State of Environment Report Himachal Pradesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Powered by Toursoft

Exotic Himachal-Do not change-Copy1 8 Days/7 Nights Powered by TourSoft Key Attractions Top 15 Places To Visit In Himachal Pradesh If you like anything and everything about snow, you may be inspired by the meaning of the word Himachal. ‘The land of snows’, the meaning, is adequate to give you an idea of what to expect here. Himachal Pradesh is located in the western Himalayas. Surrounded by majestic mountains, out of which some still challenge mankind to conquer them, the beauty of the land is beyond imagination. Simla, one of the most captivating hill stations, is the capital of the state. Given below are the top 15 places to visit in Himachal Pradesh. 1. Kullu Image credit – Balaji.B, CC BY 2.0 Kullu in Himachal Pradesh is one of the most frequented tourist destinations. Often heard along with the name Manali, yet another famous tourist spot, Kullu is situated on the banks of Beas River. It was earlier called as Kulanthpitha, meaning ‘The end of the habitable world’. Awe-inspiring, right? Kullu valley is also known as the ‘Valley of Gods’. Here are some leading destinations in the magical land. - Basheshwar Mahadev Temple - Sultanpur Palace - Parvati Valley - Raison - Raghunathji Temple - Bijli Mahadev Temple - Shoja - Karrain Bathad - Jagatsukh The attractions in Kullu are more. Trekking, mountaineering, angling, skiing, white water rafting and para gliding are some of the adventurous sports available here. 2. Manali Image credit – Balaji.B, CC BY 2.0 Located at an altitude of 6726 feet, Manali offers splendid views of the snow-capped mountains. -

Initial Environmental Examination IND:Himachal Pradesh Skills

Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 49108-002 June 2019 IND: Himachal Pradesh Skills Development Project Package : Rural Livelihood Center at Garola Panchayat, Bharmour, Chamba District (Himachal Pradesh) Submitted by: Government of Himachal Pradesh This initial environment examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 49108-002 April 2019 India: Himachal Pradesh Skill Development Project Name of the subproject: Rural Livelihood Center at Garola Panchayat, Bharmour, Chamba District (Himachal Pradesh) Prepared by the Government of Himachal Pradesh for the Asian Development Bank This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as -

History : Project Deepak

HISTORY : PROJECT DEEPAK 1. Raising & Early History. Project Deepak was raised in May 1961 with Col S N Punjh as Chief Engineer, primarily for the construction of Hindustan-Tibet (H-T) Road. The H-T Road is one of the most difficult roads ever to have been constructed in India. The 76 Km long Pooh-Kaurik sector of H-T Road passes through considerable lengths of sheer vertical hard rock stretches and huge bouldery strata embedded in sand and non-cohesive material, which is inherently unstable. The sector runs along the River Satluj crossing it at several locations. The road runs at altitudes between 1600 to 3600 meters. On the whole, the terrain and climatic conditions are very uncongenial. Many valuable lives were lost during the construction of this road. Thus, this work is a testimony to the sheer grit, determination and perseverance shown by PROJECT DEEPAK right from its early days. The subsequent major events in the history of Project Deepak include:- (a) In 1965, construction of the 122 Km long Road Dhami-Basantpur-Kiongal and 107 Km long stretch of Road Keylong-Sarchu (part of the Manali-Leh road) was entrusted to PROJECT DEEPAK. (b) In December 1966, following disbandment of Project Chetak, all roads of Uttaranchal were taken over by PROJECT DEEPAK. Thus, the 300 Km long Road Rishikesh –Joshimath-Mana, 63 Km long road Road Joshimath-Malari and 260 Km long Road Tanakpur-Askote-Tawaghat came under PROJECT DEEPAK. (c) The early seventies saw Project Deepak spreading its light (Deepak Jyoti) in the states of Rajasthan and even Punjab. -

General-STATIC-BOLT.Pdf

oliveboard Static General Static Facts CLICK HERE TO PREPARE FOR IBPS, SSC, SBI, RAILWAYS & RBI EXAMS IN ONE PLACE Bolt is a series of GK Summary ebooks by Oliveboard for quick revision oliveboard.in www.oliveboard.in Table of Contents International Organizations and their Headquarters ................................................................................................. 3 Organizations and Reports .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Heritage Sites in India .................................................................................................................................................. 7 Important Dams in India ............................................................................................................................................... 8 Rivers and Cities On their Banks In India .................................................................................................................. 10 Important Awards and their Fields ............................................................................................................................ 12 List of Important Ports in India .................................................................................................................................. 12 List of Important Airports in India ............................................................................................................................. 13 List of Important -

