Symphony Box NOTES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heroes / Low Symphonies Mp3, Flac, Wma

Bowie Heroes / Low Symphonies mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Heroes / Low Symphonies Country: Europe Released: 2003 Style: Contemporary MP3 version RAR size: 1762 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1736 mb WMA version RAR size: 1677 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 492 Other Formats: VQF AUD WAV MP4 FLAC ADX DMF Tracklist Heroes Symphony 1-1 Heroes 5:53 1-2 Abdulmajid 8:53 1-3 Sense Of Doubt 7:21 1-4 Sons Of The Silent Age 8:19 1-5 Neuköln 6:44 1-6 V2 Schneider 6:49 Low Symphony 2-1 Subterraneans 15:11 2-2 Some Are 11:20 2-3 Warszawa 16:01 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Decca Music Group Limited Copyright (c) – Decca Music Group Limited Record Company – Universal Music Phonographic Copyright (p) – Universal International Music B.V. Credits Composed By – Philip Glass Conductor [Associate Conductor] – Michael Riesman (tracks: 1-1 to 1-6) Conductor [Principal] – Dennis Russell Davies Engineer – Dante DeSole (tracks: 2-1 to 2-3), Rich Costey (tracks: 1-1 to 1-6) Executive-Producer – Kurt Munkacsi, Philip Glass, Rory Johnston Music By [From The Music By] – Brian Eno, David Bowie Orchestra – American Composers Orchestra (tracks: 1-1 to 1-6), The Brooklyn Philharmonic Orchestra Producer – Kurt Munkacsi, Michael Riesman Producer [Associate] – Stephan Farber (tracks: 1-1 to 1-6) Notes This compilation ℗ 2003 Decca Music Group Limited © 2003 Decca Music Group Limited CD 1 ℗ 1997 Universal International Music BV CD 2 ℗ 1993 Universal International Music BV Artists listed as: Bowie & Eno meet Glass on spine; Glass Bowie Eno on front cover; Bowie Eno Glass on both discs. -

Masayoshi Sukita “40Th Anniversary of David Bowie's Heroes”

Masayoshi Sukita “40th Anniversary of David Bowie's Heroes” 12. Mai – 12. August 2017 Heroes © 1977 / 1997 Risky Folio, Inc. Courtesy of The David Bowie Archive ™ Preisliste / Pricelist All pictures of the exhibition are titled and signed on the back including local sales tax (19%). galerie hiltawsky Tucholskystraße 41, 10117 Berlin +49 (0)30 285 044 99 | (0)171 81 34 567 Di – Sa 14 – 19 Uhr u.n.V. Masayoshi Sukita 40th Anniversary of David Bowie's Heroes 12. Mai – 12. August 2017 Preisliste / Pricelist 01. Masayoshi Sukita, "Heroes" To Come, Japan, 1977 Lambda print on Fuji photographic paper 50,8 cm x 40,6 cm, Edition 10/30, € 1.950 02. Masayoshi Sukita, MY-MY / MY-MY, Japan, 1977 Lambda print on Fuji photographic paper 40,6 cm x 50,8 cm, Edition 4/30, € 1.950 03. Masayoshi Sukita, 1977 n°1, Japan, 1977 Lambda print on Fuji photographic paper 76,2 cm x 101,6 cm, Edition 1/10, € 3.900 Masayoshi Sukita 40th Anniversary of David Bowie's Heroes 12. Mai – 12. August 2017 Preisliste / Pricelist 04. Masayoshi Sukita, 1977 n°2, Japan, 1977 Lambda print on Fuji photographic paper 40,6 cm x 50,8 cm, Edition 1/30, € 1.950 05. Masayoshi Sukita, "Heroes", Japan, 1977 Lambda print on Fuji photographic paper 40,6 cm x 50,8 cm, Edition 18/30, € 29.000 (one of the last 2 available !) 06. Masayoshi Sukita, 1977 n°3, Japan, 1977 Lambda print on Fuji photographic paper 40,6 cm x 50,8 cm, Edition 1/30, € 1.950 Masayoshi Sukita 40th Anniversary of David Bowie's Heroes 12. -

