Draft 2- -2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix B: Fiscal Year 2015-2020 RTAP and RFAP Grant Awards

7. References Photo: Dan Davis Photography Appendix B: Fiscal Year 2015-2020 RTAP and RFAP Grant Awards This page left blank intentionally FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 12, 2016 Thirty-one Rail Projects to Create, Retain 48,000 Jobs with State Investments Harrisburg, PA – More than 48,000 jobs will be created or retained over the next five years due to thirty-one rail projects being made possible by two PennDOT-managed grant programs. “Pennsylvania has the most railroads in the country and these make up a vital component of our economic and transportation activities,” said PennDOT Secretary Leslie S. Richards. “These investments underscore our role in supporting jobs and economies across the state.” The State Transportation Commission (STC) voted today to approve $36 million for 15 projects through the Rail Transportation Assistance Program (RTAP) and 16 projects through the Rail Freight Assistance Program (RFAP). RTAP is a capital budget grant program funded with bonds and RFAP is underwritten through the new Multimodal Fund, created by Act 89. Act 89 is a far-reaching transportation program that clears the way for significant investments in all transportation modes. For more information on rail in Pennsylvania visit www.penndot.gov. Follow PennDOT on Twitter at www.twitter.com/penndotnews, on Instagram at www.instagram.com/pennsylvaniadot, and “like” the department on Facebook at www.facebook.com/pennsylvaniadepartmentoftransportation. MEDIA CONTACT: Rich Kirkpatrick or Erin Waters-Trasatt, 717-783-8800 Editor’s Note: Following is a by-county list of approved rail freight projects under the programs with the state share: RTAP Projects: Allegheny County: CSX Transportation Inc.-- $3 million to construct new main lead track, crossovers, turnouts, and derails to allow intermodal trains to pull off the McKees Rocks mainline to serve the Pittsburgh Intermodal Terminal. -

Total Employment by State, Class of Employer and Last Railroad Employer Calendar Year 2014

Statistical Notes | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | U.S. Railroad Retirement Board Bureau of the Actuary www.rrb.gov No. 3 - 2016 May 2016 Total Employment by State, Class of Employer and Last Railroad Employer Calendar Year 2014 The attached table shows total employment by State, class of employer and last railroad employer in the year. Total employment includes all employees covered by the Railroad Retirement and Railroad Unemployment Insurance Acts who worked at least one day during calendar year 2014. For employees shown under Unknown for State, either no address is on file (0.7 percent of all employees) or the employee has a foreign address such as Canada (0.2 percent). TOTAL EMPLOYMENT BY STATE, CLASS OF EMPLOYER AND LAST RAILROAD EMPLOYER CALENDAR YEAR 2014 CLASS OF STATE EMPLOYER1 RAILROAD EMPLOYER NUMBER Unknown 1 BNSF RAILWAY COMPANY 4 Unknown 1 CSX TRANSPORTATION INC 2 Unknown 1 DAKOTA MINNESOTA & EASTERN RAILROAD CORPORATION 1 Unknown 1 DELAWARE AND HUDSON RAILWAY COMPANY INC 1 Unknown 1 GRAND TRUNK WESTERN RAILROAD COMPANY 1 Unknown 1 ILLINOIS CENTRAL RR CO 8 Unknown 1 NATIONAL RAILROAD PASSENGER CORP (AMTRAK) 375 Unknown 1 NORFOLK SOUTHERN CORPORATION 9 Unknown 1 SOO LINE RAILROAD COMPANY 2 Unknown 1 UNION PACIFIC RAILROAD COMPANY 3 Unknown 1 WISCONSIN CENTRAL TRANSPORTATION CORP 1 Unknown 2 CANADIAN PACIFIC RAILWAY COMPANY 66 Unknown 2 IOWA INTERSTATE RAILROAD LTD 64 Unknown 2 MONTANA RAIL LINK INC 117 Unknown 2 RAPID CITY, PIERRE & EASTERN RAILROAD, INC 21 Unknown 2 -

