Special Report: the Impact of Diverse Worldviews on Military Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Los Veteranos—Latinos in WWII

Los Veteranos—Latinos in WWII Over 500,000 Latinos (including 350,000 Mexican Americans and 53,000 Puerto Ricans) served in WWII. Exact numbers are difficult because, with the exception of the 65th Infantry Regiment from Puerto Rico, Latinos were not segregated into separate units, as African Americans were. When war was declared on December 8, 1941, thousands of Latinos were among those that rushed to enlist. Latinos served with distinction throughout Europe, in the Pacific Theater, North Africa, the Aleutians and the Mediterranean. Among other honors earned, thirteen Medals of Honor were awarded to Latinos for service during WWII. In the Pacific Theater, the 158th Regimental Combat Team, of which a large percentage was Latino and Native American, fought in New Guinea and the Philippines. They so impressed General MacArthur that he called them “the greatest fighting combat team ever deployed in battle.” Latino soldiers were of particular aid in the defense of the Philippines. Their fluency in Spanish was invaluable when serving with Spanish speaking Filipinos. These same soldiers were part of the infamous “Bataan Death March.” On Saipan, Marine PFC Guy Gabaldon, a Mexican-American from East Los Angeles who had learned Japanese in his ethnically diverse neighborhood, captured 1,500 Japanese soldiers, earning him the nickname, the “Pied Piper of Saipan.” In the European Theater, Latino soldiers from the 36th Infantry Division from Texas were among the first soldiers to land on Italian soil and suffered heavy casualties crossing the Rapido River at Cassino. The 88th Infantry Division (with draftees from Southwestern states) was ranked in the top 10 for combat effectiveness. -

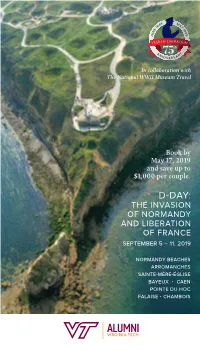

2019 Flagship Vatech Sept5.Indd

In collaboration with The National WWII Museum Travel Book by May 17, 2019 and save up to $1,000 per couple. D-DAY: THE INVASION OF NORMANDY AND LIBERATION OF FRANCE SEPTEMBER 5 – 11, 2019 NORMANDY BEACHES ARROMANCHES SAINTE-MÈRE-ÉGLISE BAYEUX • CAEN POINTE DU HOC FALAISE • CHAMBOIS NORMANDY CHANGES YOU FOREVER Dear Alumni and Friends, Nothing can match learning about the Normandy landings as you visit the ery places where these events unfolded and hear the stories of those who fought there. The story of D-Day and the Allied invasion of Normandy have been at the heart of The National WWII Museum’s mission since they opened their doors as The National D-Day Museum on June 6, 2000, the 56th Anniversary of D-Day. Since then, the Museum in New Orleans has expanded to cover the entire American experience in World War II. The foundation of this institution started with the telling of the American experience on D-Day, and the Normandy travel program is still held in special regard – and is considered to be the very best battlefield tour on the market. Drawing on the historical expertise and extensive archival collection, the Museum’s D-Day tour takes visitors back to June 6, 1944, through a memorable journey from Pegasus Bridge and Sainte-Mère-Église to Omaha Beach and Pointe du Hoc. Along the way, you’ll learn the timeless stories of those who sacrificed everything to pull-off the largest amphibious attack in history, and ultimately secured the freedom we enjoy today. Led by local battlefield guides who are experts in the field, this Normandy travel program offers an exclusive experience that incorporates pieces from the Museum’s oral history and artifact collections into presentations that truly bring history to life. -

Remembering World War Ii in the Late 1990S

REMEMBERING WORLD WAR II IN THE LATE 1990S: A CASE OF PROSTHETIC MEMORY By JONATHAN MONROE BULLINGER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Communication, Information, and Library Studies Written under the direction of Dr. Susan Keith and approved by Dr. Melissa Aronczyk ________________________________________ Dr. Jack Bratich _____________________________________________ Dr. Susan Keith ______________________________________________ Dr. Yael Zerubavel ___________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Remembering World War II in the Late 1990s: A Case of Prosthetic Memory JONATHAN MONROE BULLINGER Dissertation Director: Dr. Susan Keith This dissertation analyzes the late 1990s US remembrance of World War II utilizing Alison Landsberg’s (2004) concept of prosthetic memory. Building upon previous scholarship regarding World War II and memory (Beidler, 1998; Wood, 2006; Bodnar, 2010; Ramsay, 2015), this dissertation analyzes key works including Saving Private Ryan (1998), The Greatest Generation (1998), The Thin Red Line (1998), Medal of Honor (1999), Band of Brothers (2001), Call of Duty (2003), and The Pacific (2010) in order to better understand the version of World War II promulgated by Stephen E. Ambrose, Tom Brokaw, Steven Spielberg, and Tom Hanks. Arguing that this time period and its World War II representations -

