With Cunning Needle Four Centuries of Embroidery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

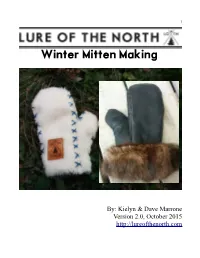

Winter Mitten Making

1 Winter Mitten Making By: Kielyn & Dave Marrone Version 2.0, October 2015 http://lureofthenorth.com 2 Note 1- This booklet is part of a series of DIY booklets published by Lure of the North. For all other publications in this series, please see our website at lureofthenorth.com. Published instructional booklets can be found under "Info Hub" in the main navigation menu. Note 2 – Lure Mitten Making Kits: These instructions are intended to be accompanied by our Mitten Making Kit, which is available through the “Store” section of our website at: http://lureofthenorth.com/shop. Of course, you can also gather all materials yourself and simply use these instructions as a guide, modifying to suit your requirements. Note 3 - Distribution: Feel free to distribute these instructions to anyone you please, with the requirement that this package be distributed in its entirety with no modifications whatsoever. These instructions are also not to be used for any commercial purpose. Thank you! Note 4 – Feedback and Further Help: Feedback is welcomed to improve clarity in future editions. For even more assistance you might consider taking a mitten making workshop with us. These workshops are run throughout Ontario, and include hands-on instructions and all materials. Go to lureofthenorth.com/calendar for an up to date schedule. Our Philosophy: This booklet describes our understanding of a traditional craft – these skills and this knowledge has traditionally been handed down from person to person and now we are attempting to do the same. We are happy to have the opportunity to share this knowledge with you, however, if you use these instructions and find them helpful, please give credit where it is due. -

Machine Embroidery Threads

Machine Embroidery Threads 17.110 Page 1 With all the threads available for machine embroidery, how do you know which one to choose? Consider the thread's size and fiber content as well as color, and for variety and fun, investigate specialty threads from metallic to glow-in-the-dark. Thread Sizes Rayon Rayon was developed as an alternative to Most natural silk. Rayon threads have the soft machine sheen of silk and are available in an embroidery incredible range of colors, usually in size 40 and sewing or 30. Because rayon is made from cellulose, threads are it accepts dyes readily for color brilliance; numbered unfortunately, it is also subject to fading from size with exposure to light or frequent 100 to 12, laundering. Choose rayon for projects with a where elegant appearance is the aim and larger number indicating a smaller thread gentle care is appropriate. Rayon thread is size. Sewing threads used for garment also a good choice for machine construction are usually size 50, while embroidered quilting motifs. embroidery designs are almost always digitized for size 40 thread. This means that Polyester the stitches in most embroidery designs are Polyester fibers are strong and durable. spaced so size 40 thread fills the design Their color range is similar to rayon threads, adequately without gaps or overlapping and they are easily substituted for rayon. threads. Colorfastness and durability make polyester When test-stitching reveals a design with an excellent choice for children's garments stitches so tightly packed it feels stiff, or other items that will be worn hard stitching with a finer size 50 or 60 thread is and/or washed often. -

Thread Yarn and Sew Much More

Thread Yarn and Sew Much More By Marsha Kirsch Supplies: • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Yarn embellishment foot set 920403096 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® 7 hole cord foot with threader 412989945 • HUSQVARNA VIKING ® Clear open toe foot 413031945 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Clear ¼” piecing foot 412927447 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Embroidery Collection # 270 Vintage Postcard • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Sensor Q foot 413192045 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® DESIGNER™ Royal Hoop 360X200 412944501 • INSPIRA® Cut away stabilize 141000802 • INSPIRA® Twin needles 2.0 620104696 • INSPIRA® Watercolor bobbins 413198445 • INSPIRA® 90 needle 620099496 © 2014 KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. VIKING, INSPIRA, DESIGNER and DESIGNER DIAMOND ROYALE are trademarks of KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. HUSQVARNA is a trademark of Husqvarna AB. All trademarks used under license by VSM Group AB • Warm and Natural batting • Yarn –color to match • YLI pearl crown cotton (color to match yarn ) • 2 spools of matching Robison Anton 40 wt Rayon thread • Construction thread and bobbin • ½ yard back ground fabric • ½ yard dark fabric for large squares • ¼ yard medium colored fabric for small squares • Basic sewing supplies and 24” ruler and making pen Cut: From background fabric: 14” wide by 21 ½” long From dark fabric: (20) 4 ½’ squares From medium fabric: (40) 2 ½” squares 21” W x 29” L (for backing) From Batting 21” W x 29” L From YLI Pearl Crown Cotton: Cut 2 strands 1 ¾ yds (total 3 ½ yds needed) From yarn: Cut one piece 5 yards © 2014 KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. VIKING, INSPIRA, DESIGNER and DESIGNER DIAMOND ROYALE are trademarks of KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. HUSQVARNA is a trademark of Husqvarna AB. All trademarks used under license by VSM Group AB Directions: 1. -

