Process Paper and Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3.2 Flood Level of Risk* to Flooding Is a Common Occurrence in Northwest Oregon

PUBLIC COMMENT DRAFT 11/07/2016 3.2 Flood Level of Risk* to Flooding is a common occurrence in Northwest Oregon. All Flood Hazards jurisdictions in the Planning Area have rivers with high flood risk called Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHA), except Wood High Village. Portions of the unincorporated area are particularly exposed to high flood risk from riverine flooding. •Unicorporated Multnomah County Developed areas in Gresham and Troutdale have moderate levels of risk to riverine flooding. Preliminary Flood Insurance Moderate Rate Maps (FIRMs) for the Sandy River developed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in 2016 •Gresham •Troutdale show significant additional risk to residents in Troutdale. Channel migration along the Sandy River poses risk to Low-Moderate hundreds of homes in Troutdale and unincorporated areas. •Fairview Some undeveloped areas of unincorporated Multnomah •Wood Village County are subject to urban flooding, but the impacts are low. Developed areas in the cities have a more moderate risk to Low urban flooding. •None Levee systems protect low-lying areas along the Columbia River, including thousands of residents and billions of dollars *Level of risk is based on the local OEM in assessed property. Though the probability of levee failure is Hazard Analysis scores determined by low, the impacts would be high for the Planning Area. each jurisdiction in the Planning Area. See Appendix C for more information Dam failure, though rare, can causing flooding in downstream on the methodology and scoring. communities in the Planning Area. Depending on the size of the dam, flooding can be localized or extreme and far-reaching. -

Shipping in Pacific Northwest Halted Due to Cracked Barge Lock at Bonneville Dam

Shipping in Pacific Northwest Halted Due to Cracked Barge Lock at Bonneville Dam Reports of a broken barge lock at the Bonneville Dam on the Columbia River surfaced on September 9th. The crack was discovered last week and crews began working Monday morning on repairs. The cause of the damage is unknown. To begin the repairs, the crews must first demolish the cracked concrete section. It remains unclear, however, when the repairs will be complete. Navigation locks allow barges to pass through the concrete dams that were built across the Columbia and Snake Rivers to generate hydroelectricity for the West. A boat will enter the lock which is then sealed. The water is then lowered or raised inside the lock to match the level of the river on the other side of the dam. When the levels match, the lock is then opened and the boat exits. The concrete that needs to be repaired acts as the seal for the lock. The damage to the concrete at the Bonneville Dam resulted in significant leaking—enough that water levels were falling when the lock was in operation. Thus, immediate repair was necessary. The Columbia River is a major shipping highway and the shutdown means barges cannot transport millions of tons of wheat, wood, and other goods from the inland Pacific Northwest to other markets. Eight million tons of cargo travel inland on the Columbia and Snake rivers each year. Kristin Meira, the executive director of the Pacific Northwest Waterways Association said that 53% of U.S. wheat exports were transported on the Columbia River in 2017. -

To Save the Salmon Here’S a Bit of History and Highlights of the Corps' Work to Assure Salmon Survival and Restoration

US Army Corps of Engineers R Portland District To Save North Pacific Region: Northwestern Division The Salmon Pacific Salmon Coordination Office P.O. Box 2870 Portland, OR 97208-2870 Phone: (503) 808-3721 http://www.nwd.usace.army.mil/ps/ Portland District: Public Information P.O. Box 2946 Portland, OR 97208-2946 Phone: (503)808-5150 http://www.nwp.usace.army.mil Walla Walla District: Public Affairs Office 201 N. 3rd Ave Walla Walla, WA 99362-1876 Phone: (509) 527-7020 http://www.nww.usace.army.mil 11/97 Corps Efforts to Save the Salmon Here’s a bit of history and highlights of the Corps' work to assure salmon survival and restoration. 1805-1900s: Lewis and Clark see “multitudes” 1951: The Corps embarks on a new research of migrating fish in the Columbia River. By program focusing on designs for more effective 1850, settlements bring agriculture, commercial adult fishways. fishing to the area. 1955: A fisheries field unit was established at 1888: A Corps report warns Congress of “an Bonneville Dam. There, biologists and enormous reduction in the numbers of spawning technicians work to better understand and fish...” in the Columbia River. improve fish passage conditions on the river 1900s-1930s: Overfishing, pollution, non- system. federal dams, unscreened irrigation ditches and 1960s: Experimental diversion screens at Ice ruined spawning grounds destroy fish runs. Harbor Dam guide some juveniles away from the Early hatchery operations impact habitat or turbine units, and lead to a major effort to develop close the Clackamas, Salmon and Grande Ronde juvenile bypass systems using screens for other rivers to salmon migration. -

