The Akademia Zamojska: Shaping a Renaissance University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Akademia Zamojska: Shaping a Renaissance University

Chapter 1 The Akademia Zamojska: Shaping a Renaissance University 1 Universities in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth In the course of the sixteenth century, in the territory initially under the juris- diction of Poland and, from 1569 on, of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, three centres of higher education were established that could boast the status of university. The first to be founded, in 1544, was the academy of Königsberg, known as the Albertina after the first Duke of Prussia, Albert of Hohenzollern. In actual fact, like other Polish gymnasia established in what was called Royal Prussia, the dominant cultural influence over this institution, was German, although the site purchased by the Duke on which it was erected was, at the time, a feud of Poland.1 It was indeed from Sigismund ii Augustus of Poland that the academy received the royal privilege in 1560, approval which – like the papal bull that was never ac- tually issued – was necessary for obtaining the status of university. However, in jurisdictional terms at least, the university was Polish for only one century, since from 1657 it came under direct Prussian control. It went on to become one of the most illustrious German institutions, attracting academics of international and enduring renown including the philosophers Immanuel Kant and Johann Gottlieb Fichte. The Albertina was conceived as an emanation of the University of Marburg and consequently the teaching body was strictly Protestant, headed by its first rector, the poet and professor of rhetoric Georg Sabinus (1508–1560), son-in-law of Philip Melanchthon. When it opened, the university numbered many Poles and Lithuanians among its students,2 and some of its most emi- nent masters were also Lithuanian, such as the professor of Greek and Hebrew 1 Karin Friedrich, The Other Prussia (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000), 20–45, 72–74. -

Destination:Poland

Destination: Poland The Guide Tomasz Ławecki Kazimierz Kunicki Liliana Olchowik-Adamowska Destination: Poland The Guide Tomasz Ławecki Kazimierz Kunicki Liliana Olchowik-Adamowska Destination: Poland The Guide Not just museums: the living A place in the heart of Europe 8 I IX folklore in Poland 490 A chronicle of Poland: Communing with nature: Poland’s II a stroll down the ages 20 X national parks and beyond 522 Sanctuares, rites, pilgrimages – Famous Poles 86 III XI the traditional religious life 564 IV Gateways to Poland 138 XII Poland for the active 604 V Large Cities 182 XIII Things Will Be Happening 624 Destination: Medium-sized towns 304 VI XIV Castles, churches, prehistory 666 Small is beautiful – Practical Information 718 VII Poland’s lesser towns 366 XV The UNESCO World Heritage List Index of place names 741 VIII in Poland 434 XVI Not just museums: the living A place in the heart of Europe 8 I IX folklore in Poland 490 A chronicle of Poland: Communing with nature: Poland’s II a stroll down the ages 20 X national parks and beyond 522 Sanctuares, rites, pilgrimages – Famous Poles 86 III XI the traditional religious life 564 IV Gateways to Poland 138 XII Poland for the active 604 V Large Cities 182 XIII Things Will Be Happening 624 Destination: Medium-sized towns 304 VI XIV Castles, churches, prehistory 666 Small is beautiful – Practical Information 718 VII Poland’s lesser towns 366 XV The UNESCO World Heritage List Index of place names 741 VIII in Poland 434 XVI Text Tomasz Ławecki POLAND Kazimierz Kunicki and the other Liliana -

Rozdział (200.3Kb)

Mariusz KULESZA Dorota KACZYŃSKA Department of Political Geography and Regional Studies University of Łódź, POLAND No. 11 MULTINATIONAL CULTURAL HERITAGE OF THE EASTERN PART OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF POLAND AND LITHUANIA Poland is a country with the largest territorial variation in the history of Europe. These changes involved not only the temporary gaining and losing some provinces that were later regained (as was the case for most European countries), but a transition of the country from its natural geographical frames deep into neighbouring ecumenes, while losing its own historical borders in the process. There were also times when the Polish state would disappear from the map of Europe for extended periods. Poland is also a country which for centuries was a place for foreigners where foreigners settled, lead here by various reasons, and left their mark, to a smaller or greater extent in the country's history. They also left numerous places in the Republic that became important not only for Poles. Today, these places belong to both Polish and non-Polish cultures and they become a very significant element of our cultural heritage, a deposit within Polish borders. Up until mid-14th century, Poland was a medium-sized, mostly ethnically homogenous country which faced west both culturally and economically. The eastern border of the country was also the border of Latin Christianity, with the Orthodox Ruthenia and Pagan Lithuania beyond it. In the second half of the 14th century, this situation changed significantly. First, the Red Ruthenia and Podolia were annexed by Poland, and another breakthrough came with the union with Lithuania, which was a Eastern European superpower back then. -

