Judeo-Christian Representations of Life, Death, and the Afterlife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wind Chasers Beware- Ecclesiastes 1

Wind Chasers Beware Eccleiase 1 Wisdom Literature While other civilizations shared in wisdom literature, the major difference is the Hebrew wisdom writings acknowledged one God, denying materialism and [the worship of many gods.] 2 Types of Wisdom Literature: Didactic (Practical/ Teaching) and Philosophical/Pessimistic (Critical/ Reflective/Questioning). The goal of wisdom is a proper relationship with YAHWEH. Wisdom Focus Didactic wisdom literature advocates the development of prudential habits, skills, and virtues. The aim is to develop moral character, personal success and happiness, safety, and well-being. Proverbs is an example of this type. Philosophical/Pessimistic wisdom literature delves deeper into issues facing mankind. It portrays the emptiness and folly of the search for insight and understanding apart from God. Job and Ecclesiastes are examples of this type. The words of the Preacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem. Ecclesiastes 1:1 Consider the Source Advice is only as good as the one giving it. Only 2 ways of learning something: Personal experience or 2nd hand. Solomon was the wisest man that ever lived. (See 1 Kings 3:11-14) Solomon saw one of Israel's wealthier periods. Ecclesiastes 1:2-6 “ Vanity of vanities,” says the Preacher, “Vanity of vanities! All is vanity.” What advantage does man have in all his work which he does under the sun? A generation goes and a generation comes, but the earth remains forever. Also, the sun rises and the sun sets; and hastening to its place it rises there again. Blowing toward the south, then turning toward the north, the wind continues swirling along; and on its circular courses the wind returns. -

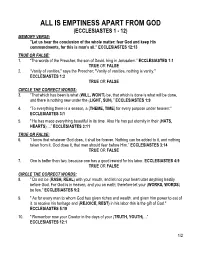

Is Emptiness Apart From

ALL IS EMPTINESS APART FROM GOD (ECCLESIASTES 1 - 12) MEMORY VERSE: "Let us hear the conclusion of the whole matter: fear God and keep His commandments, for this is man's all.” ECCLESIASTES 12:13 TRUE OR FALSE: 1. “The words of the Preacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem.” ECCLESIASTES 1:1 TRUE OR FALSE 2. “Vanity of vanities," says the Preacher; "Vanity of vanities, nothing is vanity." ECCLESIASTES 1:2 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORDS: 3. “That which has been is what (WILL, WON’T) be, that which is done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the (LIGHT, SUN)." ECCLESIASTES 1:9 4. "To everything there is a season, a (THEME, TIME) for every purpose under heaven:" ECCLESIASTES 3:1 5. " He has made everything beautiful in its time. Also He has put eternity in their (HATS, HEARTS) ...” ECCLESIASTES 3:11 TRUE OR FALSE: 6. “I know that whatever God does, it shall be forever. Nothing can be added to it, and nothing taken from it. God does it, that men should fear before Him.” ECCLESIASTES 3:14 TRUE OR FALSE 7. One is better than two, because one has a good reward for his labor. ECCLESIASTES 4:9 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORDS: 8. " Do not be (RASH, REAL) with your mouth, and let not your heart utter anything hastily before God. For God is in heaven, and you on earth; therefore let your (WORKS, WORDS) be few." ECCLESIASTES 5:2 9. " As for every man to whom God has given riches and wealth, and given him power to eat of it, to receive his heritage and (REJOICE, REST) in his labor-this is the gift of God." ECCLESIASTES 5:19 10. -