TYP One Line Listing

Date: 06/01/2012 03:08 PM 2011 - 2022 Twelve Year Program Page 1 of 234 Rpt# TYP210 Cost ($000) Project Route Title/Sponsor Improvement Period Study PE FD UTL ROW CON PRA Total Planning Partner: Adams Mode: Highway County: Adams 880232011-2014 Bond Reserve Reserve Line Item First 1,080 1,080 880232011-2014 Bond Reserve Reserve Line Item Second 1,789 1,789 880232011-2014 Bond Reserve Reserve Line Item Third 1,073 1,073 70188ACTA - Operations Public Transit First 520 520 88019Adams HRST Line Item Reserve Line Item First 2,891 2,891 88086App 916 Reserve Reserve Line Item First 271 271 88086App 916 Reserve Reserve Line Item Second 4,136 4,136 88086App 916 Reserve Reserve Line Item Third 4,375 4,375 77501Brickyard Road Crossing Rail Highway Grade Crossing First 200 200 87792Bridge Reserve Reserve Line Item First 8,074 8,074 87792Bridge Reserve Reserve Line Item Second 4,147 4,147 87792Bridge Reserve Reserve Line Item Third 19,283 19,283 92377Center Square Master Plan PA Community Transportation Initiative First 75 75 87794CMAQ Line Item Reserve Line Item First 2,526 2,526 87794CMAQ Line Item Reserve Line Item Second 4,251 4,251 87794CMAQ Line Item Reserve Line Item Third 4,994 4,994 87807Delivery / Consult Assist Reserve Line Item First 420 280 700 92301Dist AWPM SFY 2010-2011 Safety Improvement First 356 356 87809ENH Line Item Reserve Line Item First 286 286 87809ENH Line Item Reserve Line Item Second 911 911 87809ENH Line Item Reserve Line Item Third 1,066 1,066 90071Gettysbrg/Hbg Express Svc Congestion Reduction First 264 264 87793Highway -

FY 2015-2020 RTAP and RFAP Grant Awards

7. References Photo: Dan Davis Photography Appendix B: Fiscal Year 2015-2020 RTAP and RFAP Grant Awards This page left blank intentionally FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 12, 2016 Thirty-one Rail Projects to Create, Retain 48,000 Jobs with State Investments Harrisburg, PA – More than 48,000 jobs will be created or retained over the next five years due to thirty-one rail projects being made possible by two PennDOT-managed grant programs. “Pennsylvania has the most railroads in the country and these make up a vital component of our economic and transportation activities,” said PennDOT Secretary Leslie S. Richards. “These investments underscore our role in supporting jobs and economies across the state.” The State Transportation Commission (STC) voted today to approve $36 million for 15 projects through the Rail Transportation Assistance Program (RTAP) and 16 projects through the Rail Freight Assistance Program (RFAP). RTAP is a capital budget grant program funded with bonds and RFAP is underwritten through the new Multimodal Fund, created by Act 89. Act 89 is a far-reaching transportation program that clears the way for significant investments in all transportation modes. For more information on rail in Pennsylvania visit www.penndot.gov. Follow PennDOT on Twitter at www.twitter.com/penndotnews, on Instagram at www.instagram.com/pennsylvaniadot, and “like” the department on Facebook at www.facebook.com/pennsylvaniadepartmentoftransportation. MEDIA CONTACT: Rich Kirkpatrick or Erin Waters-Trasatt, 717-783-8800 Editor’s Note: Following is a by-county list of approved rail freight projects under the programs with the state share: RTAP Projects: Allegheny County: CSX Transportation Inc.-- $3 million to construct new main lead track, crossovers, turnouts, and derails to allow intermodal trains to pull off the McKees Rocks mainline to serve the Pittsburgh Intermodal Terminal. -

Class I Railroad Annual Report

OEEAA – R1 OMB Clearance No. 2140-0009 Expiration Date 12-31-2022 Class I Railroad Annual Report Norfolk Southern Combined Railroad Subsidiaries Three Commercial Place Norfolk, VA 23510-2191 Full name and address of reporting carrier Correct name and address if different than shown (Use mailing label on original, copy in full on duplicate) To the Surface Transportation Board For the Year Ending December 31, 2020 Road Initials: NS Rail Year: 2020 ANNUAL REPORT OF NORFOLK SOUTHERN COMBINED RAILROAD SUBSIDIARIES ("NS RAIL") TO THE SURFACE TRANSPORTATION BOARD FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 Name, official title, telephone number, and office address of officer in charge of correspondence with the Board regarding this report. (Name) Clyde H. "Jake" Allison Jr. (Title) Vice President and Controller (Telephone number) (757) 629-2680 (Area code) (Telephone number) (Office address) Three Commercial Place Norfolk, Virginia 23510-2191 (Street and number, city, state, and ZIP code) Railroad Annual Report R-1 NOTICE 1. This report is required for every class I railroad operating within the United States. Three copies of this Annual Report should be completed. Two of the copies must be filed with the Surface Transportation Board, Office of Economics, Environmental Analysis, and Administration, 395 E Street, S.W. Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20423, by March 31 of the year following that for which the report is made. One copy should be retained by the carrier. 2. Every inquiry must be definitely answered. Where the word "none" truly and completely states the fact, it should be given as the answer. If any inquiry is inapplicable, the words "not applicable" should be used. -

