Implementation of Maternal Health Financial Scheme in Rural Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2019-2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 ISO 9001: 2015 CERTIFIED ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 ISO 9001: 2015 CERTIFIED VISION Economic upliftment of the country by reaching electricity to all through reliable transmission. MISSION Efficient and effective management of national power grid for reliable and quality transmission as well as economic dispatch of electricity throughout the country. gywRee‡l© RvwZi wcZv e½eÜz †kL gywReyi ingvb I Zuvi cwiev‡ii knx` m`m¨‡`i cÖwZ web¤ª kÖ×v gywRee‡l© wcwRwmweÕi M„nxZ K‡g©v‡`¨vM RvwZi wcZv e½eÜz †kL gywReyi ingv‡bi Rb¥kZevwl©Kx myôyfv‡e D`hvc‡bi j‡¶¨ wcwRwmwe wb‡¤œv³ Kg©cwiKíbv MÖnY I ev¯Íevqb Ki‡Q Kg©cwiKíbv Ges miKvwi wb‡`©kbv ev¯Íevq‡bi j‡¶¨ wcwRwmwe GKwU g~j KwgwU Ges cvuPwU DcKwgwU MVb K‡i‡Q| kZfvM we`y¨Zvqb Kvh©µg ev¯Íevqb msµvšÍ K) 2020 mv‡ji g‡a¨ ‡`ke¨vcx kZfvM we`y¨Zvq‡bi j‡¶¨ wbf©i‡hvM¨ we`y¨r mÂvjb Kiv; L) ‰e`y¨wZK miÄvgvw`i Standard Specification ‰Zixi D‡`¨vM MÖnY; M) we`y¨r mÂvj‡bi ‡¶‡Î wm‡óg jm ‡iv‡a Kvh©Kix c`‡¶c MÖnY; N) we`y¨r wefv‡Mi mswkøó KwgwU KZ©…K M„nxZ Kvh©µ‡gi mv‡_ mgš^q K‡i cª‡qvRbxq Ab¨vb¨ Kvh©µg MÖnY; DrKl©Zv Ges D™¢vebx Kg©KvÛ msµvšÍ K) gywRe el©‡K we`y¨r wefvM KZ©…K Ô‡mev el©Õ wn‡m‡e ‡Nvlbvi ‡cÖw¶‡Z ‡m Abyhvqx Kvh©µg m¤úv`b Kiv; L) ‰e`y¨wZK Lv‡Z ‡`‡k I we‡`‡k `¶ Rbkw³i Pvwn`v c~iYK‡í ‰e`y¨wZK Kg©‡ckvq `¶ Rbkw³ M‡o ‡Zvjvi Rb¨ ÔgywRe e‡l©Õ cÖwk¶Y Kg©m~wPi gva¨‡g b~¨bZg 210 Rb †eKvi hyeK‡K gvbe m¤ú‡` iƒcvšÍi Kiv; M) e½eÜy ‡kL gywReyi ingv‡bi Rb¥kZevwl©Kx D`hvc‡bi j‡¶¨ ‰ZwiK…Z ‡K›`ªxq I‡qemvB‡Ui m‡½ wcwRwmweÕi wjsK ¯’vcb; N) we`y¨r wefv‡Mi mswkøó KwgwU KZ©…K M„nxZ Kvh©µ‡gi mv‡_ mgš^q K‡i cÖ‡qvRbxq -