Prohibition Premieres October 2, 3 & 4

Pl a nnerMichiana’s bi-monthly Guide to WNIT Public Television Issue No. 5 September — October 2011 A FILM BY KEN BURNS AND LYNN NOVICK PROHIBITION PREMIERES OCTOBER 2, 3 & 4 BrainGames continues September 29 and October 20 Board of Directors Mary’s Message Mary Pruess Chairman President and GM, WNIT Public Television Glenn E. Killoren Vice Chairmen David M. Findlay Rodney F. Ganey President Mary Pruess Treasurer Craig D. Sullivan Secretary Ida Reynolds Watson Directors Roger Benko Janet M. Botz WNIT Public Television is at the heart of the Michiana community. We work hard every Kathryn Demarais day to stay connected with the people of our area. One way we do this is to actively engage in Robert G. Douglass Irene E. Eskridge partnerships with businesses, clubs and organizations throughout our region. These groups, David D. Gibson in addition to the hundreds of Michiana businesses that help underwrite our programs, William A. Gitlin provide WNIT with constant and immediate contact to our viewers and to the general Tracy D. Graham Michiana community. Kreg Gruber Larry D. Harding WNIT maintains strong partnerships and active working relationship with, among others, James W. Hillman groups representing the performing arts – Arts Everywhere, Art Beat, the Fischoff National Najeeb A. Khan Chamber Music Association, the Notre Dame Shakespeare Festival, the Krasl Art Center in Evelyn Kirkwood Kevin J. Morrison St. Joseph, the Lubeznik Center for the Arts in Michigan City and the Southwest Michigan John T. Phair Symphony; civic and cultural organizations like the Center for History, Fernwood Botanical Richard J. Rice Garden and Nature Center and the Historic Preservation Commission; educational, social Jill Richardson and healthcare organizations such as WVPE National Public Radio, the St. -

Bob Dylan and the Reimagining of Woody Guthrie (January 1968)

Woody Guthrie Annual, 4 (2018): Carney, “With Electric Breath” “With Electric Breath”: Bob Dylan and the Reimagining of Woody Guthrie (January 1968) Court Carney In 1956, police in New Jersey apprehended Woody Guthrie on the presumption of vagrancy. Then in his mid-40s, Guthrie would spend the next (and last) eleven years of his life in various hospitals: Greystone Park in New Jersey, Brooklyn State Hospital, and, finally, the Creedmoor Psychiatric Center, where he died. Woody suffered since the late 1940s when the symptoms of Huntington’s disease first appeared—symptoms that were often confused with alcoholism or mental instability. As Guthrie disappeared from public view in the late 1950s, 1,300 miles away, Bob Dylan was in Hibbing, Minnesota, learning to play doo-wop and Little Richard covers. 1 Young Dylan was about to have his career path illuminated after attending one of Buddy Holly’s final shows. By the time Dylan reached New York in 1961, heavily under the influence of Woody’s music, Guthrie had been hospitalized for almost five years and with his motor skills greatly deteriorated. This meeting between the still stylistically unformed Dylan and Woody—far removed from his 1940s heyday—had the makings of myth, regardless of the blurred details. Whatever transpired between them, the pilgrimage to Woody transfixed Dylan, and the young Minnesotan would go on to model his early career on the elder songwriter’s legacy. More than any other of Woody’s acolytes, Dylan grasped the totality of Guthrie’s vision. Beyond mimicry (and Dylan carefully emulated Woody’s accent, mannerisms, and poses), Dylan almost preternaturally understood the larger implication of Guthrie in ways that eluded other singers and writers at the time.2 As his career took off, however, Dylan began to slough off the more obvious Guthrieisms as he moved towards his electric-charged poetry of 1965-1966. -

