Examining the Portland Music Scene Through Neo-Localism" (2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot |

1/9/2017 Live Review: The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot | www.splicetoday.com EMAIL/USERNAME PASS (FORGOT?) Email Password NEW USER? LOGIN MUSIC DEC 02, 2009, 06:07AM Live Review: The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot Matt Poland [/authors/Matt%20Poland] Straight from the Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro, North Carolina. The following audio was included in this article: The following audio was included in this article: A few years after American indie folk’s middecade spike in visibility, which, with overexposed albums including Devendra Banhart’s Rejoicing in the Hands and Joanna Newsom’s Ys, may not have been a musical zenith, the http://www.splicetoday.com/music/live-review-the-low-anthem-and-blind-pilot 1/6 1/9/2017 Live Review: The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot | www.splicetoday.com genre has settled back into an unassuming position that seems to fit the music better. The “freak folk” fringe having largely faded, the nourishing, elemental influence of Americana in all its permutations continues to generate quietly exciting new music. This was evident last week at Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro, North Carolina, during an evening of itinerant, wornin, unbeaten songs performed by The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot. Both bands make music that is melancholy but not maudlin, that is steeped in oldtime American music but not anachronistic. The Low Anthem, a Rhode Island trio, began their set with pretty unconventional instrumentation: Ben Knox Miller playing acoustic guitar and singing, Jeffrey Prystowsky on organ, and Jocie Adams playing the crotales— sort of a small xylophone made up of discs instead of planks—with a violin bow, by far the most interesting thing I’ve seen done with a violin bow since I last saw Sigur Rós. -

Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics

1A VOLUME 30 NUMBER 5 JUNE 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL 365 Manual Application of Controlled Forces to Thoracic and Lumbar Spine With a Device: Rated Comfort for the 333 Outcome Research Receiver’s Back and the Applier’s Hands Nikolai Bogduk, MD, PhD, DSc Gordon Waddington, PhD, Gordon Lau, BAppSc (Physiotherapy) (Hons), and Roger Adams, PhD JMPT 335 Highlights 374 Effect of Age and Sex on Heart Rate Variability in Healthy Subjects ORIGINAL ARTICLES John Zhang, MD, PhD 336 Preliminary Morphological Evidence That Vertebral 380 A Single-Blind Pilot Study to Determine Risk and Hypomobility Induces Synaptic Plasticity in the Spinal Cord Association Between Navicular Drop, Calcaneal Barclay W. Bakkum, DC, PhD, Charles N.R. Henderson, Eversion, and Low Back Pain DC, PhD, Se-Pyo Hong, DC, PhD, and Gregory D. Cramer, James W. Brantingham, DC, PhD, Katy Jane Adams, DC, PhD MSc Chiropractic, Jeffery R. Cooley, DC, Denise Globe, DC, MS, PhD, and Gary Globe, DC, MBA, PhD 343 Neck Muscle Endurance in Nonspecific Patients With 386 Interexaminer Reliability and Accuracy of Posterior Neck Pain and in Patients After Anterior Cervical Superior Iliac Spine and Iliac Crest Palpation for Spinal Decompression and Fusion Level Estimations Anneli Peolsson, PhD, PT, and Görel Kjellman, PhD, PT Hye Won Kim, MD, PhD, Young Jin Ko, MD, PhD, Won Ihl Rhee, MD, PhD, Jung Soo Lee, MD, 351 Cerebrospinal Fluid Pressure in the Anesthetized Rat Ji Eun Lim, MD, Sang Jee Lee, MD, Sun Im, MD, Brian S. Budgell, PhD, and Philip S. Bolton, PhD and Jong In Lee, MD, PhD LITERATURE REVIEW 357 Muscular and Postural Demands of Using a Massage Chair and Massage Table 390 Coupling Behavior of the Thoracic Spine: A Systematic Fearon A. -

