Reel-It-In-Brooklyn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Explore Gowanus

park helps to capture and and capture to helps park sponge and Gowanus Canal Conservancy. Conservancy. Canal Gowanus and banks of the Gowanus Canal. The The Canal. Gowanus the of banks Department of Sanitation of New York York New of Sanitation of Department the street end rain gardens along the the along gardens rain end street the with a collaborative effort between the the between effort collaborative a with is about 1,800 square feet surrounding surrounding feet square 1,800 about is green space. This green space began began space green This space. green open to the public called sponge park. It It park. sponge called public the to open flow tanks. The Salt Lot also provides provides also Lot Salt The tanks. flow Self-Guided Tour Self-Guided commercial building esplanade that is is that esplanade building commercial - over sewage combined two the for site This site of new luxury residential and and residential luxury new of site This final stop. This is the second proposed proposed second the is This stop. final ou have now reached your fifth stop. stop. fifth your reached now have ou Y t the dead end you have reached the the reached have you end dead the t A 7 THE SALT LOT SALT THE 5 ESPLANADE 365 BOND ST BOND 365 ESPLANADE hood starts to change here. change to starts hood park along the edge. the along park - neighbor the as note Take past. the water. Here you can see the sponge sponge the see can you Here water. GOWANUS point source of pollution in the canal in in canal the in pollution of source point ing lot and towards the edge of the the of edge the towards and lot ing like much now but this was a major major a was this but now much like - park Foods Whole the through Walk gas processing plants. -

2017 Community Action Plan for Coney Island Creek & Parklands

Making Waves 2017 community action plan Coney Island Creek & Parklands Coney Island Creek & Parklands Cover photo: Coney island Creek. Credit: Charles Denson. Inside cover: City Parks Foundation Coastal Classroom students working together in Kaiser Park. All photos in this plan by the Partnerships for Parks Catalyst Program, unless otherwise noted. Table of Contents Working In Partnership Community leadership in restoring the Creek Coney Island Creek: History & Challenges Reversing a century of neglect Water Quality Restoring and protecting the Creek Public Engagement and Education Community building for a lifetime relationship with our environment Access and On-Water Programming A community that connects with its water cares for its water Resiliency and Flood Protection Protecting our community and enhancing natural assets Blueways and Greenways Connecting Coney Island to New York City: ferry service, paddling, and biking Connecting community to Coney Island Creek. Members of Coney Island Explorers and Coney Island Girl Scouts on a NYC Parks guided trip to discover and monitor Creating Community in our Parks and Open Spaces horseshoe crabs. Citizen science projects are part of the community plan to gauge the Sustaining thriving parks and public spaces for generations health of the Creek estuary. Photo: Eddie Mark Coney Island Creek & Parklands Making Waves Community Action Plan Page 3 WORKING IN PARTNERSHIP Community leadership in restoring the Creek CONEY ISLAND BEAUTIFICATION PROJECT is an environmental THE CONEY ISLAND HISTORY PROJECT, founded in 2004, is a 501(c)(3) not- organization that came into existence to help our community respond to the huge for-profit organization that aims to increase awareness of Coney Island's legendary impacts of Superstorm Sandy. -

Newtown Creek Project Packet

NEWTOWN CREEK PROJECT PACKET Name: ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTORY READING: Encyclopedia. “Newtown Creek.” The Encyclopedia of New York City. 2nd ed. 2010. Print. Adaptation Newtown Creek is a tributary of the East River. It extends inland for a distance of 3.5 miles, including a number of canals into Brooklyn, and it is the boundary between Brooklyn and Queens. The creek was the route by which European colonists first reached Maspeth in 1642. During the American Revolution the British spent the winter near the creek. Commercial vessels and small boats sailed the creek in the early nineteenth century. About 1860 the first oil and coal oil refineries opened along the banks and began dumping sludge and acids into the water; sewers were built to accommodate the growing neighborhoods of Williamsburg and Greenpoint and discharged their wastes directly into the creek, which by 1900 was known for pollution and foul odors. The water corroded the paint on the undersides of ships, and noxious deposits were left on the banks by the tides. High-level bridges were built from 1903 (some remain). State and city commissions sought unsuccessfully to improve the creek as it became of the busiest commercial waterways in the country, second only to the Mississippi River. The creek was dredged constantly and widened by the federal government to accommodate marine traffic; the creek’s natural depth was between 4 and 12 feet. After World War II the creek’s importance as a shipping route decreased, but it continued to be the site of many industrial plants. During the 1940s and 1950s, leaks at oil refineries including ExxonMobil and ChevronTexaco precipitated one of the largest underground oil spills in history. -