Aaron Copland

9790051721474 Orchestra (score & parts) Aaron Copland John Henry 1940,rev.1952 4 min for orchestra 2(II=picc ad lib).2(1).2.2(1)-2.2.1.0-timp.perc:anvil/tgl/BD/SD/sand paper-pft(ad lib)-strings 9790051870714 (Parts) Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Aaron Copland photo © Roman Freulich Midday Thoughts Aaron Copland, arranged by David Del Tredici 2000 3 min CHAMBER ORCHESTRA for chamber ensemble Appalachian Spring 1(=picc.).2.2.bcl.2-2.0.0.0-strings Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Suite for 13 instruments 1970 25 min Music for Movies Chamber Suite 1942 16 min 1.0.1.1-0.0.0.0-pft-strings(2.2.2.2.1) for orchestra <b>NOTE:</b> An additional insert of section 7, "The Minister's Dance," is available for 1(=picc).1.1.1-1.2.1.0-timp.perc(1):glsp/xyl/susp.cym/tgl/BD/SD- performance. This version is called "Complete Ballet Suite for 13 Instruments." pft(harp)-strings 9790051096442 (Full score) 9790051094073 (Full score) Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world 9790051214297 Study Score - Hawkes Pocket Score 1429 9790051208760 Study Score - Hawkes Pocket Score 876 Music for the Theatre 9790051094066 (Full score) 1925 22 min Billy the Kid for chamber orchestra Waltz 1(=picc).1(=corA).1(=Eb).1-0.2.1.0-perc:glsp/xyl/cyms/wdbl/BD/SD- pft-strings 1938 4 min 9790051206995 Study Score - Hawkes Pocket Score 699 for chamber orchestra Availability: This work is available from Boosey -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

The Guardian.Pdf

My favourite film: Koyaanisqatsi By Leo Hickman December 13, 2011 It's a film without any characters, plot or narrative structure. And its title is notoriously hard to pronounce. What's not to love about Koyaanisqatsi? I came to Godfrey Reggio's 1982 masterpiece very late. It was actually during a Google search a few years back when looking for timelapse footage of urban traffic (for work rather than pleasure!) that I came across a "cult film", as some online reviewers were calling it. This meant I first watched it as all its loyal fans say not to: on DVD, on a small screen. If ever a film was destined for watching in a cinema, this is it. But, even without the luxury of full immersion, I was still truly captivated by it and, without any exaggeration, I still think about it every day. Koyaanisqatsi's formula is simple: combine the epic, remarkable cinematography of Ron Fricke with the swelling intensity and repeating motifs of Philip Glass's celebrated original score. There's your mood bomb, right there. But Reggio's directorial vision is key, too. He was the one who drove the project for six years on a small budget as he travelled with Fricke across the US in the mid-to-late 1970s, filming its natural and urban wonders with such originality. Koyaanisqatsi (1982) directed by Godfrey Reggio with music by Philip Glass. Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Guardian Personally, I view the film as the quintessential environmental movie – a transformative meditation on the current imbalance between humans and the wider world that supports them (in the Hopi language, "Koyanaanis" means turmoil and "qatsi" means life). -

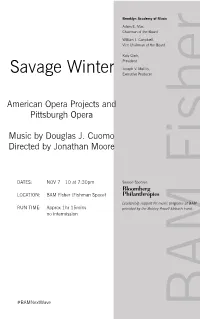

Savage Winter #Bamnextwave No Intermission LOCATION: RUN TIME: DATES: Pittsburgh Opera Approx 1Hr15mins BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) NOV 7—10At7:30Pm

Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Savage Winter Executive Producer American Opera Projects and Pittsburgh Opera Music by Douglas J. Cuomo Directed by Jonathan Moore DATES: NOV 7—10 at 7:30pm Season Sponsor: LOCATION: BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) Leadership support for music programs at BAM RUN TIME: Approx 1hr 15mins provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund. no intermission #BAMNextWave BAM Fisher Savage Winter Written and Composed by Music Director This project is supported in part by an Douglas J. Cuomo Alan Johnson award from the National Endowment for the Arts, and funding from The Andrew Text based on the poem Winterreise by Production Manager W. Mellon Foundation. Significant project Wilhelm Müller Robert Signom III support was provided by the following: Ms. Michele Fabrizi, Dr. Freddie and Directed by Production Coordinator Hilda Fu, The James E. and Sharon C. Jonathan Moore Scott H. Schneider Rohr Foundation, Steve & Gail Mosites, David & Gabriela Porges, Fund for New Performers Technical Director and Innovative Programming and The Protagonist: Tony Boutté (tenor) Sean E. West Productions, Dr. Lisa Cibik and Bernie Guitar/Electronics: Douglas J. Cuomo Kobosky, Michele & Pat Atkins, James Conductor/Piano: Alan Johnson Stage Manager & Judith Matheny, Diana Reid & Marc Trumpet: Sir Frank London Melissa Robilotta Chazaud, Francois Bitz, Mr. & Mrs. John E. Traina, Mr. & Mrs. Demetrios Patrinos, Scenery and properties design Assistant Director Heinz Endowments, R.K. Mellon Brandon McNeel Liz Power Foundation, Mr. & Mrs. William F. Benter, Amy & David Michaliszyn, The Estate of Video design Assistant Stage Manager Jane E. -