RAR Newsletter 110914.Indd

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 9/14/2011 Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds “If I Had A Gun” The first US single from their self titled album, in stores 11/8 and going for official AAA adds on Monday On PlayMPE now Added early: KCSN, WYEP, WNRN, WEXT, WFIV, KCLC, WBJB, WAPS, KDEC and building quickly at Modern Rock Appearing on Letterman 11/10 - network TV debut! Catch their North American tour dates in November Julian Velard “Love Again For The First Time” Going for official adds now! Mr. Saturday Night full cd on your desk, single on the latest Taste Of Triple A Added early at KBAC Catch his US tour dates with Sharon Little in October and November - see page 2 “A sunshine-filled collection of daytime radio-friendly classic pop... twelve timeless treats!” - New! Matthew Sweet Blind Pilot “She Walks The Night” “We Are The Tide” New: WNKU, WMNF, WCBE, KUT In stores 9/27 The title track from their new album, going for adds now Early: WCNR, WEHM, KBAC, KCSN, WBJB, KDHX, New: KSMT, DMX Adult Alt, WFIV, KLCC, WFIT... WOCM, WGWG, WHRV Full cd on your desk now ON: KEXP, KBAC, WYCE, KHUM, WNRN, KDHX, See him on tour in October and November KTBG, WCBE, KXCI, KRCL, MPR... In stores now! celebrating the 20th anniversary of his Girlfriend album “We Are The Tide is a treasure of a record... its woozy indie-pop is vibrant and “Sounds like a classic sunny Sweet power pop tune.” - Rolling Stone intoxicating.” - Denver Post Extensive national tour Debut album sold over 50K Mike Doughty “Na Na Nothing” The Duke & The King “Shaky” BDS Indicator 11*! New: KUT, WEHM, KCLC, WDIY, KLCC In stores now From the self titled album featuring Simon Felice of The Felice Brothers ON: WXRV, WXPK, KPND, KCMP, WFUV, WYEP, WCNR, WERS, XM Loft, WDST.. -

Right Arm Resource Update

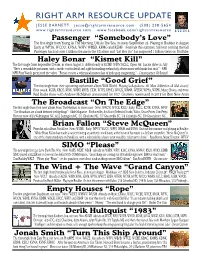

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 6/22/2016 Passenger “Somebody’s Love” The first single from Young As The Morning, Old As The Sea, in stores September 23 Playing in Boulder in August Early at WPYA, WCOO, KVNA, WFIV, WBSD, KFMG and KSMF Festivals this summer, full tour coming this fall Passenger has had over 1 billion streams in the US alone and “Let Her Go” has surpassed 1 billion views on YouTube Haley Bonar “Kismet Kill” The first single from Impossible Dream, in stores August 5 Added early at KCMP, WFIV, KCLC, Open Air Lucius dates in July “She’s a remarkable performer, with a terrific ear for detail and a gift for masking melancholy observations with hooks that stick.” - NPR NPR First Watch premiered the video “Bonar creates a whimsical masterclass of indie-pop songwriting.” - Consequence Of Sound Bastille “Good Grief” The first single from their upcoming sophomore album Wild World Playing Lollapalooza #1 Most Added on all AAA charts! First week: KGSR, KBCO, KINK, WXRV, KRVB, CIDR, WTTS, KPND, WNCS, WRNR, WZEW, WPYA, WXPK, Music Choice and more Red Rocks show with Andrew McMahon announced for 10/7 Grammy nominated in 2015 for Best New Artist The Broadcast “On The Edge” The first single from their new album From The Horizon, in stores now New: WNCW, WYCE, KSLU Early: KCLC, KDTR, KVNA, WFIV “The Broadcast are a band destined for big things” - Glide Magazine Produced by Jim Scott (Tedeschi Trucks, Wilco, Grace Potter, Tom Petty) On tour now: 6/23 Wilmington NC, 6/25 Lexington NC, 7/1 Charlotte NC, 7/7 Greenville SC, 7/8 Columbia SC, 7/9 Greensboro NC.. -

Lobero LIVE Presents Blind Pilot with Special Guest Andrew Duhon Tuesday, February 11 at 8 PM

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Angie Bertucci | 805.679.6010 | [email protected] Tickets: Lobero Box Office | 805.963.0761 | Lobero.com Hi-resolution photos available at lobero.org/press Lobero LIVE presents Blind Pilot with special guest Andrew Duhon Tuesday, February 11 at 8 PM Santa Barbara, CA, January 16, 2020 – Lobero LIVE welcomes Blind Pilot and special guest Andrew Duhon for a special evening on Tuesday, February 11 at 8 PM. Blind Pilot, which consists of Israel Nebeker, Ryan Dobrowski, Kati Claborn, Dave Jorgensen, Ian Krist and Luke Ydstie, was formed in Portland, Oregon in 2007 when songwriter Israel Nebeker and co-founding member Ryan Dobrowski went on a west coast tour via bicycle. Twelve years later, Blind Pilot has released three studio albums, 3 Rounds And A Sound (2008), We Are The Tide (2011) and And Then Like Lions (2016) and has sold out concerts throughout the U.S., Europe and the UK since its inception. The band has performed on “Ellen” and “The Late Show With David Letterman,” as well as at Newport Folk Festival, Bonnaroo, and Lollapalooza among others. Israel Nebeker’s intricate songs have made a meaningful connection to a worldwide audience. His strong lyricism and colorful melodies have anchored the critically-acclaimed band and their albums, in addition to numerous pop/folk tribute compilations to artists including John Denver, Jackson Browne, and a recent collaboration with Don Henley. “The Portland, Ore., band makes wistful late-summer music — songs of reflection and connection, carried out in a subtle swirl of strings, horns, pianos and voices.” – NPR New Orleans native Andrew Duhon, is a writer with an undeniable voice, weighted and soulful. -