Freeing the Dead Sea Scrolls: a Question of Access

690 American Archivist / Vol. 56 / Fall 1993 Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/56/4/690/2748590/aarc_56_4_w213201818211541.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 Freeing the Dead Sea Scrolls: A Question of Access SARA S. HODSON Abstract: The announcement by the Huntington Library in September 1991 of its decision to open for unrestricted research its photographs of the Dead Sea Scrolls touched off a battle of wills between the library and the official team of scrolls editors, as well as a blitz of media publicity. The action was based on a commitment to the principle of intellectual freedom, but it must also be considered in light of the ethics of donor agreements and of access restrictions. The author relates the story of the events leading to the Huntington's move and its aftermath, and she analyzes the issues involved. About the author: Sara S. Hodson is curator of literary manuscripts at the Huntington Library. Her articles have appeared in Rare Books & Manuscripts Librarianship, Dictionary of Literary Biography Yearbook, and the Huntington Library Quarterly. This article is revised from a paper delivered before the Manuscripts Repositories Section meeting of the 1992 Society of American Archivists conference in Montreal. The author wishes to thank William A. Moffett for his encour- agement and his thoughtful and invaluable review of this article in its several revisions. Freeing the Dead Sea Scrolls 691 ON 22 SEPTEMBER 1991, THE HUNTINGTON scrolls for historical scholarship lies in their LIBRARY set off a media bomb of cata- status as sources contemporary with the time clysmic proportions when it announced that they illuminate. -

Ecclesiastes Song of Solomon

Notes & Outlines ECCLESIASTES SONG OF SOLOMON Dr. J. Vernon McGee ECCLESIASTES WRITER: Solomon. The book is the “dramatic autobiography of his life when he got away from God.” TITLE: Ecclesiastes means “preacher” or “philosopher.” PURPOSE: The purpose of any book of the Bible is important to the correct understanding of it; this is no more evident than here. Human philosophy, apart from God, must inevitably reach the conclusions in this book; therefore, there are many statements which seem to contra- dict the remainder of Scripture. It almost frightens us to know that this book has been the favorite of atheists, and they (e.g., Volney and Voltaire) have quoted from it profusely. Man has tried to be happy without God, and this book shows the absurdity of the attempt. Solomon, the wisest of men, tried every field of endeavor and pleasure known to man; his conclusion was, “All is vanity.” God showed Job, a righteous man, that he was a sinner in God’s sight. In Ecclesiastes God showed Solomon, the wisest man, that he was a fool in God’s sight. ESTIMATIONS: In Ecclesiastes, we learn that without Christ we can- not be satisfied, even if we possess the whole world — the heart is too large for the object. In the Song of Solomon, we learn that if we turn from the world and set our affections on Christ, we cannot fathom the infinite preciousness of His love — the Object is too large for the heart. Dr. A. T. Pierson said, “There is a danger in pressing the words in the Bible into a positive announcement of scientific fact, so marvelous are some of these correspondencies. -

Why Sacrifices in the Millennium

Scholars Crossing Article Archives Pre-Trib Research Center May 2009 Why Sacrifices in The Millennium Thomas D. Ice Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/pretrib_arch Recommended Citation Ice, Thomas D., "Why Sacrifices in The Millennium" (2009). Article Archives. 60. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/pretrib_arch/60 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Pre-Trib Research Center at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Article Archives by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHY LITERAL SACRIFICES IN THE MILLENNIUM Tom's Perspectives by Thomas Ice A common objection to the consistent literal interpretation of Bible prophecy is found in Ezekiel’s Temple vision (Ezek. 40—48). Opponents argue that if this is a literal, future Temple, then it will require a return to the sacrificial system that Christ made obsolete since the prophet speaks of “atonement” (kiper) in Ezekiel 43:13, 27; 45:15, 17, 20. This is true! Critics believe this to be a blasphemous contradiction to the finished work of Christ as presented in Hebrews 10. Hank Hanegraaff says that I have “exacerbated the problem by stating that without animal sacrifices in the Millennium, Yahweh’s holiness would be defiled. That, for obvious reasons, is blasphemous.” He further says that such a view constitutes a return “to Old Covenant sacrifices.”1 “Is it heretical to believe that a Temple and sacrifices will once again exist,” ask John Schmitt and Carl Laney? “Ezekiel himself believed it was a reality and the future home of Messiah. -

