The Peacock Ravana. UNESCO Collection of Representative Works, Indian Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Peacock Cult in Asia

The Peacock Cult in Asia By P. T h a n k a p p a n N a ir Contents Introduction ( 1 ) Origin of the first Peacock (2) Grand Moghul of the Bird Kingdom (3) How did the Peacock get hundred eye-designs (4) Peacock meat~a table delicacy (5) Peacock in Sculptures & Numismatics (6) Peacock’s place in history (7) Peacock in Sanskrit literature (8) Peacock in Aesthetics & Fine Art (9) Peacock’s place in Indian Folklore (10) Peacock worship in India (11) Peacock worship in Persia & other lands Conclusion Introduction Doubts were entertained about India’s wisdom when Peacock was adopted as her National Bird. There is no difference of opinion among scholars that the original habitat of the peacock is India,or more pre cisely Southern India. We have the authority of the Bible* to show that the peacock was one of the Commodities5 that India exported to the Holy Land in ancient times. This splendid bird had reached Athens by 450 B.C. and had been kept in the island of Samos earlier still. The peacock bridged the cultural gap between the Aryans who were * I Kings 10:22 For the king had at sea a navy of Thar,-shish with the navy of Hiram: once in three years came the navy of Thar’-shish bringing gold, and silver,ivory, and apes,and peacocks. II Chronicles 9: 21 For the King’s ships went to Tarshish with the servants of Hu,-ram: every three years once came the ships of Tarshish bringing gold, and silver,ivory,and apes,and peacocks. -

W.B.C.S.(Exe.) Officers of West Bengal Cadre

W.B.C.S.(EXE.) OFFICERS OF WEST BENGAL CADRE Sl Name/Idcode Batch Present Posting Posting Address Mobile/Email No. 1 ARUN KUMAR 1985 COMPULSORY WAITING NABANNA ,SARAT CHATTERJEE 9432877230 SINGH PERSONNEL AND ROAD ,SHIBPUR, (CS1985028 ) ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS & HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 14-01-1962 E-GOVERNANCE DEPTT. 2 SUVENDU GHOSH 1990 ADDITIONAL DIRECTOR B 18/204, A-B CONNECTOR, +918902267252 (CS1990027 ) B.R.A.I.P.R.D. (TRAINING) KALYANI ,NADIA, WEST suvendughoshsiprd Dob- 21-06-1960 BENGAL 741251 ,PHONE:033 2582 @gmail.com 8161 3 NAMITA ROY 1990 JT. SECY & EX. OFFICIO NABANNA ,14TH FLOOR, 325, +919433746563 MALLICK DIRECTOR SARAT CHATTERJEE (CS1990036 ) INFORMATION & CULTURAL ROAD,HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 28-09-1961 AFFAIRS DEPTT. ,PHONE:2214- 5555,2214-3101 4 MD. ABDUL GANI 1991 SPECIAL SECRETARY MAYUKH BHAVAN, 4TH FLOOR, +919836041082 (CS1991051 ) SUNDARBAN AFFAIRS DEPTT. BIDHANNAGAR, mdabdulgani61@gm Dob- 08-02-1961 KOLKATA-700091 ,PHONE: ail.com 033-2337-3544 5 PARTHA SARATHI 1991 ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER COURT BUILDING, MATHER 9434212636 BANERJEE BURDWAN DIVISION DHAR, GHATAKPARA, (CS1991054 ) CHINSURAH TALUK, HOOGHLY, Dob- 12-01-1964 ,WEST BENGAL 712101 ,PHONE: 033 2680 2170 6 ABHIJIT 1991 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR SHILPA BHAWAN,28,3, PODDAR 9874047447 MUKHOPADHYAY WBSIDC COURT, TIRETTI, KOLKATA, ontaranga.abhijit@g (CS1991058 ) WEST BENGAL 700012 mail.com Dob- 24-12-1963 7 SUJAY SARKAR 1991 DIRECTOR (HR) BIDYUT UNNAYAN BHAVAN 9434961715 (CS1991059 ) WBSEDCL ,3/C BLOCK -LA SECTOR III sujay_piyal@rediff Dob- 22-12-1968 ,SALT LAKE CITY KOL-98, PH- mail.com 23591917 8 LALITA 1991 SECRETARY KHADYA BHAWAN COMPLEX 9433273656 AGARWALA WEST BENGAL INFORMATION ,11A, MIRZA GHALIB ST. agarwalalalita@gma (CS1991060 ) COMMISSION JANBAZAR, TALTALA, il.com Dob- 10-10-1967 KOLKATA-700135 9 MD. -