Industry Newsletter

On The Radio December 2, 2011 December 23, 2011 Brett Dennen, The Kruger Brothers, (Rebroadcast from March 25, 2011) Red Clay Ramblers, Charlie Worsham, Nikki Lane Cake, The Old 97’s, Hayes Carll, Hot Club of Cowtown December 9, 2011 Dawes, James McMurtry, Blitzen Trapper, December 30, 2011 Jason Isbell & The 400 Unit, Matthew Sweet (Rebroadcast from April 1, 2011) Mavis Staples, Dougie MacLean, Joy Kills Sorrow, December 16, 2011 Mollie O’Brien & Rich Moore, Tim O’Brien The Nighthawks, Chanler Travis Three-O, Milk Carton Kids, Sarah Siskind, Lucy Wainwright Roche Hayes Carll James McMurtry Mountain Stage® from NPR is a production of West Virginia Public Broadcasting December 2011 On The Radio December 2, 2011 December 9, 2011 Nikki Lane Stage Notes Stage Notes Brett Dennen - In the early 2000s, Northern California native Brett Dennen Dawes – The California-based roots rocking Dawes consists of brothers Tay- was a camp counselor who played guitar, wrote songs and performed fireside. lor and Griffin Goldsmith, Wylie Weber and Tay Strathairn. Formed in the Los With a self-made album, he began playing coffee shops along the West Coast Angeles suburb of North Hills, this young group quickly became a favorite of and picked up a devoted following. Dennen has toured with John Mayer, the critics, fans and the veteran musicians who influenced its music. After connect- John Butler Trio, Rodrigo y Gabriela and Ben Folds. On 2007’s “Hope For the ing with producer Jonathan Wilson, the group began informal jam sessions Hopeless,” he was joined by Femi Kuti, Natalie Merchant, and Jason Mraz. -

BIO It Was on September 23, 2008 That Blitzen Trapper, After Putting Out

BLITZEN TRAPPER: BIO It was on September 23, 2008 that Blitzen Trapper, after putting out three albums on its own label, released its fourth full-length album, Furr, via Sub Pop. At that time, it was a record that captured exactly where the band’s frontman, Eric Earley, found himself, both literally and metaphorically, geographically and existentially. Not that the Portland-based musician actually remembers much about the creation of the record’s 13 intriguing, spellbinding songs. Or, more specifically, what its songs actually mean, either now or then. Instead, Furr, stands as a kind of tribute and elegy to the city that inspired it, but that, a decade later, no longer exists. “What I was trying to do with those recordings,” explains Earley, “was capture this kind of atmosphere that I was feeling and which pervaded the city at that time. I think I was attempting to capture what Portland was at the time and what it felt like to me. That city is gone now. Old Portland, we call it, but Old Portland has disappeared. But this record gives me the feeling of those times and this city— when it was poor and dumpy and really drug-addled. And it also captures the magic of the outlying rural areas that has slowly changed as well.” That magic can be heard in each of these songs, and while the city may have vanished from sight – replaced by a newer, richer, shinier and bigger version of itself – its elegance and fractured beauty is preserved within the bones of this record. -