2018 STB R-1 Report

OEEAA – R1 OMB Clearance No. 2140-0009 Expiration Date 12-31-2019 Class I Railroad Annual Report Norfolk Southern Combined Railroad Subsidiaries Three Commercial Place Norfolk, VA 23510-2191 Full name and address of reporting carrier Correct name and address if different than shown (Use mailing label on original, copy in full on duplicate) To the Surface Transportation Board For the Year Ending December 31, 2018 NOTICE 1. This report is required for every class I railroad operating within the United States. Three copies of this Annual Report should be completed. Two of the copies must be filed with the Surface Transportation Board, Office of Economics, Environmental Analysis, and Administration, 395 E Street, S.W. Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20423, by March 31 of the year following that for which the report is made. One copy should be retained by the carrier. 2. Every inquiry must be definitely answered. Where the word "none" truly and completely states the fact, it should be given as the answer. If any inquiry is inapplicable, the words "not applicable" should be used. 3. Wherever the space provided in the schedules in insufficient to permit a full and complete statement of the requested information, inserts should be prepared and appropriately identified by the number of the schedule. 4. All entries should be made in a permanent black ink or typed. Those of a contrary character must be indicated in parenthesis. Items of an unusual character must be indicated by appropriate symbols and explained in footnotes. 5. Money items, except averages, throughout the annual report form should be shown in thousands of dollars adjusted to accord with footings. -

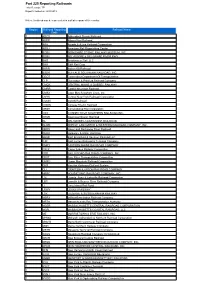

Part 225 Reporting Railroads.Pdf

Part 225 Reporting Railroads Total Records: 771 Report Created on: 4/30/2019 Notes: A railroad may be represented in multiple regions of the country. Region Railroad Reporting Railroad Name Code 1 ADCX Adirondack Scenic Railroad 1 APRR Albany Port Railroad 1 ARA Arcade & Attica Railroad Corporation 1 ARDJ American Rail Dispatching Center 1 BCRY BERKSHIRE SCENIC RAILWAY MUSEUM, INC. 1 BDRV BELVEDERE & DELAWARE RIVER RWY 1 BHR Brookhaven Rail, LLC 1 BHX B&H Rail Corp 1 BKRR Batten Kill Railroad 1 BSOR BUFFALO SOUTHERN RAILROAD, INC. 1 CDOT Connecticut Department Of Transportation 1 CLP Clarendon & Pittsford Railroad Company 1 CMQX CENTRAL MAINE & QUEBEC RAILWAY 1 CMRR Catskill Mountain Railroad 1 CMSX Cape May Seashore Lines, Inc. 1 CNYK Central New York Railroad Corporation 1 COGN COGN Railroad 1 CONW Conway Scenic Railroad 1 CRSH Consolidated Rail Corporation 1 CSO CONNECTICUT SOUTHERN RAILROAD INC. 1 DESR Downeast Scenic Railroad 1 DL DELAWARE LACKAWANNA RAILROAD 1 DLWR DEPEW, LANCASTER & WESTERN RAILROAD COMPANY, INC. 1 DRRV Dover and Rockaway River Railroad 1 DURR Delaware & Ulster Rail Ride 1 EBSR East Brookfield & Spencer Railroad LLC 1 EJR East Jersey Railroad & Terminal Company 1 EMRY EASTERN MAINE RAILROAD COMPANY 1 FGLK Finger Lakes Railway Corporation 1 FRR FALLS ROAD RAILROAD COMPANY, INC. 1 FRVT Fore River Transportation Corporation 1 GMRC Green Mountain Railroad Corporation 1 GRS Pan Am Railways/Guilford System 1 GU GRAFTON & UPTON RAILROAD COMPANY 1 HRRC HOUSATONIC RAILROAD COMPANY, INC. 1 LAL Livonia, Avon & Lakeville Railroad Corporation 1 LBR Lowville & Beaver River Railroad Company 1 LI Long Island Rail Road 1 LRWY LEHIGH RAILWAY 1 LSX LUZERNE & SUSQUEHANNA RAILWAY 1 MBRX Milford-Bennington Railroad Company 1 MBTA Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority 1 MCER MASSACHUSETTS CENTRAL RAILROAD CORPORATION 1 MCRL MASSACHUSETTS COASTAL RAILROAD, LLC 1 ME MORRISTOWN & ERIE RAILWAY, INC. -

Total Employment by State, Class of Employer and Last Railroad Employer Calendar Year 2012

