What Do You Do with the Garbage? New York City's Progressive Era Sanitary Reforms and Their Impact on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Report on the City of New York's Existing and Possible Tree Canopy

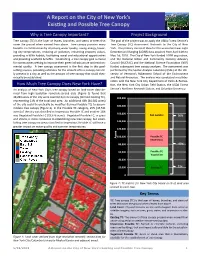

A Report on the City of New York’s Existing and Possible Tree Canopy Why is Tree Canopy Important? Project Background Tree canopy (TC) is the layer of leaves, branches, and stems of trees that The goal of the project was to apply the USDA Forest Service’s cover the ground when viewed from above. Tree canopy provides many Tree Canopy (TC) Assessment Protocols to the City of New benefits to communities by improving water quality, saving energy, lower- York. The primary source of data for this assessment was Light ing city temperatures, reducing air pollution, enhancing property values, Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) data acquired from April 14th to providing wildlife habitat, facilitating social and educational opportunities May 1st, 2010. The City of New York funded LiDAR acquisition, and providing aesthetic benefits. Establishing a tree canopy goal is crucial and the National Urban and Community Forestry Advisory for communities seeking to improve their green infrastructure and environ- Council (NUCFAC) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) mental quality. A tree canopy assessment is the first step in this goal- funded subsequent tree canopy analyses. The assessment was setting process, providing estimates for the amount of tree canopy current- performed by the Spatial Analysis Laboratory (SAL) at the Uni- ly present in a city as well as the amount of tree canopy that could theo- versity of Vermont’s Rubenstein School of the Environment retically be established. and Natural Resources. The analysis was conducted in collabo- ration with the New York City Department of Parks & Recrea- How Much Tree Canopy Does New York Have? tion, the New York City Urban Field Station, the USDA Forest An analysis of New York City’s tree canopy based on land-cover data de- Service’s Northern Research Station, and Columbia University. -

Natural Resources Group Forest Restoration Team Planting Report Fall 2010

Natural Resources Group Forest Restoration Team Planting Report Fall 2010 Dear Parkie, The Natural Resources Group (NRG) moved closer to our PlaNYC goal of planting over 400,000 trees throughout the city. This past fall we planted over 30,000 trees in 2 properties in all five boroughs. Our current tally stands at 222,188. Furthermore, we planted over 7,000 shrubs and over 4,000 herbaceous plants Our primary goal is to create and restore multi-story forests, bringing back the ecological richness of our region. Healthy multi-story forests provide cleaner air, cleaner water, and increased biodiversity. NRG again hosted the Million Trees volunteer day. Volunteers and Parks’ staff planted 21,806 trees altogether. Without volunteers and the support of the Agency, and our institutional and community partners, NRG would not reach its planting goals. Below is a summary of fall 2010. • Containerized trees planted by the Forest Restoration Team: 27,130 (2009: 26,139) • Containerized trees planted through contractors: 4,332 (2009: 9,652) • Balled & burlapped trees planted through contractors: 58 (2009: 267) • Containerized shrubs planted by the Forest Restoration Team: 5,701 (2009: 4,626) • Containerized shrubs planted through contractors: 1,492 (2009: 0) • Herbaceous plugs planted by the Forest Restoration Team: 4,540 (2009: 18,528) • Hosted 11 volunteer events with a total of 341 volunteers (2009: 32, 468) Sincerely, Tim Wenskus Deputy Director Natural Resources Group Total Plants Planted Trees 31,520 Shrubs 7,193 Herbaceous 4,540 Grand Total 43,253 -

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2000

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2000 Floyd Bennett Field Gateway NRA - Jamaica Bay Unit Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Floyd Bennett Field Gateway NRA - Jamaica Bay Unit Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields are entered into a national database. In addition, -

