Tragic Downfall of Antony in Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

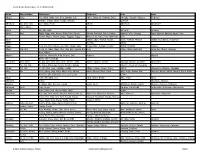

Name Date of Death Date of Paper Place of Burial

Name Date of Death Date of Paper Place of Burial Haack, Charles A. Graves 30 Nov 1907 Belvidere Cemetery Haack, Charles R. 12 Mar 1922 Haack, Edward J. 18 Nov 1938 Belvidere Haack, John 29 May 1924 Belvidere Cemetery Haack, Maria Johana Martens 23 May 1921; pg. 6 Belvidere Cemetery Haack, Theodore C. 26 Aug 1912 Belvidere Cemetery Haacker, Mrs. Anna 8 Sep 1938 Union Cemetery Haafe, William 21 Nov 1928 Kenosha, WI Haag, Jacob 20 Feb 1940 Belvidere Cemetery Haas, Edna A. 23 Sep 1981 Haas, Nancy J. 1 Jan 1996 Shirland Cemetery Haase, Dorothy D. 3 Nov 1987 Marengo City Cemetery Haase, Henry 10 Jan 1896 Haase, Nellie 10 Apr 1981 Sunset Memorial Gardens Haase, William (See: Haafe, William) Haatz, Olga 25 Jun 1930 Cherry Valley Hadebank, Ernest 6 Oct 1941 Habedank, Hanna 8 Oct 1918 15 Oct 1918 Belvidere Cemetery Habedank, Richard 23 Mar 1930 Belvidere Cemetery Habedank, Sophie 13 Jul 1942 14 Jul 1942 Habedonk, H. G. 5 Jul 1900 Indiana Haber, Joyce M. 11 Nov 2000 Dubuque, IA Haberdank, Johanna 8 Jan 1906 Belvidere Cemetery Habina, Anthony C. 22 May 1995 Hable, Edward L. 12 Sep 1988 20 Sep 1988 Sun City West, AZ Hable, Joseph A. 28 Dec 1991 Pittsville, WI Hable, Leonard F. 30 Sep 2007 St. Mary’s Cemetery Hable, Opal E. 16 Jul 1995 Hachmann, Alice M. 23 Dec 2012 RR Star 25, 26 Dec 2012 Dubuque, IA Hack, Earl R. 14 Jul 1990 Lasalle, IL Hack, baby of George 20 Jan 1903 Chicago Hackenback, Henry 29 Mar 1936 Chicago Hacker, John 7 May 1933 Marengo Cemetery Hacker, Werner H. -

CMF Fraternity English 2020.Indd

Claretian Fraternity News Bulletin for Families and Associates, Province of Bangalore, Vol. 10, 2020 May the Joy and Peace of Christmas be with you all through the New Year. Wishing you a season of blessings from God. Merry Christmasand Prosp erous New Year2021 MESSAGE FROM THE DELEGATE SUPERIOR n 24th October 2020 we celebrated the 150th death The year 2020 is also remarkable O anniversary of our Founder St. Antony Mary Claret. for the Indian Claretians in a very Eighty years after his death Pope Pius XII proclaimed him a special way as our Congregation saint in 1950, formally recognizing that he heroically practiced is completing fi fty years of its the Christian virtues and presenting him to the universal existence and ministry in our Church as an example to follow. Fr. Claret founded religious Country. It was in 1970 that the Congregations of men and women, whose members are fi rst Claretian community was now at the service of the Word of God in over sixty countries. established in a small village in These missionaries give testimony to the Gospel values in Kerala called Kuravilangad, and the past fi fty years have brought different ways, namely through direct preaching of the Word to us immeasurable divine blessings. The small community of God, social and charitable activities in favour of the poor, started with three priests, fi ve novices and a small batch of educational ministry, pastoral service in the local Churches minor seminarians have grown today to a community of over etc. The life of St. Claret has motivated so many young men 550 priests and a good number of seminarians at different that the Claretian Congregation has given to the Church nearly stages of their formation, grouped under fi ve Major Organisms, three hundred martyrs, consisting of priests, lay brothers and namely three full-fl edged Provinces and two independent seminarians, during the Spanish civil war. -

