industrial revolution and created a new profession, that of the sodal worker Florence Nightingale not only shattered precedent by establishing a training-school for nurses, she also pioneered work in the use of FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE statistical analysis, and her practicality and passionate urgency effected radical reforms in medical practice and public health. These women atti-ibuted their sodal vision and the impetus for their vocation to their religious faith. Rejecting the constraints on women's work imposed by conventional religion, they found in the gospels ground for radical action. -

Toynbee Hall's Olympic Heritage

[Image] Baron Pierre de Coubertin, 1915. Source: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress) Toynbee Hall’s Olympic Heritage Toynbee Hall traces its historic connection to the founder of the modern day Olympics. by Shahana Subhan Begum [Left] Samuel Barnett with residents in front of the In June 1886 a young French gentleman Lecture Hall entrance, in his twenties, with an impressive Toynbee Hall c. late 1890’s moustache, visited Toynbee Hall. The Frenchman was Pierre de Coubertin (1863-1937), who in 1896 revived the Olympic Games in its modern form. Today, Coubertin is most known for his role in the revival of the Olympics, but he described himself first and foremost as Coubertin’s interest in education and It was during these visits that Coubertin an educational reformer and it was this sport led him to England where sport first heard of Toynbee Hall. Toynbee work that brought him to Toynbee Hall. had become an integral part of the Hall was founded by Reverend Samuel curriculum in several leading public Barnett and his wife Henrietta Barnett Pierre Frédy de Coubertin was born in schools. During his first visit to England in 1884, in memory of their friend Paris in 1863 to an aristocratic family. in 1883, Coubertin toured a number of Arnold Toynbee (1852- 1883). He turned his back on the military leading English educational institutions career planned for him, in order including Harrow, Eton and Rugby Before his untimely death, Toynbee to engage with social issues and schools and Oxford and Cambridge had been a young Oxford historian pursue educational reform in France. -

Hgstrust.Org London N11 1NP Tel: 020 8359 3000 Email: [email protected] (Add Character Appraisals’ in the Subject Line) Contents

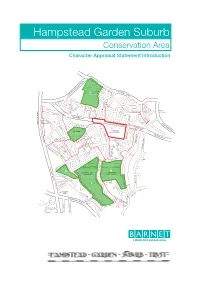

Hampstead Garden Suburb Conservation Area Character Appraisal Statement Introduction For further information on the contents of this document contact: Urban Design and Heritage Team (Strategy) Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust Planning, Housing and Regeneration 862 Finchley Road First Floor, Building 2, London NW11 6AB North London Business Park, tel: 020 8455 1066 Oakleigh Road South, email: [email protected] London N11 1NP tel: 020 8359 3000 email: [email protected] (add character appraisals’ in the subject line) Contents Section 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Hampstead Garden Suburb 5 1.2 Conservation areas 5 1.3 Purpose of a character appraisal statement 5 1.4 The Barnet unitary development plan 6 1.5 Article 4 directions 7 1.6 Area of special advertisement control 7 1.7 The role of Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust 8 1.8 Distinctive features of this character appraisal 8 Section 2 Location and uses 10 2.1 Location 10 2.2 Uses and activities 11 Section 3 The historical development of Hampstead Garden Suburb 15 3.1 Early history 15 3.2 Origins of the Garden Suburb 16 3.3 Development after 1918 20 3.4 1945 to the present day 21 Section 4 Spatial analysis 22 4.1 Topography 22 4.2 Views and vistas 22 4.3 Streets and open spaces 24 4.4 Trees and hedges 26 4.5 Public realm 29 Section 5 Town planning and architecture 31 Section 6 Character areas 36 Hampstead Garden Suburb Character Appraisal Introduction 5 Section 1 Introduction 1.1 Hampstead Garden Suburb Hampstead Garden Suburb is internationally recognised as one of the finest examples of early twentieth century domestic architecture and town planning. -

Henrietta Barnett: Co-Founder of Toynbee Hall, Teacher, Philanthropist and Social Reformer