Our First Two Big-Time Classes

Translate Latest news from Rittenhouse Needlepoint View this email in your browser May 2018 Newsletter In this Issue: 1. Our First Two Big Time Classes 2. News roundup 3. Thread of the Month: Stef Francis 12 Ply Silk 4. Stitch of the Month: Little Wavy 5. Notes on Needlepoint Our First Two Big-Time Classes Why do I say, "Our first two big-time classes?" Well, because this is the first time in the nearly ten years that we have been open that we will be bringing in professional teachers to our store to teach. And boy are we excited! First up is "78 Stitches, 78 Threads" with Ruth Dilts. This wonderful class is a crash-course in all things Rainbow Gallery. You know Rainbow Gallery threads. You've been using them forever. They are those threads that come on cards https://us2.campaign-archive.com/?e=[UNIQID]&u=9b9b7549e5c8f818070e0508c&id=d352853db8[6/26/2018 4:17:38 PM] and are on the ubiquitous spin racks found pretty much wherever needlepoint supplies are sold. True confession here -- I've been in the business for a while now and even I have trouble keeping all the names of their products straight in my mind so I can only imagine what a jumble it must be for people who don't handle them every day. Well, now is your chance to start untangling that confusing web. And best of all with this class you will end up with a permanent reference volume to take home with you so that in the future you need never be confused by the plethora of Rainbow Gallery options ever again. -

Blackwork Embroidery Pattern Generation Using a Parametric Shape Grammar

Blackwork Embroidery Pattern Generation Using a Parametric Shape Grammar April Grow, Michael Mateas, and Noah Wardrip-Fruin Computational Media Department University of California Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, CA 95060 USA [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Design tools with computational algorithms have been aiding artists for many years in 2D and 3D, from of- fering a digital drafting table or canvas to applying im- age filters or other mathematical transformations. How- ever, there are many more non-digital creative tasks that can benefit from computer-aided design. This paper presents an interactive parametric shape grammar for blackwork embroidery pattern generation, whose pat- terns are then implemented (sewn) using an unmodified home embroidery machine. A design tool executes the grammar-guided user input, enumerates expanded pat- tern possibilities, and compiles patterns into an imme- Figure 1: Generated samples by our parametric shape gram- diately sewable file format. The grammar is capable of mar. These demonstrate borders, focal designs (motifs), and generating published embroidery patterns as well as in- two examples of space-filling patterns. finitely possible new patterns, and has future applica- tions in other areas of surface pattern design and crafts. Related Work Introduction ”Embroidery” is a broad term that roughly encompasses any embellishment by thread, or materials held or strung via thread, on nearly any material, most commonly on textiles. In the multi-millennial lifespan of embroidery, while many fundamental stitches remain the same, dozens of styles and approaches have been classified (Leslie 2007). This paper chooses to focus on non-freeform blackwork embroidery, one of the most restrained styles, as a first approach to em- broidery pattern generation. -

VASTRAM: SPLENDID WORLD of INDIAN TEXTILES CURATED by SHELLY JYOTI a Traveling Textile Exhibition of Indian Council of Cultural Relations, New Delhi, India

VASTRAM: SPLENDID WORLD OF INDIAN TEXTILES CURATED BY SHELLY JYOTI A traveling textile exhibition of Indian council of Cultural Relations, New Delhi, India Curator : Shelly Jyo/ OPENING PREVIEW OCTOBER 15, 2015 DATES: UNTIL OCTOBER 2015 VENUE: PROMENANDE GARDEN, MUSCAT, OMAN ‘Textiles were a principal commodity in the trade of t i‘TexGles were a principal commodity in the trade of the pre-industrial age and India’s were in demand from china and Mediterranean. Indian coUons were prized for their fineness in weave, brilliance in colour, rich variety in designs and a dyeing technology which achieved a fastness of colour unrivalled in the world’ ‘Woven cargoes-Indian tex3les in the East’ by John Guy al age and India’s were in demand from china and Mediterranean. Indian cottons were prized for their fineness in weave, brilliance in colour, rich variety in designs and a dyeing technology which achieved a fastness of colour unrivalled in the world’ ‘Woven cargoes-Indian textiles in the East’ A traveling texGle exhibiGon of Indian council of Cultural Relaons, New Delhi, by John Guy India PICTORIAL CARPET Medium: Silk Dimension: 130cm x 79cm Source: Kashmir, India Classificaon: woven, Rug Accession No:7.1/MGC(I)/13 A traveling texGle exhibiGon of Indian council of Cultural Relaons, New Delhi, India PICTORIAL CARPET Medium: Silk Dimension: 130cm x 79cm Source: Kashmir, India Classificaon: woven, Rug Accession No:7.1/MGC(I)/13 Silk hand knoUed carpet depicts the Persian style hunGng scenes all over the field as well as on borders. Lots of human and animal figures in full moGons is the popular paern oaen seen in painGngs during the Mughal period. -