Shri Sai Baba

Sai Mandir USA 1889 Grand Avenue, Baldwin, NY 11510, USA Designed & Developed by : Praveen Batchu http://www.imagicapps.com SHRI SAI SATCHARITA OR THE WONDERFUL LIFE AND TEACHINGS OF SHRI SAI BABA Adapted from the original Marathi book by Hemadpant by Nagesh Vasudev Gunaji, B.A., L.L.B. 227, Thalakwadi, Belgaum. changes to the current version to make a easy reading experience to American devotees. This book is available for free to all devotees. Published by Kashinath Sitaram Pathak, Court Receiver, Shri Sai Baba Sansthan, Shirdi, ‘Sai Niketan’, 804-B, Dr. Ambedkar Road, Dadar, Bombay 400 014. This book will be available for sale at the following places: (1) Court Receiver, Shri Sai Sansthan, Shirdi, P.O. Shirdi, (Dist. Ahmednagar). (2) Shri Kashinath Sitaram Pathak, Court Receiver, Shri Sai Baba Sansthan, Shirdi, “Sai Niketan”, 804-B, Dr. Ambedkar Road, Dadar, Bombay 400 014. Copyright reserved by the Sansthan Printed by N.D. Rege, at Mohan Printery, 425-A Mogul Lane, Mahim, Bombay 400 016 and Published by Shri Kashinath Sitaram Pathak, Court Receiver, Shri Sai Baba Sansthan, Shirdi, “Sai Niketan”, 804-B, Dr. Ambedkar Road, Dadar, Bombay 400 014. DEDICATION “Whosoever offers to me, with love or devotion, a leaf, a flower, a fruit or water, that offering of love of the pure and self-controlled man is willingly and readily accepted by me.” Lord Shri Krishna in Bhagavad Gita, IX - 26 To Shri Sai Baba The Antaryamin This work with myself Editor : Laura Keller New York, USA SHRI SAI SATCHARITA CONTENTS Preface by the author Preface to the second edition Preface by Shri N.A. -

Downloaded License

philological encounters 6 (2021) 15–42 brill.com/phen Vision, Worship, and the Transmutation of the Vedas into Sacred Scripture. The Publication of Bhagavān Vedaḥ in 1970 Borayin Larios | orcid: 0000-0001-7237-9089 Institut für Südasien-, Tibet- und Buddhismuskunde, Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria [email protected] Abstract This article discusses the first Indian compilation of the four Vedic Saṃhitās into a printed book in the year 1971 entitled “Bhagavān Vedaḥ.” This endeavor was the life’s mission of an udāsīn ascetic called Guru Gaṅgeśvarānand Mahārāj (1881–1992) who in the year 1968 founded the “Gaṅgeśvar Caturved Sansthān” in Bombay and appointed one of his main disciples, Svāmī Ānand Bhāskarānand, to oversee the publication of the book. His main motivation was to have a physical representation of the Vedas for Hindus to be able to have the darśana (auspicious sight) of the Vedas and wor- ship them in book form. This contribution explores the institutions and individuals involved in the editorial work and its dissemination, and zooms into the processes that allowed for the transition from orality to print culture, and ultimately what it means when the Vedas are materialized into “the book of the Hindus.” Keywords Vedas – bibliolatry – materiality – modern Hinduism – darśana – holy book … “Hey Amritasya Putra—O sons of the Immortal. Bhagwan Ved has come to give you peace. Bhagwan Ved brings together all Indians and spreads the message of Brotherhood. Gayatri Maata is there in every state of India. This day is indeed very auspicious for India but © Borayin Larios, 2021 | doi:10.1163/24519197-bja10016 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license. -

