Current Research in New York Archaeology: A.D. 700–1300

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greene County Open Space and Recreation Plan

GREENE COUNTY OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN PHASE I INVENTORY, DATA COLLECTION, SURVEY AND PUBLIC COMMENT DECEMBER 2002 A Publication of the Greene County Planning Department Funded in Part by a West of Hudson Master Planning and Zoning Incentive Award From the New York State Department of State Greene County Planning Department 909 Greene County Office Building, Cairo, New York 12413-9509 Phone: (518) 622-3251 Fax: (518) 622-9437 E-mail: [email protected] GREENE COUNTY OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN - PHASE I INVENTORY, DATA COLLECTION, SURVEY AND PUBLIC COMMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 II. Natural Resources ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 A. Bedrock Geology ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 1. Geological History ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 2. Overburden …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 3. Major Bedrock Groups …………………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 B. Soils ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 1. Soil Rating …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 7 2. Depth to Bedrock ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 7 3. Suitability for Septic Systems ……………………………………………………………………………………… 8 4. Limitations to Community Development ………………………………………………………………… 8 C. Topography …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 9 D. Slope …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 10 E. Erosion and Sedimentation ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 11 F. Aquifers ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

A Long-Term Prehistoric Occupation in the Hudson Valley

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 4-23-2018 The Roscoe Perry House Site: A Long-Term Prehistoric Occupation in the Hudson Valley Dylan C. Lewis CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/339 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Roscoe Perry House Site: A Long-Term Prehistoric Occupation in the Hudson Valley by Dylan C. F. Lewis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology, Hunter College The City University of New York 2018 Thesis Sponsor: April 23, 2018 Dr. William J Parry Date Signature April 23, 2018 Dr. Joseph Diamond Date Signature of Second Reader Acknowledgments: I would like to thank Dr. Joseph Diamond for providing me with a well excavated and informative archaeological collection from the SUNY New Paltz Collection. Without which I would have been unable to conduct research in the Hudson Valley. I would like to thank Dr. William Parry for so generously taking me on as a graduate student. His expertise in lithics has been invaluable. Thank you Glen Kolyer for centering me and helping me sort through the chaos of a large collection. Frank Spada generously gave his time to help sort through the debitage. Lastly, I would like to thank my wife to be for supporting me through the entire process. -

Plant Rarity Under Federal and State Laws and Regulations

Plant Rarity Under Federal and State Laws and Regulations Various government laws, regulations and policies protect rare plants. Probably the most surprising aspect of rare plant protection is that, unlike animals, plants are the property of the landowner whether that might be an individual, corporation, or government agency. This means that the protection of rare plants is under control of the landowner unless, in some cases, a government-regulated action is affecting them. Then the government entity regulating the action may require that protection efforts take place to preserve the rare plants and their habitat. Federal Law One of the results of the environmental movement of the 1960s and 70s was the enactment of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (https://www.fws.gov/endangered/laws-policies/index.html). The Act was designed to prevent the extinction of plants and animals, addressing problems of both exploitation and habitat destruction. The Act defines an endangered species as any species of animal or plant that is in danger of extinction over all or a significant portion of its range. A threatened species is defined as one that is likely to become endangered. The Act regulates the "taking" of endangered and threatened plants on federal land or when they are affected by federal actions or the use of federal funds. Specific protection is outlined in the Endangered Species Act of 1973 and states: It is unlawful for any person subject to the jurisdiction of the United States to: import any such species into, or export any such species -

