Angier Biddle Duke Interviewer: Frank Sieverts Date of Interview: May 1, 1964 Length: 28 Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King Faisal Assassinated

o.i> (Ejmttrrttrut iatlg (Sampita Serving Storrs Since 1896 VOL. LXXVIII NO. 102 STORRS, CONNECTICUT WEDNESDAY. MARCH 26. 1975 5 CENTS OFF CAMPUS King Faisal assassinated BEIRUT- (UPI) Saudi Khalid underwent heart surgery sacred cities of Mecca and monarch was wounded and Washington said the 31-year-old Arabi's King Faisal, spiritual in Cleveland, Ohio, three years Medina. hospitalized. Then. a .issassin was son of King Faisal's leader of the world's 600 million ago. t c a r - c h o k c d .innounccr half brother. Prince Musaid. The nephew walked the Moslems and master of the Faisal was killed while holding broadcast the news that Faisal Mideast's largest oil fields, was court in his Palace to mark the length of the hall apparently had died. Immediately all radio They said in 1966 he studied assassinated Tuesday as he sat on mniversary of the birth of intended to greet the seated King stations switched to readings of English at San Francisco State a golden chair in the mirrored Prophet Mohammed the with the customary kiss on both the Koran and thousands of College, and the following year hall of his palace by a deranged founder of the Islamic religion checks. Instead, he pulled a Saudis. (Tying and spreading he enrolled in a course in member of his own family. whose 600 million followers revolver from beneath his their arms in Uriel, surged into mechanical engineering at the Faisal, 68, died of wounds revered Faisal as their spiritual flowing robe and fired. the streets of Riyadh. -

Saudi Arabia Under King Faisal

SAUDI ARABIA UNDER KING FAISAL ABSTRACT || T^EsIs SubiviiTTEd FOR TIIE DEqREE of ' * ISLAMIC STUDIES ' ^ O^ilal Ahmad OZuttp UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. ABDUL ALI READER DEPARTMENT OF ISLAMIC STUDIES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1997 /•, •^iX ,:Q. ABSTRACT It is a well-known fact of history that ever since the assassination of capital Uthman in 656 A.D. the Political importance of Central Arabia, the cradle of Islam , including its two holiest cities Mecca and Medina, paled into in insignificance. The fourth Rashidi Calif 'Ali bin Abi Talib had already left Medina and made Kufa in Iraq his new capital not only because it was the main base of his power, but also because the weight of the far-flung expanding Islamic Empire had shifted its centre of gravity to the north. From that time onwards even Mecca and Medina came into the news only once annually on the occasion of the Haj. It was for similar reasons that the 'Umayyads 661-750 A.D. ruled form Damascus in Syria, while the Abbasids (750- 1258 A.D ) made Baghdad in Iraq their capital. However , after a long gap of inertia, Central Arabia again came into the limelight of the Muslim world with the rise of the Wahhabi movement launched jointly by the religious reformer Muhammad ibn Abd al Wahhab and his ally Muhammad bin saud, a chieftain of the town of Dar'iyah situated between *Uyayana and Riyadh in the fertile Wadi Hanifa. There can be no denying the fact that the early rulers of the Saudi family succeeded in bringing about political stability in strife-torn Central Arabia by fusing together the numerous war-like Bedouin tribes and the settled communities into a political entity under the banner of standard, Unitarian Islam as revived and preached by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. -

Us Military Assistance to Saudi Arabia, 1942-1964

DANCE OF SWORDS: U.S. MILITARY ASSISTANCE TO SAUDI ARABIA, 1942-1964 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bruce R. Nardulli, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2002 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Adviser Professor Peter L. Hahn _______________________ Adviser Professor David Stebenne History Graduate Program UMI Number: 3081949 ________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3081949 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ____________________________________________________________ ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The United States and Saudi Arabia have a long and complex history of security relations. These relations evolved under conditions in which both countries understood and valued the need for cooperation, but also were aware of its limits and the dangers of too close a partnership. U.S. security dealings with Saudi Arabia are an extreme, perhaps unique, case of how security ties unfolded under conditions in which sensitivities to those ties were always a central —oftentimes dominating—consideration. This was especially true in the most delicate area of military assistance. Distinct patterns of behavior by the two countries emerged as a result, patterns that continue to this day. This dissertation examines the first twenty years of the U.S.-Saudi military assistance relationship. It seeks to identify the principal factors responsible for how and why the military assistance process evolved as it did, focusing on the objectives and constraints of both U.S. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