New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan

NEW YORK CITY CoMPREHENSWE WATERFRONT PLAN Reclaiming the City's Edge For Public Discussion Summer 1992 DAVID N. DINKINS, Mayor City of New lVrk RICHARD L. SCHAFFER, Director Department of City Planning NYC DCP 92-27 NEW YORK CITY COMPREHENSIVE WATERFRONT PLAN CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMA RY 1 INTRODUCTION: SETTING THE COURSE 1 2 PLANNING FRA MEWORK 5 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 5 LEGAL CONTEXT 7 REGULATORY CONTEXT 10 3 THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 17 WATERFRONT RESOURCES AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE 17 Wetlands 18 Significant Coastal Habitats 21 Beaches and Coastal Erosion Areas 22 Water Quality 26 THE PLAN FOR THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 33 Citywide Strategy 33 Special Natural Waterfront Areas 35 4 THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 51 THE EXISTING PUBLIC WATERFRONT 52 THE ACCESSIBLE WATERFRONT: ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES 63 THE PLAN FOR THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 70 Regulatory Strategy 70 Public Access Opportunities 71 5 THE WORKING WATERFRONT 83 HISTORY 83 THE WORKING WATERFRONT TODAY 85 WORKING WATERFRONT ISSUES 101 THE PLAN FOR THE WORKING WATERFRONT 106 Designation Significant Maritime and Industrial Areas 107 JFK and LaGuardia Airport Areas 114 Citywide Strategy fo r the Wo rking Waterfront 115 6 THE REDEVELOPING WATER FRONT 119 THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT TODAY 119 THE IMPORTANCE OF REDEVELOPMENT 122 WATERFRONT DEVELOPMENT ISSUES 125 REDEVELOPMENT CRITERIA 127 THE PLAN FOR THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT 128 7 WATER FRONT ZONING PROPOSAL 145 WATERFRONT AREA 146 ZONING LOTS 147 CALCULATING FLOOR AREA ON WATERFRONTAGE loTS 148 DEFINITION OF WATER DEPENDENT & WATERFRONT ENHANCING USES -

Representative SCS Landfill Closure Projects Facility Name State Size (Acres)

Representative SCS Landfill Closure Projects Size State (acres) Facility Name Nabors Landfill, Class 4 and Areas 1-2, 1-3 AR 48 City of Oracle Page, Trowbridge Ranch Landfill Closure AZ 4 City of Tucson Los Reales Landfill, West Side Closure AZ 30 Navajo County, Lone Pine Landfill AZ 60 Pinal County, Page-Trowbridge Ranch Landfill AZ 3.2 Butte County, Neal Road Landfill CA 33 City of Auburn Landfill CA 20 City of Los Angeles Bishops Canyon Landfill CA 45 City of Modesto Carpenter Road Landfill, Partial Clean Closure CA 38 City of Riverside, Tequesquite Landfill CA 40 City of Sacramento Dellar Property Closure CA 28 County of Mercer Highway 59 Closure CA 88 Placer County Eastern Regional Landfill CA 3 Potrero Hills Landfill CA 150 Salinas Valley Solid Waste Authority, Lewis Road Landfill CA 15 Sonoma Central Landfill, LF-1 Closure CA 85 Stanislaus County, Fink Road Landfill CA 18 West Contra Costa CA 60 Bayside Landfill, Closure FL 30 DeSoto County Landfill, Zone 1 FL 3 Escambia County Beulah Road Landfill FL 100 Glades County Landfill, Final Closure FL 7 Gulf Coast Landfill, Phase III Closure FL 15 Hillsborough County Pleasant Grove Class I Landfill FL 11 Immokalee Landfill, Closure FL 24 Lake County Lady Lake Landfill FL 2 Medley Landfill, Phases 1A, 1B, 2, 3, 4, 5 Closures FL 84 Monarch Hill Landfill, Phases 1-7 Closures FL 110 Naples Landfill, Naples, Phase 2 Closure FL 11 Okeechobee Landfill, Phases 1-5 Closures FL 98 Polk County North Central Class III Landfill FL 11 Royal Oaks Ranch, Titusville, Final Closure FL 30 SCMM Landfill, Phase 1 Closure FL 23 Volusia County Plymouth Ave. -

Reel-It-In-Brooklyn

REEL IT IN! BROOKLYN Fish Consumption Education Project in Brooklyn ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: This research and outreach project was developed by Going Coastal, Inc. Team members included Gabriel Rand, Zhennya Slootskin and Barbara La Rocco. Volunteers were vital to the execution of the project at every stage, including volunteers from Pace University’s Center for Community Action and Research, volunteer translators Inessa Slootskin, Annie Hongjuan and Bella Moharreri, and video producer Dave Roberts. We acknowledge support from Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz and funding from an Environmental Justice Research Impact Grant of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Photos by Zhennya Slootskin, Project Coordinator. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Study Area 3. Background 4. Methods 5. Results & Discussion 6. Conclusions 7. Outreach Appendix A: Survey List of Acronyms: CSO Combined Sewer Overflow DEC New York State Department of Environmental Conservation DEP New York City Department of Environmental Protection DOH New York State Department of Health DPR New York City Department of Parks & Recreation EPA U.S. Environmental Protection Agency GNRA Gateway National Recreation Area NOAA National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Agency OPRHP New York State Office of Parks, Recreation & Historic Preservation PCBs Polychlorinated biphenyls WIC Women, Infant and Children program Reel It In Brooklyn: Fish Consumption Education Project Page 2 of 68 Abstract Brooklyn is one of America’s largest and fastest growing multi‐ethnic coastal counties. All fish caught in the waters of New York Harbor are on mercury advisory. Brooklyn caught fish also contain PCBs, pesticides, heavy metals, many more contaminants. The waters surrounding Brooklyn serve as a source of recreation, transportation and, for some, food. -

