The Axiom of Choice and Related Topics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematics I Basic Mathematics

Mathematics I Basic Mathematics Prepared by Prof. Jairus. Khalagai African Virtual university Université Virtuelle Africaine Universidade Virtual Africana African Virtual University NOTICE This document is published under the conditions of the Creative Commons http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creative_Commons Attribution http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/ License (abbreviated “cc-by”), Version 2.5. African Virtual University Table of ConTenTs I. Mathematics 1, Basic Mathematics _____________________________ 3 II. Prerequisite Course or Knowledge _____________________________ 3 III. Time ____________________________________________________ 3 IV. Materials _________________________________________________ 3 V. Module Rationale __________________________________________ 4 VI. Content __________________________________________________ 5 6.1 Overview ____________________________________________ 5 6.2 Outline _____________________________________________ 6 VII. General Objective(s) ________________________________________ 8 VIII. Specific Learning Objectives __________________________________ 8 IX. Teaching and Learning Activities ______________________________ 10 X. Key Concepts (Glossary) ____________________________________ 16 XI. Compulsory Readings ______________________________________ 18 XII. Compulsory Resources _____________________________________ 19 XIII. Useful Links _____________________________________________ 20 XIV. Learning Activities _________________________________________ 23 XV. Synthesis Of The Module ___________________________________ -

1 Elementary Set Theory

1 Elementary Set Theory Notation: fg enclose a set. f1; 2; 3g = f3; 2; 2; 1; 3g because a set is not defined by order or multiplicity. f0; 2; 4;:::g = fxjx is an even natural numberg because two ways of writing a set are equivalent. ; is the empty set. x 2 A denotes x is an element of A. N = f0; 1; 2;:::g are the natural numbers. Z = f:::; −2; −1; 0; 1; 2;:::g are the integers. m Q = f n jm; n 2 Z and n 6= 0g are the rational numbers. R are the real numbers. Axiom 1.1. Axiom of Extensionality Let A; B be sets. If (8x)x 2 A iff x 2 B then A = B. Definition 1.1 (Subset). Let A; B be sets. Then A is a subset of B, written A ⊆ B iff (8x) if x 2 A then x 2 B. Theorem 1.1. If A ⊆ B and B ⊆ A then A = B. Proof. Let x be arbitrary. Because A ⊆ B if x 2 A then x 2 B Because B ⊆ A if x 2 B then x 2 A Hence, x 2 A iff x 2 B, thus A = B. Definition 1.2 (Union). Let A; B be sets. The Union A [ B of A and B is defined by x 2 A [ B if x 2 A or x 2 B. Theorem 1.2. A [ (B [ C) = (A [ B) [ C Proof. Let x be arbitrary. x 2 A [ (B [ C) iff x 2 A or x 2 B [ C iff x 2 A or (x 2 B or x 2 C) iff x 2 A or x 2 B or x 2 C iff (x 2 A or x 2 B) or x 2 C iff x 2 A [ B or x 2 C iff x 2 (A [ B) [ C Definition 1.3 (Intersection). -

Axioms and Algebraic Systems*

Axioms and algebraic systems* Leong Yu Kiang Department of Mathematics National University of Singapore In this talk, we introduce the important concept of a group, mention some equivalent sets of axioms for groups, and point out the relationship between the individual axioms. We also mention briefly the definitions of a ring and a field. Definition 1. A binary operation on a non-empty set S is a rule which associates to each ordered pair (a, b) of elements of S a unique element, denoted by a* b, in S. The binary relation itself is often denoted by *· It may also be considered as a mapping from S x S to S, i.e., * : S X S ~ S, where (a, b) ~a* b, a, bE S. Example 1. Ordinary addition and multiplication of real numbers are binary operations on the set IR of real numbers. We write a+ b, a· b respectively. Ordinary division -;- is a binary relation on the set IR* of non-zero real numbers. We write a -;- b. Definition 2. A binary relation * on S is associative if for every a, b, c in s, (a* b) * c =a* (b *c). Example 2. The binary operations + and · on IR (Example 1) are as sociative. The binary relation -;- on IR* (Example 1) is not associative smce 1 3 1 ~ 2) ~ 3 _J_ - 1 ~ (2 ~ 3). ( • • = -6 I 2 = • • * Talk given at the Workshop on Algebraic Structures organized by the Singapore Mathemat- ical Society for school teachers on 5 September 1988. 11 Definition 3. A semi-group is a non-€mpty set S together with an asso ciative binary operation *, and is denoted by (S, *). -