WOW HALL NOTES G VOL

K k JANUARY 2014 KWOW HALL NOTES g VOL. 26 #1 H WOWHALL.ORGk cohesion comes from the brothers wields a powerful voice that can having spent the last two years on both stir and soothe, whether she the road with new full-time mem- is singing traditional gospel, blues ber Jano Rix, a drummer and ace- standards or her own heartfelt in-the-hole multi-instrumentalist, compositions. A gifted musician whereas they relied on session on both mandolin and drums, and musician-friends to fill out previ- a founding member of the roots ous albums. Jano’s additional band Ollabelle (with whom she harmonies give credence to the old has recorded three CDs), Helm has trope that while two family mem- also performed live with scores of bers often harmonize preternatu- notable musicians like Warren rally, it takes a third, non-related Haynes, The Wood Brothers, and singer for the sound to really shine. Donald Fagen, and her distinctive The Muse marks another mile- voice can be heard on recordings stone for The Wood Brothers: it’s by artists ranging from Mercury the first full-length they’ve record- Rev to Marc Cohn. ed at Southern Ground Studios in Amy’s lengthy resume is high- Nashville. The choice of location lighted by many years of singing was practical, given Nashville’s and playing alongside her father, rich history and network of musi- with whom she conceived, cians, but also symbolic: The launched and perfected the Mid- Wood Brothers are now officially a night Rambles -- intimate perfor- Nashville-based band, with Oliver mances held since 2004 at his home having relocated in 2012, and Chris and studio in Woodstock, N.Y. -

1 2 | Lonestarmusic Lonestarmusic | 3

LoneStarMusic | 1 2 | LoneStarMusic LoneStarMusic | 3 inside this issue SHOVELS AND ROPE pg 38 O’ What Two Can Do The triumphant union, joyful noise and crazy good times of Cary Ann Hearst and Michael Trent by Kelly Dearmore FEATUREs 34 Q&A: Paul Thorn — By Lynne Margolis 48 Sunny Sweeney finds the light — By Holly Gleason 52 Lee Ann Womack: When I come around — By Richard Skanse 56 Cory Branan: The wandering musical spirit of Americana’s free-ranging “No-Hit Wonder” — By Adam Daswon 58 Imagine Houston: An excerpt from Reverb, the new novel by Joe Ely Photo courtesy of All Eyes Media 4 | LoneStarMusic LoneStarMusic | 5 after awhile inside this issue Publisher: Zach Jennings Editor: Richard Skanse Notes from the Editor | By Richard Skanse Creative Director/Layout: Melissa Webb Cover Design: Melissa Webb Advertising/Marketing: Kristen Townsend Apart from the opportunity to work with a team of really good people Advertising: Tara Staglik, Erica — especially graphic designer Melissa Webb, who I’d already known and Brown greatly respected for years — one of the things that appealed most to me Artist & Label Relations: Kristen Townsend about joining this magazine five years ago was owner Zach Jennings’ vision that LoneStarMusic could be about more than just Texas music. Even more Contributing Contributing and Writers Photographers than Texas Red Dirt music. We all agreed that we would still focus on songwriters and roots and/or country(ish) music — pretty much anything Richard Skanse John Carrico that could directly or even indirectly fall under the category of “Americana” in Lynne Margolis Lynne Margolis Brian T. -

RONALD F. TUTRONE, JR., MD,FACS,CPI Chesapeake Urology Associates

RONALD F. TUTRONE, JR., M.D.,FACS,CPI Chesapeake Urology Associates/ Partner Chesapeake Urology Research Associates/ Medical Director 6535 North Charles Street, PPN Suite #’s 625 & 650 Towson, MD 21204 6820 Hospital Drive, Suite #210 8322 Bellona Avenue, Suite #’s 202 & 390 Baltimore, MD 21237 Towson, MD 21204 7580 Buckingham Blvd. Suite # 110 21 Crossroads Drive, Suite #’s 220 & 200 Hanover, MD 21076 Owings Mills, MD 21117 2 Park Center Court, Suite #A Owings Mills, MD 21117 PERSONAL Date of Birth: November 27, 1961 Place of Birth: Brooklyn, NY EDUCATION 9/79-5/83 College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, MA B.A. Chemistry 8/83-6/87 UMDNJ-Rutgers Medical Piscataway, NJ Doctor of Medicine GENERAL SURGERY 7/87-6/88 Kings County Hospital/SUNY-Downstate Medical Center Brooklyn, NY Internship 7/88- 6/89 Kings County Hospital/SUNY-Downstate Medical Center Brooklyn, NY Resident in General Surgery UROLOGY RESIDENCY TRAINING Harvard Program in Urology (Longwood Area) 7/89-9/93 Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Beth Israel Hospital, The Children’s Hospital, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, West Roxbury Veteran’s Hospital Boston, MA ñ Resident in Urological Surgery 7/90-6/91 Hartwell Harrison Urologic Research Laboratory Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA ñ Urologic Research Fellow WORK HISTORY 1997- Present Chesapeake Urology Associates, Partner Chesapeake Urology Research Associates, Medical Director 6535 North Charles St Suite 625 PPN Towson, MD 21204 1 1995 - 1997 Siegel & Langer, M.D., P.A. 21 Crossroads Drive Suite 345 Owings Mills, MD 21117 1993 - 1995 The Urology Center Towson, MD 21204 BOARD CERTIFCIATION/ LICENSURE AND GENERAL CERTIFICATION American Board of Urology ñ Certified: March 24, 1995 ñ Re-Certified: November 2003, November 2013 ñ Certificate #11119 CPI- Certified Principal Investigator November 2012 ñ Renewal November 2016 HOSPITAL AFFILIATIONS ñ Greater Baltimore Medical Center ñ St. -