Columbia River Treaty History and 2014/2024 Review

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers • Bonneville Power Administration Columbia River Treaty History and 2014/2024 Review 1 he Columbia River Treaty History of the Treaty T between the United States and The Columbia River, the fourth largest river on the continent as measured by average annual fl ow, Canada has served as a model of generates more power than any other river in North America. While its headwaters originate in British international cooperation since 1964, Columbia, only about 15 percent of the 259,500 square miles of the Columbia River Basin is actually bringing signifi cant fl ood control and located in Canada. Yet the Canadian waters account for about 38 percent of the average annual volume, power generation benefi ts to both and up to 50 percent of the peak fl ood waters, that fl ow by The Dalles Dam on the Columbia River countries. Either Canada or the United between Oregon and Washington. In the 1940s, offi cials from the United States and States can terminate most of the Canada began a long process to seek a joint solution to the fl ooding caused by the unregulated Columbia provisions of the Treaty any time on or River and to the postwar demand for greater energy resources. That effort culminated in the Columbia River after Sept.16, 2024, with a minimum Treaty, an international agreement between Canada and the United States for the cooperative development 10 years’ written advance notice. The of water resources regulation in the upper Columbia River U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Basin. -

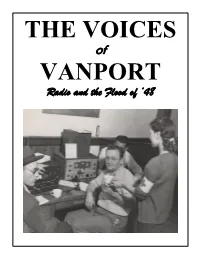

VANPORT Radio and the Flood of ‘48

51 THE VOICES of VANPORT Radio and the Flood of ‘48 Vanport Pg. 1 The Voices of Vanport Radio and the Flood of ‘48 By Dan Howard 2nd edition Copyright 2020 By Dan Howard, Portland Oregon Contact the author at [email protected] Cover: The title and cover layout were inspired by the short-lived The Voice of Vanport newspaper whose motto was “News of Vanport – By Vanporters – For Vanporters” Front Cover Caption: One of the several ham radio stations set up at the Red Cross Portland headquarters during the disaster. A WRL Globe Trotter transmitter is paired with a Hammarlund HQ-129-X receiver. The exhausted expressions tell the story of the long hours served by volunteers during the emergency. (Photo courtesy of Portland Red Cross Archives). The Voices of Vanport is an official publication of The Northwest Vintage Radio Society, organized in 1974 in Portland Oregon. Vanport Pg. 2 Voices of Vanport Table of Contents Page Dedication 5 Introduction 5 Part 1 - Flooding before The Flood 6 Origins of Vanport 10 KPQ 15 Three Cities & Three Rivers - Tri-Cities 18 Radio River Watch 19 W7JWJ – Harry Lewis 20 W7QGP – Mary Lewis 21 KVAN 23 KPDQ 28 KWJJ 31 Part 2 - Memorial Day 1948 35 The Vanport Hams 48 W7GXA – Joe Naemura 49 W7GBW & W7RVM - George & Helen Wise 50 KGW 51 W7HSZ – Rodgers Jenkins 59 KEX 63 Part 3 - The Response 65 KALE / KPOJ 78 Tom James 79 KOIN 82 KXL 85 The Truman Visit 87 Part 4 The Spread 91 Delta Park 92 W7AEF – Bill Lucas 98 W7ASF – Stan Rand 98 W7LBV – Chuck Austin 99 Vanport Pg. -