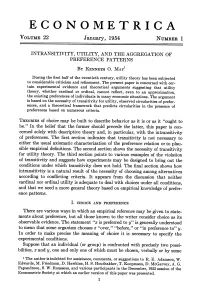

Intransitivity, Utility, and the Aggregation of Preference Patterns

ECONOMETRICA VOLUME 22 January, 1954 NUMBER 1 INTRANSITIVITY, UTILITY, AND THE AGGREGATION OF PREFERENCE PATTERNS BY KENNETH 0. MAY1 During the first half of the twentieth century, utility theory has been subjected to considerable criticism and refinement. The present paper is concerned with cer- tain experimental evidence and theoretical arguments suggesting that utility theory, whether cardinal or ordinal, cannot reflect, even to an approximation, the existing preferences of individuals in many economic situations. The argument is based on the necessity of transitivity for utility, observed circularities of prefer- ences, and a theoretical framework that predicts circularities in the presence of preferences based on numerous criteria. THEORIES of choice may be built to describe behavior as it is or as it "ought to be." In the belief that the former should precede the latter, this paper is con- cerned solely with descriptive theory and, in particular, with the intransitivity of preferences. The first section indicates that transitivity is not necessary to either the usual axiomatic characterization of the preference relation or to plau- sible empirical definitions. The second section shows the necessity of transitivity for utility theory. The third section points to various examples of the violation of transitivity and suggests how experiments may be designed to bring out the conditions under which transitivity does not hold. The final section shows how intransitivity is a natural result of the necessity of choosing among alternatives according to conflicting criteria. It appears from the discussion that neither cardinal nor ordinal utility is adequate to deal with choices under all conditions, and that we need a more general theory based on empirical knowledge of prefer- ence patterns. -

Cantor on Infinity in Nature, Number, and the Divine Mind

Cantor on Infinity in Nature, Number, and the Divine Mind Anne Newstead Abstract. The mathematician Georg Cantor strongly believed in the existence of actually infinite numbers and sets. Cantor’s “actualism” went against the Aristote- lian tradition in metaphysics and mathematics. Under the pressures to defend his theory, his metaphysics changed from Spinozistic monism to Leibnizian volunta- rist dualism. The factor motivating this change was two-fold: the desire to avoid antinomies associated with the notion of a universal collection and the desire to avoid the heresy of necessitarian pantheism. We document the changes in Can- tor’s thought with reference to his main philosophical-mathematical treatise, the Grundlagen (1883) as well as with reference to his article, “Über die verschiedenen Standpunkte in bezug auf das aktuelle Unendliche” (“Concerning Various Perspec- tives on the Actual Infinite”) (1885). I. he Philosophical Reception of Cantor’s Ideas. Georg Cantor’s dis- covery of transfinite numbers was revolutionary. Bertrand Russell Tdescribed it thus: The mathematical theory of infinity may almost be said to begin with Cantor. The infinitesimal Calculus, though it cannot wholly dispense with infinity, has as few dealings with it as possible, and contrives to hide it away before facing the world Cantor has abandoned this cowardly policy, and has brought the skeleton out of its cupboard. He has been emboldened on this course by denying that it is a skeleton. Indeed, like many other skeletons, it was wholly dependent on its cupboard, and vanished in the light of day.1 1Bertrand Russell, The Principles of Mathematics (London: Routledge, 1992 [1903]), 304. -

Natural Numerosities of Sets of Tuples

TRANSACTIONS OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 367, Number 1, January 2015, Pages 275–292 S 0002-9947(2014)06136-9 Article electronically published on July 2, 2014 NATURAL NUMEROSITIES OF SETS OF TUPLES MARCO FORTI AND GIUSEPPE MORANA ROCCASALVO Abstract. We consider a notion of “numerosity” for sets of tuples of natural numbers that satisfies the five common notions of Euclid’s Elements, so it can agree with cardinality only for finite sets. By suitably axiomatizing such a no- tion, we show that, contrasting to cardinal arithmetic, the natural “Cantorian” definitions of order relation and arithmetical operations provide a very good algebraic structure. In fact, numerosities can be taken as the non-negative part of a discretely ordered ring, namely the quotient of a formal power series ring modulo a suitable (“gauge”) ideal. In particular, special numerosities, called “natural”, can be identified with the semiring of hypernatural numbers of appropriate ultrapowers of N. Introduction In this paper we consider a notion of “equinumerosity” on sets of tuples of natural numbers, i.e. an equivalence relation, finer than equicardinality, that satisfies the celebrated five Euclidean common notions about magnitudines ([8]), including the principle that “the whole is greater than the part”. This notion preserves the basic properties of equipotency for finite sets. In particular, the natural Cantorian definitions endow the corresponding numerosities with a structure of a discretely ordered semiring, where 0 is the size of the emptyset, 1 is the size of every singleton, and greater numerosity corresponds to supersets. This idea of “Euclidean” numerosity has been recently investigated by V. -