Pre-Remedial Activities Presentation for the Coney

WELCOME! THE MEETING WILL BEGIN SHORTLY. to ask question and to un/mute mic share comments to raise hand to leave the call to turn on/off video Microsoft Teams Meeting Controls For technical assistance contact Stephen McBay to view full screen [email protected] Thank you! to view live caption EPA’s Pre-Remedial Activities at Coney Island Creek Agenda Introductions What EPA Is Doing In Your Community Where To Find More Information Questions and Comments Conclusion EPA PREREMEDIAL ACTIVITIES AT CONEY ISLAND CREEK | 3 On the Call Donette Samuel, Community Involvement Coordinator Shereen Kandil, Community Affairs Team Lead Denise Zeno, Site Assessment Manager Angela Carpenter, Branch Chief EPA PREREMEDIAL ACTIVITIES AT CONEY ISLAND CREEK | 4 Introductions EPA PREREMEDIAL ACTIVITIES AT CONEY ISLAND CREEK | 5 Background EPA received a request to perform a Preliminary Assessment from a community member. EPA PREREMEDIAL ACTIVITIES AT CONEY ISLAND CREEK | 6 Preliminary Assessment Discover site in Review historical Evaluate the potential Determine if future EPA’s database (SEMS) information for a hazardous investigation is needed substance release EPA PREREMEDIAL ACTIVITIES AT CONEY ISLAND CREEK | 7 Site Inspection Site visit Develop sampling Sample site Transport Analyze samples Record lab strategy samples to lab results into for analysis a report WE ARE HERE EPA PREREMEDIAL ACTIVITIES AT CONEY ISLAND CREEK | 8 Analyze Samples Types of sample: surface water and sediment samples Contaminants under examination: Volatile organic compounds (VOC), Semivolatile organic compounds (SVOC), Pesticides, Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and Metals EPA PREREMEDIAL ACTIVITIES AT CONEY ISLAND CREEK | 9 Sampling Photo credit: Charles Denson Executive Director of the Coney Island History Project EPA PREREMEDIAL ACTIVITIES AT CONEY ISLAND CREEK | 10 How does EPA’s role differ from other active Agencies and Organizations in the region? NEW YORK CITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION FEDRAL AGENCY WORKING TO PROTECT HUMAN HEALTH AND NONPROFIT CORPORATION PROMOTING THE ENVIRONMENT. -

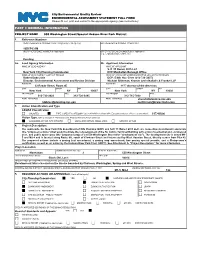

550 Washington Street/Special Hudson River Park District 1

City Environmental Quality Review ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT STATEMENT FULL FORM Please fill out, print and submit to the appropriate agency (see instructions) PART I: GENERAL INFORMATION PROJECT NAME 550 Washington Street/Special Hudson River Park District 1. Reference Numbers CEQR REFERENCE NUMBER (To Be Assigned by Lead Agency) BSA REFERENCE NUMBER (If Applicable) 16DCP031M ULURP REFERENCE NUMBER (If Applicable) OTHER REFERENCE NUMBER(S) (If Applicable) (e.g., Legislative Intro, CAPA, etc.) Pending 2a. Lead Agency Information 2b. Applicant Information NAME OF LEAD AGENCY NAME OF APPLICANT SJC 33 Owner 2015 LLC New York City Planning Commission DCP Manhattan Borough Office NAME OF LEAD AGENCY CONTACT PERSON NAME OF APPLICANT’S REPRESENTATIVE OR CONTACT PERSON Robert Dobruskin DCP: Edith Hsu-Chen (212-720-3437) Director, Environmental Assessment and Review Division Michael Sillerman, Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel LLP ADDRESS ADDRESS 22 Reade Street, Room 4E 1177 Avenue of the Americas CITY STATE ZIP CITY STATE ZIP New York NY 10007 New York NY 10036 TELEPHONE FAX TELEPHONE FAX 212-720-3423 212-720-3495 212-715-7838 EMAIL ADDRESS EMAIL ADDRESS [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3. Action Classification and Type SEQRA Classification UNLISTED TYPE I; SPECIFY CATEGORY (see 6 NYCRR 617.4 and NYC Executive Order 91 of 1977, as amended): 617.4(6)(v) Action Type (refer to Chapter 2, “Establishing the Analysis Framework” for guidance) LOCALIZED ACTION, SITE SPECIFIC LOCALIZED ACTION, SMALL AREA GENERIC ACTION 4. Project Description: The applicants, the New York City Department of City Planning (DCP) and SJC 33 Owner 2015 LLC, are requesting discretionary approvals (the “proposed actions”) that would facilitate the redevelopment of the St. -