Statistical Notes | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | U.S. Railroad Retirement Board Bureau of the Actuary www.rrb.gov No. 2 - 2014 May 2014 Total Employment by State, Class of Employer and Last Railroad Employer Calendar Year 2012 The attached table shows total employment by State, class of employer and last railroad employer in the year. Total employment includes all employees covered by the Railroad Retirement and Railroad Unemployment Insurance Acts who worked at least one day during calendar year 2012. For employees shown under Unknown for State, either no address is on file (1.1 percent of all employees) or the employee has a foreign address such as Canada (0.3 percent). TOTAL EMPLOYMENT BY STATE, CLASS OF EMPLOYER AND LAST RAILROAD EMPLOYER CALENDAR YEAR 2012 CLASS OF STATE EMPLOYER1 RAILROAD EMPLOYER NUMBER Unknown 1 CSX TRANSPORTATION INC 15 Unknown 1 ILLINOIS CENTRAL RR CO 333 Unknown 1 NATIONAL RAILROAD PASSENGER CORP (AMTRAK) 709 Unknown 1 NORFOLK SOUTHERN CORPORATION 18 Unknown 1 SOO LINE RAILROAD COMPANY 2 Unknown 1 UNION PACIFIC RAILROAD COMPANY 3 Unknown 2 CANADIAN PACIFIC RAILWAY COMPANY 188 Unknown 2 FLORIDA EAST COAST RAILWAY, LLC 65 Unknown 2 IOWA INTERSTATE RAILROAD LTD 32 Unknown 2 PADUCAH & LOUISVILLE RAILWAY INC 17 Unknown 2 SPRINGFIELD TERMINAL RY CO VERMONT 131 Unknown 2 WISCONSIN & SOUTHERN RAILROAD, LLC 48 Unknown 3 A&R TERMINAL RAILROAD, LLC 1 Unknown 3 ALABAMA & TENNESSEE RIVER RAILWAY, LLC 10 Unknown 3 ALLEGHENY VALLEY RAILROAD COMPANY 2 Unknown 3 ALLIANCE -

Growing the Business Short Lines July/Aug ’12

Volume 4, Issue 4 | July-August 2012 Growing the business Growing Short lines July/Aug ’12 SHORT LINES 1 EXTEND NS’ REACH 6 HELPING NS TAP A MAJOR GAS PLAY 8 PROVIDING OPTIONS TO NS’ AG MARKETS 9 FLEXIBILITY FOR NS’ AUTO BUSINESS R3 INITIATIVE 10 POSITIONS NS FOR GROWTH GATHERING OF NS’ 13 HERITAGE FLEET: A PICTURE-PERFECT OPPORTUNITY RAISING THE BAR 21 ON STOP SIGNAL SAFETY MAKING EVERY 24 MOVE COUNT WHEN SAFETY 26 ON THE JOB HITS HOME NS 27 HEROES NS CARRIES ITS From moving grain and automobiles to hauling materials used to mine the gas-rich 28 OWN OLYMPICS Marcellus Shale deposit, Norfolk Southern’s network of short line rail partners has TORCH – FOR helped the company expand some of its most dynamic commodity markets. DIVERSITY In 2011, NS set records with its short line business. For the year, some 250 short FROM THE NS lines hauled nearly 1.1 million carloads of freight for NS that collectively represented 29 ARCHIVES 23 percent of the company’s railway operating revenues. The performance surpassed pre-recession highs for revenue in 2008 and carloads in 2006. BACK EMPLOYEES COVER HELP SUSTAIN COMMUNITIES 2 BizNS July / Aug 2012 extend NS’ reach Those impressive numbers reflect the strategic approach by NS’ n ABOVE: Norfolk Southern partners with the short line marketing group to grow traffic and extend NS’ reach into Commonwealth Railway to move international local markets. freight to and from the Virginia state port terminal “At the end of the day, it’s about business growth and about in Portsmouth, Va., a facility CR serves directly. -

Draft PA State Rail Plan

This page left blank intentionally Draft 2020 Pennsylvania State Rail Plan [contact information] [All copyright-protected information and images in this document used with permission or a license.] [auspices] [copyright] This page left blank intentionally Executive Summary The 2020 Pennsylvania State Rail Plan includes a comprehensive description and assessment of the current rail system, an analysis of the role of rail and integration within the state’s transportation system, and a vision for the future of passenger and freight rail in the commonwealth. A Rail Service and Investment Program (RSIP) is included to provide guidelines and identify rail investments needed to achieve Pennsylvania’s vision for the rail system in the short (2021–2024) and long range (2025–2045). This State Rail Plan meets the requirements stated in the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) State Rail Plan Guidance issued in September 2013, Section 303 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (PRIIA) (P. L. No. 110-432), and Section 11315 of the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act of 2015 (FAST Act) (P. L. No. 114-94). State Rail Vision The 2020 State Rail Vision was developed through a collaborative effort and is intended to provide the framework for passenger and freight rail improvement projects. 2020 State Rail Vision Pennsylvania’s integrated rail system will provide safe, convenient, reliable, cost-effective connections for people and goods. As a viable alternative to other modes, it will support economic competitiveness, smart growth, environmental sustainability, and resiliency, thereby strengthening Pennsylvania’s communities. To achieve this vision, several goals and supporting objectives have been identified. -