The Amazing Journey of Columbia River Salmon the Columbia River Basin

BONNEVILLE POWER ADMINISTRATION THE AMAZING JOURNEY OF Columbia River Salmon THE Columbia River Basin The Columbia River starts in Canada and flows through Washington. Then it flows along the Oregon and Washington border and into the Pacific Ocean. Other major rivers empty into the Columbia River. Smaller rivers and streams flow down from the mountains and into those rivers. This entire network of streams and rivers is called the Columbia River Basin. Salmon are born in many of these streams and rivers. They meet up with salmon from other places in the basin as they enter the Columbia River on their amazing journey to the ocean. This map shows the journey of the spring chinook that come from the Snake River in Idaho. Other spring chinook come from streams in Washington and Oregon. mbia lu o C MT N WA ake Sn Columb ia S n a k e OR ID Snak e CA NV LIFE CYCLE OF THE Columbia River Salmon RENEWING THE CYCLE 10 WAITING 1 TO HatCH RETURNING TO SPawNING 9 GROUNDS LEARNING 2 TO SURVIVE CLIMBING FISH 8 LADDERS LEAVING 3 HOME SWIMMING UPSTREAM 7 RIDING TO 4 THE SEA LIVING IN THE OCEAN 6 ENTERING 5 THE ESTUARY 1 ALEVIN REDD YOLK SAC FOUR MONTHS 1 Waiting to hatch Five thousand tiny red eggs lie hidden in a nest of stones Spring approaches, and the salmon slip out of their high in Northwest mountains. The cold, clear water of eggs. Barely an inch long, each of these just-born a shallow stream gently washes over the nest, called a fish, called ALEVIN, has large eyes and a bright orange REDD. -

Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History August 2009 6

HHHIIISSSTTTOOORRRIIICCC CCCOOOLLLUUUMMMBBBIIIAAA RRRIIIVVVEEERRR HHHIIIGGGHHHWWWAAAYYY OOORRRAAALLL HHHIIISSSTTTOOORRRYYY FFFiiinnnaaalll RRReeepppooorrrttt SSSRRR 555000000---222666111 HISTORIC COLUMBIA RIVER HIGHWAY ORAL HISTORY Final Report SR 500-261 by Robert W. Hadlow, Ph.D., ODOT Senior Historian Amanda Joy Pietz, ODOT Research and Hannah Kullberg and Sara Morrissey, ODOT Interns Kristen Stallman, ODOT Scenic Area Coordinator Myra Sperley, ODOT Research Linda Dodds, Historian for Oregon Department of Transportation Research Section 200 Hawthorne Ave. SE, Suite B-240 Salem OR 97301-5192 August 2009 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. OR-RD-10-03 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History August 2009 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Robert W. Hadlow, Ph.D., ODOT Senior Historian; Amanda Joy Pietz, ODOT Research; and Hannah Kullberg and Sara Morrissey, ODOT Interns ; Kristen Stallman, ODOT Scenic Area Coordinator; Myra Sperley, ODOT Research; and Linda Dodds, Historian 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Oregon Department of Transportation Research Section 11. Contract or Grant No. 200 Hawthorne Ave. SE, Suite B-240 Salem, OR 97301-5192 SR 500-261 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Oregon Department of Transportation Final Report Research Section 200 Hawthorne Ave. SE, Suite B-240 Salem, OR 97301-5192 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract The Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History Project compliments a larger effort in Oregon to reconnect abandoned sections of the Historic Columbia River Highway. -