2005 Next Wave Festival

November 2005 2005 Next Wave Festival Mary Heilmann, Last Chance for Gas Study (detail), 2005 BAM 2005 Next Wave Festival is sponsored by: The PerformingNCOREArts Magazine Altria 2005 ~ext Wave FeslliLaL Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman William I. Campbell Chairman of the Board Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins Joseph V. Melillo President Executive Prod ucer presents Symphony No.6 (Plutonian Ode) & Symphony No.8 by Philip Glass Bruckner Orchestra Linz Approximate BAM Howard Gilman Opera House running time: Nov 2,4 & 5, 2005 at 7:30pm 1 hour, 40 minutes, one intermission Conducted by Dennis Russell Davies Soprano Lauren Flanigan Symphony No.8 - World Premiere I II III -intermission- Symphony No. 6 (Plutonian Ode) I II III BAM 2005 Next Wave Festival is sponsored by Altria Group, Inc. Major support for Symphonies 6 & 8 is provided by The Robert W Wilson Foundation, with additional support from the Austrian Cultural Forum New York. Support for BAM Music is provided by The Aaron Copland Fund for Music, Inc. Yamaha is the official piano for BAM. Dennis Russell Davies, Thomas Koslowski Horns Executive Director conductor Gerda Fritzsche Robert Schnepps Dr. Thomas Konigstorfer Aniko Biro Peter KeserU First Violins Severi n Endelweber Thomas Fischer Artistic Director Dr. Heribert Schroder Heinz Haunold, Karlheinz Ertl Concertmaster Cellos Walter Pauzenberger General Secretary Mario Seriakov, Elisabeth Bauer Christian Pottinger Mag. Catharina JUrs Concertmaster Bernhard Walchshofer Erha rd Zehetner Piotr Glad ki Stefa n Tittgen Florian Madleitner Secretary Claudia Federspieler Mitsuaki Vorraber Leopold Ramerstorfer Elisabeth Winkler Vlasta Rappl Susanne Lissy Miklos Nagy Bernadett Valik Trumpets Stage Crew Peter Beer Malva Hatibi Ernst Leitner Herbert Hoglinger Jana Mooshammer Magdalena Eichmeyer Hannes Peer Andrew Wiering Reinhard Pirstinger Thomas Wall Regina Angerer- COLUMBIA ARTISTS Yuko Kana-Buchmann Philipp Preimesberger BrUndlinger MANAGEMENT LLC Gorda na Pi rsti nger Tour Direction: Gudrun Geyer Double Basses Trombones R. -

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. CENTER FOR THE ARTS AT VIRGINIA TECH presents POWAQQATSI LIFE IN TRANSFORMATION The CANNON GROUP INC. A FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA and GEORGE LUCAS Presentation Music by Directed by PHILIP GLASS GODFREY REGGIO Photography by Edited by GRAHAM BERRY IRIS CAHN/ ALTON WALPOLE LEONIDAS ZOURDOUMIS Performed by PHILIP GLASS and the PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE conducted by Michael Riesman with the Blacksburg Children’s Chorale Patrice Yearwood, artistic director PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE Philip Glass, Lisa Bielawa, Dan Dryden, Stephen Erb, Jon Gibson, Michael Riesman, Mick Rossi, Andrew Sterman, David Crowell Guest Musicians: Ted Baker, Frank Cassara, Nelson Padgett, Yousif Sheronick The call to prayer in tonight’s performance is given by Dr. Khaled Gad Music Director MICHAEL RIESMAN Sound Design by Kurt Munkacsi Film Executive Producers MENAHEM GOLAN and YORAM GLOBUS Film Produced by MEL LAWRENCE, GODFREY REGGIO and LAWRENCE TAUB Production Management POMEGRANATE ARTS Linda Brumbach, Producer POWAQQATSI runs approximately 102 minutes and will be performed without intermission. SUBJECT TO CHANGE PO-WAQ-QA-TSI (from the Hopi language, powaq sorcerer + qatsi life) n. an entity, a way of life, that consumes the life forces of other beings in order to further its own life. POWAQQATSI is the second part of the Godfrey Reggio/Philip Glass QATSI TRILOGY. With a more global view than KOYAANISQATSI, Reggio and Glass’ first collaboration, POWAQQATSI, examines life on our planet, focusing on the negative transformation of land-based, human- scale societies into technologically driven, urban clones. -

