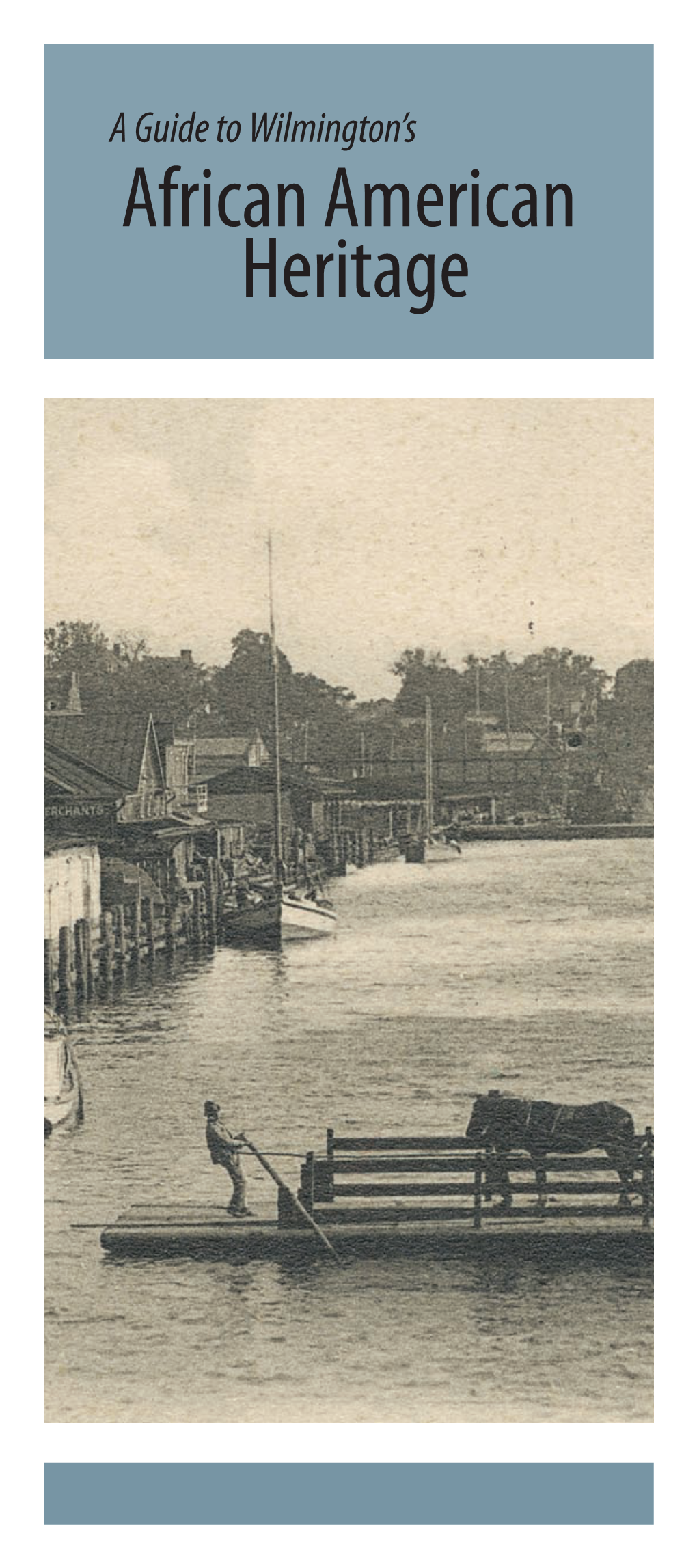

African American Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE OUTSIDER ART FAIR ANNOUNCES EXHIBITORS & PROGRAMMING for the 26TH EDITION of the NEW YORK FAIR January