CENTRAL OREGON N ABSTRACT* Byw.P.Kleweno,Jr., & R.M

Vol. 23, No.5 THE ORE.-BIN 43 May 1961 STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES Head Office: 1069 State Office Bldg., Portland 1, Oregon Telephone: CApitol 6-2161, Ext. 488 Field Offices 2033 First Street 239 S. E. "H" Street Baker Grants Pass * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * LEGISLATURE PASSES LAWS AFFECTING THE MINERAL INDUSTRY The fifty-first Legislative Assembly, which recessed May 10, considered and passed more legislation of importance to Oregon's mineral industry than any Legislature for a great many years. In general, three broad areas were covered --sand and gravel operations, the leasing of state lands for oil and gas investigations and operations, and placer mining. Two House Joint Memorials were acted on: HJM 11, urging the Federal Government to en courage the development of the mining industry, passed, while HJM 12, memorializing Congress to decl ine passage of legislotion to extend Wi Iderness areas, passed in the House but was tabled in the Natural Resources Committee of the Senate. As these laws will be of considerable importance to those interested in developing Oregon's mineral resources, brief explanations or section-by-section descriptions are given below. All of these bills have been signed by the Governor but only a few bore an emergency provision. There fore it will be some time in August before most take effect. Persons wishing to obtain copies of the acts should write to the Legislative Fiscal Committee, 313 State Capitol, Salem, Oregon. Legislation in regard to leasing of Oregon's offshore lands, leasing for hard rock minerals in the Lower Columbia River, and for pipelines across the ocean beach came about as the result of Opinion Nos. -

Water Temperatures in the Lower Columbia River

WATER TEMPERATURES IN THE LOWER COLUMBIA RIVER Water Temperatures in the Lower Columbia River ----------------------------~ GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 551 Washington 196 United States Department of the Interior STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary Geological Survey William T. Pecora, Director Free on application to the U.S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C. 20242 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract 1 Monthly profiles of water temperature Introduction __________________________________ _ 1 for August 1941 to July 1942 ------------------ 2 General background _______________________ _ 1 Explanation of profiles --------------------- 2 Purpose and scope ------------------------ 1 Interpretation of profiles ___________________ 10 Acknowledgments -------------------------- 1 Comparison with average conditions ----- 10 Daily water temperatures for 20 sites ____________ _ 2 Comparison with present conditions ----- 10 Conclusions ----------------------------------- 15 References ------------------------------------ 16 ILLUSTRATIONS Page Figure 1. Map showing study area and sites for which water temperatures are reported ________________ 2 2-7. Graphs of water-temperature profiles for lower Columbia River for- 2. August and September 1941 ------------------------------------------------------ 4 3. October and November 1941 ------------------------------------------------------- 5 4. December 1941 and January 1942 ------------------------------------------------- 6 5. February and March 1942 --------------------------------------------------------- 7 6. April and -

Second Powerhouse, Bonneville Lock and Dam, Columbia River, Oregon and Washington

FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT 15 NOVEMBER 1971 s* »21 SECONDi t r 4 mA EM, ISa E * BONNEVILLE LOCK ANB DALI COLUnOlVEB, O ’ OREGON AND D fiS K T ON 11 f n U ;S ARMY; ENGINEER DISTRICT * ' > r* 4 S J- . * ' ' 'PORTLAND/OREGON k - ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT SECOND POWERHOUSE, BONNEVILLE LOCK AND DAM, COLUMBIA RIVER, OREGON AND WASHINGTON Prepared by U.S. ARMY ENGINEER DISTRICT, PORTLAND, OREGON 15 November 1971 Second Powerhouse, Bonneville Lock and Dam, Columbia River, Oregon and Washington ( ) Draft ( X ) Final Environmental Statement Responsible Office; U. S. Army Engineer District, Portland, Oregon. 1. Name of Action: ( X ) Administrative ( ) Legislative 2. tenance of an eig existing Bonnevil County, Washingto 3a. Environmental Impacts Highway and railroad relocations, removal of existing town of North Bonneville, excavation and disposal of about 18 million cubic yards of material, loss of about 25 acres of wetlands, increased mortality of downstream migrant fish, elimination of a popular sport fishing site, reduction of nitrogen supersaturation downstream from Bonneville, increased dependable capacity and electrical energy production for the Pacific Northwest power system. b. Adverse Environmental Effects: Relocation of the citizens of North Bonneville, filling of 400 to 600 acres of low elevation area downstream of the project with 18 million cubic yards of rock and soil, temporary turbidity during construction, noise and air pollution associated with construction activities. 4. Alternatives: No action, different powerhouse size, different power house location, addition of new navigation lock. 5. Comments Received: Federal Environmental Protection Agency Bureau of Reclamation Forest Service Bureau of Sport Fisheries & Wildlife Nat'l Oceanic & Atmospheric Admin. Geological Survey National Marine Fisheries Service National Park Service Bonneville Power Administration U.S. -