Henrietta Barnett: Co-founder of Toynbee Hall, teacher, philanthropist and social reformer. by Tijen Zahide Horoz For a future without poverty There was always “something maverick, dominating, Roman about her, which is rarely found in women, though she was capable of deep feeling.” n 1884 Henrietta Barnett and her husband Samuel founded the first university settlement, Toynbee Hall, where Oxbridge students could become actively involved in helping to improve life in the desperately poor East End Ineighbourhood of Whitechapel. Despite her active involvement in Toynbee Hall and other projects, Henrietta has often been overlooked in favour of a focus on her husband’s struggle for social reform in East London. But who was the woman behind the man? Henrietta’s work left an indelible mark on the social history of London. She was a woman who – despite the obstacles of her time – accomplished so much for poor communities all over London. Driven by her determination to confront social injustice, she was a social reformer, a philanthropist, a teacher and a devoted wife. A shrewd feminist and political activist, Henrietta was not one to shy away from the challenges posed by a Victorian patriarchal society. As one Toynbee Hall settler recalled, Henrietta’s “irrepressible will was suggestive of the stronger sex”, and “there was always something maverick, dominating, Roman about her, which is rarely found in women, though she was capable of deep feeling.”1 (Cover photo): Henrietta in her forties. 1. Creedon, A. ‘Only a Woman’, Henrietta Barnett: Social Reformer and Founder of Hampstead Garden Suburb, (Chichester: Phillimore & Co. LTD, 2006) 3 A fourth sister had “married Mr James Hinton, the aurist and philosopher, whose thought greatly influenced Miss Caroline Haddon, who, as my teacher and my friend, had a dynamic effect on my then somnolent character.” The Early Years (Above): Henrietta as a young teenager. -

In the Mid 1880'S, Issues of the Working Poor Caused by Urbanization, Industrialization and Immigration Were a Catalyst For

SETTLE ENT OVE ENT In the mid 1880's, issues of the working poor caused One of the first three university settlement houses Not limited to Chicago, by 1913 there were 413 by urbanization, industrialization and immigration in England, Toynbee Hall saw a number of American settlement houses throughout the United States, were a catalyst for the Settlement Movement. visitors in its early years. Most famously, Jane Addams, including Boston. Two local Boston leaders, Robert Envisioned by Arnold Toynbee, a tutor at Balliol suffragette, abolitionist, pacifist and first American A. Woods and Vida Dutton Scudder visited Toynbee College, England, and his colleagues, the Movement woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, found Hall as religious students, and later brought the was a revolutionary and humanistic approach to social inspiration when she Settlement Movement to Boston. Woods became work which brought the social worker face to face visited Toynbee Hall in the head resident at Boston's first Settlement, with life in urban slums. Settlement workers would 1887-88. Jane Addams Andover House, in 1892. Woods, however, had live in settlement houses providing both education became attracted a contentious relationship with the immigrants and social services. Workers at Toynbee Hall, located in to settlement work he intended to help, often seeing them as London's East Side and named for Arnold Toynbee by through the faith of resistant to assimilation. Woods developed a friend and colleague Canon Samuel Barnett, practiced her father, a devout difficult relationship with the community, often Barnett's visionary mission "to learn as much as to Quaker. -

English Women and the Late-Nineteenth Century Open Space Movement

English Women and the Late-Nineteenth Century Open Space Movement Robyn M. Curtis August 2016 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Australian National University Thesis Certification I declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History at the Australian National University, is wholly my own original work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged and has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Robyn M. Curtis Date …………………… ………………… Abstract During the second half of the nineteenth century, England became the most industrialised and urbanised nation on earth. An expanding population and growing manufacturing drove development on any available space. Yet this same period saw the origins of a movement that would lead to the preservation and creation of green open spaces across the country. Beginning in 1865, social reforming groups sought to stop the sale and development of open spaces near metropolitan centres. Over the next thirty years, new national organisations worked to protect and develop a variety of open spaces around the country. In the process, participants challenged traditional land ownership, class obligations and gender roles. There has been very little scholarship examining the work of the open space organisations; nor has there been any previous analysis of the specific membership demographics of these important groups. This thesis documents and examines the four organisations that formed the heart of the open space movement (the Commons Preservation Society, the Kyrle Society, the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association and the National Trust). It demonstrates connections between philanthropy, gender and space that have not been explored previously. -

(Crimson) 1. Caroline Gardens, Grade II Listed. London's Largest Co

GOLDSMITHS Places of Interest NORTH - Arts and Crafts ride (crimson) 1. Caroline Gardens, grade II listed. London’s largest complex of almshouses, built 1833 onwards, with quadrangle, gardens and a large chapel, which now houses the Asylum arts organisation. 2. Peckham Library - Will Alsop’s iconic and gravity-defying structure, which won the Stirling Prize in 2000 and helped kickstart the regeneration of Peckham. 3. A charming 22 acre conservation area of Arts & Crafts-style housing, early 1900s, built by Octavia Hill, social reformer and co-founder of the National Trust. 4. T34 - A brightly painted and graffiti-bombed Russian tank defends a disused piece of land. 5. The Jam Factory - an impressive housing redevelopment of the huge redbrick former Hartley’s jam factory, built 1900. Bermondsey antiques market (a) - a cornucopia of vintage wares - is just up the road. 6. White Cube, a major gallery in a superbly converted 1970s warehouse. Further along now-trendy Bermondsey Street is the Fashion & Textile Museum (a). 7. One of the most (in)famous graffiti artworks by Banksy, still in situ: one (hooded) man and his (Keith Haring-esque) dog. 8. Dilston Grove - a well respected arts space in a run down former church in Southwark Park. 9. A grade II listed brick and concrete former Swedish Mission, with detached steeple, which was used by Scandinavian sailors who worked the nearby Greenland Docks (part of the Maritime ride). EAST - Maritime ride (teal) 1. Surrey Quays: 10 pin bowling, cinema and shopping complex. 2. One of the last remaining buildings, now residential, in what was the first Royal Navy dockyard, founded by Henry VIII in 1513. -

Hgstrust.Org London N11 1NP Tel: 020 8359 3000 Email: [email protected] (Add ‘Character Appraisals’ in the Subject Line) Contents

Hampstead Garden Suburb Central Square – Area 1 Character Appraisal For further information on the contents of this document contact: Urban Design and Heritage Team (Strategy) Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust Planning, Housing and Regeneration 862 Finchley Road First Floor, Building 2, London NW11 6AB North London Business Park, tel: 020 8455 1066 Oakleigh Road South, email: [email protected] London N11 1NP tel: 020 8359 3000 email: [email protected] (add ‘character appraisals’ in the subject line) Contents Section 1 Background historical and architectural information 5 1.1 Location and topography 5 1.2 Development dates and originating architect(s) and planners 5 1.3 Intended purpose of original development 5 1.4 Density and nature of the buildings. 5 Section 2 Overall character of the area 6 2.1 Principal positive features 7 2.2 Principal negative features 9 Section 3 The different parts of the main area in greater detail 11 3.1 Erskine Hill and North Square 11 3.2 Central Square, St. Jude’s, the Free Church and the Institute 14 3.3 South Square and Heathgate 17 3.4 Northway, Southway, Bigwood Court and Southwood Court 20 Map of area Hampstead Garden Suburb Central Square, Area 1 Character Appraisal 5 Character appraisal Section 1 Background historical and architectural information 1.1 Location and topography Central Square was literally at the centre of the ‘old’ suburb but, due to the further development of the Suburb in the 1920s and 1930s, it is now located towards the west of the Conservation Area. High on its hill, it remains the focal point of the Suburb. -

H R Trevor-Roper Vs. Arnold Toynbee: a Post-Christian Religion

H R Trevor-Roper vs. Arnold Toynbee: A post-Christian Religion and a new Messiah in an age of reconciliation? Frederick Hale1 (University of Pretoria) ABSTRACT H R Trevor-Roper vs. Arnold Toynbee: A post-Christian Religion and a new Messiah in an age of reconciliation? That the twentieth century witnessed massive secularisation in Europe and certain other parts of the world is beyond dispute, as is the fact that the general phenomenon of religion and its role as a factor shaping history remain potent on a broad, international scale. There is no consensus, however, about the future place or status of Western Christian civilisation or “Christendom” in a shrinking and pluralistic world also struggling with the challenge of reconciliation. During the 1950s two controversial giants of British historiography, Arnold Toynbee and H R Trevor-Roper clashed on this issue. Their severe differences of opinion were conditioned in part by the Cold War, general retreat of imperialism from Africa and Asia, and the growth of the economic, military, and political power of previously colonised or otherwise subjugated nations. 1 INTRODUCTION The vicissitudes of the twentieth century, especially the two world wars which splashed the blood of tens of millions of victims across its first half, convinced many European scholars that Western or Christian civilisation might be in its final phase. Their predictions of its demise were not entirely novel; similar prognostications had been made well before 1900. However, increasing fragmentation, chauvinistic nationa- lisms, the clash of ideologies, the march of secularisation, the lack of tolerance and reconciliation, and other tendencies gave renewed cur- rency to the general view that Christendom, at least in its European manifestation, had largely had its day. -