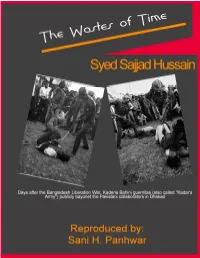

The Wastes of Time by Syed Sajjad Hussain

THE WASTES OF TIME REFLECTIONS ON THE DECLINE AND FALL OF EAST PAKISTAN Syed Sajjad Husain 1995 Reproduced By: Sani H. Panhwar 2013 Syed Sajjad Syed Sajjad Husain was born on 14th January 1920, and educated at Dhaka and Nottingham Universities. He began his teaching career in 1944 at the Islamia College, Calcutta and joined the University of Dhaka in 1948 rising to Professor in 1962. He was appointed Vice-Chancellor of Rajshahi University July in 1969 and moved to Dhaka University in July 1971 at the height of the political crisis. He spent two years in jail from 1971 to 1973 after the fall of East Pakistan. From 1975 to 1985 Dr Husain taught at Mecca Ummul-Qura University as a Professor of English, having spent three months in 1975 as a Fellow of Clare Hall, Cambridge University. Since his retirement in 1985, he had been living quietly at home and had in the course of the last ten years published five books including the present Memoirs. He breathed his last on 12th January, 1995. A more detailed account of the author’s life and career will be found inside the book. The publication of Dr Syed Sajjad Husain’s memoirs, entitled, THE WASTES OF TIME began in the first week of December 1994 under his guidance and supervision. As his life was cut short by Almighty Allah, he could read and correct the proof of only the first five Chapters with subheadings and the remaining fifteen Chapters without title together with the Appendices have been published exactly as he had sent them to the publisher. -

Zila Report : Habiganj

POPULATION & HOUSING CENSUS 2011 ZILA REPORT : HABIGANJ Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics Statistics and Informatics Division Ministry of Planning BANGLADESH POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS 2011 Zila Report: HABIGANJ October 2015 BANGLADESH BUREAU OF STATISTICS (BBS) STATISTICS AND INFORMATICS DIVISION (SID) MINISTRY OF PLANNING GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH ISBN-978-984-33-8637-3 COMPLIMENTARY Published by Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Statistics and Informatics Division (SID) Ministry of Planning Website: www.bbs.gov.bd This book or any portion thereof cannot be copied, microfilmed or reproduced for any commercial purpose. Data therein can, however, be used and published with acknowledgement of their sources. Contents Page Message of Honorable Minister, Ministry of Planning …………………………………………….. vii Message of Honorable State Minister, Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Planning …………. ix Foreword ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. xi Preface …………………………………………………………………………………………………. xiii Zila at a Glance ………………………………………………………………………………………... xv Physical Features ……………………………………………………………………………………... xix Zila Map ………………………………………………………………………………………………… xx Geo-code ………………………………………………………………………………………………. xxi Chapter-1: Introductory Notes on Census ………………………………………………………….. 1 1.1 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………… 1 1.2 Census and its periodicity ………………………………………………………………... 1 1.3 Objectives ………………………………………………………………………………….. 1 1.4 Census Phases …………………………………………………………………………… 2 1.5 Census Planning …………………………………………………………………………. -

Draft Report, Mamoni Survey, RDW-Sylhet

Final Report_MaMoni Evaluation_Habiganj_Maternal & Newborn health 2010 Final Report Study Title: Evaluation of the ACCESS/Bangladesh and MaMoni Programs: Population-Based Surveys in the Sylhet Division of Bangladesh Baseline Evaluation on Maternal & Newborn Health, 2010 Habiganj Report prepared by: Child Health Unit of Public Health Sciences Division ICDDR,B 1 | P a g e Final Report_MaMoni Evaluation_Habiganj_Maternal & Newborn health 2010 Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge the large number of people and organizations that provided support in the completion of baseline evaluation survey on the maternal and newborn health indicators of the ‘MaMoni’ project in Habiganj. To begin with, we express our profound appreciation to the women and household members who took time out of their busy daily routines to answer the survey questions. We thank them for their patience and willingness to respond to questions of a sensitive nature. We would also like to thank the many community leaders and health facility workers who provided information to the survey team. Save the Children, USA provided financial support and substantive technical advice concerning the design, field work and preparation of this report. We extend our appreciation and gratitude to the members of MaMoni team, Save the Children USA in Bangladesh. We would like to acknowledge the tremendous support provided by the district and upazila GoB officials like; Civil Surgeon, Deputy Director-Family Planning, Upazila Health and Family Planning Officers, Upazila Nirbahi Officers, Upazila Family Planning officers. We also express our deep gratitude to the members of the local NGOs (Shimantik and FIVDB). Associates for Community and Population Research (ACPR), was the data collection and research partner in this survey. -