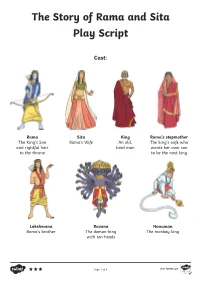

The Story of Rama and Sita Play Script

The Story of Rama and Sita Play Script Cast: Rama Sita King Rama’s stepmother The King’s Son Rama’s Wife An old, The king’s wife who and rightful heir tired man wants her own son to the throne to be the next king Lakshmana Ravana Hanuman Rama’s brother The demon-king The monkey king with ten heads Cast continued: Fawn Monkey Army Narrator 1 Monkey 1 Narrator 2 Monkey 2 Narrator 3 Monkey 3 Narrator 4 Monkey 4 Monkey 5 Prop Ideas: Character Masks Throne Cloak Gold Bracelets Walking Stick Bow and Arrow Diva Lamps (Health and Safety Note-candles should not be used) Audio Ideas: Bird Song Forest Animal Noises Lights up. The palace gardens. Rama and Sita enter the stage. They walk around, talking and laughing as the narrator speaks. Birds can be heard in the background. Once upon a time, there was a great warrior, Prince Rama, who had a beautiful Narrator 1: wife named Sita. Rama and Sita stop walking and stand in the middle of the stage. Sita: (looking up to the sky) What a beautiful day. Rama: (looking at Sita) Nothing compares to your beauty. Sita: (smiling) Come, let’s continue. Rama and Sita continue to walk around the stage, talking and laughing as the narrator continues. Rama was the eldest son of the king. He was a good man and popular with Narrator 1: the people of the land. He would become king one day, however his stepmother wanted her son to inherit the throne instead. Rama’s stepmother enters the stage. -

Sugriva's Role in Ramayana

ROLES IN RAMAYANA HANUMAN’S ROLE IN RAMAYANA Hanuman's role in the battle between Rama and Ravana is huge. He is the one who flies cross the oceans (he is Wind's child), locates the exact place where Sita is imprisoned and brings this information back to Rama. While within the demon fort on his quest for Sita, he sets the entire place on fire and warns Ravana about an impending attack unless Sita is returned unharmed. During the Rama-Ravana battle, Hanuman not only kills several demon generals but also brings Rama's brother back to life. How does he do that? Well, it so happens that Rama's brother is mortally wounded by Ravana's son, and the monkey-army-physician opines that the only things that can save the life of the younger prince are four specific herbs that grow on the Himalayan slopes. The catch? The battle is raging on in Lanka, across the southernmost tip of the country while the Himalayas are far up north, and the herbs are needed within the next few hours, before the new day dawns. Hanuman leaps up into the air, flies northwards at lightning speed, and alights atop the Himalayas. This is where things start to become confusing: the monkey- physician had said that medicine herbs glow in their own light and that it should be easy, therefore, to spot them. What Hanuman sees, however, is an entire mountain aglow with herbs of all kinds, each emitting its own peculiar light. Being unable to identify the exact four herbs that the physician had described, Hanuman uproots the entire mountain and carries it back to the battlefield. -

EUROPEAN BULLETIN of HIMALAYAN RESEARCH EBHR | Issue 54 (2020)