Maquetacišn 1

A New Strategy of Preservation of The Ideal Renaissance Town of Zamosc in Poland Alicja Szmelter Warsaw University of Technology, Faculty of Architecture, Warsaw. Poland The paper will present and discuss a new strategy proposed for the preservation of Zamosc. Zamosc with its 50 thousand inhabitants is a rather small, provincial town of Poland, situated far from the main trading roads in the southeastern part of the country, near to the Polish-Ukrainian border. Despite its size and remote location the Polish and international specialists have recognized the unique value of its Old Town, as a rare example of the Renaissance ideal town, and in 2002 Zamosc was listed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. The Renaissance Old Town was developed mainly in the 16th and 17th centuries and left almost untouched in its historic form till today. Consequently, plans to develop it are drawing exceptional attention from the Polish urban planners and conservationists A new strategy to preserve and maintain the cultural heritage of Zamosc is based on the principle that the Old Town should be a source of funds for the town, rather than of consuming its budget. Some basic principles of the strategy for the Old Town of Zamosc. The strategy is a continuation of the earlier, recently executed plan allowed by easing of the earlier conservationist restrictions. For instance, new attractive building lots have been provided in a historic core with the aim of attracting the developers to invest in the Old Town. The lots were not built on since the erection of the town in the 16th century. -

A Review of Methods of Cartographic Presentation of Urban Space

E3S Web of Conferences 55, 00003 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/20185500003 XXIIIrd Autumn School of Geodesy A review of methods of cartographic presentation of urban space Joanna Bac-Bronowicz1,*,and Gabriela Wojciechowska1 1Wroclaw University of Science and Technology, Faculty of Geoengineering, Mining and Geology, 27 Wyb. Wyspianskiego St., 50-370 Wroclaw, Poland Abstract. The aim of the article is to present selected solutions applied in urban planning, which, even contemporarily, can be used as models. The paper presents a review of selected concepts of model cities from the antiquity to contemporary times. The article presents methods of creating three-dimensional city models (or their flat presentations in so-called two and a half dimensions), including the historical conceptualization, portraying both the practical and aesthetical features of former map projections. Referring to historical examples, the article also includes historical and contemporary urban 3D models corresponding to analyzed conceptions. 1 Introduction cartographic representation are endless. Changes in remote sensing made it possible to collect increasingly Portraying of the surrounding reality has been an accurate 3D data concerning the environment, as well as immanent element of our civilization since its information about new products and services in 4D. It is beginnings. Since the prehistory, depending on the believed that a number of changes in cartography during predominant aesthetic movement, the imagery of the next five to ten years will be caused by 4D surrounding environment was presented through the cartographic products [3]. means of cave paintings, rock reliefs (Fig. 1), as well as It is believed that the increase of urbanization will paintings in interiors of temples and other structures. -

"Zamojsko-Wołyńskie Zeszyty Muzealne" Wydawane Są We Współpracy Z Wołyńskim Muzeum Krajoznawczym W Łucku. Na