Bruckner Orchester Linz

Bruckner Orchester Linz Dennis Russell Davies Conductor Martin Achrainer / Bass-Baritone Angélique Kidjo / Vocals Thursday Evening, February 2, 2017 at 7:30 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor 35th Performance of the 138th Annual Season 138th Annual Choral Union Series Tonight’s presenting sponsor is Michigan Medicine. Tonight’s supporting sponsor is the H. Gardner and Bonnie Ackley Endowment Fund. Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM, WRCJ 90.9 FM, Ann Arbor’s 107one, and WDET 101.9 FM. Special thanks to Tom Thompson of Tom Thompson Flowers, Ann Arbor, for his generous contribution of lobby floral art for this evening’s performance. The Bruckner Orchester Linz is the Philharmonic Orchestra of the State of Upper Austria, represented by Governor Dr. Josef Puehringer. The Bruckner Orchester Linz is supported by presto – friends of Bruckner Orchester. Bruckner Orchester Linz appears by arrangement with Columbia Artists Management, Inc. Angélique Kidjo appears by arrangement with Red Light Management. In consideration of the artists and the audience, please refrain from the use of electronic devices during the performance. The photography, sound recording, or videotaping of this performance is prohibited. PROGRAM George Gershwin, Arr. Morton Gould Porgy and Bess Suite Alexander Zemlinsky Symphonische Gesänge, Op. 20 Song from Dixieland Song of the Cotton Packer A Brown Girl Dead Bad Man Disillusion African Dance Arabesque Mr. Achrainer Intermission Duke Ellington, Arr. Maurice Peress Suite from Black, Brown, and Beige Black Brown Beige Philip Glass Ifè: Three Yorùbá Songs Olodumare Yemandja Oshumare Ms. Kidjo 3 PORGY AND BESS SUITE (1935, ARRANGED IN 1955) George Gershwin Born September 26, 1898 in Brooklyn, New York Died July 11, 1937 in Hollywood, California Arr. -

Production Database Updated As of 25Nov2020

American Composers Orchestra Works Performed Workshopped from 1977-2020 firstname middlename lastname Date eventype venue work title suffix premiere commission year written Michael Abene 4/25/04 Concert LGCH Improv ACO 2004 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Piano Improv Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Violin & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Double Bass & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/9/00 Concert CH Tomorrow's Song, as Yesterday Sings Today World 2000 Ricardo Lorenz Abreu 12/4/94 Concert CH Concierto para orquesta U.S. 1900 John Adams 4/25/83 Concert TULLY Shaker Loops World 1978 John Adams 1/11/87 Concert CH Chairman Dances, The New York ACO-Goelet 1985 John Adams 1/28/90 Concert CH Short Ride in a Fast Machine Albany Symphony 1986 John Adams 12/5/93 Concert CH El Dorado New York Fromm 1991 John Adams 5/17/94 Concert CH Tromba Lontana strings; 3 perc; hp; 2hn; 2tbn; saxophone1900 quartet John Adams 10/8/03 Concert CH Christian Zeal and Activity ACO 1973 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH The Wound-Dresser 1988 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH My Father Knew Charles Ives ACO 2003 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH Violin Concerto 1993 John Luther Adams 10/15/10 Concert ZANKL The Light Within World 2010 Victor Adan 10/16/11 Concert MILLR Tractus World 0 Judah Adashi 10/23/15 Concert ZANKL Sestina World 2015 Julia Adolphe 6/3/14 Reading FISHE Dark Sand, Sifting Light 2014 Kati Agocs 2/20/09 Concert ZANKL Pearls World 2008 Kati Agocs 2/22/09 Concert IHOUS