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE OUTSIDER ART FAIR ANNOUNCES EXHIBITORS & PROGRAMMING FOR THE 26TH EDITION OF THE NEW YORK FAIR January 18 – January 21, 2018 The Metropolitan Pavilion, 125 West 18th Street, New York Bill Traylor, untitled (detail), 1939-1942, charcoal on cardboard, 14" x 8", collection Audrey Heckler, photo by Adam Reich NEW YORK, NY – Wide Open Arts, the New York-based organizer of the Outsider Art Fair – the premier event championing self-taught art, art brut and outsider art – is excited to announce its exhibitors for the 26th edition, taking place January 18-21, 2018 at The Metropolitan Pavilion. The fair will showcase 63 galleries, representing 35 cities from 7 countries, with 10 first-time exhibitors. Coming off of a successful 5th edition of Outsider Art Fair Paris, which posted a 24% gain in attendance over the previous year, the 26th edition of the New York fair will continue to highlight the global reach of its artists and dealers, including: ex-voto sculptures unique to Brazil’s Afro-Indigenous-European culture at Mariposa Unusual Art; and a collection of works by self-taught artists from Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean at Indigo Arts. Korea Art Brut and Beijing’s Almost Art Project will make their OAF debuts, as will Antillean, who will present work by three Jamaican artists, each of whom use found materials to evoke shanty village life. Drawings by New Zealand’s Susan Te Kahurangi King will be the subject of a solo presentation at Chris Byrne and the sensational ceramic sculptures of Shinichi Sawada will be shown in New York for the first time at Jennifer Lauren Gallery. -

Accidental Genius

Accidental Genius Accidental Genius ART FROM THE ANTHONY PETULLO COLLECTION Margaret Andera Lisa Stone with an introduction by Jane Kallir Milwaukee Art Museum DelMonico Books Prestel MUNICH LONDON NEW YORK CONTENTS 19 FOREWORD Daniel T. Keegan 21 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Margaret Andera 23 Art Brut and “Outsider” Art A Changing Landscape Jane Kallir 29 “It’s a picture already” The Anthony Petullo Collection Lisa Stone 45 PLATES 177 THE ANTHONY PETULLO COLLECTION 199 BIOGRAPHIES OF THE ARTISTS !" FOREWORD Daniel T. KeeganDirector, Milwaukee Art Museum The Milwaukee Art Museum is pleased to present Accidental Genius: the Roger Brown Study Collection at the School of the Art Institute Art from the Anthony Petullo Collection, an exhibition that celebrates of Chicago, for her insightful essay for this publication. the gift to the Museum of Anthony Petullo’s collection of modern A project of this magnitude would not have been possible self-taught art. Comprising more than three hundred artworks, the without generous financial support. The Milwaukee Art Museum collection is the most extensive grouping of its kind in any American wishes to thank the Anthony Petullo Foundation; Leslie Hindman, museum or in private hands. Thanks to this gift, the Milwaukee Art Inc.; the Einhorn Family Foundation; and Friends of Art, a support Museum’s holdings now encompass a broadly inclusive represen- group of the Museum, for sponsoring the exhibition. Tony Petullo tation of self-taught art as an international phenomenon. is a past president of Friends of Art, and he credits the group for Tony Petullo, a retired Milwaukee businessman, built his col- introducing him to collecting. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE OUTSIDER ART FAIR ANNOUNCES EXHIBITORS for ITS 27TH NEW YORK EDITION January 17 – January 20, 2019 the M

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE OUTSIDER ART FAIR ANNOUNCES EXHIBITORS FOR ITS 27TH NEW YORK EDITION January 17 – January 20, 2019 The Metropolitan Pavilion, 125 West 18th Street, New York Minnie Evans, Untitled (Three faces in floral design) (detail),1967, Crayon, graphite and oil on canvas board, 22.75×27.75 in. Artwork (c) Estate off Minnie Evans. Courtesy of Cameron Art Museum, Wilmington, N.C. NEW YORK, NY, November 28, 2018 – The Outsider Art Fair, the only fair dedicated to Self-Taught Art, Art Brut and Outsider Art, is pleased to announce the exhibitor list for its 27th New York edition, taking place January 17-20, 2019 at The Metropolitan Pavilion. The fair will showcase 67 exhibitors, representing 37 cities from 7 countries, with 8 first-time galleries. This year, OAF will host two of its hallmark Curated Spaces. Good Kids: Underground Comics from China will feature zines and original drawings created by Chinese artists. Co-organized by Brett Littman (Director, Noguchi Museum, New York) and Yi Zhou (partner and curator of C5Art Gallery, Beijing), these works deal with subject matter that is scatological, sexual, puerile and anti-conformist, making the distribution and sales of these work in mainland China complicated to almost impossible. A second Curated Space will serve as homage to the late dealer Phyllis Kind. In her obituary for the New York Times, Roberta Smith made this observation: “As the first American dealer to show outsider art alongside that of contemporary artists, Ms. Kind was in many ways as important as Leo Castelli…” Curated by Raw Vision Magazine senior editor and art critic Edward M. -