The Reel Latina/O Soldier in American War Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 10-26-2012 12:00 AM The Reel Latina/o Soldier in American War Cinema Felipe Q. Quintanilla The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Rafael Montano The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Hispanic Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Felipe Q. Quintanilla 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Quintanilla, Felipe Q., "The Reel Latina/o Soldier in American War Cinema" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 928. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/928 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE REEL LATINA/O SOLDIER IN AMERICAN WAR CINEMA (Thesis format: Monograph) by Felipe Quetzalcoatl Quintanilla Graduate Program in Hispanic Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Hispanic Studies The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Felipe Quetzalcoatl Quintanilla 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ______________________________ -

Military History Digest #336

H-War Military History Digest #336 Blog Post published by David Silbey on Wednesday, April 22, 2020 Ancient: • What Compelled the Roman Way of Warfare? #Reviewing Killing for the Republic https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2020/3/25/-what-compelled-the-roman-way-of-warfar... 18th Century (to 1815): • A Wilderness Adventure: George Washington Comes of Age, Part Ii - Edward Lengel http://www.edwardlengel.com/a-wilderness-adventure-george-washington-comes-of-age-part-ii/ • Clarifying Command | RealClearDefense https://www.realcleardefense.com/2020/04/09/clarifying_command_312941.html • Making & Unmaking a Military Myth: John Adams & the American Riflemen | Beehive http://www.masshist.org/beehiveblog/2020/04/making-unmaking-a-military-myth-john-adams-the... • The Father of My Spirit: Scharnhorst, Clausewitz, and the Value of Mentorship https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2020/4/20/the-father-of-my-spirit-scharnhorst-cla... 1815-1861: • Accidental Guerrilla Syndrome in California, 1836-1846 | Small Wars Journal https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/accidental-guerrilla-syndrome-california-1836-1846 Civil War • John Banks' Civil War Blog: 'Utter Desolation': A Visit to Lee-Grant 'Surrender House' In 1915 https://john-banks.blogspot.com/2020/04/utter-desolation-visit-to-lee-grant.html • Tales From the Army of the Potomac: Liberated by Military Authority: Marylanders in the Army of the Potomac, Part 3. https://talesfromaop.blogspot.com/2020/04/liberated-by-military-authority.html • Tales From the Army of the Potomac: Lt. Col. Durye Will Oust Every One of Us if Possible! Marylanders in the Army of the Potomac, Part 2. http://talesfromaop.blogspot.com/2020/04/lt-col-duryee-will-oust-every-one-of-us.html Citation: David Silbey. -

The Officer at Work: Leadership

CHAPTER FIVE The Officer at Work: Leadership . before it is an honor, leadership is trust; Before it is a call to glory, Leadership is a call to service; . before all else, forever and always, leadership is a willingness to serve. —Father Edson Wood, OSA, Cadet Catholic Chaplain Invocation at Assumption of Command by BG Curtis Scaparrotti, Commandant of Cadets, U.S. Military Academy August 11, 2004 Leadership—convincing others to collaborate effectively in a common endeavor—is the primary function of all Armed Forces officers. Only a few officers are commanders at any particular moment, but every officer is a leader. Indeed the Army and Marine Corps insist that lead- ership is the common responsibility of every Soldier and Marine.1 The Air Force says “Any Airman can be a leader and can positively influ- ence those around him or her to accomplish the mission.”2 A conse- quence is that almost every officer considers himself or herself good at leadership, but perspectives on method differ depending on individual circumstances and experiences. This chapter discusses leadership from four different but overlapping viewpoints: accomplishing the mission and taking care of the troops; three concepts of leadership; Service approaches; and “tribal wisdom,” views of leadership expressed by senior professionals. 57 Accomplishing the Mission and Taking Care of the Troops Leaders are expected to guide their followers to mission success at least possible cost. Lord Moran, who served as a medical officer on the Western Front in World War I, and was Churchill’s doctor and con- fidant in World War II, defined leadership as “the capacity to frame plans which will succeed and the faculty of persuading others to carry them out in the face of death.”3 Moran was skeptical of a requirement for fine character, the honorable virtues, in a leader, but found that a reputation for achieving success was the essential middle term between the ability to formulate a course of action and persuading others to implement it. -