54 Spring 2020 EBHR EUROPEAN BULLETIN OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH EBHR | Issue 54 (2020) The European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR) was founded by the late Richard Burghart in 1991 and has appeared twice yearly ever since. It is the result of a partnership and is edited on a rotating basis between the Centre for Himalayan Studies (CEH: Centre d’études himalayennes) within the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) in France, the South Asia Institute at Heidelberg University in Germany and the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in the United Kingdom. From 2019 to 2023, EBHR is hosted at the Centre for Himalayan Studies. Co-editors Tristan Bruslé (CNRS-CEH), Stéphane Gros (CNRS-CEH), Philippe Ramirez (CNRS-CEH) Associate editor Arik Moran (University of Haifa), book review editor Copyeditor Bernadette Sellers (CNRS-CEH) The following email address should be used for subscription details and any correspondence regarding the journal: [email protected] Back issues of the journal are accessible on the Digital Himalaya platform: http://www.digitalhimalaya.com/ebhr Editorial Board Adhikari, Jagannath (Australian National University) Arora, Vibha (Indian Institute of Technology) Bleie, Tone (University of Tromsø) Campbell, Ben (Durham University) Chhetri, Mona (Australia India Institute) De Maaker, Erik (Leiden University) de Sales, Anne (CNRS-LESC) Dollfus, Pascale (CNRS-CEH) Gaenszle, Martin (University of Vienna) Gellner, David (University of Oxford) Grandin, Ingemar (Linköping University) Hausner, Sondra L. (University -

The Ramayana by R.K. Narayan

Table of Contents About the Author Title Page Copyright Page Introduction Dedication Chapter 1 - RAMA’S INITIATION Chapter 2 - THE WEDDING Chapter 3 - TWO PROMISES REVIVED Chapter 4 - ENCOUNTERS IN EXILE Chapter 5 - THE GRAND TORMENTOR Chapter 6 - VALI Chapter 7 - WHEN THE RAINS CEASE Chapter 8 - MEMENTO FROM RAMA Chapter 9 - RAVANA IN COUNCIL Chapter 10 - ACROSS THE OCEAN Chapter 11 - THE SIEGE OF LANKA Chapter 12 - RAMA AND RAVANA IN BATTLE Chapter 13 - INTERLUDE Chapter 14 - THE CORONATION Epilogue Glossary THE RAMAYANA R. K. NARAYAN was born on October 10, 1906, in Madras, South India, and educated there and at Maharaja’s College in Mysore. His first novel, Swami and Friends (1935), and its successor, The Bachelor of Arts (1937), are both set in the fictional territory of Malgudi, of which John Updike wrote, “Few writers since Dickens can match the effect of colorful teeming that Narayan’s fictional city of Malgudi conveys; its population is as sharply chiseled as a temple frieze, and as endless, with always, one feels, more characters round the corner.” Narayan wrote many more novels set in Malgudi, including The English Teacher (1945), The Financial Expert (1952), and The Guide (1958), which won him the Sahitya Akademi (India’s National Academy of Letters) Award, his country’s highest honor. His collections of short fiction include A Horse and Two Goats, Malgudi Days, and Under the Banyan Tree. Graham Greene, Narayan’s friend and literary champion, said, “He has offered me a second home. Without him I could never have known what it is like to be Indian.” Narayan’s fiction earned him comparisons to the work of writers including Anton Chekhov, William Faulkner, O. -

Ramlila of Ramnagar: an Introduction

Ramlila of Ramnagar: An Introduction Richard Schechner, Texts, Oppositions, and the Ganga River The subject of Ramlila, even Ram nagar Ramlila alone, is vast ... It touches on several texts: Ramayana of Valmiki, never uttered, but present all the same in the very fibre of Rama's story; Tulsidasa's Ramcharitmanas chanted in its entirety from before the start of the performance of Ramlila to its end. I mean that the Ramayanis spend ten days before the first lila up on the covered roof of the small 'tiring house-green room next to the square where on the twenty-ninth day of the performance Bharata Milapa will take place; there on that roof the Ramayanis chant the start of the Ramcharitmanas, from its first word till the granting of Ravana's boon : "Hear me, Lord of the World (Brahma). 1 would die at the hand of none save man or monkey." Shades of Macbeth's meeting with the witches: "For none of woman born shall harm Macbeth." Ravana, like Macbeth, is too proud. Nothing of this until the granting of Ravana's boon is heard by the Maharaja of Benares, or by the faithful daily audience called nemi-s, nor by the hundreds of sadhu-s who stream into Ramnagar for Ramlila summoned by Rama and by the Maharaja's generosity in offering sadhu-s dharamshala-s for rest and rations for the belly. The "sadhu rations" are by far the largest single expense in the Ramnagar Ramlila budget- Rs. 18,000 in 1976. Only the Ramayanis hear the start of the Ramcharitmanas- they and scholars whose job it is to "do and hear and see everything." But this, we soon discovered, is impossible: too many things happen simultaneously, scattered out across Ramnagar. -