Historic House Museums

HISTORIC HOUSE MUSEUMS Alabama • Arlington Antebellum Home & Gardens (Birmingham; www.birminghamal.gov/arlington/index.htm) • Bellingrath Gardens and Home (Theodore; www.bellingrath.org) • Gaineswood (Gaineswood; www.preserveala.org/gaineswood.aspx?sm=g_i) • Oakleigh Historic Complex (Mobile; http://hmps.publishpath.com) • Sturdivant Hall (Selma; https://sturdivanthall.com) Alaska • House of Wickersham House (Fairbanks; http://dnr.alaska.gov/parks/units/wickrshm.htm) • Oscar Anderson House Museum (Anchorage; www.anchorage.net/museums-culture-heritage-centers/oscar-anderson-house-museum) Arizona • Douglas Family House Museum (Jerome; http://azstateparks.com/parks/jero/index.html) • Muheim Heritage House Museum (Bisbee; www.bisbeemuseum.org/bmmuheim.html) • Rosson House Museum (Phoenix; www.rossonhousemuseum.org/visit/the-rosson-house) • Sanguinetti House Museum (Yuma; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/museums/welcome-to-sanguinetti-house-museum-yuma/) • Sharlot Hall Museum (Prescott; www.sharlot.org) • Sosa-Carrillo-Fremont House Museum (Tucson; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/welcome-to-the-arizona-history-museum-tucson) • Taliesin West (Scottsdale; www.franklloydwright.org/about/taliesinwesttours.html) Arkansas • Allen House (Monticello; http://allenhousetours.com) • Clayton House (Fort Smith; www.claytonhouse.org) • Historic Arkansas Museum - Conway House, Hinderliter House, Noland House, and Woodruff House (Little Rock; www.historicarkansas.org) • McCollum-Chidester House (Camden; www.ouachitacountyhistoricalsociety.org) • Miss Laura’s -

View Exhibition Brochure

1 Renée Cox (Jamaica, 1960; lives & works in New York) “Redcoat,” from Queen Nanny of the Maroons series, 2004 Color digital inket print on watercolor paper, AP 1, 76 x 44 in. (193 x 111.8 cm) Courtesy of the artist Caribbean: Crossroads of the World, organized This exhibition is organized into six themes by El Museo del Barrio in collaboration with the that consider the objects from various cultural, Queens Museum of Art and The Studio Museum in geographic, historical and visual standpoints: Harlem, explores the complexity of the Caribbean Shades of History, Land of the Outlaw, Patriot region, from the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) to Acts, Counterpoints, Kingdoms of this World and the present. The culmination of nearly a decade Fluid Motions. of collaborative research and scholarship, this exhibition gathers objects that highlight more than At The Studio Museum in Harlem, Shades of two hundred years of history, art and visual culture History explores how artists have perceived from the Caribbean basin and its diaspora. the significance of race and its relevance to the social development, history and culture of the Caribbean: Crossroads engages the rich history of Caribbean, beginning with the pivotal Haitian the Caribbean and its transatlantic cultures. The Revolution. Land of the Outlaw features works broad range of themes examined in this multi- of art that examine dual perceptions of the venue project draws attention to diverse views Caribbean—as both a utopic place of pleasure and of the contemporary Caribbean, and sheds new a land of lawlessness—and investigate historical light on the encounters and exchanges among and contemporary interpretations of the “outlaw.” the countries and territories comprising the New World. -