Assemblées Des États Membres De L'ompi Assemblies of the Member

A/59/INF/7 ORIGINAL : FRANÇAIS / ENGLISH DATE : 13 DÉCEMBRE 2019 /DECEMBER 13, 2019 Assemblées des États membres de l’OMPI Cinquante-neuvième série de réunions Genève, 30 septembre – 9 octobre 2019 Assemblies of the Member States of WIPO Fifty-Ninth Series of Meetings Geneva, September 30 to October 9, 2019 LISTE DES PARTICIPANTS LIST OF PARTICIPANTS établie par le Secrétariat prepared by the Secretariat A/59/INF/7 page 2 I. ÉTATS/STATES (dans l’ordre alphabétique des noms français des États) (in the alphabetical order of the names in French) AFGHANISTAN Nasir Ahmad ANDISHA (Mr.), Ambassador, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission, Geneva Shoaib TIMORY (Mr.), Minister-Counsellor, Permanent Mission, Geneva [email protected] Soman FAHIM (Ms.), Second Secretary, Permanent Mission, Geneva AFRIQUE DU SUD/SOUTH AFRICA Nozipho Joyce MXAKATO-DISEKO (Ms.), Ambassador, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission, Geneva Rory VOLLER (Mr.), Commissioner, Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC), Department of Trade and Industry, Pretoria Evelyn MASOTJA (Ms.), Deputy Director-General, Consumer and Corporate Regulation Division, Department of Trade and Industry, Pretoria Meshendri PADAYACHY (Ms.), Manager, Intellectual Property Law and Policy, Consumer and Corporate Regulation Division, Department of Trade and Industry, Pretoria [email protected] Sizeka MABUNDA (Mr.), Deputy Director, Audio-Visual, Department of Arts and Culture, Pretoria [email protected] Nomonde MAIMELA (Ms.), Executive Manager, Companies and Intellectual -

State of Delaware

State of Delaware Department of Elections Permanent Absentee Voter List Voter Information First Name Middle Name Last Name County GARY LEE BENSINGER SUSSEX EDNA AARON KENT JOHN A AARON NEW CASTLE THOMAS A AARON KENT VERA JEAN AARON NEW CASTLE HOWARD LEONARD ABARE SUSSEX SALLY A ABARE SUSSEX PETER ROBERT ABATE KENT JESSICA LEIGH ABBEY NEW CASTLE BARBARA R ABBOTT SUSSEX BRUCE ALLEN ABBOTT NEW CASTLE CAROL E ABBOTT KENT ELIZABETH CARRIE ABBOTT KENT JANICE M ABBOTT KENT JO ANN ABBOTT KENT JOHN S ABBOTT SUSSEX JUDITH ANN ABBOTT KENT KARLA W ABBOTT SUSSEX SHARON L ABBOTT SUSSEX KAREN M ABDALA SUSSEX KHADIRA NAEEMA ABDUL-AZIZ KENT KHALIL ABDUL-MAJID NEW CASTLE AHMAD J ABDULLAH NEW CASTLE ALMESHIA ZAHIR ABDULLAH NEW CASTLE MICAH YUSEF ABDULLAH NEW CASTLE YASMEEN ABDULLAH NEW CASTLE ARTHUR ELVAN ABEL SUSSEX DIANE CLAIRE ABEL KENT GERTRUDE E ABEL NEW CASTLE JOANNE ABEL NEW CASTLE JOSEPH MILBURN ABELL SUSSEX SALLIE HEINRICHS ABELL SUSSEX NAWAL A ABOU-RAHME NEW CASTLE RAJA W ABOU-RAHME NEW CASTLE DOROTHY MARIE ABRAHAM KENT LISA SIEGEL ABRAHAMSON SUSSEX CHRISTINA ABRAMOWICZ SUSSEX CAITLIN NICOLE ABRAMS SUSSEX DOROTHY E ABRAMS NEW CASTLE MARILYN NASHMAN ABRAMS NEW CASTLE NOELLY RAPHAELLI ABREU NEW CASTLE IRA L ABSHER SUSSEX JAY L ABSHER SUSSEX LINDA K ABSHER SUSSEX SHIRLEY A ABSHER SUSSEX TREVA GAIL ABSHER SUSSEX HANAA M ABUELELA NEW CASTLE ELIZABETH MILIANA ABUSCHINOW SUSSEX SANDSHA ABUSCHINOW SUSSEX GWEN MARY ACCARDI KENT CLAUDIA E ACERO LUNA NEW CASTLE HELEN M ACHENBACH NEW CASTLE DOLORES ACKER SUSSEX EDWIN JOHN ACKER NEW CASTLE LEWIS D ACKER SUSSEX -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Aby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Abigeal, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby, Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ad, Ade, Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann, Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Senga, Taggett, Taggy Nancy, Una, Unity, Uny, Winifred Una Aidan Aedan, Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus, Maodhog Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily, Ellie, Helen, Lena, Nel, Nellie, Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Alb, Albt A, Ab, Al, Albie, Albin, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird,Elvis Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Burt, Elbert Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Andi, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alsander, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Ec, Eleck, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra, Zander Alusdar, Alusdrann, Saunder Alfred Alf, Alfd Al, Alf, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alberedus, Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Alc Ailse, Aisley, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Allison, Alicia, Alyssa, Eileen, Ellen Ailis, Ailise, Aislinn, Alis, Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Aleysia, Alicia, Alitia Ally, -