July 8 Grants Press Release

CITY PARKS FOUNDATION ANNOUNCES 109 GRANTS THROUGH NYC GREEN RELIEF & RECOVERY FUND AND GREEN / ARTS LIVE NYC GRANT APPLICATION NOW OPEN FOR PARK VOLUNTEER GROUPS Funding Awarded For Maintenance and Stewardship of Parks by Nonprofit Organizations and For Free Live Performances in Parks, Plazas, and Gardens Across NYC July 8, 2021 - NEW YORK, NY - City Parks Foundation announced today the selection of 109 grants through two competitive funding opportunities - the NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund and GREEN / ARTS LIVE NYC. More than ever before, New Yorkers have come to rely on parks and open spaces, the most fundamentally democratic and accessible of public resources. Parks are critical to our city’s recovery and reopening – offering fresh air, recreation, and creativity - and a crucial part of New York’s equitable economic recovery and environmental resilience. These grant programs will help to support artists in hosting free, public performances and programs in parks, plazas, and gardens across NYC, along with the nonprofit organizations that help maintain many of our city’s open spaces. Both grant programs are administered by City Parks Foundation. The NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund will award nearly $2M via 64 grants to NYC-based small and medium-sized nonprofit organizations. Grants will help to support basic maintenance and operations within heavily-used parks and open spaces during a busy summer and fall with the city’s reopening. Notable projects supported by this fund include the Harlem Youth Gardener Program founded during summer 2020 through a collaboration between Friends of Morningside Park Inc., Friends of St. Nicholas Park, Marcus Garvey Park Alliance, & Jackie Robinson Park Conservancy to engage neighborhood youth ages 14-19 in paid horticulture along with the Bronx River Alliance’s EELS Youth Internship Program and Volunteer Program to invite thousands of Bronxites to participate in stewardship of the parks lining the river banks. -

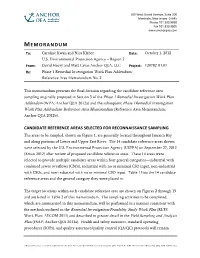

Phase 1 Remedial Investigation Work Plan Addendum: Reference Area Memorandum No

305 West Grand Avenue, Suite 300 Montvale, New Jersey 07645 Phone 201.930.9890 Fax 201.930.9805 www.anchorqea.com MEMORANDUM To: Caroline Kwan and Nica Klaber Date: October 1, 2012 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency – Region 2 From: David Haury and Matt Cavas Anchor QEA, LLC Project: 120782-01.01 Re: Phase 1 Remedial Investigation Work Plan Addendum: Reference Area Memorandum No. 2 This memorandum presents the final decision regarding the candidate reference area sampling originally proposed in Section 3 of the Phase 1 Remedial Investigation Work Plan Addendum (WPA; Anchor QEA 2012a) and the subsequent Phase 1Remedial Investigation Work Plan Addendum: Reference Area Memorandum (Reference Area Memorandum; Anchor QEA 2012b). CANDIDATE REFERENCE AREAS SELECTED FOR RECONNAISSANCE SAMPLING The areas to be sampled, shown on Figure 1, are generally located throughout Jamaica Bay and along portions of Lower and Upper East River. The 14 candidate reference areas shown were selected by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) on September 27, 2012 (Kwan 2012) after review of proposed candidate reference areas. These 14 areas were selected to provide multiple candidate areas within four general categories—industrial with combined sewer overflows (CSOs), industrial with no or minimal CSO input, non-industrial with CSOs, and non-industrial with no or minimal CSO input. Table 1 lists the 14 candidate reference areas and the general category they were placed in. The target locations within each candidate reference area are shown on Figures 2 through 15 and are listed in Table 2 of this memorandum. The sampling activities to be completed, which are summarized in this memorandum, will be performed in a manner consistent with the methods outlined in the Remedial Investigation/Feasibility Study Work Plan (RI/FS Work Plan; AECOM 2011) and described in greater detail in the Field Sampling and Analysis Plan (FSAP; Anchor QEA 2011a). -