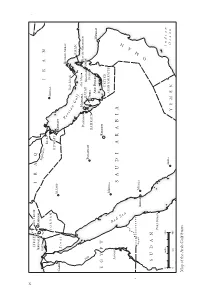

x ISRAEL WEST BANK IRAQ Jerusalem Amman Eup GAZA hrates IRAN Basra JORDAN Shiraz KUWAIT Al Jauf Kuwait Cairo Sinai P e Bandar Abbas r s i a Tunb Islands n G u OMAN l f Abu Musa Dammam Manama Ras Al-Khaimah N QATAR Ajman il Sharjah e Buraydah Dubai BAHRAIN Doha Abu Dhabi Muscat EGYPT Riyadh UNITED Medina ARAB EMIRATES R e Aswan d SAUDI ARABIA S e a N A Jeddah Mecca M O SUDAN Port Sudan 0 miles 250 Indian Abha Ocean 0 km 400 YEMEN Map of the Arab Gulf States 1. Muslim pilgrims circumambulate (tawaf ) the sacred Kaaba during sunrise after fajr prayer in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. 2. President Nixon and Mrs Nixon welcome King Faisal of Saudi Arabia on a visit to the United States in May 1971. 3. Henry Kissinger (left), the US Secretary of State, meets the Shah of Iran (right) in Zurich in early 1975. 4. Sheik Yamani talks about oil and the Palestinian problem during a press conference in Saudi Arabia in July 1979. 5. Crowds of Iranian protestors demonstrate in support of exiled Ayatollah Sayyid Ruhollah Khomeini in 1978, the year prior to the revolution. 6. Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein addresses members of his armed forces shortly before the invasion of Iran in September 1980. 7. Saudi Arabian soldiers prepare to load into armoured personnel carriers during clean-up operations following the Battle of Khafji, 2 February 1991. The Battle of Khafji was the first major ground engagement of the 1991 Gulf war. 8. Palestinian women demonstrate with Palestinian and Iraqi flags and portraits of Yasser Arafat and Saddam Hussein in the West Bank during the Kuwait crisis of 1990–91. -

Rivalry in the Middle East: the History of Saudi-Iranian Relations and Its Implications on American Foreign Policy

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Summer 2017 Rivalry in the Middle East: The History of Saudi-Iranian Relations and its Implications on American Foreign Policy Derika Weddington Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Weddington, Derika, "Rivalry in the Middle East: The History of Saudi-Iranian Relations and its Implications on American Foreign Policy" (2017). MSU Graduate Theses. 3129. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3129 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RIVALRY IN THE MIDDLE EAST: THE HISTORY OF SAUDI-IRANIAN RELATIONS AND ITS IMPLICATIONS ON AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Defense and Strategic Studies By Derika Weddington August 2017 RIVALARY IN THE MIDDLE EAST: THE HISTORY OF SAUDI-IRANIAN RELATIONS AND ITS IMPLICATIONS ON AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY Defense and Strategic Studies Missouri State University, August 2017 Master of Science Derika Weddington ABSTRACT The history of Saudi-Iranian relations has been fraught. -

I Historia De La Presidencia Del Consejo De Ministr Os

TOMO I 1820-1956 DEL CONSEJO DE MINISTROS HISTORIA DE LA PRESIDENCIA HISTORIA HISTORIA DE LA PRESIDENCIA DEL CONSEJO DE MINISTROS DEMOCRACIA Y BUEN GOBIERNO TOMO I (1820-1956) JOSÉ FRANCISCO GÁLVEZ MONTERO ENRIQUE SILVESTRE GARCÍA VEGA Lima, 2016 Historia de la Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros Democracia y Buen Gobierno Enrique Silvestre García Vega José Francisco Gálvez Montero ISBN: 978-87-93429-87-1 (versión e-book) Digitalizado y Distribuido por Saxo.com Perú S.A.C. www.saxo.com/es yopublico.saxo.com Telf: 51-1-221-9998 Dirección: Av. 2 de Mayo 534 Of. 304, Miraflores Lima-Perú Portada: Retratos de los ministros José María Raygada, Manuel Ortiz de Zevallos, Antonio Arenas y Alfredo Solf y Muro. Alegoria. Hecho el Depósito Legal en la Biblioteca Nacional del Perú N° 2016-07290 Editado por: Empresa Peruana de Servicios Editoriales S.A. Supervisión de diseño y diagramación: Daniel Chang Llerena Diseño de portada: Claudia del Pilar García Montoya Corrección de estilo: Jorge Coaguila Impreso en los talleres de la Empresa Peruana de Servicios Editoriales S.A. 2016 Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra. Ningún texto o imagen de esta edición puede, sin autorización de los autores, ser reproducido, copiado o transferido por cualquier medio impreso o electrónico, ya que se encuentra protegido por el Decreto Ley 822, Ley de los Derechos de Autor de la legislación peruana, así como normas internacionales vigentes. CONTENIDO TOMO I (1820-1956) Introducción 7 Metodología 9 CAPÍTULO I EL MINISTRO DE ESTADO ENTRE LA CONVICCIÓN -

Lumsden, George Quincy.Toc.Pdf

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR GEORGE QUINCEY LUMSDEN Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: January 11, 2000 Copyright 2006 A ST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in New Jersey Princeton University% Georgetown University US Navy Entered the Foreign Service in 1957 Educational Exchange Program Officer, New -ork .ity 1957-1959 State Department, FS0% German language studies 1959 01mir, Turkey% .onsular Officer 1959-1921 Environment 3arriage Government Bonn, Germany% Economic Officer 1922-1925 Export .ontrol President 6ennedy visit Junior .ircle of Bonn Diplomats Amman, Jordan% .hief of .onsular Section7Political Officer 1925-1927 Damascus anti-Assad demonstration 0mmigration visas US military assistance Environment Palestinians asser and Arab call for Arab Unity Arab-0srael 1927 war Riots Black September 6ing Hussein US Arab70srael Policy 1 Beirut, Lebanon, FS0% Arabic language studies 1927-1929 Environment Saudi students at American University of Beirut Ethnic and religious groups Palestinian refugees asser Arabic language program 6uwait% Economic Officer 1929-1972 Wealth Oil Production eutral 1one division Relations Education Environment Gulf Oil .ompany 0ran 0raq threat 6uwaitis Palestinians Egyptians British Border issues State Department% Desk Officer for 6uwait, Bahrain, Qatar 1972-1975 And United Arab Emirates Paris, France% Economic Officer 1975-1979 0nternational Petroleum Agency Oil .risis 0ranian Revolution France>s world role -

Saudi Aramco: National Flagship with Global Responsibilities

THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY RICE UNIVERSITY SAUDI ARAMCO: NATIONAL FLAGSHIP WITH GLOBAL RESPONSIBILITIES BY AMY MYERS JAFFE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY JAREER ELASS JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY PREPARED IN CONJUNCTION WITH AN ENERGY STUDY SPONSORED BY THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY AND JAPAN PETROLEUM ENERGY CENTER RICE UNIVERSITY – MARCH 2007 THIS PAPER WAS WRITTEN BY A RESEARCHER (OR RESEARCHERS) WHO PARTICIPATED IN THE JOINT BAKER INSTITUTE/JAPAN PETROLEUM ENERGY CENTER POLICY REPORT, THE CHANGING ROLE OF NATIONAL OIL COMPANIES IN INTERNATIONAL ENERGY MARKETS. WHEREVER FEASIBLE, THIS PAPER HAS BEEN REVIEWED BY OUTSIDE EXPERTS BEFORE RELEASE. HOWEVER, THE RESEARCH AND THE VIEWS EXPRESSED WITHIN ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL RESEARCHER(S) AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT THE VIEWS OF THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY NOR THOSE OF THE JAPAN PETROLEUM ENERGY CENTER. © 2007 BY THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY OF RICE UNIVERSITY THIS MATERIAL MAY BE QUOTED OR REPRODUCED WITHOUT PRIOR PERMISSION, PROVIDED APPROPRIATE CREDIT IS GIVEN TO THE AUTHOR AND THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY ABOUT THE POLICY REPORT THE CHANGING ROLE OF NATIONAL OIL COMPANIES IN INTERNATIONAL ENERGY MARKETS Of world proven oil reserves of 1,148 billion barrels, approximately 77% of these resources are under the control of national oil companies (NOCs) with no equity participation by foreign, international oil companies. The Western international oil companies now control less than 10% of the world’s oil and gas resource base. -

Apogeo Y Crisis De La Izquierda Peruana

APOGEO Y CRISIS DE LA IZQUIERDA PERUANA HABLAN SUS PROTAGONISTAS Alberto Adrianzén (Editor) Apogeo y crisis de la izquierda peruana. Hablan sus protagonistas. © Instituto para la Democracia y la Asistencia Electoral (IDEA Internacional) © Universidad Antonio Ruiz de Montoya (UARM) IDEA Internacional IDEA Internacional Universidad Antonio Ruiz de Montoya Strömsborg Oficina Región Andina Av. Paso de los Andes 970 – Pueblo Libre SE-103 34 Estocolmo Av. San Borja Norte 1123 Lima 21 / Perú Suecia San Borja, Lima 41-Perú Teléfono: (51 1) 719-5990 Tel.: +46 8 698 37 00 Tel.: +51 1 203 7960 www.uarm.edu.pe Fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Fax: +51 1 437 7227 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] librosuarm.blogspot.com www.idea.int Las opiniones expresadas en esta publicación no representan necesariamente los puntos de vista de IDEA Internacional ni de la Universidad Antonio Ruiz de Montoya, de sus juntas directivas ni de los miembros de sus consejos y/o Estados miembros. Esta publicación es independiente de ningún interés específico nacional o político. Toda solicitud de permisos para usar o traducir todo o alguna parte de esta publicación debe hacerse a: IDEA Internacional Universidad Antonio Ruiz de Montoya Strömsborg Av. Paso de los Andes 970 – Pueblo Libre SE-103 34 Estocolmo Lima 21 Perú Suecia Primera edición: diciembre de 2011 Tiraje: 1,000 ejemplares ISBN: 978-91-86565-47-3 Hecho el Depósito Legal en la Biblioteca Nacional del Perú Nº: 2011-16120 Foto de carátula: cortesía revista Caretas Impreso en el Perú por: MAD CORP. SAC Jr. -

May 15, 2012 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H2687 Koreans

May 15, 2012 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H2687 Koreans. I even had the privilege to work EXPRESSING SENSE OF HOUSE RE- (2) has characterized Iran as the ‘‘most ac- closely with the late Congressman Solarz, who GARDING IMPORTANCE OF PRE- tive state sponsor of terrorism’’; was Chairman of the East Asian and Pacific VENTING IRAN FROM ACQUIRING Whereas Iran has provided weapons, train- Affairs, the same subcommittee of which I am A NUCLEAR WEAPONS CAPA- ing, funding, and direction to terrorist the Ranking Member today. I am grateful for BILITY groups, including Hamas, Hezbollah, and Shi- ite militias in Iraq that are responsible for his leadership and understanding of the Asia Ms. ROS-LEHTINEN. Mr. Speaker, I the murders of hundreds of American forces Pacific region. move to suspend the rules and agree to and innocent civilians; Just as Ambassador Lilley and Congress- the resolution (H. Res. 568) expressing Whereas, on July 28, 2011, the Department man Solarz worked hard to protect the human the sense of the House of Representa- of the Treasury charged that the Govern- rights of the North Korean people, we must re- tives regarding the importance of pre- ment of Iran had forged a ‘‘secret deal’’ with main vigilant in helping the people of North venting the Government of Iran from al Qaeda to facilitate the movement of al Korea who struggle daily to escape the op- acquiring a nuclear weapons capa- Qaeda fighters and funding through Iranian pression and tyranny of the North Korean re- bility, as amended. territory; gime. The Clerk read the title of the resolu- Whereas in October 2011, senior leaders of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Again, I thank Chairwoman ROS-LEHTINEN tion. -

New York's Ticker Tape Parades Since the First Ticker-Tape Parade Was Held in 1886, Broadway Has Hosted 206 Marches

New York's Ticker Tape Parades Since the first ticker-tape parade was held in 1886, Broadway has hosted 206 marches. Each event is marked with a granite strip along the parade route—from the Battery to City Hall. Here is a comprehensive listing of each event: 1. October 28, 1886. Dedication of the Statue of Liberty 2. April 29, 1889. Centennial of George Washington's inauguration as first president of the United States 3. September 30, 1899. H Adm. George Dewey, hero of the Battle of Manila during the Spanish American War 4. June 18, 1910. Theodore Roosevelt, former President of the United States on his return from an African safari 5. May 9, 1917. Joseph J. C. Joffre, Marshal of France 6. September 8, 1919. Gen. John J. Pershing, Commander of the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I 7. October 3, 1919. Albert and Elizabeth, King and Queen of the Belgians 8. November 18, 1919. Edward Albert, Prince of Wales 9. October 19, 1921. Gen. Armando V. Diaz, Chief of Staff of the Italian army 10. October 21, 1921. Adm. Lord David Beatty, Commander of the British and Allied fleets during World War I 11. October 28, 1921. Ferdinand Foch, Marshal of France, Commander of the Allied armies during World War I 12. November 18, 1922. Georges Clemenceau, Premier of France during World War I 13. October 5, 1923. David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of Great Britain during World War I 14. August 6, 1924. U.S. Olympic athletes, on their return from the Paris Games 15. -

ZAPATA, Antonio. Pensando a La Derecha: Historia Intelectual Y Política

ZAPATA, Antonio. Pensando a la derecha: historia intelectual y política. Lima: Editorial Planeta Perú S. A., 2016, 199p. Recebido: 12-06-2018 Aprovado: 12-04-2019 Lucas Araújo Monte O livro “Pensando a la derecha” (2016) constitui uma síntese realizada por Antonio Zapata sobre a direita política peruana nos dias atuais. O autor é historiador, doutorado pela Universidade de Columbia em Nova York, professor universitário, analista político, além de colunista de um dos principais jornais do país – La República –, e membro do mais famoso think tank do Peru, o Instituto de Estudios Peruanos (IEP). Suas pesquisas são voltadas para o campo da história contemporânea e da realidade sociopolítica do seu país. Dado o período atual, em que a política na América Latina indica uma nova guinada para a direita, a obra demonstra uma grande relevância temática e uma contemporaneidade nas suas discussões. Ademais, são poucas as obras, de cunho acadêmico, que ousem abortar a direita como temática principal, além de raras as que o caráter crítico supere o próprio entendimento das ideias vinculadas a este polo do espectro político-ideológico. Zapata, já no primeiro parágrafo do livro, apresenta esse desafio por admitir ser um “esquerdista” convicto e confesso. No entanto, as suas convicções não atrapalham em nada o seu objetivo, uma vez que adota uma metodologia de, primeiramente, apresentar as ideias envolvidas em torno de determinada agremiação política, para, num segundo momento, se for o caso, tecer algum comentário crítico. Portanto, a obra, apesar de retratar de uma maneira objetiva as ideias e a ação política em torno dos principais partidos políticos da direita peruana, não perde o seu caráter crítico.