“Forgotten by God”: How the People of Barren Island Built a Thriving Community on New York City's Garbage

“Forgotten by God”: How the People of Barren Island Built a Thriving Community on New York City’s Garbage ______________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History Brooklyn College ______________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Miriam Sicherman Thesis Advisor: Michael Rawson Spring 2018 Table of Contents Abstract 1 Acknowledgments 2 Introduction 3 Chapter 1: Early History, Landscape, and Population 22 Chapter 2: Outsiders and Insiders 35 Chapter 3: Work 53 Chapter 4: Recreation and Religion 74 Chapter 5: Municipal Neglect 84 Chapter 6: Law and Order 98 Chapter 7: Education 112 Chapter 8: The End of Barren Island 134 Conclusion 147 Works Cited 150 1 Abstract This thesis describes the everyday life experiences of residents of Barren Island, Brooklyn, from the 1850s until 1936, demonstrating how they formed a functioning community under difficult circumstances. Barren Island is located in Jamaica Bay, between Sheepshead Bay and the Rockaway Peninsula. During this time period, the island, which had previously been mostly uninhabited, was the site of several “nuisance industries,” primarily garbage processing and animal rendering. Because the island was remote and often inaccessible, the workers, mostly new immigrants and African-Americans, were forced to live on the island, and very few others lived there. In many ways the islanders were neglected and ignored by city government and neighboring communities, except as targets of blame for the bad smells produced by the factories. In the absence of adequate municipal attention, islanders were forced to create their own community norms and take care of their own needs to a great extent. -

To Download Three Wonder Walks

Three Wonder Walks (After the High Line) Featuring Walking Routes, Collections and Notes by Matthew Jensen Three Wonder Walks (After the High Line) The High Line has proven that you can create a des- tination around the act of walking. The park provides a museum-like setting where plants and flowers are intensely celebrated. Walking on the High Line is part of a memorable adventure for so many visitors to New York City. It is not, however, a place where you can wander: you can go forward and back, enter and exit, sit and stand (off to the side). Almost everything within view is carefully planned and immaculately cultivated. The only exception to that rule is in the Western Rail Yards section, or “W.R.Y.” for short, where two stretch- es of “original” green remain steadfast holdouts. It is here—along rusty tracks running over rotting wooden railroad ties, braced by white marble riprap—where a persistent growth of naturally occurring flora can be found. Wild cherry, various types of apple, tiny junipers, bittersweet, Queen Anne’s lace, goldenrod, mullein, Indian hemp, and dozens of wildflowers, grasses, and mosses have all made a home for them- selves. I believe they have squatters’ rights and should be allowed to stay. Their persistence created a green corridor out of an abandoned railway in the first place. I find the terrain intensely familiar and repre- sentative of the kinds of landscapes that can be found when wandering down footpaths that start where streets and sidewalks end. This guide presents three similarly wild landscapes at the beautiful fringes of New York City: places with big skies, ocean views, abun- dant nature, many footpaths, and colorful histories. -

BROOKLYN COMMUNITY DISTRICT 18 Oversight Block Lot Facility Name Facility Address Facility Type Capacity / Type Agency

Selected Facilities and Program Sites Page 1 of 23 in New York City, release 2015 BROOKLYN COMMUNITY DISTRICT 18 Oversight Block Lot Facility Name Facility Address Facility Type Capacity / Type Agency SCHOOLS Public Elementary and Secondary Schools 8158 35FRESH CREEK SCHOOL (THE) 875 Williams Ave Elementary School ‐ Public 198 Children NYC DOE 8160 22PS 114 RYDER ELEMENTARY 1077 Remsen Ave Elementary School ‐ Public 622 Children NYC DOE 8256 1PS 115 DANIEL MUCATEL SCHOOL 1500 E 92 St Elementary School ‐ Public 1167 Children NYC DOE 7786 1PS 119 AMERSFORT 3829 Ave K Elementary School ‐ Public 420 Children NYC DOE 7849 1PS 203 FLOYD BENNETT SCHOOL 5101 Ave M Elementary School ‐ Public 779 Children NYC DOE 8484 1PS 207 ELIZABETH G LEARY 4011 Fillmore Ave Elementary School ‐ Public 1272 Children NYC DOE 7706 1PS 222 KATHERINE R SNYDER 3301 Quentin Rd Elementary School ‐ Public 869 Children NYC DOE 8464 1PS 236 MILL BASIN 6302 Ave U Elementary School ‐ Public 578 Children NYC DOE 7758 1PS 251 PAERDEGAT 1037 E 54 St Elementary School ‐ Public 571 Children NYC DOE 8158 35PS 260 BREUCKELEN 875 Williams Ave Elementary School ‐ Public 28 Children NYC DOE 8329 250PS 272 CURTIS ESTABROOK 101‐24 Seaview Ave Elementary School ‐ Public 567 Children NYC DOE 8034 1PS 276 LOUIS MARSHALL 1070 E 83 St Elementary School ‐ Public 775 Children NYC DOE 8590 650PS 277 GERRITSEN BEACH 2529 Gerritsen Ave Elementary School ‐ Public 459 Children NYC DOE 8230 1PS 279 HERMAN SCHREIBER 1070 E 104 St Elementary School ‐ Public 535 Children NYC DOE 8393 1PS 312 BERGEN -

