We Can Reduce Adverse Health Outcomes. It Is Our

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GREATER NEW HAVEN Community Index 2016

GREATER NEW HAVEN Community Index 2016 Understanding Well-Being, Economic Opportunity, and Change in Greater New Haven Neighborhoods A CORE PROGRAM OF In collaboration with The Community Foundation for Greater New Haven and other community partners and a Community Health Needs Assessment for the towns served by Yale-New Haven Hospital and Milford Hospital. Greater New Haven Community Index 2016 Understanding well-being, economic opportunity, and change in Greater New Haven neighborhoods MAJOR FUNDERS Other Funders The Greater New Haven Community Index makes extensive use of the 2015 DataHaven Community Wellbeing Survey, which completed in-depth interviews with 16,219 randomly-selected adults in Connecticut last year. In addition to the major funders listed above, supporters of the survey’s interviews with 1,810 adults in Greater New Haven as well as related data dissemination activities included the City of New Haven Health Department, United Way of Greater New Haven, Workforce Alliance, NewAlliance Foundation, Yale Medical Group, Connecticut Health Foundation, Connecticut Housing Finance Authority, and the Community Alliance for Research and Engagement at the Yale School of Public Health among others. Please see ctdatahaven.org for a complete list of statewide partners and funders. Lead Authors Mark Abraham, Executive Director, DataHaven Mary Buchanan, Project Manager, DataHaven Co-authors and contributors Ari Anisfeld, Aparna Nathan, Camille Seaberry, and Emma Zehner, DataHaven Amanda Durante and Fawatih Mohamed, University of Connecticut -

Report Appendices.Pdf

APPENDIX A Appendix A Sampling Methodology for DataHaven 2015 Survey Respondents are contacted via landline or cell phone. The design of the landline sample is conducted so as to ensure the selection of both listed and unlisted telephone numbers, using random digit dialing (RDD). The cell phone sample is drawn from a sample of dedicated wireless telephone exchanges from within Connecticut and the specified zip codes within New York State. Respondents are screened for residence in the state of Connecticut or one of the seven zip codes in New York. The primary supplier of the RDD landline and cell phone samples is Survey Sampling International (SSI) of Shelton, Connecticut, “the premier global provider of sampling solutions for survey research1”. From the SSI Fact Sheet on Radom Digit Samples (for landline telephone samples): Most SSI samples are generated using a database of “working blocks.” A block (also known as a 100-bank or a bank) is a set of 100 contiguous numbers identified by the first two digits of the last four digits of a telephone number. For example, in the telephone number 255-4200, “42” is the block. A block is termed to be working if one or more listed telephone numbers are found in that block. The sample composition is comprised of random numbers distributed across all eligible blocks in proportion to their density of listed telephone households. All blocks within a county are organized in ascending order by area code, exchange, and block number. Once the quota has been allocated to all counties in the frame, a sampling interval is calculated by summing the number of listed residential numbers in each eligible block within the county and dividing that sum by the number of sampling points assigned to the county. -

412!1202 1 2 J ?Hn De~Tefano

; (412!1202_1_2 J_?hn De~tefano , Jr. - RE: Cemetery tree planting 4/27-8 Page 1 1 From: "Richard Epstein" <[email protected]> To: "' John DeStefano, Jr."' <[email protected]> Date: 4/21/2011 11 :03 AM Subject: RE: Cemetery tree planting 4/27-8 Have not heard back from the RWA on the options available and the costs. told Andy to contact RWA and get the buckets. We are trying to implement the adopt the tree program at least for the short term. -----Original Message----- From: John DeStefano, Jr. [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Wednesday, April 20 , 2011 5:00 PM To: repstein@ lhbrennerins.com Subject: Fw: Cemetery tree planting 4/27-8 Water? No virus found in this outgoing message. Checked by AVG - www.avg .com Version : 9.0.894 I Virus Database: 271 .1.1/3587- Release Date: 04/21 /11 02 :34 :00 [_[~~?.~~-~~-~ -!2John DeStefano, Jr. - Re: Water Availability Page 1_] From: John DeStefano, Jr. To: [email protected] CC: [email protected] Date: 4/27/2011 10:39 AM Subject: Re : Water Availability Great. This is a terrific community project. Everyone appreciates RWA's time, effort and contribution to the project. And I thank you for your leadership. John -----Original Message----- From: "Larry Bingaman" <[email protected]> To: John DeStefano, Jr. <[email protected]> Sent: 4/27/2011 9:12:21 AM Subject: RE: Water Availability Dear Mayor DeStefano, This morning I received an update from our Manager of Contracts & New Services, David Johnson, on the status of providing irrigation water for the proposed street trees on Jewell St. -