Visual Art As a Window for Studying the Caribbean Compiled and Introduced by Peter B

Visual Art as a Window for Studying the Caribbean Compiled and introduced by Peter B. Jordens Curaçao: August 26, 2012 The present document is a compilation of 20 reviews and 36 images1 of the visual-art exhiBition Caribbean: Crossroads of the World that is Being held Between June 12, 2012 and January 6, 2013 at three cooperating museums in New York City, USA. The remarkaBle fact that Crossroads has (to date) merited no fewer than 20 fairly formal art reviews in various US newspapers and on art weBlogs can Be explained By the terms of praise in which the reviews descriBe the exhiBition: “likely the most expansive art event of the summer (p. 20 of this compilation), the summer’s BlockBuster exhiBition (p. 21), the big art event of the summer in New York (p. 15), immense (p. 34), Big, varied (p. 21), diverse (p. 10), comprehensive (p. 20), amBitious (pp. 19, 21, 22, 33, 34), impressive (p. 21), remarkaBle (p. 21), not one to miss (p. 30), wholly different and very rewarding (p. 33), satisfying (pp. 21, 33), visual feast (p. 25), Bonanza (p. 25), rare triumph (p. 21), significant (p. 13), unprecedented (p. 10), groundbreaking (pp. 13, 23), a game changer (p. 13), a landmark exhiBition (p. 13), will define all other suBsequent CariBBean surveys for years to come (p. 22).” Crossroads is the most recent tangiBle expression of an increase in interest in and recognition of CariBBean art in the CariBBean diaspora, in particular the USA and to less extent Western Europe. This increase is likely the confluence of such factors as: (1) the consolidation of CariBBean immigrant communities in North America and Europe, (2) the creative originality of artists of CariBBean heritage, (3) these artists’ greater moBility and presence in the diaspora in the context of gloBalization, especially transnational migration, travel and information flows,2 and (4) the politics of multiculturalism and of postcolonial studies. -

Convention District Guide

CONVENTION DISTRICT GUIDE See where the water takes you. 505 Nutt Street, Unit A, Wilmington, NC 28401 | NCCoastalMeetings.com | 800.650.9064 505 Nutt Street, Unit A, Wilmington, NC 28401 | NCCoastalMeetings.com | 800.650.9064 Official publication of the Wilmington and Beaches Convention & Visitors Bureau Official publication of the Wilmington and Beaches Convention & Visitors Bureau INSPIRING MEETINGS START WITH INSPIRING SETTINGS With an award-winning, bustling riverfront, National Register Historic District and nearby island beaches, people are naturally drawn to Wilmington, N.C. Our mild climate and rich culture – including more than 200 restaurants, shops and attractions in the downtown area alone – offer something for everyone. Whether it’s just for a meeting or event, or staying for a few days before or after, Wilmington is the kind of destination planners seek out for their meetings and events. Specializing in small-and medium-size meetings, we offer a multitude of indoor and outdoor meeting and convention facilities and natural settings, as well as an exceptional range of attractions, personalized and professional service, and all the right elements for increasing your meeting attendance at this favorite meeting and vacation destination. CONVENTION DISTRICT CONNECTED BY A SCENIC RIVERWALK Wilmington is one of N.C.’s favorite is the largest convention center on vacation destinations and a natural N.C.’s coast. Located downtown, to become your next favorite it offers sweeping riverfront meetings destination. views and plenty of natural light that helps bring the outdoors in. Our multiuse Convention District Adjacent to the convention center is located riverfront and within is the Port City Marina and Pier Wilmington’s downtown River 33. -