On Sale Through 5/20 $4.95 16 Usa Today Special Edition Remembering D-Day

ON SALE THROUGH 5/20 $4.95 16 USA TODAY SPECIAL EDITION REMEMBERING D-DAY THINGS TO DO 6 ways to mark day Observe D-Day at museums, memorials and the French coast Matt Alderton Special to USA TODAY On June 5, the skies over Normandy, France, will buzz like a hive of angry bees. As the warbling roar grows louder, its source will come into focus as a feet of 38 Douglas C-47 Skytrain transport planes — or “Dakotas,” as they were known in the British Royal Air Force — converge over the village of Ranville to drop some 250 uni- formed paratroopers onto the countryside below. For many in attendance, the event called “Daks Over Normandy” will be like nothing they’ve ever seen. For surviving WWII veterans, however, it will be soberingly familiar, as its reason for being is the 75th anniversary of D-Day — June 6, 1944, when more than 150,000 Allied troops stormed the beaches of Normandy to begin the libera- tion of Western Europe from Nazi tyranny. Preceding the amphibi- ous assault were 24,000 paratroopers who crossed the English Channel in more than 800 Dakotas. It’s their often-unsung contri- bution that Daks Over Normandy will commemorate with the larg- est gathering of Dakotas since the war. “This is probably going to be the last really big D-Day anniversa- ry with living World War II veterans, so we’re doing something ep- ic,” says Moreno “Mo” Aguiari, executive director of the D-Day Squadron, Daks Over Normandy’s American contingent. Daks Over Normandy will be but one in a series of events taking place in Normandy on or around June 6. -

Army Manpower and the War on Terror

Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Working Paper Series Army Manpower and the War on Terror by Kevin Ryan Shorenstein Fellow, Fall 2005 Brigadier General, United States Army (ret.) #2006-2 © 2006 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. Army Manpower and the War on Terror by Kevin T. Ryani Abstract ___________________________________________________________________________ Army manpower is a key factor in the military’s ability to fight the War on Terror, which includes sustaining the combat missions in Iraq and Afghanistan. Yet manpower is a subject that is often misunderstood and misreported. How does the status of Army manpower affect the nation’s War on Terror? What if the manpower demands of concurrent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have sapped the country’s ability to deploy to the next hotspot on the globe? What if recruiting shortfalls leave combat units only half filled? What if frequent deployments for long periods cause professional soldiers to leave the service? And what if the demands of mobilization on the Reserve and Guard mean that those forces are used up and unavailable for a new contingency not yet on the radar? Debating the pros and cons of intervening in Syria, Darfur, and Iran, or even a prolonged presence in Iraq is nothing more than an academic exercise if no troops are available for the operation. This paper provides background material on Army manpower that is meant to inform journalists who might cover the issue. _____________________________________________________________________________ Biographical Note: General Kevin T. Ryan has supervised U.S. government security programs with various foreign militaries and served in Germany, Russia, and Korea. -

The Profession of Arms

An Army White Paper THE PROFESSION OF ARMS I AM AN EXPERT AND I AM A PROFESSIONAL 9TH STANZA SOLDIER’S CREED CG TRADOC Approved 2 December 2010 Authority: This White Paper has been approved for distribution on 2 December 2010 by the Commanding General, Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), under his authority granted by the Secretary of the Army and the Chief of Staff of the Army in the Terms of Reference dated 27 October 2010 for TRADOC to execute the ‗Review of the Army Profession in an Era of Persistent Conflict.‘ Purpose: This White Paper serves to facilitate an Army-wide dialog about our Profession of Arms. It is neither definitive nor authoritative, but a starting point with which to begin discussion. It will be refined throughout calendar year 2010 based on feedback from across our professional community. All members of the profession and those who support the profession are encouraged to engage in this dialog. Distribution: Distribution is unlimited. Yet, the material in this draft is under development. It is NOT approved for reference or citation. Feedback and Participation: Comments on this White Paper should be sent to the Center for the Army Profession and Ethic (CAPE), Combined Arms Center, TRADOC. To get engaged in this review of the Profession of Arms, visit the CAPE website at https://www.us.army.mil/suite/page/611545 and click on the Campaign link. The website will also provide links to professional forums and blogs on the Battle Command Knowledge System to partricipate in this discussion. Authorized for distribution 2 December 2010: Martin E. -

Memory Wars: World War Ii at 75 and Beyond a Conference Exploring World War Ii’S Legacy September 9–11, 2021