GREATER NEW HAVEN Community Index 2016

GREATER NEW HAVEN Community Index 2016 Understanding Well-Being, Economic Opportunity, and Change in Greater New Haven Neighborhoods A CORE PROGRAM OF In collaboration with The Community Foundation for Greater New Haven and other community partners and a Community Health Needs Assessment for the towns served by Yale-New Haven Hospital and Milford Hospital. Greater New Haven Community Index 2016 Understanding well-being, economic opportunity, and change in Greater New Haven neighborhoods MAJOR FUNDERS Other Funders The Greater New Haven Community Index makes extensive use of the 2015 DataHaven Community Wellbeing Survey, which completed in-depth interviews with 16,219 randomly-selected adults in Connecticut last year. In addition to the major funders listed above, supporters of the survey’s interviews with 1,810 adults in Greater New Haven as well as related data dissemination activities included the City of New Haven Health Department, United Way of Greater New Haven, Workforce Alliance, NewAlliance Foundation, Yale Medical Group, Connecticut Health Foundation, Connecticut Housing Finance Authority, and the Community Alliance for Research and Engagement at the Yale School of Public Health among others. Please see ctdatahaven.org for a complete list of statewide partners and funders. Lead Authors Mark Abraham, Executive Director, DataHaven Mary Buchanan, Project Manager, DataHaven Co-authors and contributors Ari Anisfeld, Aparna Nathan, Camille Seaberry, and Emma Zehner, DataHaven Amanda Durante and Fawatih Mohamed, University of Connecticut -

Quinnipiac Meadows Railroad Name: Nhmaingis.DBO.Cityboundary Line Data Compiled from Various Sources

West Rock Amity Newhallville Prospect Beaver Hill Quinnipiac Hills East Rock Meadows Westville Dixwell NORTH Edgewood HAVEN Dwight Fair Haven West River Downtown Wooster Fair Sq/ Mill Haven River Heights Hill Long Wharf Annex Rd n Rd ernhard ave B H n le G d N d R East orwoo r r St e k D Shore ndo inste a a D Westm v e G r t O g e St A s id s d o c R b n t a a y l i e S t r p HAMDEN W i Po n n Pro i e vidence v St u A Q n r w se D to Melro e l Pa d wtucket Neighborhood Location id St M H a w t h o r n St e Cranston R r d D o Scarb d oro n a St G t Foxo S n Hill Rd t e s Ave s Smith o New b port St y E e AT C W IV ro PR ss S t F t io S re t S l t e v e s o e o v R A i r ie m 17 E l ll a is P S t C B l li u ff e T A e ss r um t pt S ion t S e t s s o b y e He F W S mi li un ng Roos nt s wa evelt S e y P St Ex t t R l t dg 103 e v St rt B A Albe a Quinnipiac c r A a n i v e p e s i n n i W Meadows u e Q l r t D o e na n n v Do S A t n S w aint o A t nth ony e l S d t East d d i r R M ny D p Ken t m an S u Lym Rock D Middletown ve F A o x B o lv n Rd d Emily F 5 ox 91 91 on Dani B el Dr lvd Qu inn ipia c C Barn t es Ave E a t s r S t D e l l e r t n e a S D t e v t S n A ow c et a dl i id p M i Rock n e St 80 n v i A u C Q l F i n a t o G w F r n o a n xo c A n e S B v l S t v e F d t ro nt St F Ol ox d on t Rd M e oxon St S a Av F on y D x n t o w o St to iley S F dle Ba w F id n e M i r n ry g S S t t t John r S on D r liams e il t l W a P Wilcox w t t S A x se r s EAST HAVEN P l Rio D E e V a D B i r e e St k r a Dove w P c L h l l n linton -