GAYATRI's I N S T I T U T E 1St Puliya C.H.B, Main Chopasni Road, Jodhpur. 9119119781 Page 1

Number Square Cube Square Root Cubic Root Number Square Cube Square Root Cubic Root x2 x3 x1/2 x1/3 x2 x3 x1/2 x1/3 1 1 1 1.000 1.000 61 3721 226981 7.810 3.936 2 4 8 1.414 1.260 62 3844 238328 7.874 3.958 3 9 27 1.732 1.442 63 3969 250047 7.937 3.979 4 16 64 2.000 1.587 64 4096 262144 8.000 4.000 5 25 125 2.236 1.710 65 4225 274625 8.062 4.021 6 36 216 2.449 1.817 66 4356 287496 8.124 4.041 7 49 343 2.646 1.913 67 4489 300763 8.185 4.062 8 64 512 2.828 2.000 68 4624 314432 8.246 4.082 9 81 729 3.000 2.080 69 4761 328509 8.307 4.102 10 100 1000 3.162 2.154 70 4900 343000 8.367 4.121 11 121 1331 3.317 2.224 71 5041 357911 8.426 4.141 12 144 1728 3.464 2.289 72 5184 373248 8.485 4.160 13 169 2197 3.606 2.351 73 5329 389017 8.544 4.179 14 196 2744 3.742 2.410 74 5476 405224 8.602 4.198 15 225 3375 3.873 2.466 75 5625 421875 8.660 4.217 16 256 4096 4.000 2.520 76 5776 438976 8.718 4.236 17 289 4913 4.123 2.571 77 5929 456533 8.775 4.254 18 324 5832 4.243 2.621 78 6084 474552 8.832 4.273 19 361 6859 4.359 2.668 79 6241 493039 8.888 4.291 20 400 8000 4.472 2.714 80 6400 512000 8.944 4.309 21 441 9261 4.583 2.759 81 6561 531441 9.000 4.327 22 484 10648 4.690 2.802 82 6724 551368 9.055 4.344 23 529 12167 4.796 2.844 83 6889 571787 9.110 4.362 24 576 13824 4.899 2.884 84 7056 592704 9.165 4.380 25 625 15625 5.000 2.924 85 7225 614125 9.220 4.397 26 676 17576 5.099 2.962 86 7396 636056 9.274 4.414 27 729 19683 5.196 3.000 87 7569 658503 9.327 4.431 28 784 21952 5.292 3.037 88 7744 681472 9.381 4.448 29 841 24389 5.385 3.072 89 7921 704969 9.434 -

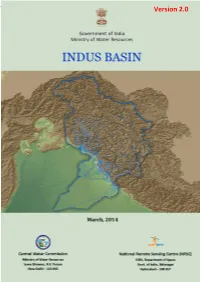

Purpose of Hydroelectric Generation.Only 13 Dams Are Used for Flood Control in the Basin and 19 Dams Are Used for Irrigation Along with Other Usage

Indus (Up to border) Basin Version 2.0 www.india-wris.nrsc.gov.in 1 Indus (Up to border) Basin Preface Optimal management of water resources is the necessity of time in the wake of development and growing need of population of India. The National Water Policy of India (2002) recognizes that development and management of water resources need to be governed by national perspectives in order to develop and conserve the scarce water resources in an integrated and environmentally sound basis. The policy emphasizes the need for effective management of water resources by intensifying research efforts in use of remote sensing technology and developing an information system. In this reference a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed on December 3, 2008 between the Central Water Commission (CWC) and National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) to execute the project “Generation of Database and Implementation of Web enabled Water resources Information System in the Country” short named as India-WRIS WebGIS. India-WRIS WebGIS has been developed and is in public domain since December 2010 (www.india- wris.nrsc.gov.in). It provides a ‘Single Window solution’ for all water resources data and information in a standardized national GIS framework and allow users to search, access, visualize, understand and analyze comprehensive and contextual water resources data and information for planning, development and Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM). Basin is recognized as the ideal and practical unit of water resources management because it allows the holistic understanding of upstream-downstream hydrological interactions and solutions for management for all competing sectors of water demand. -