A List of Arithmetical Structures Complete with Respect to the First

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Theoretical Computer Science 257 (2001) 115–151 www.elsevier.com/locate/tcs A list of arithmetical structures complete with respect to the ÿrst-order deÿnability Ivan Korec∗;X Slovak Academy of Sciences, Mathematical Institute, Stefanikovaà 49, 814 73 Bratislava, Slovak Republic Abstract A structure with base set N is complete with respect to the ÿrst-order deÿnability in the class of arithmetical structures if and only if the operations +; × are deÿnable in it. A list of such structures is presented. Although structures with Pascal’s triangles modulo n are preferred a little, an e,ort was made to collect as many simply formulated results as possible. c 2001 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. MSC: primary 03B10; 03C07; secondary 11B65; 11U07 Keywords: Elementary deÿnability; Pascal’s triangle modulo n; Arithmetical structures; Undecid- able theories 1. Introduction A list of (arithmetical) structures complete with respect of the ÿrst-order deÿnability power (shortly: def-complete structures) will be presented. (The term “def-strongest” was used in the previous versions.) Most of them have the base set N but also structures with some other universes are considered. (Formal deÿnitions are given below.) The class of arithmetical structures can be quasi-ordered by ÿrst-order deÿnability power. After the usual factorization we obtain a partially ordered set, and def-complete struc- tures will form its greatest element. Of course, there are stronger structures (with respect to the ÿrst-order deÿnability) outside of the class of arithmetical structures. -

Basic Concepts of Set Theory, Functions and Relations 1. Basic

Ling 310, adapted from UMass Ling 409, Partee lecture notes March 1, 2006 p. 1 Basic Concepts of Set Theory, Functions and Relations 1. Basic Concepts of Set Theory........................................................................................................................1 1.1. Sets and elements ...................................................................................................................................1 1.2. Specification of sets ...............................................................................................................................2 1.3. Identity and cardinality ..........................................................................................................................3 1.4. Subsets ...................................................................................................................................................4 1.5. Power sets .............................................................................................................................................4 1.6. Operations on sets: union, intersection...................................................................................................4 1.7 More operations on sets: difference, complement...................................................................................5 1.8. Set-theoretic equalities ...........................................................................................................................5 Chapter 2. Relations and Functions ..................................................................................................................6 -

Binary Operations

4-22-2007 Binary Operations Definition. A binary operation on a set X is a function f : X × X → X. In other words, a binary operation takes a pair of elements of X and produces an element of X. It’s customary to use infix notation for binary operations. Thus, rather than write f(a, b) for the binary operation acting on elements a, b ∈ X, you write afb. Since all those letters can get confusing, it’s also customary to use certain symbols — +, ·, ∗ — for binary operations. Thus, f(a, b) becomes (say) a + b or a · b or a ∗ b. Example. Addition is a binary operation on the set Z of integers: For every pair of integers m, n, there corresponds an integer m + n. Multiplication is also a binary operation on the set Z of integers: For every pair of integers m, n, there corresponds an integer m · n. However, division is not a binary operation on the set Z of integers. For example, if I take the pair 3 (3, 0), I can’t perform the operation . A binary operation on a set must be defined for all pairs of elements 0 from the set. Likewise, a ∗ b = (a random number bigger than a or b) does not define a binary operation on Z. In this case, I don’t have a function Z × Z → Z, since the output is ambiguously defined. (Is 3 ∗ 5 equal to 6? Or is it 117?) When a binary operation occurs in mathematics, it usually has properties that make it useful in con- structing abstract structures. -

I Want to Start My Story in Germany, in 1877, with a Mathematician Named Georg Cantor