2K Sports Announces In-Game Soundtrack and Music Partnership with Pitchfork Media for Major League Baseball(R) 2K8

2K Sports Announces In-Game Soundtrack and Music Partnership with Pitchfork Media for Major League Baseball(R) 2K8 February 29, 2008 6:01 PM ET Pitchfork Media and 2K Sports join forces to rock stadiums in Major League Baseball 2K8 and at South by Southwest (SXSW 2008) NEW YORK, Feb 29, 2008 (BUSINESS WIRE) -- 2K Sports, the sports publishing label of Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. (NASDAQ: TTWO), announced today a partnership with renowned and influential music outlet Pitchfork Media in support of the highly anticipated title, Major League Baseball 2K8. Pitchfork has made a name for itself since its inception in 1996 as the de facto online source for quality and discerning music reviews and news. The Pitchfork staff also shares passion for the game of baseball and it is the combination of their passion for music and baseball that makes them the perfect partner in constructing a truly epic soundtrack for Major League Baseball 2K8. 2K Sports has invited Pitchfork Media to select half of the music to be featured in Major League Baseball 2K8, guaranteeing that, along with the deepest and most authentic baseball simulation experience available, fans will also be able to enjoy a cutting-edge selection of the hottest music around - including artists such as Modest Mouse, Peter Bjorn & John, The Cure, The Strokes, LCD Soundsystem, and Black Rebel Motorcycle Club. Each artist and song selected for the game by Pitchfork Media will be denoted as a "Pitchfork Pick," and will include additional bio information as well. In the shared spirit of promoting independent artists and music, 2K Sports will join the 3rd Annual Pitchfork/Windish Agency day party at the SXSW 2008 conference in Austin, Texas on Friday, March 14th. -

Presents We Deliver to All of Teton Valley! TITLE SPONSOR

presents WE DELIVER TO ALL OF TETON VALLEY! TITLE SPONSOR Best burgers in Teton Valley! 2 Large patios • 40 beers on draft! Open 7 days a week 11 am to 11 pm Pizza Buffet 11 am to 3 pm 7 days a week Private parties and catering! • 208-354-8829 WE DELIVER TO ALL OF TETON VALLEY! PUBLISHER Valley Citizen News, Inc EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTORS Jeannette Boner Hope Strong DESIGN & LAYOUT Joe Tondro-Smith AD SALES Dawn Banks AD DESIGN table of contents Joe Tondro-Smith Lane Valiante ANDY FRAsco’s UN 2 Please ask for written permission BLITZEN TRAPPER 5 to reproduce any or all of this BLACK JOE LEWIS & THE HONEYBEARS 6 Music on Main Program. MARCH 4TH MARCHING BAND 9 Printed by Falls Printing, LLC THE STONE FOXES 10 Idaho Falls, ID. ROSIE LEDET & THE ZYDECO PLAYBOYS 13 A portion from advertising sales CARRIE RODRIGUEZ 14 benefit Music on Main by supporting YOUNG DUBLINERS 17 the Teton Valley Foundation which THE MAP 18 produces the event. Please thank the MANDATORY AIR WITH THE MILLER SISTERS advertisers in this publication for their 23 generous support. SHOOK TWINS 24 JET BLACK NINJA FUNKGRASS UNIT 27 Valley Citizen News, Inc SCOTT MCDOUGALL 28 65 South Main, Suite 2 ALTA BOYS 30 Driggs, ID 83422 A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT GONE RIGHT 31 208-354-NEWS(6397) RANDOM CANYON GROWLERS 32 Best burgers in Teton Valley! www.valleycitizen.com DINING GUIDE 33 2 Large patios • 40 beers on draft! Copyright ©2012 KEEP THE GOOD TIMes rollin’ 34 Open 7 days a week 11 am to 11 pm BLUEGRASS CAMP ALL-STARS 35 Pizza Buffet 11 am to 3 pm 7 days a week ELK ATTACK 36 Private parties and catering! • 208-354-8829 Andy Frasco's UN June 28, 2012 The inside is yours.