"Zamojsko-Wołyńskie Zeszyty Muzealne" wydawane są we współpracy z Wołyńskim Muzeum Krajoznawczym w Łucku. Na łamach periodyku publikujemy wyniki badań dotyczących szeroko pojętej historii i kultury terenów pogranicza oraz opracowania zbiorów muzealnych. Autorami publikacji są pracownicy Muzeum Zamojskiego w Zamościu Wołyńskiego Muzeum Krajoznawczego w Łucku oraz zaproszeni do współpracy specjaliści z prezentowanych w wydawnictwie dziedzin ze środowisk uniwersyteckich, krajoznawczych i muzealnych. Materiały publikowane są w wersjach autorskich. Ze względu na stosowane przez autorów różne systemy sporządzania przypisów i bibliografii oraz trudności w ich ujednoliceniu pozostawiamy je w wersji oryginalnej. Redakcja nie bierze pełnej odpowiedzialności za treści merytoryczne zamieszczone w artykułach. Zespół redakcyjny "Zamojsko-Wołyńskich Zeszytów Muzealnych" Piotr Kondraciuk, Jerzy Kuśnierz Силюк Анатолій М.., Andrzej Urbański Redakcja tomu Piotr Kondraciuk, Jerzy Kuśnierz, Andrzej Urbański Korekta Piotr Kondraciuk, Jerry Kuśnierz, Силюк Анатолій М Tłumaczenia tekstów z języka ukraińskiego na język polski Piotr Kondraciuk, Jerzy Kuśnierz, Силюк Анатолій М z języka polskiego na na język ukraiński Силюк Анатолій М streszczenia w języku angielskim Joanna Paczos Konsultacja filologiczna Andrzej Prawica Autor wystawy "Twierdze kresowe Rzeczypospolitej" Jacek Feduszka Na okładce Ostróg, Wieża Nowa (Okrągła). Fot. J. Kuśnierz. Projekt okładki Piotr Kondraciuk ISSN: 83-1733-8972 ISSN: 1733-8972Publikacja przygotowana i finansowana ze środków Unii Europejskiej w ramach grantu z Funduszu Małych Projektów Phare zarządzanego przez Euroregion Bug. Projekt "Pogranicza Europy". Autor projektu: Piotr Kondraciuk Druk: Zakład Poligraficzny, Zamość, ul. B. Prusa 19, tel. (0-84) 639 23 18 4 Biskup Mariusz Leszczyński Zamość Jaśniał cnotami przed Bogiem i ludźmi Kazanie wygłoszone 3 czerwca 2005 w katedrze zamojskiej z okazji 400-lecie śmierci kanclerza i hetmana Jan Zamoyskiego (1542-1605) (2 Krl 5.1-5, 9-10,14-15, Ap 14. -

6. Zamość, Historical and Conservation Notes

6. Zamość, historical and conservation notes Calogero Bellanca In Poland, in the seventh decade of 16th century, while the aim of the diplomatic activity and the military politic of the sovereigns is the maintenance of good reports with the German emperor, the initiative of foundation of new cities in the oriental territory of the country is intensified, reinvigorating without many changes the praxis used in the Middle Ages (1). These are the years when an architect with Paduan origins, Bernardo Morando, starts his activity, and he deserves an important position in the History of Architecture in Poland. From 1569 he was in Warsaw. There are indeed some news of this period about his participation on the enlargement of the Royal Castle of the city (1569-1573) (2). His presence in Warsaw finds an explanation in the favorable moment for the construction in the city, chosen by the royal family to stay. After the death of Sigismondo Augusto, Morando left the city as he couldn’t find more working chances. He went to Lwow (3), where he met for the first time the Chancellor of the Kingdom, Jan Zamoyski, in July 1578. From this date and for twenty-five years, an ideal relationship was born between the artist and the patron. The assignment of building a whole city confirms the hypothesis of the quality of the precedent works (4). However, we shouldn’t forget that the Paduan origins of Morando influenced the Jan Zamoyski’s choices. When he was young he had studied in Padova and he had been elected as the Head of the Legal Department, for being one of the principal scholars of the Classical Antiquity and one of the most relevant figures of the history of culture in Poland, representing the model of the “universal man” of the Cinquecento. -

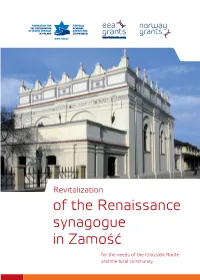

Of the Renaissance Synagogue in Zamość for the Needs of the Chassidic Route and the Local Community 3