Stitches and Seam Techniques

Stitches and Seam Techniques Seen on Dark Age / Medieval Garments in Various Museum Collections The following notes have been gathered while attempting to learn stitches and construction techniques in use during the Dark Ages / Medieval period. The following is in no way a complete report, but only an indication of some techniques observed on extant Dark Ages / Medieval garments. Hopefully, others who are researching “actual” garments of the period in question will also report on their findings, so that comparisons can be made and a better total understanding achieved. Jennifer Baker –New Varangian Guard – Hodegon Branch – 2009 Contents VIKING AND SAXON STITCHES 1. RUNNING STITCH 2. OVERSEWING 3. HERRINGBONE 4. BLANKET STITCH SEAMS 1. SEAMS 2. BUTTED SEAMS 3. STAND-UP SEAM 4. SEAMS SPREAD OPEN AFTER JOIN IS MADE 5. “LAPPED” FELL SEAM 6. FELL SEAM WORKED ON WRONG SIDE OF GARMENT FINISHES ON RAW EDGES OF SEAMS SEWING ON TABLET WOVEN BRAID HEMS OTHER STITCHES FOUND IN ARCHEOLOGICAL FINDS REFERENCES 1 Stitches and Seam Techniques VIKING AND SAXON STITCHES There are only four basic stitches to master: 1. RUNNING STITCH , 2. OVERSEWING, ALSO KNOWN AS OVERCAST STITCH OR WHIP STITCH 3. HERRINGBONE , ALSO KNOWN AS CATCH STITCH 4. AND BLANKET STITCH. ALSO KNOWN AS BUTTONHOLE STITCH Running stitch is probably the easiest to start with followed by oversewing. With these two stitches you can make clothing. The other two are for decorative edging. These directions are for a right handed person, if you are left handed remember to reverse all directions. 2 Stitches and Seam Techniques RUNNING STITCH A running stitch is done through one or more layers of fabric (but normally two or more), with the needle going down and up, down and up, in an essentially straight line. -

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identification

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace DATS in partnership with the V&A DATS DRESS AND TEXTILE SPECIALISTS 1 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Text copyright © Jeremy Farrell, 2007 Image copyrights as specified in each section. This information pack has been produced to accompany a one-day workshop of the same name held at The Museum of Costume and Textiles, Nottingham on 21st February 2008. The workshop is one of three produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A, funded by the Renaissance Subject Specialist Network Implementation Grant Programme, administered by the MLA. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audiences. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the public. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750 -1950 Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740-1890 Front cover image: Detail of a triangular shawl of white cotton Pusher lace made by William Vickers of Nottingham, 1870. The Pusher machine cannot put in the outline which has to be put in by hand or by embroidering machine. The outline here was put in by hand by a woman in Youlgreave, Derbyshire. (NCM 1912-13 © Nottingham City Museums) 2 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Contents Page 1. List of illustrations 1 2. Introduction 3 3. The main types of hand and machine lace 5 4. -

Cascade 220® Fingering Lattice Sampler Shawl

FW240 Cascade 220® Fingering Lattice Sampler Shawl Designed by Jennifer Weissman © 2017 Cascade Yarns® - All Rights Reserved. Cascade 220® Fingering Lattice Sampler Shawl Designed By Jennifer Weissman Skill Level: Intermediate Size: 64" wide x 32.5" deep Materials: Cascade Yarns® Cascade 220® Fingering 100% Peruvian Highland Wool 50 g (1.75 oz)/ 273 yds (250 m) 4 skeins color #9593 (Ginseng) US 4 (3.5 mm) knitting needles or size to obtain gauge 3 Stitch markers Yarn needle Pins for blocking Gauge: 20 sts x 40 rows = 4" (10 cm) blocked, in Garter Stitch Abbreviations: BO = Bind Off CO = Cast On K = Knit K2tog = Knit 2 sts together (decrease 1) KFB = Knit into the front and then the back of the next st (increase 1) M = Marker P = Purl PM = Place Marker Sl = Slip st purlwise with yarn in front Sl2-K1-P2SSO = Slip 2 sts knitwise, knit 1, then pass the 2 slipped sts over (decrease 2) SM = Slip Marker SSK = Slip 1 st knitwise, slip 1 st purlwise, insert left needle into front loops of the slipped sts and knit them together (decrease 1) St(s) = Stitch(es) WS = Wrong Side YO = Yarn Over (increase 1) Notes: The Lattice Sampler Shawl is an asymmetric triangular shawl featuring bands of lattice lace in a Garter st field. Each of the lace bands is set off from the Garter st background by ridges of double Garter st. The shawl finishes with a wider band of large lattice lace. This shawl begins with 2 sts. Sts are then added at the beginning of RS rows so that the piece grows into a right triangle. -