E14650vol-02.Pdf

E1465 VOL. 2 WATER & ENVIRONMENT SATLUJ JAL VIDYUT NIGAM LIMITED Public Disclosure Authorized CUMMULATIVE AND INDUCED IMPACT ASSESSMENT RAMPUR HYDRO-ELECTRIC PROJECT (RHEP) Public Disclosure Authorized Di FINA REOR Public Disclosure Authorized *- -,.-,- , FINAL REPORT DHI (India) Water & Environment SEPTEMBER 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized I CUMMULATIVE AND INDUCED IMPACT K-71, First Floor ASSESSMENT Hauz Khas tnclave New Delhi 11 0016, India Tel: +91 11 2652 0425 FINAL REPORT Fax: +91 1126602276 September 2006 e-mail: [email protected] Web: www.dhi.dk Client Client's representative Satluj Jal Vidyut Nigam Ltd. Mr S. K. Sharma, SM (Quality Control/ER&R) Project Project No Cummulative and Induced Impact Assessment P3050220 (A) Authors Date Vimal Garg Sept 2006 Sonia Gujral Approved by Nidhi Sharma Poorva Gupta Ajay Pradhan SGU/NSA VGA AJP SEPT-06 Final Report Revi Description By Check Appro Date sion ed ved Key words Classification Hydroelectric Project F: Open Landuse River Profile F] Intemal Aquatic Ecology Socio-Economy Z Proprietary Cumulative impacts Distribution No of copies By: DHI, India I I TABLE OF CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................. 1-1 1.1 Power scenario and Need for the Study ......................................... 1-4 1.2 Objectives of the study ............................................. 1-5 1.3 Scope and Methodology adopted for the Study ........................... 1-6 1.3.1 Project Initiation .................................................. 1-7 1.3.2 Baseline Data Generation through Secondary Sources ...................... 1-8 1.3.3 Impact Analysis and Assessment ..................................... 1-8 1.3.4 Summary Recommendations ........................................ 1-9 1.4 Structure of the Report ............................................ 1-10 2 BASELINE SETUP OF THE AREA .................................... 2-1 2.1 River System of Himachal Pradesh ........................................ -

Model Career Center at Chamba Initial Environmental Examination

Initial Environmental Examination April 2021 India: Himachal Pradesh Skills Development Project Package : Model Career Center at Chamba Prepared by Government of Himachal Pradesh for the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Recd. on 19.4.21 SFG Log: 4604 Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 49108-002 April 2021 India: Himachal Pradesh Skill Development Project Sub-project– Model Career Center at Chamba Prepared by the Government of Himachal Pradesh for the Asian Development Bank This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other -

Dr. Abha Chauhan Khimta

TRIBAL DEVELOPMENT AND SOCIAL CHANGE: A STUDY OF DISTRICT KINNAUR OF HIMACHAL PRADESH Dr. Abha Chauhan Khimta TRIBAL DEVELOPMENT AND SOCIAL CHANGE: A STUDY OF DISTRICT KINNAUR OF HIMACHAL PRADESH Dr. Abha Chauhan Khimta Assistant Professor,Dept. of Political Science, Himachal Pradesh University, Summerhill, Shimla (HP) Email: [email protected] Abstract Himachal Pradesh is situated between 300-22’- 40’’ to 330-12’-20’’ north latitude and 750-45’-55’’ to 790- Reference to this paper 01’-22’’ east longitudes. The altitude in the Pradesh, a should be made as follows: wholly mountainous region in the lap of Himalayas ranges from 350 meters to 6975 meters above mean sea level. The Received: 15.04.2020 total area of Himachal Pradesh is 55673 square kilometer Approved: 30.06.2020 which is divided into twelve administrative districts. The Kinnaur and Lahaul Spiti districts and Pangi and Bharmpur Dr. Abha Chauhan Khimta (now tehsil Bharmour and sub tehsil Holi) Subdivision of TRIBAL DEVELOPMENT AND Chamba district constitute the schedule areas in the state. The tribal areas in the state have well defined SOCIAL CHANGE: administrative units. The (ITDP) Integrated Tribal A STUDY OF DISTRICT Development ProgrammeKinnaur comprises the whole KINNAUR OF HIMACHAL district. The present-day Kinnaur does not constitute a PRADESH homogeneous group and displays significant territorial and ethnic diversity. The Kinnaur district can be divided into RJPSSs 2020, Vol. XLVI, three territorial units to understand the territorial and ethnic No. 1, pp. 22-33 diversity of the district. The main focus of this research paper Article No.03 is to explore the development of this tribal area and how tribal development resulted in to the social change of the tribal people. -

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Approach and Studies Analyzing Resource Potential for Nature Based Tourism