Society for American Archaeology 16(1) January 1998

Society for American Archaeology 16(1) January 1998 "To present Seattle, my goal was to do a systematic survey. My pedestrian transects would be north and south along First, Second, etc., with perpendicular transects along cross streets. In addition to a typical restaurant list, I envisioned presenting the data as a chloropleth map showing the density of (1) coffee shops suitable for grabbing a continental-style breakfast, (2) establishments with large selections of microbrews on tap, and (3) restaurants that smelled really good at dinner time. " Click on the image to go to the article TABLE OF CONTENTS Editor's Corner Update on ROPA From the President Report--Board of Directors Meeting Archaeopolitics In Brief... Results of Recent SAA Balloting SAA Audited 1997 Financial Statement Working Together--White Mountain Apache Heritage Program Operations and Challenges Report from Seattle Student Affairs--Making the Most of Your SAA Meeting Experience The Native American Scholarships Committee Silent Auction in Seattle Archaeological Institute of America Offers Public Lectures The 63rd Annual Meeting is Just around the Corner From the Public Education Committee Electronic Quipus for 21st Century: Andean Archaeology Online Interface--Integration of Global Positioning Systems into Archaeological Field Research James Bennett Griffin, 1905-1997 Bente Bittmann Von Hollenfer, 1929-1997 Insights--Changing Career Paths and the Training of Professional Archaeologists SLAPP and the Historic Preservationist Books Received News and Notes Positions Open Calendar The SAA Bulletin (ISSN 0741-5672) is published five times a year (January, March, June, September, and November) and is edited by Mark Aldenderfer, with editorial assistance from Karen Doehner and Dirk Brandts. -

Glacial Lake Albany Butterfly Milkweed Plant Release Notice

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE BIG FLATS, NEW YORK AND ALBANY PINE BUSH PRESERVE COMMISSION ALBANY, NEW YORK AND THE NATURE CONSERVANCY EASTERN NEW YORK CHAPTER TROY, NEW YORK AND NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION ALBANY, NEW YORK NOTICE OF RELEASE OF GLACIAL LAKE ALBANY GERMPLASM BUTTERFLY MILKWEED The Albany Pine Bush Preserve Commission, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, The Nature Conservancy, and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, announce the release of a source-identified ecotype of Butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa L.). As a source identified release, this plant will be referred to as Glacial Lake Albany Germplasm butterfly milkweed, to document its original location. It has been assigned the NRCS accession number, 9051776. This alternative release procedure is justified because there is an immediate need for a source of local ecotype of butterfly milkweed. Plant material of this specific ecotype is needed for ecosystem and endangered species habitat restoration in the Pine Barrens of Glacial Lake Albany. The inland pitch pine - scrub oak barrens of Glacial Lake Albany are a globally rare ecosystem and provide habitat for 20 rare species, including the federally endangered Karner blue butterfly (Lycaeides melissa samuelis). The potential for immediate use is high and the commercial potential beyond Glacial Lake Albany is probably high. Collection Site Information: Stands are located within Glacial Lake Albany, from Albany, New York to Glens Falls, New York, and generally within the Albany Pine Bush Preserve, just west of Albany, New York. The elevation within the Pine Barrens is approximately 300 feet, containing a savanna-like ecosystem with sandy soils wind- swept into dunes, following the last glacial period. -

Midwest Choppers 2 Download Free

Midwest choppers 2 download free Artist: Tech N9ne, Song: Midwest Choppers 2 [extended](feat. K-Dean, Krayzie Bone, Twista), Duration: , Size: MB, Bitrate: kbit/sec, Type: mp3. Krayzie Bone & K-Dean) Tech N9ne - Midwest Chopper ツ Tech N9neツ - Midwest Choppers ft. D-Loc, Dalima & Big Kriz Tech N9ne - Midwest Choppers 2(feat. Midwest Choppers 2 by Tech N9ne feat. K-Dean and Krayzie We are considering introducing an ad-free version of WhoSampled. If you would be happy to pay. Stream Tech N9ne Midwest Choppers 2 Lyrics by yancydaveoo17 from desktop or your mobile device. Download. Tech N9ne - Midwest Choppers 2. Download. Tech N9ne - Midwest Choppers (feat. Big Krizz Kaliko, Dalima & D-Loc). Download. Tech N9ne "Midwest Choppers 2" ft. K-Dean & Krayzie Bone iTunes - Official Hip Hop. Midwest Choppers 2 Mp3. Free download Midwest Choppers 2 Mp3 mp3 for free. Tech N9ne - Midwest Choppers 2 (ft. K-Dean & Krayzie Bone). Source. View Lyrics for Midwest Choppers 2 by Tech N9ne at AZ Lyrics Sickology Midwest Choppers 2 AZ lyrics, find other albums and lyrics for Tech. Switch browsers or download Spotify for your desktop. Midwest Choppers 2. By Tech N9ne Collabos. • 1 song, Play on Spotify. 1. Midwest Choppers. Buy Midwest Choppers 2 [Clean]: Read 2 Digital Music Reviews - Buy Midwest Choppers 2 [Explicit]: Read 2 Digital Music Reviews - Start your day free trial of Unlimited to listen to this song plus tens of. Fast and free Tech N9ne Midwest Choppers Instrumental YouTube to MP3. Midwest Choppers 2 Remake On Fl Studio 9(instrumental)-unfinished (OLD) Tech N9ne - Worldwide Choppers FULL Instrumental Remake (with download link). -