Assessment of Coastal Water Resources and Watershed Conditions at Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, Oregon and Washington

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resources Program Center Assessment of Coastal Water Resources and Watershed Conditions at Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, Oregon and Washington Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRTR—2007/055 ON THE COVER Upper left, Fort Clatsop, NPS Photograph Upper right, Cape Disappointment, Photograph by Kristen Keteles Center left, Ecola, NPS Photograph Lower left, Corps at Ecola, NPS Photograph Lower right, Young’s Bay, Photograph by Kristen Keteles Assessment of Coastal Water Resources and Watershed Conditions at Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, Oregon and Washington Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRTR—2007/055 Dr. Terrie Klinger School of Marine Affairs University of Washington Seattle, WA 98105-6715 Rachel M. Gregg School of Marine Affairs University of Washington Seattle, WA 98105-6715 Jessi Kershner School of Marine Affairs University of Washington Seattle, WA 98105-6715 Jill Coyle School of Marine Affairs University of Washington Seattle, WA 98105-6715 Dr. David Fluharty School of Marine Affairs University of Washington Seattle, WA 98105-6715 This report was prepared under Task Order J9W88040014 of the Pacific Northwest Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Unit (agreement CA9088A0008) September 2007 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resources Program Center Fort Collins, CO i The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. -

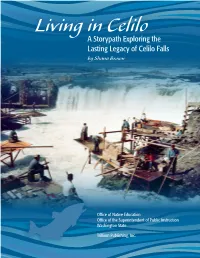

A Storypath Exploring the Lasting Legacy of Celilo Falls by Shana Brown

Living in Celilo A Storypath Exploring the Lasting Legacy of Celilo Falls by Shana Brown Office of Native Education Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction Washington State Trillium Publishing, Inc. Acknowledgements Contents Shana Brown would like to thank: Carol Craig, Yakama Elder, writer, and historian, for her photos of Celilo as well as her Introduction to Storypath ..................... 2 expertise and her children’s story “I Wish I Had Seen the Falls.” Chucky is really her first grandson (and my cousin!). Episode 1: Creating the Setting ...............22 The Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission for providing information about their organization and granting permission to use articles, including a piece from their Episode 2: Creating the Characters............42 magazine Wana Chinook Tymoo. Episode 3: Building Context ..................54 HistoryLink.org for granting permission to use the article “Dorothea Nordstrand Recalls Old Celilo Falls.” Episode 4: Authorizing the Dam ..............68 The Northwest Power and Conservation Council for granting permission to use an excerpt from the article “Celilo Falls.” Episode 5: Negotiations .....................86 Ritchie Graves, Chief of the NW Region Hydropower Division’s FCRPS Branch, NOAA Fisheries, for providing information on survival rates of salmon through the Episode 6: Broken Promises ................118 dams on the Columbia River system. Episode 7: Inundation .....................142 Sally Thompson, PhD., for granting permission to use her articles. Se-Ah-Dom Edmo, Shoshone-Bannock/Nez Perce/ Yakama, Coordinator of the Classroom-Based Assessment ...............154 Indigenous Ways of Knowing Program at Lewis & Clark College, Columbia River Board Member, and Vice President of the Oregon Indian Education Association, for providing invaluable feedback and guidance as well as copies of the actual notes and letters from the Celilo Falls Community Club.