Economic Evaluation of Demand-Side Financing (Dsf) Program for Maternal Health in Bangladesh

Prepared Under HNPSP of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare ECONOMIC EVALUATION OF DEMAND-SIDE FINANCING (DSF) PROGRAM FOR MATERNAL HEALTH IN BANGLADESH February 2010 Recommended Citation: Hatt, Laurel, Ha Nguyen, Nancy Sloan, Sara Miner, Obiko Magvanjav, Asha Sharma, Jamil Chowdhury, Rezwana Chowdhury, Dipika Paul, Mursaleena Islam, and Hong Wang. February 2010. Economic Evaluation of Demand-Side Financing (DSF) for Maternal Health in Bangladesh. Bethesda, MD: Review, Analysis and Assessment of Issues Related to Health Care Financing and Health Economics in Bangladesh, Abt Associates Inc. Contract/Project No.: 81107242 / 03-2255.2-001-00 Submitted to: Helga Piechulek and Atia Hossain GTZ-Bangladesh House 10/A, Road 90, Gulshan-2 Dhaka 1212, Bangladesh Abt Associates Inc. 4550 Montgomery Avenue, Suite 800 North Bethesda, Maryland 20814 Tel: 301.347.5000. Fax: 301.913.9061 www.abtassociates.com In collaboration with: RTM International 581, Shewrapara, Begum Rokeya Sharoni, Mirpur Dhaka 1216, Bangladesh 2 Economic Evaluation of DSF Voucher Program in Bangladesh ECONOMIC EVALUATION OF DEMAND- SIDE FINANCING (DSF) FOR MATERNAL HEALTH IN BANGLADESH DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH. CONTENTS Acronyms.................................................................................... xiii Acknowledgments....................................................................... xv Executive Summary................................................................. -

Mamoni Integrated Safe Motherhood, Newborn Care, Family Planning Project

MaMoni Integrated Safe Motherhood, Newborn Care, Family Planning Project Dilara Begum of Turong village, Companiganj, Sylhet, gave birth to a baby girl in 2010 who did not move or breathe. The village doctor declared her dead. Thanks to MaMoni’s health promotion activities through community health workers, the local traditional birth attendant was able to revive this beautiful girl, Takmina Begum, who will turn four early next year. Annual Report October 1, 2012‐September 30, 2013 Submitted November 8, 2013 MaMoni FY13 Annual Report Submitted November 8, 2013 Page 1 List of Abbreviations ACCESS Access to Clinical and Community Maternal, Neonatal and Women’s Health Services ANC Antenatal Care A&T Alive and Thrive CAG Community Action Group CC Community Clinic CG/CCMG Community Group/Community Clinic Management Group CHW Community Health Workers CM Community Mobilization/Community Mobilizer CPR Contraceptive Prevalence Rate CS Civil Surgeon CSBA Community Skilled Birth Attendant CV Community Volunteer DDFP Deputy Director, Family Planning DGFP Directorate General of Family Planning DGHS Directorate General of Health Services ELCO Eligible Couple (for FP) EmOC Emergency Obstetric Care ENA Essential Nutrition Action ENC Essential Newborn Care ETAT Emergency Triage, Assessment and Treatment of Sick Newborn FIVDB Friends in Village Development, Bangladesh FPI Family Planning Inspector FWA Family Welfare Assistant FWV Family Welfare Visitor GOB Government of Bangladesh HA Health Assistant ICDDR,B International Centre for Diarrhoeal Diseases -