1 Revitalization of the Renaissance synagogue in Zamość for the needs of the Chassidic Route and the local community 3 ABOUT THE FOUNDATION The Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland was founded in 2002 by the Union of Jewish Communities in Poland and the World Jewish Restitution Organization (WJRO). The Foundation’s mission is to protect surviving monuments of Jewish heritage in Poland. Our chief task is the protection of Jewish cemeteries. In cooperation with other organizations and private donors we have saved from destruction, fenced and commemorated several burial grounds (in Zakopane, Kozienice, Mszczonów, Iwaniska, Strzegowo, Dubienka, Kolno, Iłża, Wysokie Mazow- th The official opening of the “Synagogue” Center on April 5 , 2011, was held under the honor- ieckie, Siedleczka-Kańczuga, Żuromin and several other localities). Our activities also include the ary patronage of the President of the Republic of Poland, Bronisław Komorowski. renovation and revitalization of Jewish monuments of special significance, such as the synagogues in Kraśnik, Przysucha and Rymanów as well as the synagogue in Zamość. However, the protection of material patrimony is not the Foundation’s only task. We are equally concerned about increasing public knowledge regarding the history of Polish Jews, whose contribu- This brochure has been published within the framework of the project “Revitalization of the Renaissance synagogue in tion to Poland’s heritage spans several centuries. Our most important educational projects include Zamość for the needs of the Chassidic Route and the local community” implemented by the Foundation for the Preserva- tion of Jewish Heritage in Poland and supported by a grant from Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway through the EEA the “To Bring Memory Back” program, addressed to high school students, and POLIN – Polish Jews’ Financial Mechanism and the Norwegian Financial Mechanism. -

RENAISSANCE SYNAGOGUE in ZAMOŚĆ for the Needs of the Chassidic Route and the Local Community 3

1 REVITALIZATION OF THE RENAISSANCE SYNAGOGUE IN ZAMOŚĆ for the needs of the Chassidic Route and the local community 3 ABOUT THE FOUNDATION �e Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland was founded in 2002 by the Union of Jewish Communities in Poland and the World Jewish Restitution Organization (WJRO). �e Foundation’s mission is to protect surviving monuments of Jewish heritage in Poland. Our chief task is the protection of Jewish cemeteries – in cooperation with other organizations and private donors we have saved from destruction, fenced and commemorated several burial grounds (in Zakopane, Kozienice, Mszczonów, Iwaniska, Strzegowo, Dubienka, Kolno, Iłża, Wysokie Mazowieckie, Siedleczka-Kańczuga, Żuromin and several other places). Our activities also include the renovation and revitalization of particularly important Jewish monuments, such as the synagogues in Kraśnik, Przysucha and Rymanów as well as the synagogue in Zamość. �is brochure has been published within the framework of the project “Revitalization of the Renaissance synagogue in Zamość for the needs of the Chassidic Route and the local community” implemented by the Foundation for the �e protection of material patrimony is not the Foundation’s only task however. It is equally Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland and supported by a grant from Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway through the important to us to increase the public’s knowledge of the history of the Polish Jews who for EEA Financial Mechanism and the Norwegian Financial Mechanism. centuries contributed to Poland’s heritage. Our most important educational activities include the “To Bring Memory Back” program, addressed to high school students, and POLIN – Polish Jews’ Heritage www.polin.org.pl – a multimedia web portal that will present the history of 1200 Jewish communities throughout Poland. -

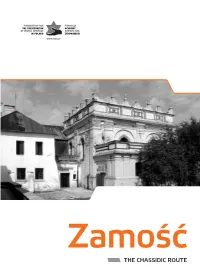

Chassidic-Route.Pdf

Zamość THE CHASSIDIC ROUTE 02 | Zamość | introduction | 03 Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland was established in March ���� by the Dear Sirs, Union of Jewish Communities in Poland and the World Jewish Restitution Organization (WJRO). �is publication is dedicated to the history of the Jewish community of Zamość and is a part Our mission is to protect and commemorate the surviving monuments of Jewish cultural of a series of pamphlets presenting history of Jews in the localities participating in the Chassidic heritage in Poland. �e priority of our Foundation is the protection of the Jewish cemeteries: in Route project, run by the Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland since ����. cooperation with other organizations and private donors we saved from destruction, fenced and �e Chassidic Route is a tourist route which follows the traces of Jews from southeastern Poland commemorated several of them (e.g. in Zakopane, Kozienice, Mszczonów, Kłodzko, Iwaniska, and, soon, from western Ukraine. �� communities, which have already joined the project and where Strzegowo, Dubienka, Kolno, Iłża, Wysokie Mazowieckie). �e actions of our Foundation cover the priceless traces of the centuries-old Jewish presence have survived, are: Baligród, Biłgoraj, also the revitalization of particularly important and valuable landmarks of Jewish heritage, e.g. the Chełm, Cieszanów, Dębica, Dynów, Jarosław, Kraśnik, Lesko, Leżajsk (Lizhensk), Lublin, Przemyśl, synagogues in Zamość, Rymanów and Kraśnik. Ropczyce, Rymanów, Sanok, Tarnobrzeg, Ustrzyki Dolne, Wielkie Oczy, Włodawa and Zamość. We do not limit our heritage preservation activities only to the protection of objects. It is equally �e Chassidic Route runs through picturesque areas of southeastern Poland, like the Roztocze Hills important for us to broaden the public’s knowledge about the history of Jews who for centuries and the Bieszczady Mountains, and joins localities, where one can find imposing synagogues and contributed to cultural heritage of Poland. -

WORLD HERITAGE No. 84

UNESCO PUBLISHING WORLD HERITAGE No. 84 his year, the World Heritage Committee will meet for its 41st session in the editorial World Heritage site of the Historic Centre of Kraków. We are very pleased to be Thosted by Poland, an early supporter of the World Heritage Convention whose experts even participated in the drafting of the Convention itself. Poland’s heritage sites represent many aspects of World Heritage: a diversity of values, a rich history, and transboundary cooperation, among others. In this issue, we will discover an overview of the architectural landscape of Poland, as well as the evolution of the protection of heritage in the country, from the early interest in preserving heritage to the rise of the community movement for protecting sites in the 19th century, and involvement of Polish experts in various international efforts such the drafting of the Venice Charter, and the formation of ICOMOS and of Cover: XXXXXXXXXXXX the International Committee of the Blue Shield (ICBS). Poland is a leading authority on issues related to reconstruction, due in part to its experience in Warsaw: during the Second World War, more than 85 per cent of the city’s historic centre was destroyed, and following a five-year campaign led by citizens after the war, painstaking efforts resulted in the exemplary reconstruction of its churches, palaces and marketplace. The Archive of the Warsaw Reconstruction Office, which contains documents on the destruction of Warsaw during the war and its subsequent rebuilding, is now listed in the UNESCO’s International Register of the Memory of the World Programme. -

Reception of Città Ideale. Italian Renaissance Cultural Impact Upon Town Planning in Poland

The 18th International Planning History Society Conference - Yokohama, July 2018 Reception of Città Ideale. Italian Renaissance cultural impact upon town planning in Poland Maciej Motak * Maciej Motak, PhD, DSc, Faculty of Architecture, Cracow University of Technology, [email protected] The concept of the Ideal City, as developed in Italy during the 15th and 16th centuries, has produced a significant number of treatises with texts and drawings, which, largely speaking, are theoretical rather than applied. Although new Renaissance towns were quite a rare phenomenon both in Italy and in other countries, a number of such towns were constructed in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Two types of new towns were built according to their basic functions: the town-and-residence compounds were prestigious family seats combined with adjacent towns, while the “economic” towns were local trading centres. The fashionable ideas and forms of the Città Ideale were adopted by those towns’ founders and planners. Selected examples of Polish Renaissance towns are discussed in this paper. Apart from Zamosc (1578, designed by Bernardo Morando and often considered the most perfect Ideal City, and not only in Poland), other slightly less ideal though equally interesting town- and-residence compounds are also described: Zolkiew (1584, now Zhovkva, Ukraine) and Stanislawow (1662, now Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine). Three of the “economic” towns are also presented here: Glowow (1570, now Glogow Malopolski), Rawicz (1638) and Frampol (founded as late as c. 1717, although still of a purely Renaissance form). Keywords: ideal cities, Renaissance planning, Polish town planning, urban composition, cross- cultural exchange Introduction The well-established term Ideal City is primarily associated with the Renaissance1, principally the Italian Renaissance since it was developed in the 15th and 16th centuries mostly in Italy (and to a lesser degree in France and Germany2).