Mohawk River Canoe Trip August 5, 2015

Mohawk River Canoe Trip August 5, 2015 A short field guide by Kurt Hollocher The trip This is a short, 2-hour trip on the Mohawk River near Rexford Bridge. We will leave from the boat docks, just upstream (west) of the south end of the bridge. We will probably travel in a clockwise path, first paddling west toward Scotia, then across to the mouth of the Alplaus Kill. Then we’ll head east to see an abandoned lock for a branch of the Erie Canal, go under the Rexford Bridge and by remnants of the Erie Canal viaduct, to the Rexford cliffs. Then we cross again to the south bank, and paddle west back to the docks. Except during the two river crossings it is important to stay out of the navigation channel, marked with red and green buoys, and to watch out for boats. Depending on the winds, we may do the trip backwards. The river The Mohawk River drains an extensive area in east and central New York. Throughout most of its reach, it flows in a single, well-defined channel between uplands on either side. Here in the Rexford area, the same is true now, but it was not always so. Toward the end of the last Ice Age, about 25,000 years ago, ice covered most of New York State. As the ice retreated, a large valley glacier remained in the Hudson River Valley, connected to the main ice sheet a bit farther to the north, when most of western and central New York was clear of ice. -

Greene County Grassland Habitat Management Plan

Greene County Grassland Habitat Management Plan Primary Authors: Karen Strong, Rene VanSchaack, and Ingrid Haeckel Contributing Authors: Abbe Martin (GCSWD) and Paul Novak Extra thanks for extensive comments and background material: Nancy Heaslip, Elizabeth LoGuidice, and Leslie Zucker. The Greene County Soil and Water Conservation District initiated the development of this management plan; however, a wide range of organizations and individuals played key roles in its development, and still more will have a role in implementation. Major project guidance was provided by the Greene County Habitat Advisory Committee, a unique partnership created to advise the Conservation District in habitat conservation. The following organizations and individuals are represented on the Greene County Habitat Advisory Committee and assisted in the development of this plan: The Greene County Habitat Advisory Committee Greene Land Trust: Bob Knighton Greene Industrial Development Agency: Rene VanSchaack Greene County Soil and Water Conservation District: Jeff Flack New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC): Paul Novak, Nancy Heaslip NYSDEC Hudson River Estuary Program: Karen Strong, Ingrid Haeckel Northern Catskills Audubon Society, Inc.: Larry Federman Scenic Hudson: Mark Wildonger, Chris Kenyon Hudsonia, Ltd.: Erik Kiviat, PhD. Cornell Cooperative Extension of Greene County’s Agroforestry Resource Center: Elizabeth LoGiudice Sierra Club, Hudson-Mohawk Group: Roger Downs Coxsackie Planning Board: Frank Gerrain Peter Feinberg, environmental consultant James Coe, artist, naturalist and field guide author Rich Guthrie, local bird expert New York State Department of Environmental Conservation provided funding for this project from the Environmental Protection Fund through the Hudson River Estuary Program. Suggested Citation: Strong, K., R. VanSchaack, and I. Haeckel. -

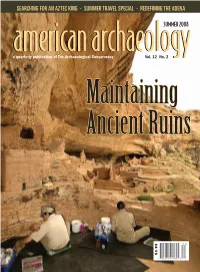

AA Sum08 Front End.Indd

SEARCHING FOR AN AZTEC KING • SUMMER TRAVEL SPECIAL • REDEFINING THE ADENA americanamerican archaeologyarchaeologySUMMER 2008 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 12 No. 2 Maintaining Ancient Ruins $3.95 AA Sum08 Front end.indd 1 5/13/08 9:04:25 PM AA Sum08 Front end.indd 2 5/13/08 9:04:43 PM american archaeologysummer 2008 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 12 No. 2 COVER FEATURE 27 SAVING RUINS FROM RUIN BY ANDREW LAWLER How do you keep ancient Southwest ruins intact? The National Park Service has been working to fi nd the answer. 12 IN SEARCH OF AN AZTEC KING BY JOHANNA TUCKMAN Archaeologists may be on the verge of uncovering a rare royal tomb in Mexico City. ROBERT JENSEN, MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK VERDE NATIONAL JENSEN, MESA ROBERT 20 REDEFINING THE ADENA BY PAULA NEELY Recent research is changing archaeologists’ defi nition of this remarkable prehistoric culture. 34 A DRIVING FORCE IN ARCHAEOLOGY BY BLAKE EDGAR The legendary Jimmy Griffi n made his many contributions outside of the trenches. 38 EXPLORING THE ANCIENT SOUTHWEST BY TIM VANDERPOOL JOHANNA TUCKMAN JOHANNA A tour of this region’s archaeological treasures makes for an unforgettable summer trip. 2 Lay of the Land 47 new acquisition 3 Letters PRESERVING A MAJOR COMMUNITY The Puzzle House Archaeological Community 5 Events could yield insights into prehistoric life in the 7 In the News Mesa Verde region. Oldest Biological Evidence of New World Humans? • Earliest Mesoamerican Cremations • Ancient Whaling COVER: Conservators Frank Matero (left) and 50 Field Notes Amila Ferron work in Kiva E at Long House in southwest Colorado’s Mesa Verde National Park. -

Route 14A Corridor Study Yates County, New York May 2006

Route 14A Corridor Study Yates County, New York Final Report May 2006 2230 Penfield Road Penfield, New York 14526 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Route 14A Advisory Committee Glenn Quackenbush, Benton Town Board Douglas Marchionda, Mayor, Village of Penn Yan & Yates County Legislator Steven Webster, Milo Town Board & Yates County Legislator Stewart Corse, Chairman, Town of Barrington Planning Board Judy Duquette, Trustee, Village of Dundee George Lawson, Supervisor, Town of Starkey David Hartman, Yates County Highway Superintendent Chris Wilson, Yates County Planning Jerry Stape, Yates County Planning Board Carroll Graves, Yates County Planning Board Steven Isaacs, Exec. Director, Yates County Industrial Development Agency Douglas Robb, Yates County Planning Board (former) Norman Snow, Supervisor, Town of Milo Yates County Legislators New York State Department of Transportation Robert Multer, Chairman William Piatt, NYSDOT Region 6 Patrick Flynn, Vice Chairman James Clements, NYSDOT Region 6 Donna Alexander Douglas Paddock Genesee Transportation Council Taylor Fitch Richard Perrin, Executive Director Michael Briggs Stephen Gleason, Executive Director (former) Donald House Deborah Flood Project Consultants Douglas Marchionda, Jr. Robert Elliott, P.E., Lu Engineers Robert Nielsen David Tuttle, P.E., Lu Engineers Nancy Taylor Frances Reese, Lu Engineers James Multer Elizabeth Cheteny, Allee, King, Rosen & Fleming Steven Webster Julie Salvo, Allee, King, Rosen & Fleming William Holgate Yates County Staff Special thanks to : Sarah Purdy, County Administrator -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-2-2017 On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy Evan Nave Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Nave, Evan, "On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 697. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/697 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON MY GRIND: FREESTYLE RAP PRACTICES IN EXPERIMENTAL CREATIVE WRITING AND COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY Evan Nave 312 Pages My work is always necessarily two-headed. Double-voiced. Call-and-response at once. Paranoid self-talk as dichotomous monologue to move the crowd. Part of this has to do with the deep cuts and scratches in my mind. Recorded and remixed across DNA double helixes. Structurally split. Generationally divided. A style and family history built on breaking down. Evidence of how ill I am. And then there’s the matter of skin. The material concerns of cultural cross-fertilization. Itching to plant seeds where the grass is always greener. Color collaborations and appropriations. Writing white/out with black art ink. Distinctions dangerously hidden behind backbeats or shamelessly displayed front and center for familiar-feeling consumption.