Ravana Questions Hanuman

Volume 2009 Issue 31 Article 12 7-15-2009 Ravana Questions Hanuman Randy Hoyt Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mcircle Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hoyt, Randy (2009) "Ravana Questions Hanuman," The Mythic Circle: Vol. 2009 : Iss. 31 , Article 12. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mcircle/vol2009/iss31/12 This Fiction is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Mythic Circle by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm This fiction is available in The Mythic Circle: https://dc.swosu.edu/mcircle/vol2009/iss31/12 own place, and in itself / Can make a heaven listen to this counter-infernal nonsense?” of hell, a hell of heaven’ (1.254-255).” He threw himself upon Astaroth, who ran Squidgeboodle said, “It has been one of toward the door with a shriek. The rest of our notable successes to induce most of the the committee followed, texting bets to each American and European academics to take other on their cell phones. -

My HANUMAN CHALISA My HANUMAN CHALISA

my HANUMAN CHALISA my HANUMAN CHALISA DEVDUTT PATTANAIK Illustrations by the author Published by Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 2017 7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj New Delhi 110002 Copyright © Devdutt Pattanaik 2017 Illustrations Copyright © Devdutt Pattanaik 2017 Cover illustration: Hanuman carrying the mountain bearing the Sanjivani herb while crushing the demon Kalanemi underfoot. The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-81-291-3770-8 First impression 2017 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The moral right of the author has been asserted. This edition is for sale in the Indian Subcontinent only. Design and typeset in Garamond by Special Effects, Mumbai This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. To the trolls, without and within Contents Why My Hanuman Chalisa? The Text The Exploration Doha 1: Establishing the Mind-Temple Doha 2: Statement of Desire Chaupai 1: Why Monkey as God Chaupai 2: Son of Wind Chaupai 3: -

Analysis of Hindu Widowhood in Indian Literature Dipti Mayee Sahoo

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 21, Issue 9, Ver. 7 (Sep. 2016) PP 64-71 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Analysis Of Hindu Widowhood In Indian Literature Dipti Mayee Sahoo Asst. Prof. SociologyTrident Academy of Creative technology,Bhubaneswar Abstract:- In ancient India, women occupied a very important position, in fact a superior position to, men. It is a culture whose only words for strength and power are feminine -"Shakti'' means "power'' and "strength.'' All male power comes from the feminine. Literary evidence suggests that kings and towns were destroyed because a single woman was wronged by the state. For example, Valmiki's Ramayana teaches us that Ravana and his entire clan was wiped out because he abducted Sita. Veda Vyasa'sMahabharatha teaches us that all the Kauravas were killed because they humiliated Draupadi in public. ElangoAdigal'sSillapathigaram teaches us Madurai, the capital of the Pandyas was burnt because PandyanNedunchezhiyan mistakenly killed her husband on theft charges. "In Hinduism, the momentous event of a foundation at one point in time, the initial splash in the water, from which concentric circles expand to cover an ever-wider part of the total surface, is absent. The waves that carried Hinduism to a great many shores are not connected to a central historical fact or to a common historic movement. " Key words:- Feminine, sakti, strength, humiliation, power. I. INTRODUCTION In this age of ascending feminism and focus on equality and human rights, it is difficult to assimilate the Hindu practice of sati, the burning to death of a widow on her husband's funeral pyre, into our modern world.