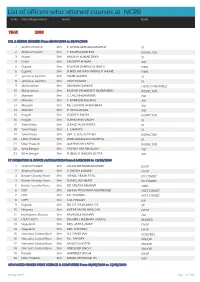

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

Clodia, Fulvia, Livia, Messalina: What Can We Really Learn About the Elite Women of Rome?

Clodia, Fulvia, Livia, Messalina: what can we really learn about the elite women of Rome? ‘A dissertation submitted to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts’ 29001652 Jacqueline Margaret Meredith 2014 Master’s Degrees by Examination and Dissertation Declaration Form. 1. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Name: J M Meredith Date: 21 March 2014 2. This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Name: J M Meredith Date: 21 March 2014 3. This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Name: J M Meredith Date: 21 March 2014 4. I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying, inter-library loan, and for deposit in the University’s digital repository. Name: J M Meredith Date: 21 March 2014 Supervisor’s Declaration. I am satisfied that this work is the result of the student’s own efforts. Name: …………………………………………………………………………... Date: ……………………………………………………………………………... Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................... 5 Introduction and literature review ........................................................... 6 Women in the Late Republic ................................................................. -

Table 5: Full List of First Forenames Given, Scotland, 2014 (Final) in Rank Order

Table 5: Full list of first forenames given, Scotland, 2014 (final) in rank order NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died. Number of Number of Rank1 Boys' names NB Rank1 Girls' names NB babies babies 1 Jack 583 * 1 Emily 569 * 2 James 466 * 2 Sophie 542 * 3 Lewis 411 * 3 Olivia 485 * 4 Oliver 403 * 4 Isla 435 5 Logan 354 * 5 Jessica 419 * 6 Daniel 349 * 6 Ava 379 7 Noah 321 * 7 Amelia 372 * 8 Charlie 320 * 8 Lucy 363 * 9 Lucas 310 * 9 Lily 310 * 10 Alexander 309 * 10 Ellie 278 * 11 Mason 285 * 11 Ella 273 12 Harris 276 * 12 Sophia 271 13 Max 274 * 13 Grace 265 * 14 Harry 268 * 14 Chloe 251 15 Finlay 267 15 Freya 249 16 Adam 266 * 16 Millie 246 17 Aaron 264 * 17 Mia 230 18 Ethan 259 18 Emma 229 19= Cameron 256 19 Eilidh 224 19= Jacob 256 * 20 Anna 218 21 Callum 252 21 Charlotte 213 * 22 Archie 239 22 Eva 210 * 23 Alfie 236 * 23= Holly 208 24 Leo 234 * 23= Ruby 208 * 25 Thomas 228 * 25 Layla 190 26 Nathan 226 26 Hannah 187 27 Riley 223 * 27 Evie 175 28 Rory 215 28 Orla 171 * 29 Matthew 214 29 Katie 170 * 30 Joshua 213 * 30 Poppy 162 * 31 Oscar 212 31 Erin 154 32 Jamie 211 32 Leah 144 33 Ryan 208 * 33 Lexi 140 * 34 Luke 195 34 Molly 132 35 William 180 * 35= Isabella 130 36 Liam 178 35= Skye 130 37 Dylan 176 * 37 Lacey 124 * 38 Samuel 166 38 Abigail 122 * 39 Andrew 163 * 39 Georgia 119 40= David 154 * 40= Rebecca 115 40= John 154 40= Sofia 115 42 Connor 146 42= Amber 113 * 43= Brodie 144 42= Hollie 113 43= Kyle 144 * 44 Amy 111 45 Joseph 143 45= Brooke 107 46 Kian 142 * 45= Daisy 107 47 Benjamin 141 45= Niamh 107 48= Aiden 139 48= Lilly 106 48= Harrison 139 * 48= Zoe 106 * 50 Robert 135 * 50 Rosie 102 51= Ben 130 51 Abbie 101 51= Muhammad 130 52 Robyn 100 * 53 Michael 127 53 Sienna 98 54 Tyler 123 * 54= Summer 96 55 Kai 120 54= Zara 96 56 Euan 114 * 56 Iona 91 57= Arran 112 57 Maya 89 57= Jayden 112 58 Sarah 88 59 Jake 111 * 59= Aria 87 60= Cole 110 59= Maisie 87 60= Ollie 110 * 61 Cara 85 Footnote 1) The equals sign indicates that there is more than one name with this position of rank in the list. -