Mamoni FY'12 Annual Report Oct 2011-Sep 2012

MaMoni Integrated Safe Motherhood, Newborn Care and Family Planning Project Sr. Secretary, MOH&FW, Md. Humayun Kabir, learning how expecting mothers are mapped and tracked in Shibpasha union of Ajmiriganj, Habiganj district. “…The contribution USAID supported MaMoni has made in providing service in this remote and hard-to-reach area is imitable. Particularly, the initiative to increase institutional delivery here is very encouraging…”, he wrote. Annual Report October 1, 2011 – September 30, 2012 Submitted October 31, 2012 MaMoni FY’12 Annual Report | October 31, 2012 0 List of Abbreviations ACCESS Access to Clinical and Community Maternal, Neonatal and Women’s Health Services ACPR Associates for Community Population Research AED Academy for Educational Development A&T Alive and Thrive CAG Community Action Group CC Community Clinic CCMG Community Clinic Management Group CHW Community Health Workers CM Community MobiliZation/Community MobiliZer CS Civil Surgeon CSM Community Supervisor/MobiliZer DDFP Deputy Director, Family Planning DGFP Directorate General of Family Planning DGHS Directorate General of Health Services EmOC Emergency Obstetric Care ENC Essential Newborn Care FIVDB Friends in Village Development, Bangladesh FPI Family Planning Inspectors FWA Family Welfare Assistant FWV Family Welfare Visitors GOB Government of Bangladesh ICDDR,B International Centre for Diarrhoeal Diseases Research, Bangladesh IYCF Infant and Young Child Feeding IMCI Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses MCH Maternal and child health MCHIP Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program MNH Maternal and newborn health MOH&FW Ministry of Health and Family Welfare MWRA Married Women of Reproductive Age PHC Primary Health Care PNC Postnatal Care SBA Skilled Birth Attendant SMC Social Marketing Company SSFP Smiling Sun Franchise Project TBA Traditional birth attendant UPHCP Urban Primary Health Care Project WRA White Ribbon Alliance MaMoni FY’12 Annual Report | October 31, 2012 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A. -

List of Upazilas of Bangladesh

List Of Upazilas of Bangladesh : Division District Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Akkelpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Joypurhat Sadar Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Kalai Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Khetlal Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Panchbibi Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Adamdighi Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Bogra Sadar Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Dhunat Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Dhupchanchia Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Gabtali Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Kahaloo Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Nandigram Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Sariakandi Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Shajahanpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Sherpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Shibganj Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Sonatola Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Atrai Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Badalgachhi Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Manda Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Dhamoirhat Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Mohadevpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Naogaon Sadar Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Niamatpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Patnitala Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Porsha Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Raninagar Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Sapahar Upazila Rajshahi Division Natore District Bagatipara -

Mamoni Semi-Annual Report

MaMoni Integrated Safe Motherhood, Newborn Care and Family Planning Project Semi‐Annual Report October 1, 2010 – March 31, 2011 Submitted April 30, 2011 MaMoni Semi‐Annual Report, October, 2010 – March, 2011 | April 30, 1 2011 List of Abbreviations ACCESS Access to Clinical and Community Maternal, Neonatal and Women’s Health Services AED Academy for Educational Development A&T Alive and Thrive CAG Community Action Group CC Community Clinic CCMG Community Clinic Management Group CHW Community Health Workers CM Community Mobilization/Community Mobilizer CS Civil Surgeon CSM Community Supervisor/Mobilizer DDFP Deputy Director, Family Planning DGFP Directorate General of Family Planning DGHS Directorate General of Health Services EmOC Emergency Obstetric Care ENC Essential Newborn Care FIVDB Friends in Village Development, Bangladesh FPI Family Planning Inspectors FWA Family Welfare Assistant FWV Family Welfare Visitors GOB Government of Bangladesh ICDDR,B International Centre for Diarrhoeal Diseases Research, Bangladesh IYCF Infant and Young Child Feeding IMCI Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses MCH Maternal and child health MCHIP Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program MNH Maternal and newborn health MOH&FW Ministry of Health and Family Welfare MWRA Married Women of Reproductive Age PHC Primary Health Care PNC Postnatal Care SBA Skilled Birth Attendant SMC Social Marketing Company SSFP Smiling Sun Franchise Project TBA Traditional birth attendant UPHCP Urban Primary Health Care Project WRA White Ribbon Alliance MaMoni Semi‐Annual -

Inventory of LGED Road Network, March 2005, Bangladesh

The Chief Engineer Local Government Engineering Department PREFACE It is a matter of satisfaction that LGED Road Database has been published through compilation of data that represent all relevant information of rural road network of the country in a structured manner. The Rural Infrastructure Maintenance Management Unit of LGED (former Rural Infrastructure Maintenance Cell) took up the initiative to create a road inventory database in mid nineties to register all of its road assets country-wide with the help of customized software called, Road and Structure Database Management System. The said database was designed to accommodate all relevant information on the road network sequentially and the system was upgraded from time to time to cater the growing needs. In general, the purpose of this database is to use it in planning and management of LGED's rural road network by providing detailed information on roads and structures. In particular, from maintenance point of view this helps to draw up comprehensive maintenance program including rational allocation of fund based on various parameters and physical condition of the road network. According to recent road re-classification, LGED is responsible for construction, development and maintenance of three classes of roads, which has been named as Upazila Road, Union Road and Village Road (category A & B) in association with Local Government Institution. The basic information about these roads like, road name, road type, length, surface type, condition, structure number with span, existing gaps with length, etc. has been made available in the road inventory. Side by side, corresponding spatial data are also provided in the road map comprising this document. -

Bibiyana II Gas Power Project

Draft Environment and Social Compliance Audit Project Number: 44951 July 2014 BAN: Bibiyana II Gas Power Project Prepared by Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies and ENVIRON UK Limited for Summit Bibiyana II Power Company Limited The environment and social compliance audit report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff. Your attention is directed to the “Terms of Use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Preliminary Environmental and Social Audit (Construction Phase) Summit Bibiyana II Power Company Limited Project Parkul, Nabigonj, Habigonj, Bangladesh Prepared for: Summit Bibiyana II Power Company Limited Date and Version: July 2014 nd 2 Draft, Version 1 Author: Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies (BCAS) House 10, Road 16A, Gulshan-1, Dhaka-1212, Bangladesh Tel: (880-2) 8818124-27, 8852904, 8851237, Fax: (880-2) 8851417 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.bcas.net Contributor: ENVIRON UK Limited 8 The Wharf, Bridge Street, Birmingham, UK Tel: +44 (0)121 616 2180 Version Control The Preliminary Environmental and Social Audit report has been subject to the following revisions: First Draft Title: Preliminary Environmental and Social Audit report Date: July 2014 Author: Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies (BCAS) Contributor: ENVIRON UK Ltd Second Draft Title: Preliminary Environmental and Social Audit report Date: July 2014 Author: Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies (BCAS) Contributor: ENVIRON UK Ltd Table of Contents 1. -

Religious Militancy in Bangladesh (2013-2016)

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS) |Volume IV, Issue VI, June 2020|ISSN 2454-6186 Religious Militancy in Bangladesh (2013-2016) Mohd Amdadul Haque, Sadia Afrin and Foisal Ahmed Lecturer, Political Science at Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Science & Technology University, Gopalganj-8100, Bangladesh Abstract: Religious militancy has come into focus all over the from an historic low of 4.1 in 2012 to 5.47 in 2013 to 5.92 in world after the attacks of the Al Qaeda in 2001 in New York. 2014. Bangladesh faced the largest bloody militant attack on Militancy denotes the activities of individuals, groups or parties first July 2016 at Holey Artisan Cafe in Dhaka at Gulshan to engage in violence with a particular ideological purpose. scored the death of 29 people (foreigners, police officers, Religiously inspired violent extremism and militancy emerged in gunmen, and bakery staff). Gulshan is the heart of the Bangladesh only in the mid-1990s. But during 2001 to 2006, militancy in Bangladesh got a profound root through links and diplomatic zone and this incident impacted Bangladesh‟s networks with global militant organizations. After a short break relations with countries and development partners. the issue of militancy again has come into forefront in 2013 with Bangladesh had to go through a tough examination after the old and new networks following the wave of transnational trend. dreadful attack. However, this increasing trend compels the Militant organizations attacked bloggers, foreigners, atheists, necessity to study the causes and factors responsible for the priests, non-Muslims and other targeted individuals.