LISTENING - Ron Eglash is talking about his project http://www.ted.com/talks/ 1) Do you understand these words? iteration mission scale altar mound recursion crinkle 2) Listen and answer the questions. 1. What did Georg Cantor discover? What were the consequences for him? 2. What did von Koch do? 3. What did Benoit Mandelbrot realize? 4. Why should we look at our hand? 5. What did Ron get a scholarship for? 6. In what situation did Ron use the phrase “I am a mathematician and I would like to stand on your roof.” ? 7. What is special about the royal palace? 8. What do the rings in a village in southern Zambia represent? 3)Listen for the second time and decide whether the statements are true or false. 1. Cantor realized that he had a set whose number of elements was equal to infinity. 2. When he was released from a hospital, he lost his faith in God. 3. We can use whatever seed shape we like to start with. 4. Mathematicians of the 19th century did not understand the concept of iteration and infinity. 5. Ron mentions lungs, kidney, ferns, and acacia trees to demonstrate fractals in nature. 6. The chief was very surprised when Ron wanted to see his village. 7. Termites do not create conscious fractals when building their mounds. 8. The tiny village inside the larger village is for very old people. I want to start my story in Germany, in 1877, with a mathematician named Georg Cantor. And Cantor decided he was going to take a line and erase the middle third of the line, and take those two resulting lines and bring them back into the same process, a recursive process. -

Georg Cantor English Version

GEORG CANTOR (March 3, 1845 – January 6, 1918) by HEINZ KLAUS STRICK, Germany There is hardly another mathematician whose reputation among his contemporary colleagues reflected such a wide disparity of opinion: for some, GEORG FERDINAND LUDWIG PHILIPP CANTOR was a corruptor of youth (KRONECKER), while for others, he was an exceptionally gifted mathematical researcher (DAVID HILBERT 1925: Let no one be allowed to drive us from the paradise that CANTOR created for us.) GEORG CANTOR’s father was a successful merchant and stockbroker in St. Petersburg, where he lived with his family, which included six children, in the large German colony until he was forced by ill health to move to the milder climate of Germany. In Russia, GEORG was instructed by private tutors. He then attended secondary schools in Wiesbaden and Darmstadt. After he had completed his schooling with excellent grades, particularly in mathematics, his father acceded to his son’s request to pursue mathematical studies in Zurich. GEORG CANTOR could equally well have chosen a career as a violinist, in which case he would have continued the tradition of his two grandmothers, both of whom were active as respected professional musicians in St. Petersburg. When in 1863 his father died, CANTOR transferred to Berlin, where he attended lectures by KARL WEIERSTRASS, ERNST EDUARD KUMMER, and LEOPOLD KRONECKER. On completing his doctorate in 1867 with a dissertation on a topic in number theory, CANTOR did not obtain a permanent academic position. He taught for a while at a girls’ school and at an institution for training teachers, all the while working on his habilitation thesis, which led to a teaching position at the university in Halle. -

The Z of ZF and ZFC and ZF¬C

From SIAM News , Volume 41, Number 1, January/February 2008 The Z of ZF and ZFC and ZF ¬C Ernst Zermelo: An Approach to His Life and Work. By Heinz-Dieter Ebbinghaus, Springer, New York, 2007, 356 pages, $64.95. The Z, of course, is Ernst Zermelo (1871–1953). The F, in case you had forgotten, is Abraham Fraenkel (1891–1965), and the C is the notorious Axiom of Choice. The book under review, by a prominent logician at the University of Freiburg, is a splendid in-depth biography of a complex man, a treatment that shies away neither from personal details nor from the mathematical details of Zermelo’s creations. BOOK R EV IEW Zermelo was a Berliner whose early scientific work was in applied By Philip J. Davis mathematics: His PhD thesis (1894) was in the calculus of variations. He had thought about this topic for at least ten additional years when, in 1904, in collaboration with Hans Hahn, he wrote an article on the subject for the famous Enzyclopedia der Mathematische Wissenschaften . In point of fact, though he is remembered today primarily for his axiomatization of set theory, he never really gave up applications. In his Habilitation thesis (1899), Zermelo was arguing with Ludwig Boltzmann about the foun - dations of the kinetic theory of heat. Around 1929, he was working on the problem of the path of an airplane going in minimal time from A to B at constant speed but against a distribution of winds. This was a problem that engaged Levi-Civita, von Mises, Carathéodory, Philipp Frank, and even more recent investigators.