The Enslaved Workers of the Bellamy Site

Wilmington, North Carolina The original slave quarters building, though now rare, was typical of urban slave quarters through- out the United States. A two-story brick building that is one room deep was common, but most slave quarters buildings were converted for other uses after the Civil War or let fall into disrepair and eventuallydemolished. The original slave quarters building at the Bellamy site underwent a complete restoration which was completed in 2014. The photograph above shows the building before the restoration process began. “Sarah...our own old cook...had been left here in charge of the premises.” For more than 70 years, most of what was known about the enslaved men, women, and children who lived and labored on the Bellamy’s Wilmington compound prior to the American Civil War came from Back With the Tide, the memoirs of Ellen D. Bellamy. She included the names and partial job descriptions of some, in quotes like the one above. When they fled the city in 1862, the Bellamys left as caretaker of their townhome Sarah, their enslaved cook and housekeeper. Recent research efforts by Bellamy Museum staff have revealed biographical information about several This publication was made possible of these enslaved workers who were previously only known by a first name in Ellen’s book. While there by a grant from the Women’s Impact is still much to uncover about Sarah, Joan, and Caroline, the lives of Rosella, Mary Ann, Guy and Tony are Network of New Hanover County. the enslaved now better understood. Their biographical sketches are included here. -

Summer 2014 Summer 2014 Number 146 75 Years of Published by Preservation North Carolina, Est

summer 2014 summer 2014 Number 146 75 Years of Published by Preservation North Carolina, Est. 1939 www.PreservationNC.org Preservation reservation North Carolina dates back to 1939, when the North The Historic Preservation Regional Offices and Staff Foundation of North Carolina, Inc. Carolina Society for the Preservation of Antiquities was formed. Headquarters Piedmont Regional Office 2014 Board of Directors 220 Fayetteville Street 735 Ninth Street Its original vision was to encourage the reconstruction of Tryon Suite 200 Suite 56 P.O. Box 27644 P.O. Box 3597 P Eddie Belk, Durham, Chairman Palace in New Bern, the royal governor’s residence that also served as Rodney Swink, Raleigh, Vice Raleigh, NC 27611-7644 Durham, NC 27702-3597 Chairman and Chairman-Elect 919-832-3652 919-401-8540 North Carolina’s colonial capitol. When the Antiquities Society was Bettie Edwards Murchison, Fax 919-832-1651 Fax 919-832-1651 Wake Forest, Secretary e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] founded, Tryon Palace was an archaeological site buried deep under a Fred Belledin, Raleigh, Treasurer Myrick Howard, President Cathleen Turner, Director Diane Althouse, Charlotte, At-Large Robert Parrott, Headquarters US highway, so the plan to reconstruct it was gutsy. Executive Committee Member Regional Director Western Regional Office Jo Ramsay Leimenstoll, Greensboro, Shannon Phillips, Director of 2 1/2 E. Warren Street, Immediate Past Chairman Resource Development Suite 8 Oliver Robinson, Office Shelby, NC 28151-0002 The Antiquities Society stuck with its across the state. This first-in-the-nation Summer Steverson Alston, Durham Assistant 704-482-3531 vision and by the late 1950s succeeded statewide fund focused primarily on James Andrus, Enfield Lauren Werner, Director of Fax 919-832-1651 Millie Barbee, West Jefferson Outreach Education/ e-mail: in getting Tryon Palace rebuilt and open rural and small-town houses that were Ramona Bartos, Raleigh Website Editor [email protected] to the public. -

Art Book Layout 1

The North Carolina State Bar Art Collection The North Carolina State Bar Art Collection Table of Contents Introduction...................................2 Henry, J.M. ...........................................40 Peiser, Mark .........................................86 Herrick, Rachel.....................................42 Powers, Sarah ......................................88 A Special Note of Gratitude ...........3 Hewitt, Mark........................................44 Saltzman, Marvin.................................90 Howell, Claude.....................................46 Sayre, Thomas......................................92 Irwin, Robert........................................48 Stevens, William Henry .......................94 Artists Jackson, Herb.......................................50 Tustin, Gayle.........................................96 Bearden, Romare...................................4 Johnson, Robert...................................52 Ulinski, Anthony...................................98 Beecham, Gary ......................................6 Johnston, Daniel ..................................54 Vogel, Kate (John Littleton)..................62 Bireline, George .....................................8 Kinnaird, Richard..................................56 White, Edwin .....................................100 Bradford, Elizabeth ..............................10 Kircher, Mary........................................58 Womble, Jimmy Craig II.....................102 Bromberg, Tina ....................................12 Link, Henry...........................................60 -

Winter 2014-15 Winter 2014-15 Number 148 This Year, Our 75Th Anniversary, Has Been Incredibly Busy for Published by Preservation North Carolina, Est

winter 2014-15 winter 2014-15 Number 148 This year, our 75th Anniversary, has been incredibly busy for Published by Preservation North Carolina, Est. 1939 Preservation North Carolina (PNC). www.PreservationNC.org The Historic Preservation Regional Offices and Staff e had a wild ride during the summer as the general assembly Foundation of North Carolina, Inc. Headquarters Northeast Regional Office considered the renewal of the state’s rehabilitation tax 2014 Board of Directors 220 Fayetteville Street 117 E. King Street Suite 200 Edenton, NC 27932 Rodney Swink, Raleigh, Chairman P.O. Box 27644 252-482-7455 credits program. In its final hours, the legislature failed to Fred Belledin, Raleigh, Vice Chairman Raleigh, NC 27611-7644 Fax 919-832-1651 W and Chairman-elect 919-832-3652 e-mail: extend them. Though historic preservation received unprecedented Bettie Edwards Murchison, Fax 919-832-1651 [email protected] Wake Forest, Secretary e-mail: [email protected] local political and media support, it wasn’t enough to overcome Don Tise, Chapel Hill, Treasurer Claudia Deviney, Director Bruce Hazzard, Asheville, At-Large Myrick Howard, President objections rooted in tax reform. Some key legislative opponents have Executive Committee Member Elizabeth Marsh, Office Piedmont Regional Office Eddie Belk, Durham, Immediate Past Assistant 735 Ninth Street, expressed their willingness to work out a solution in 2015. Chairman Robert Parrott, Regional Suite 56 Director P.O. Box 3597 Diane Althouse, Charlotte Shannon Phillips, Director of Durham, NC 27702-3597 -

DESCENDANTS of JOHN VAUGHT

DESCENDANTS of JOHN VAUGHT Last Updated 11 July 2003 Please forward questions and comments to Sam Pait at the address shown above. This web site supports research, represents sharing of the work of several people, and may contain errors and omissions. Please help by offering corrections and additions. Descendants of John Vaught, Sr. Generation No. 1 1. John1 Vaught, Sr. was born Abt. 1725 in Hannover, Germany, and died Abt. 1795 in Charleston, South Carolina. He married Unknown. Children of John Vaught and Unknown are: + 2 i. Matthias 2 Vaught, Sr., born May 31, 1750 in At sea between Germany and Charleston, South Carolina; died November 13, 1833 in Charleston, South Carolina. + 3 ii. John Vaught, Jr., born Abt. 1757 in Charleston, South Carolina; died Abt. 1809 in Charleston, South Carolina. Generation No. 2 2. Matthias 2 Vaught, Sr. (John 1 ) was born May 31, 1750 in At sea between Germany and Charleston, South Carolina, and died November 13, 1833 in Charleston, South Carolina. He married Martha Mercy Todd, daughter of Captain Todd and Mrs. Todd. She was born Abt. 1750. Notes for Matthias Vaught, Sr.: Matthias and his wife settled on a plantation between Wampee and Re Bluff near what was later called Hardee's Mill. Children of Matthias Vaught and Martha Todd are: + 4 i. Charlotte 3 Vaught. + 5 ii. Rebecca Vaught. 6 iii. William Vaught. He married Mary Hankins. 7 iv. Mary Vaught, born Abt. 1772 in Horry County, South Carolina. She married Francis D. Price; born in North Carolina. 8 v. Sarah Vaught, born Abt. 1774.