New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan

NEW YORK CITY CoMPREHENSWE WATERFRONT PLAN Reclaiming the City's Edge For Public Discussion Summer 1992 DAVID N. DINKINS, Mayor City of New lVrk RICHARD L. SCHAFFER, Director Department of City Planning NYC DCP 92-27 NEW YORK CITY COMPREHENSIVE WATERFRONT PLAN CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMA RY 1 INTRODUCTION: SETTING THE COURSE 1 2 PLANNING FRA MEWORK 5 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 5 LEGAL CONTEXT 7 REGULATORY CONTEXT 10 3 THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 17 WATERFRONT RESOURCES AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE 17 Wetlands 18 Significant Coastal Habitats 21 Beaches and Coastal Erosion Areas 22 Water Quality 26 THE PLAN FOR THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 33 Citywide Strategy 33 Special Natural Waterfront Areas 35 4 THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 51 THE EXISTING PUBLIC WATERFRONT 52 THE ACCESSIBLE WATERFRONT: ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES 63 THE PLAN FOR THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 70 Regulatory Strategy 70 Public Access Opportunities 71 5 THE WORKING WATERFRONT 83 HISTORY 83 THE WORKING WATERFRONT TODAY 85 WORKING WATERFRONT ISSUES 101 THE PLAN FOR THE WORKING WATERFRONT 106 Designation Significant Maritime and Industrial Areas 107 JFK and LaGuardia Airport Areas 114 Citywide Strategy fo r the Wo rking Waterfront 115 6 THE REDEVELOPING WATER FRONT 119 THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT TODAY 119 THE IMPORTANCE OF REDEVELOPMENT 122 WATERFRONT DEVELOPMENT ISSUES 125 REDEVELOPMENT CRITERIA 127 THE PLAN FOR THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT 128 7 WATER FRONT ZONING PROPOSAL 145 WATERFRONT AREA 146 ZONING LOTS 147 CALCULATING FLOOR AREA ON WATERFRONTAGE loTS 148 DEFINITION OF WATER DEPENDENT & WATERFRONT ENHANCING USES -

RESTORATION on the EDGE: Exploring the Frontiers of Restoration, Collaboration, and Resilience in Changing Ecosystems

The SER Mid-Atlantic Chapter, together with the SER New England Chapter, presents RESTORATION ON THE EDGE: Exploring the Frontiers of Restoration, Collaboration, and Resilience in Changing Ecosystems Thursday, March 22 – Saturday, March 24, 2012 Brooklyn College Student Center THREE-DAY OVERVIEW (Details on following pages) THURSDAY, MARCH 22 – Pre-Conference Workshop 8:30 am - 5:00 pm (Additional fee; limit 35 attendees) NOAA Restoration Planning Framework FRIDAY, MARCH 23 – Main Conference Day 8:00 am - 6:00 pm Conference Sessions and Poster Pub SATURDAY, MARCH 24 – Field Trips 9:30 am - 3:30 pm (Additional fee; choose one trip) NYC Triple Treat The Bronx River Staten Island Bluebelt Brooklyn Urban Oases (Check www.ser.org/midatl for updates) This year’s conference is jointly supported by Brooklyn College (CUNY) and NYC Parks & Recreation. THURSDAY, MARCH 22, 2012 8:30 am - 5:00 pm NOAA Restoration Planning Framework Pre-Conference Workshop Note: Space in workshop is limited to 35 participants, on a first-come first-served basis. See registration form for fee, which includes continental breakfast and lunch. Workshop to be held in Brooklyn College Student Center. Have you ever implemented a restoration project that didn’t quite meet its intended outcomes? (Be honest!) This interactive, full-day workshop offers restoration practitioners valuable knowledge, skills, and tools to design targeted projects with successful outcomes. Participants will gain insight into restoration project design using a “logic model”-based framework. Interactive exercises will enable participants to build a logic model, create measurable objectives, performance indicators, and outcomes for their own restoration projects. -