Sovereignty and Colonialism in Nineteenth-Century International Law 1 Antony Anghie∗

4 Harvard International Law Journal / Vol. 40 19999 / Sovereignty and Colonialism in International Law 3 Volume 40, Number 1, Winter 1999 Finding the Peripheries: Sovereignty and Colonialism in Nineteenth-Century International Law 1 Antony Anghie∗ I. INTRODUCTION International law is universal. It is a body of law that applies to all states regardless of their specific cultures, belief systems, and political organizations. It is a common set of doctrines that all states use to regulate relations with each other. The association between international law and universality is so ingrained that pointing to this connection appears tautological. And yet, the universality of international law is a relatively recent development. It was not until the end of the nineteenth century that a set of doctrines was established as applicable to all states, whether these were in Asia, Africa, or Europe. The universalization of international law was principally a consequence of the imperial expansion that took place towards the end of the \long nineteenth century."2 The conquest of non-European3 peoples for economic and political 1* Associate Professor of Law, University of Utah College of Law. S.J.D., Harvard Law School, 1995; LL.B., Monash University, 1987; B.A., Monash University, 1986. My thanks are due to Nathaniel Berman, Robert Chu, Mitchel Lasser, Vasuki Nesiah, Kunal Parker, Ileana Porras, Annelise Riles, Uta Roth, Michael Schwalb, and Lee Teitelbaum; to the Summer Stipend Program of the College of Law, University of Utah, the participants at the Dighton Writers Workshop, and my colleagues at the College of Law at the University of Utah who offered encouragement and comment when this work was presented to the Faculty; and to B.S. -

Bride Surname Bride First Name Bridegroom Surname Bridegroom First Name Date of Marriage (Berger) Sutter Cath. Kutz Hermann 5 Oc

St. Louis County Library History Genealogy Dept. Index to By name of bride [email protected] | 314-994-3300 ext. 2070 St. Liborius marriages, 1856-1895 Date of Bride Surname Bride First Name Bridegroom Surname Bridegroom First Name Marriage (Berger) Sutter Cath. Kutz Hermann 5 Oct 1893 (Kluempers) Borchers Magdalena Schmidt Franziscus 2 May 1893 Abel Catharina Riesenbeck Hermann 21 Nov 1876 Adam Dorothea Kastien Friedr. 8 Aug 1876 Adel Louisa Bange Josephus 19 Oct 1871 Aggenhwert Catharina Stohlamnn Ernst 20 Jan 1885 Albers Bertha Vetter Lorenz 4 Oct 1888 Albitz Emma Maderer Ignaz 17 Feb 1885 Allers Maria Gesina Kleinegger Franciscus Johannes 19 May 1859 Altebockwinkel Gertrudis Huhmann Wilhelmus 17 Oct 1857 Altemeier Louisa Fischer Otto 15 Jan 1873 Altemeier Anna Läger Johannes Gerhard. 31 Oct 1866 Altengreve Catharina Bothe Georgius 18 Apr 1871 Applebaum Francisca Guenther Carl 15 May 1884 Applebaum Maria Kussmann Friedrich 10 May 1883 Applebaum Clara Wigge Georg 15 May 1888 Aselage Maria Hoormann Hermannus 21 Jun 1859 Atzot Gertrudis Hei Martinus 5 Sept 1858 Austermann Maria Peitz Georg 17 Nov 1874 Austermann Theresia Zurline Friedrich 12 Feb 1890 Aut Maria Elisabeth Butterwegge Theodorus 4 Nov 1858 Bain Maria Gertrud Bathe Franz 9 May 1876 Banscher Thecla Abele Joseph 4 Oct 1881 Bartholomae Francisca Schrew Hermann 3 Feb 1874 Bartmeier Elisabeth Flies Casparus 28 Jul 1864 Bartscher Catharina Dickhaus Hermannus 2 Apr 1861 Bauer Margaretha Volmerd Hermann 6 Apr 1891 Baumgartner Amalia Stock Jacob 18 Oct 1894 Beck Maria Ditmeier Georg 8 May 1892 Beck Margaretha Sievers Joseph 22 Nov 1892 1 St. Louis County Library History Genealogy Dept. -