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Approach and Studies ISSN NO:: 2348 – 537X Analyzing Resource Potential for Nature Based Tourism: A Case Study of the State of Himachal Pradesh (India) Punit Gautam Associate Professor, Department of Tourism and Hotel Management, North-Eastern Hill University, Shillong, Meghalaya (India) ―Potential‖ broadly insinuates something promising but not yet (fully) exploited; it symbolizes the sum total of qualitative and quantitative values of the given resources on which the degree and extent of its exploitability depends (Kandari, 1984). In the context of tourism, assessing the resource potential in quantitative terms is highly complex process, if not impossible, as it involves the physical, psychological and spiritual demands on the people belonging to diverse geographical, socio-cultural and economic backgrounds who travel under different motives, interests, preferences and immediate needs. To quote Kandari (1984), ―potential for tourism development in any area depends on the availability of recreational resources in addition to the factors like climate, seasons, accessibility, proximity to market, political stability, state of economy and general infrastructure, quality of natural environment, attitude of the local people, travel trade entrepreneurs and tourism planners, the existing tourist plant facilities and the degree to which they can be further developed within the prevailing limitations of natural, cultural and financial environments. Healthy combination of all those and many other factors -

Statewise Static GK Gr8ambitionz.Com National Parks

Statewise Static GK Gr8AmbitionZ.com National Parks State National Park Guru Ghasi Das Kalesar National Park (Sanjay) National Andhra Pradesh Kaziranga National Sultanpur National Park Park Park Papikonda National Goa Park Manas National Park Himachal Pradesh Bhagwan Mahavir Sri Venkateswara Nameri National Park Pin Valley National (Mollem) National National Park Park Rajiv Gandhi Orang Park Rajiv Gandhi National National Park Great Himalayan Gujarat Park National Park Bihar Blackbuck National Arunachal Pradesh Inderkilla National Valmiki National Park Park, Velavadar Park Namdapha National Chhattisgarh Gir Forest National Park Khirganga National Park Indravati National Park Mouling National Park Marine National Park, Park Simbalbara National Gulf of Kutch Kanger Valley Park Assam National Park Bansda National Park Jammu and Kashmir Dibru-Saikhowa Haryana Statewise Static GK Gr8AmbitionZ.com Dachigam National Anshi national park Madhav National Park Manipur Park Kerala Mandla Plant Fossils Keibul Lamjao NP Hemis National Park NP Eravikulam National Meghalaya Kishtwar National Park Panna National Park Balphakram National Park Mathikettan Shola Pench National Park Park Salim Ali NationaPark National Park Sanjay National Park Meghalaya Jharkhand Periyar National Park Satpura National Park Nokrek National Park Betla National Park Silent Valley National Van Vihar NP Mizoram Park Karnataka Maharashtra Murlen National Park Anamudi Shola Bandipur National National Park Chandoli NP Park Phawngpui Blue Pampadum Shola Gugamal NP Mountain NP Bannerghatta -

Format for Submision of Information on Proposed Action Plans for “Restoration of Polluted Water Bodies (Lakes and Ponds)”

FORMAT FOR SUBMISION OF INFORMATION ON PROPOSED ACTION PLANS FOR “RESTORATION OF POLLUTED WATER BODIES (LAKES AND PONDS)” IN COMPLIANCE TO HON’BLE NGT ORDERS DATED 10.5.2019 & 25.02.2020 IN O.A. NO. 325/2015 Submitted by: Himachal Pradesh State Wetlands Authority (HPSWA) H.P.Council for Science, Technology & Environment(HIMCOSTE) Vigyan Bhawan, Bemloe, Shimla 171001, H.P. 1 INDEX S.No Title Page number 1. Title page 1 2. Format of Submission of Information 3-5 3. Govind Sagar lake Information 6-8 4. Rewalsar lake Information 9-12 5. Pong Dam lake information 13-16 6. Dal Lake information 17-19 7. Khajjiar lake information 20-22 8. Renukaji information 23-25 9. Water Quality of Govind Sagar lake and 26 Rewalsar lake 10. Water Quality of Pong Dam lake 27-32 11. Water Quality of Khajjiar lake 33 12. Water Quality of Renukaji lake 34 2 FORMAT FOR SUBMISION OF INFORMATION ON PROPOSED ACTION PLANS FOR “RESTORATION OF POLLUTED WATER BODIES (LAKES AND PONDS)” IN COMPLIANCE TO HON’BLE NGT ORDERS DATED 10.5.2019 & 25.02.2020 IN O.A. NO. 325/2015 S. Content No 1 Name of the State/UT : Himachal Pradesh Contact Details : Name of the Name of the Contact Mobile E.mail (Department-wise) State/UT Nodal Officer Tel. No No. Department Himachal Mr. Nishant 0177- 7018323 Nishthak Pradesh State Thakur 265648 400 81@gmai Wetlands 9 l.com Joint Member Authority Secretary Department of Mr. Anil Thakur - 9418018 Dirindus- Industries 764 [email protected] Dy. Director, n Industries Department of Er.