NYC Park Crime Stats

1st QTRPARK CRIME REPORT SEVEN MAJOR COMPLAINTS Report covering the period Between Jan 1, 2018 and Mar 31, 2018 GRAND LARCENY OF PARK BOROUGH SIZE (ACRES) CATEGORY Murder RAPE ROBBERY FELONY ASSAULT BURGLARY GRAND LARCENY TOTAL MOTOR VEHICLE PELHAM BAY PARK BRONX 2771.75 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 VAN CORTLANDT PARK BRONX 1146.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 ROCKAWAY BEACH AND BOARDWALK QUEENS 1072.56 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 FRESHKILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 913.32 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK QUEENS 897.69 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01002 03 LATOURETTE PARK & GOLF COURSE STATEN ISLAND 843.97 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 MARINE PARK BROOKLYN 798.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BELT PARKWAY/SHORE PARKWAY BROOKLYN/QUEENS 760.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BRONX PARK BRONX 718.37 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT BOARDWALK AND BEACH STATEN ISLAND 644.35 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 ALLEY POND PARK QUEENS 635.51 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 PROSPECT PARK BROOKLYN 526.25 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 04000 04 FOREST PARK QUEENS 506.86 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GRAND CENTRAL PARKWAY QUEENS 460.16 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FERRY POINT PARK BRONX 413.80 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CONEY ISLAND BEACH & BOARDWALK BROOKLYN 399.20 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 CUNNINGHAM PARK QUEENS 358.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 RICHMOND PARKWAY STATEN ISLAND 350.98 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CROSS ISLAND PARKWAY QUEENS 326.90 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GREAT KILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 315.09 ONE ACRE -

In New York City

Outdoors Outdoors THE FREE NEWSPAPER OF OUTDOOR ADVENTURE JULY / AUGUST / SEPTEMBER 2009 iinn NNewew YYorkork CCityity Includes CALENDAR OF URBAN PARK RANGER FREE PROGRAMS © 2009 Chinyera Johnson | Illustration 2 CITY OF NEW YORK PARKS & RECREATION www.nyc.gov/parks/rangers URBAN PARK RANGERS Message from: Don Riepe, Jamaica Bay Guardian To counteract this problem, the American Littoral Society in partnership with NYC Department of Parks & Recreation, National Park Service, NYC Department of Environmental Protection, NY State Department of Environmental Conservation, Jamaica Bay EcoWatchers, NYC Audubon Society, NYC Sierra Club and many other groups are working on various projects designed to remove debris and help restore the bay. This spring, we’ve organized a restoration cleanup and marsh planting at Plum Beach, a section of Gateway National Recreation Area and a major spawning beach for the ancient horseshoe crab. In May and June during the high tides, the crabs come ashore to lay their eggs as they’ve done for millions of years. This provides a critical food source for the many species of shorebirds that are migrating through New York City. Small fi sh such as mummichogs and killifi sh join in the feast as well. JAMAICA BAY RESTORATION PROJECTS: Since 1986, the Littoral Society has been organizing annual PROTECTING OUR MARINE LIFE shoreline cleanups to document debris and create a greater public awareness of the issue. This September, we’ll conduct Home to many species of fi sh & wildlife, Jamaica Bay has been many cleanups around the bay as part of the annual International degraded over the past 100 years through dredging and fi lling, Coastal Cleanup. -

Gowanus Canal & Newtown Creek Superfund Sites: a Proposal

Gowanus Canal & Newtown Creek Superfund Sites: A Proposal by Larry Schnapf he federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2010 designated as fed eral superfund sites the entire length of T the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn and 3.8 miles of Newtown Creek on the border of Queens and Brooklyn. Property owners near these water bodies fear that EPA's action will lower property values and make it even more difficult to obtain loans and other wise develop their land. Many small businesses also fear that they may become responsible for paying a portion of the cleanup costs. The superfund process could take five to ten years to complete, during which time property owners will be faced with significant economic uncertainty. There is, however, a way tore lieve many of the smaller property owners by giving them an early release. Gowanus Canal Superfund Site The Gowanus Canal (Canal) runs for 1.8 miles through the Brooklyn residential neighborhoods of Gowanus, Park Slope, Cobble Hill, Carroll Gardens, TABLE CJF' CONTENTS and Red Hook. The adjacent waterfront is primarily commercial and industrial, currently consisting of Legislative Update ....................... 75 concrete plants, warehouses, and parking lots. At one CityRegs Update......................... 75 time Brooklyn Union Gas, the predecessor of National Decisions of Interest Grid, operated a large manufactured gas facility on Housing ............................ 76 the shores of the Canal. Affirmative Litigation ................. 77 EPA's initial investigation identified a variety of Human Rights ....................... 77 contaminants in the Canal's sediments including poly Health .............................. 79 cyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), volatile organ Audits & Reports ..................... 79 ic contaminants (VOCs), polychlorinated biphenyls Land Use ...........................