ABSTRACT Asceticism, the Sage, and the Evil Inclination

ABSTRACT Asceticism, the Sage, and the Evil Inclination: Points of Contact between Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity David W. Pendergrass, Ph.D. Mentor: Daniel H. Williams, Ph.D. In Jewish Christian comparative studies there exists a need to explore in more detail the ways in which Jews and Christians interacted religiously and socially in late antiquity. The thesis of this dissertation is that asceticism, the sociological and religious role of the sage, and the anthropological belief in the evil inclination are three aspects shared between predominate groups of Jews and Christians in late antiquity. So far no scholarship has joined these three, inter-dependent areas in Jewish-Christian comparative studies. Chapter Two examines the ways that Jews and Christians did not utterly “part ways” religiously or socially in late antiquity. Evidence of their interaction can be seen in adversus Iudaeos literature, catechetical material, liturgies, biblical exegetical practices, civic and ecclesial legislation, and various archaeological remains. Chapter Three examines the foundations of Christian asceticism and monasticism, especially in Egypt. This chapter critiques the traditional historical reconstructions of monastic origins, with special attention given to the theory that monasticism was an effort by ascetics to become living martyrs. Finally this chapter discusses how the Sayings are a product of the long tradition of ascetic wisdom made especially popular from the fourth through sixth centuries across the Roman Empire. Chapter Four examines the ways Jewish literature speaks to the practice of asceticism. The chapter is divided into three sections: pre-rabbinic Jewish ascetic practices, rabbinic ascetic practices, and the theological and sociological roles of the sage. -

Antony and Cleopatra" Mainly from the Standpoint of Its Three Principal Themes

An Appreciation of "Antony and Cleopatra" Mainly from the Standpoint of Its Three Principal Themes By Mutsuo NAKAMURA Assistant ProfeSsor CゾEnglish・ the FaCtelty of Textit召ε‘勧σ8 and Technology, S乃撚加University (Received September 30,1961) 1 A・1…v・y・dth・c・iti・i・m・・f A・t・ny and・Cl・・p・t・a i・・A Hi・t・・i・a1 St。dy °nthe C・iti・i・m・f Sh・kespea・e’・ん伽ツ・nd C1・・妙・・, there h・v・b・en m・。y approaches to the play, and various interpretations and criticisms have been written ・・it・G・nerally・peaki・g, the criti・i・m・h・w・at・・d…yt・see deeply int・th。 p1。y and recognize its greatness, as time elapsed. But even the most excellent criti- clsms cannot aiways make clear the meaning of the play and be satisfactory, for it comprehends and makes皿uch of only one or a few aspects of the play, which ha・・n・ny aspect・a・if it were a livi・g・rgani・m. Th・p・y・h・1。gical criti。i、m。ften causes us to mistake the fictio1ユal characters of the play-world for real persons in the actual world and to fail to notice the allegorical elements of the characters. The historical criticism often helps us forget what the play means to us in the present age in stressi皿g what it meant to the Elizabethans. The aesthetical criticism ・士ten m・kes・s・ver1・・k that imagery i・・nly th・・aw m・terials・f th・im・gina- ti・n whi・h・・mp・・e・th・p1・y・nd・1・・th・t it・t・a・・1・ti…v・n i・p…e・f・f・reig。 1anguage appeals to the foreigners who do not know the English language and poetry. The multi・conscious criticism often allows us to ignore that the play moves such foreign peoPle as the Japanese audience who have no multi.consciousness