FEDERAL REGISTER INDEX January–November 2020

FEDERAL REGISTER INDEX January–November 2020 Surface Transportation Board Patton-Lowe RR, Inc.; Consolidated Rail Corp. – 409 ( Jan 3) RULES TFG Transport, LLC; Decatur Central Railroad, LLC – 39968 ( Jul 2) Civil Monetary Penalties-2020 Adjustment – 838 ( Jan 8) Acquisition of Control Exemption: Jon Delli Priscoli and First Colony Development and Rail Holdings Co.; Demurrage Billing Requirements – 26858 ( May 6) Massachusetts Coastal Railroad, LLC – 36930 ( Jun 18) Exclusion of Demurrage Regulation from Certain Class Exemptions – 12749 Acquisition of Control: ( Mar 4) Winthrop Sargent, John Cogliano, and Paul Fuerst; Plymouth and Brockton Market Dominance Streamlined Approach – 47675 ( Aug 6) Street Railway Co., Brush Hill Transportation Co., and McGinn Bus Co., Petition for Rulemaking; Railroad Performance Data Reporting – 30849 Inc. – 410 ( Jan 3) ( May 21) Agency Information Collection Activities; Proposals, Submissions, and Policy Statement on Demurrage and Accessorial Rules and Approvals – 64215 ( Oct 9) Charges – 26866 ( May 6) Agency Information Collection Activities; Proposals, Submissions, and Policy Statement on Factors Considered in Assessing Civil Monetary Approvals: Penalties on Small Entities – 41422 ( Jul 10) Arbitration Opt-In Notices – 11440 ( Feb 27) Regulations Governing Fees for Services Performed in Connection with Complaints – 31020 ( May 21); 42481 ( Jul 14) Licensing and Related Services; 2020 Update – 47099 ( Aug 4) Dispute Resolution Procedures under the Fixing America's Surface Waybill Sample Reporting – 54936 -

2015 Rail Freight Assistance Program

August 2016 2015 RAIL FREIGHT ASSISTANCE PROGRAM Total Project State County Applicant Project Name Project Description Cost Share Projects Recommended for Funding Alumax Mill Construct 1,500 foot double rail LANCASTER Double Rail Spur $357,143 $250,000 Products, Inc. spur including two new switches. Consolidated Rail Conrail Marcus Hook Replace three existing railroad DELAWARE $371,069 $259,748 Corporation Diamond Rehab diamonds. Repair the Delaware Lackawanna railroad bridge over the West The Delaware- Branch Lehigh River. Repairs LACKAWANNA, Lackawanna\ Bridge MP 113.52 include wingwall and backwall $987,000 $690,900 WAYNE Railroad Company Rehabilitation restoration, bridge seat cleaning, Inc. face resurfacing, and re- establishment of original bridge elevation. BERKS, ESPN Track Rehab - Rehabilitate the Lancaster East Penn Railroad LANCASTER, Lancaster Northern & Northern and York Line, including $800,000 $560,000 LLC YORK York Lines tie replacement and surfacing. Replace 4,000 linear feet of rail, The Everett Everett Railroad Track 1,200 ties, one public grade BLAIR $514,500 $360,150 Railroad Company Improvement crossing, and surface two miles of track. JMC Steel Group Construct two industrial spur Wheatland Tube MERCER dba Wheatland tracks, two turnouts, and a loading/ $375,000 $262,500 Industrial Spur Tracks Tube Company unloading pad. Kane Warehousing Warehouse DC5 Rail Construct 1,000 track foot spur LACKAWANNA $325,000 $227,500 Inc. Expansion and one No. 8 turnout. Leetsdale Industrial Leetsdale Industrial Construct two new spurs, and ALLEGHENY $428,374 $299,862 Corporation Park raise, line, and surface track. Install a runaround track at ROCK BRADFORD, Lehigh Railway ROCK Siding and Rail station and install five rail flange $418,162 $292,713 WYOMING LLC Lubricators lubricators along Lehigh Railway's main line.