MOVE New Haven Study Overview

Transit Mobility Study 0 | Introduction Transit Mobility Study Chapter 1 Introduction ....................................................................................1 1.1 MOVE New Haven Study Overview ............................................................................. 1 1.2 Report Structure .................................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 2 Purpose and Need Statement ....................................................4 2.1 Purpose and Need of Study ........................................................................................... 4 2.2 Goals and Objectives ......................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 3 System Description .......................................................................7 3.1 System Overview ................................................................................................................. 7 3.2 CTtransit New Haven Routes .......................................................................................... 8 3.3 Route Profiles .................................................................................................................... 11 3.4 Ridership ............................................................................................................................. 16 3.5 Bus Stops............................................................................................................................. 25 3.6 -

Free COVID-19 Testing Sites Located Throughout Our City

Iline Tracey, Ed.D. P: (475) 220-1000 Superintendent F: (203) 946-7300 September 2020 Dear New Haven Learning Community, As we near the reopening of school, New Haven Public Schools is recommending COVID-19 testing for all staff and students. We encourage you to utilize the free COVID-19 Testing Sites that are located throughout our City: Established Testing Sites Pre-existing Testing Sites within the City: ADDRESS Day/Time Neighborhood New Haven Green 8 am-4 pm Wednesday Downtown 1319 Chapel Street 12 pm-5 pm Monday & Thursday Dwight 226 Dixwell Avenue 8:30 am-4:30 pm Monday-Friday Dixwell 428 Columbus Avenue 10 am-1 pm Monday-Friday Hill 185 Barnes Avenue 9 am-3:30 pm Various Days Quinnipiac Meadows 1471 Whalley Avenue 8 am-6 pm Various Days Amity 374 Grand Avenue 9 am-4:30 pm Fair Haven Schools with School-Based Health Clinic (SBHC) ADDRESS SBHC Neighborhood 35 Davis Street CSHHC AMITY 191 Fountain Street Yale AMITY 150 Fournier Street CSHHC BEAVER HILLS 480 Sherman Parkway Yale DIXWELL 259 Edgewood Avenue Yale DWIGHT 181 Mitchell Drive FHCHC EAST-ROCK 293 Clinton Avenue FHCHC FAIR-HAVEN 164 Grand Avenue FHCHC FAIR-HAVEN 100 James Street FHCHC FAIR-HAVEN 360 Columbus Avenue CSHHC HILL 140 Dewitt Street CSHHC HILL 140 Legion Avenue Yale HILL 560 Ella Grasso Blvd. BOE HILL 114 Truman Street CSHHC HILL 130 Bassett Street CSHHC NEWHALLVILLE 170 Derby Avenue Yale WESTRIVER 199-200 Wilmot Street NHHD West Rock Gateway Center | 54 Meadow Street, New Haven, CT 06519 Iline Tracey, Ed.D. -

GNHWPCA EJPPP Wet Weather Nitrogen Project Submission

Environmental Justice Public Participation Plan OP R ! "O! P"%%%& &' ' O P Part I: Proposed Applicant Information 1. APPLICANT INFORMATION Greater New Haven Water Pollution Control Authority 260 East Street New Haven CT 06511 203-466-5280 321 Tom Sgroi [email protected] R ✔ 2. WILL YOUR PERMIT APPLICATION INVOLVE: ✔ 3. FACILITY NAME AND LOCATION East Shore Water Pollution Abatement Facility & Pre-Treatment Sta. 345 East Shore Parkway (See Attached) New Haven CT 06512 052 950 400, 600, 800 Part II: Informal Public Meeting Requirements R A. Identify Time and Place of Informal Public Meeting date, time and placeR June 21, 2012 New Haven Sound School Regional Vocational Aquaculture Center, 60 South Water St., New Haven, CT 06519 6:30pm ! " # $ % & ' ( ) * ( ))) & B. Identify Communication Methods By Which to Publicize the Public Meeting New Haven Register and La Voz June 11, 2012 (NHR), June 8, 2012 (La Voz) +, - % ) . / & 0 ( 123+$!$+"3$$ # 3 "3 Part II: Informal Public Meeting Requirements (continued) ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ R Part III: Measures to Facilitate Meaningful Public Participation -