'Sublime Stitches' Aida Page 5 Patterns 62

'Sublime Stitches' Aida Page 5 Patterns 62- 74 Full Design Area: 16.07 x 29.57 inches worked on 14 count AIDA 225 x 414 stitches Material: Minimum size - 26 x 40 inches to allow for embroidery frame and mounting Suggested fabric: Zweigart 14 count Aida, white, antique white or cream The sample was worked on Zweigart 14 count Aida, white Over dyed or space dyed fabrics may detract from the design - select carefully! There are 12 pages of patterns. One page will be placed in 'Freebies' in Blackwork Journey every month. Each pattern or group of patterns have their: Individual numbers, Technique, Threads and beads used, Chart, Picture and Method. Each month join a printout of the chart to the one before. The final chart will consist of 12 pages arranged in the order as shown above. Please follow the main chart carefully to place and work the different patterns. The embroidery may differ slightly. Where patterns overlap between the pages do not start the pattern. The part patterns are there to help in the placing of the design. As additional pages are added the part patterns will be complete. Do not add beads to the design until all 12 pages have been worked. The sample was worked in DMC and Anchor floss in four shades including DMC 310 as the base colour. Cross stitch is worked in TWO strands over two threads, back stitch is worked in ONE strand over two threads. Threads used: DMC 310 Black, three skeins Anchor 1206 variegated, or DMC 815 Garnet, three skeins DMC 415 Pearl grey, one skein DMC 414 Steel grey, one skein Metallic threads used: Rainbow Gallery Petite Treasure Braid PB01, one card or DMC Lights Effects E3852 Dark Gold, one skein DMC Lights Effects E317 DMC 996 electric blue is used on the chart to show ONE strand of 415 and ONE strand 414 together to make two strands for pulled thread work stitches. -

Basic Needlepoint

VISIT OUR OTHER NEEDLEARTS BASIC NEEDLEPOINT TUTORIALS AT www.beadseast.com WHAT YOU’LL NEED: Needlepoint canvas, 3” larger than your desired finished size; fiber appropriate to the gauge of the needlepoint canvas (in our tutorial we’ll assume you’re using 14-to-the-inch interlock canvas and a full strand of embroidery floss or tapestry wool); #10 embroidery needle or size 24 tapestry needle; masking tape; scissors 15 19 23 17 21 18 16 24 20 Before beginning, tape the edge of your canvas with masking tape and22 round the edges (photo, above) to minimize tangling or catching. Secure threads by holding one inch on the back of the canvas and catching the thread end in the first few stitches; end a thread by running it under stitches on the back of the canvas, one or more times until secure. When deciding where to start, allow a margin of about 1.5” all around, which will allow enough margin for blocking should it be necessary. There are three basic stitches used in traditional needlepoint: Continental stitch, half-cross stitch, and basketweave stitch. You’ll probably use all three within each project. 22 20 8 6 2 2 4 6 8 10 12 21 19 7 5 1 1 3 5 7 9 11 24 18 10 4 13 15 19 23 17 21 9 18 16 24 23 20 14 22 17 3 26 16 12 25 15 11 28 14 27 13 HALF-CROSS STITCH is also worked in 2 4 6 8 10 12 30 back and forth rows with a rotation of the1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 19 23 17 canvas at the end of the row. -

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry The Bayeux Tapestry A Critically Annotated Bibliography John F. Szabo Nicholas E. Kuefler ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by John F. Szabo and Nicholas E. Kuefler All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Szabo, John F., 1968– The Bayeux Tapestry : a critically annotated bibliography / John F. Szabo, Nicholas E. Kuefler. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-5155-7 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-5156-4 (ebook) 1. Bayeux tapestry–Bibliography. 2. Great Britain–History–William I, 1066–1087– Bibliography. 3. Hastings, Battle of, England, 1066, in art–Bibliography. I. Kuefler, Nicholas E. II. Title. Z7914.T3S93 2015 [NK3049.B3] 016.74644’204330942–dc23 2015005537 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed