Title: Marcus Antonius in the Space of "Oblivion" Or About the Representation of the Temple on the Denarius RRC 496/1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

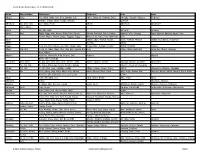

Name Date of Death Date of Paper Place of Burial

Name Date of Death Date of Paper Place of Burial Haack, Charles A. Graves 30 Nov 1907 Belvidere Cemetery Haack, Charles R. 12 Mar 1922 Haack, Edward J. 18 Nov 1938 Belvidere Haack, John 29 May 1924 Belvidere Cemetery Haack, Maria Johana Martens 23 May 1921; pg. 6 Belvidere Cemetery Haack, Theodore C. 26 Aug 1912 Belvidere Cemetery Haacker, Mrs. Anna 8 Sep 1938 Union Cemetery Haafe, William 21 Nov 1928 Kenosha, WI Haag, Jacob 20 Feb 1940 Belvidere Cemetery Haas, Edna A. 23 Sep 1981 Haas, Nancy J. 1 Jan 1996 Shirland Cemetery Haase, Dorothy D. 3 Nov 1987 Marengo City Cemetery Haase, Henry 10 Jan 1896 Haase, Nellie 10 Apr 1981 Sunset Memorial Gardens Haase, William (See: Haafe, William) Haatz, Olga 25 Jun 1930 Cherry Valley Hadebank, Ernest 6 Oct 1941 Habedank, Hanna 8 Oct 1918 15 Oct 1918 Belvidere Cemetery Habedank, Richard 23 Mar 1930 Belvidere Cemetery Habedank, Sophie 13 Jul 1942 14 Jul 1942 Habedonk, H. G. 5 Jul 1900 Indiana Haber, Joyce M. 11 Nov 2000 Dubuque, IA Haberdank, Johanna 8 Jan 1906 Belvidere Cemetery Habina, Anthony C. 22 May 1995 Hable, Edward L. 12 Sep 1988 20 Sep 1988 Sun City West, AZ Hable, Joseph A. 28 Dec 1991 Pittsville, WI Hable, Leonard F. 30 Sep 2007 St. Mary’s Cemetery Hable, Opal E. 16 Jul 1995 Hachmann, Alice M. 23 Dec 2012 RR Star 25, 26 Dec 2012 Dubuque, IA Hack, Earl R. 14 Jul 1990 Lasalle, IL Hack, baby of George 20 Jan 1903 Chicago Hackenback, Henry 29 Mar 1936 Chicago Hacker, John 7 May 1933 Marengo Cemetery Hacker, Werner H. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

Historical Background Notes

William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra Historical Mr. Pogreba Background Helena High School The Roman World in 41 B.C.E. The Roman Republic ❖ The Roman Republic was founded in 509 B.C.E and ended in 27 B.C.E., replaced by the Roman Empire ❖ By 41 B.C.E. the Roman Republic controlled most of the Mediterranean and modern France. ❖ It was ruled by the Senate. Roman General and Politician Julius Caesar • Born to a middle class family in 100 B.C.E. • The greatest general in the history of Rome, he conquered modern France and put Egypt under Roman control. • He was appointed dictator for life in 44 B.C.E. • When he aspired to become King/ Emperor, he was murdered by the Senate on March 15, 44 B.C.E. Aftermath of Caesar’s Death ❖ His friend, Mark Antony, gave a speech over Caesar’s body that made the mob run wild in Rome, causing the assassins to flee. ❖ Eventually, the Roman territories are divided between three rulers in the Triumvirate, who divide the Roman territories between them. The Second Triumvirate ❖ The Roman territories were ruled by three men: ❖ Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony) ❖ Octavian Caesar ❖ Marcus Lepidus ❖ They were threatened by the Parthian Empire and Sextus Pompey Octavian Lepidus Marc Antony 37 B.C.E. Territories of the Second Triumvirate Triumvir of Rome Marc Antony • Born in 83 B.C.E. • General under the command of Julius Caesar, he led the war against those who had killed Caesar. • He was the senior partner of the Trimuvirate, and given the largest territory to control in the East. -

Tragic Downfall of Antony in Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra

Bilecik Şeyh Edebali Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Makale Geliş (Submitted) Bilecik Şeyh Edebali University Journal of Social Sciences Institute Makale Kabul (Accepted) 24.08.2019 DOİ: 10.33905/bseusbed.610180 05.12.2019 Tragic Downfall of Antony in Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra Abdullah KODAL1 Abstract Although there have been lots of debates about the reason of downfall of the great Roman general Antony, there is exactly one forefront reason in his destruction, it is Cleopatra herself. Her subversive power over Antony together with her manipulative and seductive power leads to the gradual breakdown of the male protagonist Antony and his destruction at the end. Thus, to understand all aspects of his downfall as one of the triumvirs of the great Roman Empire, we have to know exactly, who Cleopatra is and the role she played in Antony’s downfall as a woman. Shakespeare’s Cleopatra even today regarded by some as the source of beauty and by some as the source of manipulation but the common point for most people; it would not be possible to describe her within the limited definitions of woman in patriarchal society and one would need more than these, at least, for Cleopatra. Regarding the different approaches and criticisms about the downfall of the protagonist Antony, my aim in this article is to show how Cleopatra as an outstanding female model in ancient ages led to the downfall of the male protagonist of Shakespeare’s play the great Roman general Antony by using her special feminine characteristic features such as her beauty, her tempting words and speeches and also her seductive wiles against patriarchal assumptions that leads her to being condemned as a femme fatale. -

Assemblées Des États Membres De L'ompi Assemblies of the Member

A/59/INF/7 ORIGINAL : FRANÇAIS / ENGLISH DATE : 13 DÉCEMBRE 2019 /DECEMBER 13, 2019 Assemblées des États membres de l’OMPI Cinquante-neuvième série de réunions Genève, 30 septembre – 9 octobre 2019 Assemblies of the Member States of WIPO Fifty-Ninth Series of Meetings Geneva, September 30 to October 9, 2019 LISTE DES PARTICIPANTS LIST OF PARTICIPANTS établie par le Secrétariat prepared by the Secretariat A/59/INF/7 page 2 I. ÉTATS/STATES (dans l’ordre alphabétique des noms français des États) (in the alphabetical order of the names in French) AFGHANISTAN Nasir Ahmad ANDISHA (Mr.), Ambassador, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission, Geneva Shoaib TIMORY (Mr.), Minister-Counsellor, Permanent Mission, Geneva [email protected] Soman FAHIM (Ms.), Second Secretary, Permanent Mission, Geneva AFRIQUE DU SUD/SOUTH AFRICA Nozipho Joyce MXAKATO-DISEKO (Ms.), Ambassador, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission, Geneva Rory VOLLER (Mr.), Commissioner, Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC), Department of Trade and Industry, Pretoria Evelyn MASOTJA (Ms.), Deputy Director-General, Consumer and Corporate Regulation Division, Department of Trade and Industry, Pretoria Meshendri PADAYACHY (Ms.), Manager, Intellectual Property Law and Policy, Consumer and Corporate Regulation Division, Department of Trade and Industry, Pretoria [email protected] Sizeka MABUNDA (Mr.), Deputy Director, Audio-Visual, Department of Arts and Culture, Pretoria [email protected] Nomonde MAIMELA (Ms.), Executive Manager, Companies and Intellectual -

A Comparison of the Two Principal Characters of Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra with Their Prototypes in Plutarch's Life of Marcus Antonius Robert G

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1949 A Comparison of the Two Principal Characters of Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra with Their Prototypes in Plutarch's Life of Marcus Antonius Robert G. Lynch Loyola University Chicago Recommended Citation Lynch, Robert G., "A Comparison of the Two Principal Characters of Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra with Their rP ototypes in Plutarch's Life of Marcus Antonius" (1949). Master's Theses. Paper 772. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/772 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1949 Robert G. Lynch A CON;PARISON OF THE T"<'IO PRIiWIPAL CHARACTERS OF SHAKESP:2:J.RE' S ANTONY -AND CLEOPATRA laTH THEla PROTOTYl?ES IN PLUTARCH t S ~ OF r4ARCUS ANTONIUS BY ROBERT G. LYNCH, S.J. A 'fHESIS SUBI\~ITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIRl:l:;j\IENTS FOIt THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LOYOLA UNIVERSITY 1949 ~ ------------------------------------------------------------~ TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. Illll'RODUCTION •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •• 1 The subject---state of question-- comparison of Shakespee.re and Plutarch ---Shakespeare's method of prime in terest---why characterization instead of plot or diction---why this play-- an objection answered---the procedure. II. CLEOPAffRA, COURTESAN OR QUEEN? •••••••••••••••••• 13 Reason for treating Cleopatra first-- importance of Cleopatra for the trag edy---Shakespeare's aims: specific and general---political motives in Plutarch's Queen---real love in Shakes peare's---Prof. -

Aguirre-Santiago-Thesis-2013.Pdf

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE SIC SEMPER TYRANNIS: TYRANNICIDE AND VIOLENCE AS POLITICAL TOOLS IN REPUBLICAN ROME A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in History By Santiago Aguirre May 2013 The thesis of Santiago Aguirre is approved: ________________________ ______________ Thomas W. Devine, Ph.D. Date ________________________ ______________ Patricia Juarez-Dappe, Ph.D. Date ________________________ ______________ Frank L. Vatai, Ph.D, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii DEDICATION For my mother and father, who brought me to this country at the age of three and have provided me with love and guidance ever since. From the bottom of my heart, I want to thank you for all the sacrifices that you have made to help me fulfill my dreams. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I want to thank Dr. Frank L. Vatai. He helped me re-discover my love for Ancient Greek and Roman history, both through the various courses I took with him, and the wonderful opportunity he gave me to T.A. his course on Ancient Greece. The idea to write this thesis paper, after all, was first sparked when I took Dr. Vatai’s course on the Late Roman Republic, since it made me want to go back and re-read Livy. I also want to thank Dr. Patricia Juarez-Dappe, who gave me the opportunity to read the abstract of one of my papers in the Southwestern Social Science Association conference in the spring of 2012, and later invited me to T.A. one of her courses. -

Marcus Junius Brutus David B

History Publications History 2007 Marcus Junius Brutus David B. Hollander Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/history_pubs Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Political History Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ history_pubs/6. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marcus Junius Brutus Abstract Marcus Junius Brutus (BREW-tuhs) came from noble stock. His reputed paternal ancestor, Lucius Junius Brutus, helped overthrow the last king of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, in 510 B.C.E. and then became one of the first two consuls of the Roman Republic. His mother, Servilia Caepionis, was descended from Gaius Servilius Ahala, who had murdered the would-be tyrant Spurius Maelius in 439. Disciplines Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity | Political History Comments "Marcus Junius Brutus," in Great Lives from History: Notorious Lives, ed. Carl L. Bankston III, Salem Press (2007) 146-148. Used with permission of EBSCO Information Services, Ipswich, MA. This article is available at Iowa State University Digital Repository: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/history_pubs/6 Great Lives from History: Notorious Lives Marcus Junius Brutus by David B. -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Aby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Abigeal, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby, Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ad, Ade, Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann, Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Senga, Taggett, Taggy Nancy, Una, Unity, Uny, Winifred Una Aidan Aedan, Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus, Maodhog Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily, Ellie, Helen, Lena, Nel, Nellie, Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Alb, Albt A, Ab, Al, Albie, Albin, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird,Elvis Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Burt, Elbert Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Andi, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alsander, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Ec, Eleck, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra, Zander Alusdar, Alusdrann, Saunder Alfred Alf, Alfd Al, Alf, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alberedus, Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Alc Ailse, Aisley, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Allison, Alicia, Alyssa, Eileen, Ellen Ailis, Ailise, Aislinn, Alis, Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Aleysia, Alicia, Alitia Ally, -

A Lesson for Cicero De Oratore 3,12.45: Laelia

Anne Leen, Professor of Classics Furman University September 2008 Lesson Plan for Cicero, De Oratore 3.12.45 Laelia's Latin Pronunciation I. Introduction Cicero's De Oratore is a treatise on rhetoric in dialogue form written in 55 BCE. The principal speakers are the orators Lucius Licinius Crassus (140-91 BCE) and Marcus Antonius (143-87 BCE), the grandfather of the Triumvir. The dramatic date of the dialogue is September 91 BCE. The setting is the Tusculan villa of Antonius. While the work as a whole addresses the ideal orator, Book 3 is devoted largely to good style, the first requirement of which is pure and correct Latin. The topic at hand in this passage is pronunciation, defined as a matter of regulating the tongue, breath, and tone of voice (lingua et spiritus et vocis sonus, 3.11.40). The speaker, Crassus, has noticed the recent affectation of rustic pronunciation in people who desire to evoke the sounds of what they wrongly think of as the purer diction of the past, and correspondingly the values of antiquity. To Crassus this is misguided and ill-informed. The urban Roman sound that must be emulated lacks rustification and instead mirrors ancient Roman diction, the only remaining traces of which he finds in the speech of his mother-in-law, Laelia, as he explains. II. Marcus Tullius Cicero, De Oratore 3.12.45 Equidem cum audio socrum meam Laeliam - facilius enim mulieres incorruptam antiquitatem conservant, quod multorum sermonis expertes ea tenent semper, quae prima didicerunt - sed eam sic audio, ut Plautum mihi aut Naevium videar audire, sono ipso vocis ita recto et simplici est, ut nihil ostentationis aut imitationis adferre videatur; ex quo sic locutum esse eius patrem iudico, sic maiores; non aspere ut ille, quem dixi, non vaste, non rustice, non hiulce, sed presse et aequabiliter et leniter. -

Julius Caesar

Working Paper CEsA CSG 168/2018 ANCIENT ROMAN POLITICS – JULIUS CAESAR Maria SOUSA GALITO Abstract Julius Caesar (JC) survived two civil wars: first, leaded by Cornelius Sulla and Gaius Marius; and second by himself and Pompeius Magnus. Until he was stabbed to death, at a senate session, in the Ides of March of 44 BC. JC has always been loved or hated, since he was alive and throughout History. He was a war hero, as many others. He was a patrician, among many. He was a roman Dictator, but not the only one. So what did he do exactly to get all this attention? Why did he stand out so much from the crowd? What did he represent? JC was a front-runner of his time, not a modern leader of the XXI century; and there are things not accepted today that were considered courageous or even extraordinary achievements back then. This text tries to explain why it’s important to focus on the man; on his life achievements before becoming the most powerful man in Rome; and why he stood out from every other man. Keywords Caesar, Politics, Military, Religion, Assassination. Sumário Júlio César (JC) sobreviveu a duas guerras civis: primeiro, lideradas por Cornélio Sula e Caio Mário; e depois por ele e Pompeius Magnus. Até ser esfaqueado numa sessão do senado nos Idos de Março de 44 AC. JC foi sempre amado ou odiado, quando ainda era vivo e ao longo da História. Ele foi um herói de guerra, como outros. Ele era um patrício, entre muitos. Ele foi um ditador romano, mas não o único. -

The Roman World • Lecture 6 • the End of the Republic: Julius Caesar

• MDS1TRW: The Roman World • Lecture 6 • The End of the Republic: Julius Caesar CRICOS Provider 00115M latrobe.edu.au CRICOS Provider 00115M The end of the Republic: 133-27 BCE 1. Poli=cal and civil conflict of late Republic 2. Julius Caesar http://www.clas.ufl.edu/users/jmarks/Caesar/Caesar.html 133 BCE • AEalus III of PerGamum • Tiberius Gracchus = Tribune of the People (plebs) • veto power • T. Gracchus’ Land Bill http://sightseeingrome.blogspot.com.au/2010/10/portrait-of-gracchi-according-to.html 123 BCE • Gaius Gracchus = Tribune of the People (plebs) – Grain price – Extor=on Courts • equites – Ci=zenship Bill http://sightseeingrome.blogspot.com.au/2010/10/portrait-of-gracchi-according-to.html Op=mates and Populares • Op=mates: senatorial • Populares: people • Lucius Cornelius Sulla http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sulla_Glyptothek_Munich_309_white_bkg.jpg • Gaius Marius http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaius_Marius GAIUS MARIUS • 105: Gauls • Army reform • Consul 107, 104-100, 86 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaius_Marius Rome vs. ItalY • Ci=zenship Bill • 91 Drusus murdered • 91-88 Social War • vs. socii http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_image.aspx?image=ps297454.jpg&retpage=17508 Rome vs. Pontus • Mithridates VI • Sulla… • Sulpicius: Marius Sulla vs. Marius • Proscrip=ons • Cinna consul 87 • Cinna & Marius 86 • Sulla dictator 82 • New cons=tu=on 81 Sulla dictator • New cons=tu=on 81 – Tribunes of the People lose veto – Council of People lose leGislave riGhts – doubles Senate – Extor=on court -> senate –