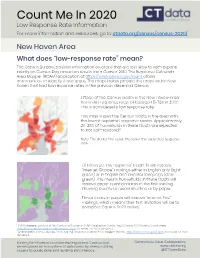

Count Me in 2020 Low Response Rate Information for More Information and Resources, Go to Ctdata.Org/Census/Census-2020

Count Me In 2020 Low Response Rate Information For more information and resources, go to ctdata.org/census/census-2020/ New Haven Area What does “low-response rate” mean? The Census Bureau provides information on areas that are less likely to self-respond initially on Census Day based on results from Census 2010. The Response Outreach Area Mapper (ROAM) application at https://www.census.gov/roam allows communities to identify these areas. The maps below provide the areas within New Haven that had low response rates in the previous decennial Census. Fifteen of the Census Tracts in the New Haven-area had initial response rates of between 5-73% in 2010.1 This is considered a low response rate. This map shows the Census Tracts in the area with 3508 the lowest expected response scores. Approximately 20-38% of households in these tracts are expected to not self—respond.2 Note: The darker the color, the lower the expected response rate. Of these 30 “low response” tracts, 10 will receive “Internet Choice” mailings either in English only (light green) or in English and another language (dark green). This means households in these tracts will receive paper questionnaires in the first mailing, allowing people to respond online or by paper. Those tracts in purple will receive “Internet First” mailings, which means their first invitation will be to complete Census 2020 online. 1 CUNY Mapping Services at the Center for Research, CUNY Graduation Center. (n.d.). Census 2020 Hard to Count map, https://www.censushardtocountmaps2020.us/. Accessed on 2020, January 6. 2 United States Census Bureau. -

Percentage of Owner Occupied Housing Units in New Haven for 2000 & 2010

PERCENTAGE OF OWNER OCCUPIED HOUSING UNITS IN NEW HAVEN FOR 2000 & 2010 2000 2010 West Rock West Rock 1413 1413 8.2% 12.2% Amity Amity 1412 1412 45.3% Newhallville Prospect Hill 43.8% Newhallville Prospect Hill Beaver Hills 1415 1418 1415 1418 1426.01 34.1% East Rock Quinnipiac Meadows Beaver Hills 1414 26.9% 29.7% 29.4% Quinnipiac Meadows 1426.01 1414 East Rock 43.6% 1419 1419 45.4% 23.8% Westville Dixwell 41.8% Dixwell 1416 22.5% 40.8% Westville 1411 1416 1410 Edgewood 20.2% 1411 50.1% Edgewood 1409 1410 22.2% 55.3% 1420 1409 1420 1425 3614.02 Fair Haven 1424 20.6% Dwight 1426.03 18.4% Dwight 3614.02 1426.03 1425 1407 Downtown 1421 1424 1407 1421 9.1% 8.3% Fair Haven 3614.01 6.5% Wooster Sq/ 25% Downtown 28.2% Fair Haven Wooster Sq/ 25% Mill River 3614.01 8.4% West River Heights West River Mill River Fair Haven 1401 1422 1408 1408 1422 1423 1423 Heights 20.9% 20.6% 1401 20.6% 1426.04 23.8% 1426.04 1406 1406 1403 26.2% 1403 Hill 24.6% 22.9% 1402 1405 Long Wharf Annex Annex Hill Long Wharf 1427 1402 1427 1405 0% 0% 38.3% 36.8% 1404 1404 Legend Legend 0.0 Percent (No Housing in Long Wharf) East Shore 0.0 (No Housing in Long Wharf) East Shore 1428 0.1 - 12.9 Percent 1428 77.5% 0.1 - 12.9 Percent 78.2% 13.0 - 25.8 Percent 13.0 - 25.8 Percent 25.9 - 38.8 Percent 25.9 - 38.8 Percent 38.9 - 51.7 Percent 38.9 - 51.7 Percent 51.8 - 77.5 Percent 51.8 - 78.2 Percent 1410 Census Tract Number 1410 Census Tract Number 77.5% Percentage of Owner Occupied Housing 78.2% Percentage of Owner Occupied Housing Note: City-Wide Owner Occupied Housing Percentage in 2000 : 29.5% Note: City-Wide Owner Occupied Housing Percentage in 2010 : 29.5% Source of Map Data: Partially based on 2010 Census neighborhood-level estimates created by DataHaven. -