New York City Audubon's Harbor Herons Project: 2018 Nesting Survey

NEW YORK CITY AUDUBON’S HARBOR HERONS PROJECT: 2018 NESTING SURVEY REPORT 11 December 2018 Prepared for: New York City Audubon Kathryn Heintz, Executive Director 71 W. 23rd Street, Suite 1523 New York, NY 10010 Tel. 212-691-7483 www.nycaudubon.org Prepared by: Tod Winston, Research Assistant New York City Audubon 71 W. 23rd Street, Suite 1523 New York, NY 10010 Tel. 917-698-1892 [email protected] 1 New York City Audubon’s Conservation Programs are made possible by the leadership support of The Leon Levy Foundation. Support for the Harbor Herons Nesting Surveys comes from New York City Audubon major donor contributions, including the generosity of Elizabeth Woods and Charles Denholm, and from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. This report should be cited as follows: Winston, T. 2018. New York City Audubon’s Harbor Herons Project: 2018 Nesting Survey Report. New York City Audubon, New York, NY. 2 Abstract New York City Audubon’s Harbor Herons Project Nesting Survey of the New York/New Jersey Harbor and surrounding waterways was conducted between 15 May and 26 June 2018. This report principally summarizes long-legged wading bird, cormorant, and gull nesting activity observed on selected harbor islands, and also includes surveys of selected mainland sites and aids to navigation. Seven species of long-legged wading birds were observed nesting on eight of fifteen islands surveyed, on Governors Island, and at several mainland sites, while one additional species was confirmed as nesting exclusively at a mainland site. Surveyed wading bird species, hereafter collectively referred to as waders, included (in order of decreasing abundance) Black-crowned Night-Heron, Great Egret, Snowy Egret, Glossy Ibis, Yellow-crowned Night-Heron, Little Blue Heron, Tricolored Heron, and Great Blue Heron. -

Reading the Landscape: Citywide Social Assessment of New York City Parks and Natural Areas in 2013-2014

Reading the Landscape: Citywide Social Assessment of New York City Parks and Natural Areas in 2013-2014 Social Assessment White Paper No. 2 March 2016 Prepared by: D. S. Novem Auyeung Lindsay K. Campbell Michelle L. Johnson Nancy F. Sonti Erika S. Svendsen Table of Contents Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 8 Study Area ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Methods ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Data Collection .................................................................................................................................... 12 Data Analysis........................................................................................................................................ 15 Findings ........................................................................................................................................ 16 Park Profiles ........................................................................................................................................ -

Page 1 of 3 Comments of Brooklyn Borough President Eric L. Adams In

Comments of Brooklyn Borough President Eric L. Adams In Response to the Proposed Scope of Work for the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the East River Ferry—September 28, 2015 My name is Eric L. Adams, and I represent Brooklyn’s 2.6 million residents as Borough President. Thank you for the opportunity to testify today at the scoping hearing of the Environmental Impact Assessment for citywide ferry service. I am a long-time supporter of ferry service as a means to improve transit accessibility, reduce congestion, catalyze economic development, and connect communities. As a result, I support the efforts of New York City’s Economic Development Corporation to implement a Citywide Ferry Service (CFS) that would provide an affordable and convenient transit option to residents in otherwise transit-isolated neighborhoods. The introduction of a Southern Brooklyn local ferry route would provide reliable service to Bay Ridge, Sunset Park, Red Hook, Brooklyn Heights, and DUMBO communities. In addition, the Rockaway ferry would include express ferry service to Bay Ridge. Both of these additions would offer resilient transit service to communities in dire need of more transportation options. I also believe that the local route would have subsequent potential to add an additional stop in Sunset Park in proximity to the Bush Terminal complex, and that the Rockaway route could subsequently be modified after initial success to add service to the Canarsie Pier, the marina opposite Aviator Sports in Dead Horse Bay, Plumb Beach, and Coney Island (possibly West 21st Street landing in Coney Island Creek). Even though I support this effort, I also offer the following comments for the Draft Scope: Site Selection I have several concerns about the ferry landing sites included in the project description, particularly the appropriateness of the proposed landing in Red Hook.