'How Lucky We Are to Live Here'*

of magnificent trees should not be and that the Trust’s expert witness considered. Hampstead Garden “did not make any great claims for LETTERS Suburb is a stunning conservation its architectural merit”. area and the tree in questions was I did not and do not understand Widecombe Way, N2 OHL well as visitors to our Suburb: part of Bigwood Nature Reserve why the Tribunal judge should 1) The extra rooms and spaces for according to the councils plans, it have been startled at what seems Sir, additional school activities and was also known as the tongue of to me to be a quite reasonable and Having earlier read “‘Inappropriate’ classes are indeed exceptional. It the ancient woodlands and covered moderately expressed opinion. There extension sends negative waves must be a pleasure to both teach by a tree preservation order, the are plenty of less distinguished around the Suburb” H&H, Sept 8, and learn in these well equipped sheer callousness of the appellants residential buildings on the Suburb. I decided to have a look at the new and inspiring rooms and areas. who were totally unable to prove In fact, that is the point I would be Henrietta Barnett School extension. 2) The outward design, whilst their case shows that fighting for grateful if you, Sir, would allow With respect, it is no monstrosity contemporary is not really sympathetic magnificent irreplaceable trees can me to make it and to draw 24 Ingram Avenue but a commendably thoughtful to its surroundings as an addition be successful. attention to its implications. construction. -

Henrietta Barnett School Hampstead Garden Suburb Case Study Case Study Henrietta Barnett School

library & learning Henrietta Barnett School Hampstead Garden Suburb Case Study Case Study Henrietta Barnett School Brief Solution The Henrietta Barnett School is a state grammar school for The key to the project was to match the ambition of the girls located in the Hampstead Garden Suburb Conservation refurbishment and historical importance of the school with its Area of North London. The library is situated in the main part educational imperatives, whilst offering high-quality products of the school, a Grade II* listed, early 20th Century building and excellent value for money. Because of this, a highly designed in the Queen Anne style by Sir Edwin Lutyens, and is bespoke solution was required. Julian Glover and Jonathan of heritage significance for its’ historic, architectural and social Hawkins from the FG Library design team worked closely value. with Architect Richard Paynter and a team from the school (including Head Del Cooke and Estates Manager Richard Barker Associates LLP were appointed to manage the Cain) to determine how the desired look could be achieved at refurbishment project, including the remodelling of the internal a realistic cost. Discussions focussed on the evaluation of a areas of the existing library. Alterations were designed to be range of materials, finishes and fabrics, the end objective being sympathetic to and compliment the character of the building the provision of the high quality products and levels of finish and the refurbishment, carried out by construction specialist within the available budget. T&B (Contractors) Ltd, needed to reflect the high quality of teaching and academic achievement at the school. -

The Frontline Interview with Katherine Norman

The Frontline Interview with Katherine Norman In this edition, Katherine interviews Sian Williams, Head of National Services at Toynbee Hall. the development of the new financial them to tackle social injustice. Tower health needs assessment and impact Hamlets is characterised by high rates measurement MAP Tool, our financial of child poverty, worklessness, mortality Sian Williams capability and literacy programmes, and and overcrowding. The majority of the our systems thinking work with service 10,000 people we work with each year providers from a wide range of sectors. live on very low incomes, have multiple Q. Can you tell us a little about your I also represent Toynbee Hall at relevant needs, low aspirations or poor health. We work history and how you came to work policy meetings, conferences and good work with them to identify the services at Toynbee Hall? practice events, oversee the development to improve their lives, and provide an of national services, such as our training opportunity for them to take action. and consultancy services, and make A. After studying languages at Durham Our work is themed across four different sure we are contributing to and shaping University, I joined the Foreign and programme areas: Advice, Youth and the financial health policy and practice Commonwealth Office in 1993. In 1997 Community, Financial Inclusion and agenda across the UK. I receive a lot of I was posted to Hong Kong initially and Wellbeing. Our service users are diverse, requests to speak at events and to brief I stayed with the FCO through a posting and include young people, older people, people on the world and work of financial to Beijing and a range of jobs back in new migrants, people who are financially inclusion.