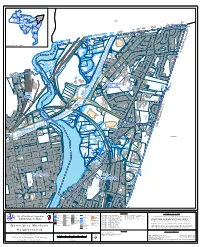

Fair Haven Greenway

Fair Haven Greenway Fair Haven Greenway Overview Vision The Fair Haven Greenway will loop around the bottom of the Fair Haven peninsula along the banks of the Mill and Quinnipiac River and then through the high peaks of East Rock Park. The Greenway will be an off-road paved path wherever space and existing conditions permit. In planning for the Fair Haven Greenway, every effort is made to align the trail as closely as possible to the shoreline of surrounding rivers. South of River Street and along the Mill River, the Greenway will introduce pedestrian/bicycle activities to areas that are predominantly industrial in character now. The Greenway will help create an awareness of and foster a relationship to the important natural resources of Fair Haven that are at certain points inaccessible to the residents of the surrounding neighborhoods. The greenway will also provide safer transportation routes to schools and job sites within Fair Haven. Key Points · Make rivers more accessible to pedestrian and bicycle activities. Create recreational opportunities, which are virtually non-existent at southern end of the Fair Haven peninsula. · Better define the geography of Fair Haven by allowing public access to its shoreline and the bodies of water that surround it and to the traprock ridges above it. Greenways and Cycling Systems, FH, Page 25 Fair Haven Greenway Existing Conditions FH – 1: Suzio Concrete – Criscuolo Park North of the existing Pearl Harbor Memorial “Q” Bridge is the Suzio Concrete facility. Along the shoreline of the facility, the City retains a public access easement (up to 130’ wide setback), which consists of a maintained lawn with wide vistas of the confluence of the Mill and Quinnipiac Rivers and Criscuolo Park. -

Substance Abuse & Mental Health

GREATER NEW HAVEN Community Index 2016 Understanding Well-Being, Economic Opportunity, and Change in Greater New Haven Neighborhoods A CORE PROGRAM OF In collaboration with The Community Foundation for Greater New Haven and other community partners and a Community Health Needs Assessment for the towns served by Yale-New Haven Hospital and Milford Hospital. Greater New Haven Community Index 2016 Understanding well-being, economic opportunity, and change in Greater New Haven neighborhoods MAJOR FUNDERS Other Funders The Greater New Haven Community Index makes extensive use of the 2015 DataHaven Community Wellbeing Survey, which completed in-depth interviews with 16,219 randomly-selected adults in Connecticut last year. In addition to the major funders listed above, supporters of the survey’s interviews with 1,810 adults in Greater New Haven as well as related data dissemination activities included the City of New Haven Health Department, United Way of Greater New Haven, Workforce Alliance, NewAlliance Foundation, Yale Medical Group, Connecticut Health Foundation, Connecticut Housing Finance Authority, and the Community Alliance for Research and Engagement at the Yale School of Public Health among others. Please see ctdatahaven.org for a complete list of statewide partners and funders. Lead Authors Mark Abraham, Executive Director, DataHaven Mary Buchanan, Project Manager, DataHaven Co-authors and contributors Ari Anisfeld, Aparna Nathan, Camille Seaberry, and Emma Zehner, DataHaven Amanda Durante and Fawatih Mohamed, University of Connecticut