MEMORY WARS: WORLD WAR II AT 75 AND BEYOND A CONFERENCE EXPLORING WORLD WAR II’S LEGACY SEPTEMBER 9–11, 2021 PRESENTED BY SPECIAL THANKS TO: LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT American Battle Monuments Commission EA, Respawn Entertainment, and Oculus from Facebook Gallagher & Associates American Historical Association Collegium Civitas Rana Mitter, PhD Dear Friend of The National WWII Museum, John Morrow, PhD 75 years after its official conclusion, World War II is still alive and present Anne Frank House in today’s society. Current news regularly reveals economic, territorial, Mémorial de Caen political or cultural disputes taking place in or among nations, rooted in The Gen. Raymond E. Mason Endowment Fund WWII history. Competing popular and national memories of the war often fuel these conflicts, which sometimes include resurgent forces of racism and extremist ideologies that predated World War II; but dialogue from different perspectives has in many instances also fostered healing. The National WWII Museum will be hosting a first-of-its-kind international conference to address shifting landscapes of popular memories of this world- altering conflict. Memory Wars: World War II at 75 and Beyond will take place September 9–11, 2021, at the new Higgins Hotel & Conference Center. We look forward to bringing together friends, Members, WWII enthusiasts, and students to hear from top scholars, authors, media professionals, and practitioners in the field during three enriching and enjoyable days, discussing one of the most epic events in human history and its remembrance and relevance today. I hope you will consider joining us in New Orleans, as 40 speakers from around the world present ideas from their respective fields and address topics of controversy. -

In the News Vey, in Close Consultation with Schoomaker, Will Also Serve As the Army Lead for All Major Changes to the Program

mond Dubois, and the Army Vice Chief of Staff, General Richard Cody, will oversee this office. Harvey and Schoomaker will conduct an in-depth review of the program a minimum of three times a year. Har- In the News vey, in close consultation with Schoomaker, will also serve as the Army lead for all major changes to the program. ARMY NEWS SERVICE (APRIL 5, 2005) As an additional oversight measure, the Army Audit ARMY ANNOUNCES BUSINESS RESTRUC- Agency, the Army Science Board, and an outside panel TURING OF THE FCS PROGRAM of advisors will conduct periodic independent cost, sched- fter two months of review, Secretary of the Army ule, and technical viability assessments. Dr. Francis J. Harvey today announced a re- Astructuring of the business aspects of the Future AMERICAN FORCES PRESS SERVICE Combat Systems program. The changes are compre- (APRIL 25, 2005) hensive and include contractual, programmatic, and ARMY GENERAL: AIR FORCE HELPED managerial improvements. LOGISTICS SUCCESS IN IRAQ Gerry J. Gilmore The improvements will formally link the FCS program ASHINGTON (AFPN)—The U.S. military’s task to the Army Modular Force Initiative through a Future to supply troops serving in Iraq during the Combat Force Strategy that establishes a framework for Wpast year “was one of the most complex and the continuous progression of the current modular force challenging missions in our history,” a senior Army gen- into the future one. The Future Combat Force Strategy eral said April 20. provides for the spiraling of FCS-based technologies into the current modular force; integration of current com- Yet logisticians “proved successful in supporting a force bat lessons in areas of doctrine, organization, equipment, of (about) 165,000 soldiers, airmen, Marines, and civil- and other key elements, and into the force; and even- ians serving in a country the size of California,” Army Lt. -

World War Ii and Us Cinema

ABSTRACT Title of Document: WORLD WAR II AND U.S. CINEMA: RACE, NATION, AND REMEMBRANCE IN POSTWAR FILM, 1945-1978 Robert Keith Chester, Ph.D., 2011 Co-Directed By: Dr. Gary Gerstle, Professor of History, Vanderbilt University Dr. Nancy Struna, Professor of American Studies, University of Maryland, College Park This dissertation interrogates the meanings retrospectively imposed upon World War II in U.S. motion pictures released between 1945 and the mid-1970s. Focusing on combat films and images of veterans in postwar settings, I trace representations of World War II between war‘s end and the War in Vietnam, charting two distinct yet overlapping trajectories pivotal to the construction of U.S. identity in postwar cinema. The first is the connotations attached to U.S. ethnoracial relations – the presence and absence of a multiethnic, sometimes multiracial soldiery set against the hegemony of U.S. whiteness – in depictions of the war and its aftermath. The second is Hollywood‘s representation (and erasure) of the contributions of the wartime Allies and the ways in which such images engaged with and negotiated postwar international relations. Contrary to notions of a ―good war‖ untainted by ambiguity or dissent, I argue that World War II gave rise to a conflicted cluster of postwar meanings. At times, notably in the early postwar period, the war served as a progressive summons to racial reform. At other times, the war was inscribed as a historical moment in which U.S. racism was either nonexistent or was laid permanently to rest. In regard to the Allies, I locate a Hollywood dialectic between internationalist and unilateralist remembrances.