E Z E K I E L

E Z E K I E L —prophet to the exiles in Babylon, early sixth century. Name means “God will strengthen” 1. Date Ezekiel dates his prophecies very frequently, as much or more than any other OT book. There are 14 time-posts in Ezekiel, all in chronological order except 29:17 that has a logical connection to its context of Oracles against the Nations: 1:1 30th year (of what?) 1:2 5th year of Jehoiachin’s captivity 8:1 6th “ 20:1 7th 24:1 9th 26:1 11th 29:1 10th 29:17 27th 30:20 11th 31:1 11th 32:1 12th 32:17 12th 33:21 12th year of our captivity 40:1 25th “ Jehoiachin’s captivity started in 597 BC, the apparent terminus a quo: 5th year = 593 BC 27th year = 571 BC Note that many of these prophecies were given during his 11th and 12th years of captivity. That would be 587-586 BC, just during and after the fall and destruction of Jerusalem (cf. 33:21). Ezekiel 1:1 poses a question: the “30th year” of what? It could be the 30th year of the Neo-Babylonian empire (about 596 BC, assuming its beginnings under Nabopolassar in 626 BC), the year after Jehoiachin was taken captive, two years before Ezekiel’s call related in chapter 1. Another possibility is that it is Ezekiel’s age at the time of his call (cf. Num. 4:3, and the lives of John the Baptist and of Jesus, Lk. 3:23). The old critical view of C. -

From the Garden of Eden to the New Creation in Christ : a Theological Investigation Into the Significance and Function of the Ol

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2017 From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old estamentT imagery of Eden within the New Testament James Cregan The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Cregan, J. (2017). From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old Testament imagery of Eden within the New Testament (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/181 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM THE GARDEN OF EDEN TO THE NEW CREATION IN CHRIST: A THEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION INTO THE SIGNIFICANCE AND FUNCTION OF OLD TESTAMENT IMAGERY OF EDEN WITHIN THE NEW TESTAMENT. James M. Cregan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame, Australia. School of Philosophy and Theology, Fremantle. November 2017 “It is thus that the bridge of eternity does its spanning for us: from the starry heaven of the promise which arches over that moment of revelation whence sprang the river of our eternal life, into the limitless sands of the promise washed by the sea into which that river empties, the sea out of which will rise the Star of Redemption when once the earth froths over, like its flood tides, with the knowledge of the Lord. -

Ecclesiastes “Life Under the Sun”

Ecclesiastes “Life Under the Sun” I. Introduction to Ecclesiastes A. Ecclesiastes is the 21st book of the Old Testament. It contains 12 chapters, 222 verses, and 5,584 words. B. Ecclesiastes gets its title from the opening verse where the author calls himself ‘the Preacher”. 1. The Septuagint (the translation of the Hebrew into the common language of the day, Greek) translated this word, Preacher, as Ecclesiastes and thus e titled the book. a. Ecclesiastes means Preacher; the Hebrew word “Koheleth” carries the menaing of preacher, teacher, or debater. b. The idea is that the message of Ecclesiastes is to be heralded throughout the world today. C. Ecclesiastes was written by Solomon. 1. Jewish tradition states Solomon wrote three books of the Bible: a. Song of Solomon, in his youth b. Proverbs, in his middle age years c. Ecclesiastes, when he was old 2. Solomon’s authorship had been accepted as authentic, until, in the past few hundred years, the “higher critics” have attempted to place the book much later and attribute it to someone pretending to be Solomon. a. Their reasoning has to do with a few words they believe to be of a much later usage than Solomon’s time. b. The internal evidence, however, strongly supports Solomon as the author. i. Ecc. 1:1 He calls himself the son of David and King of Jerusalem ii. Ecc. 1:12 Claims to be King over Israel in Jerusalem” iii. Only Solomon ruled over all Israel from Jerusalem; after his reign, civil war split the nation. Those in Jerusalem ruled over Judah. -

The Futility of Life Ecclesiastes 1:1-11

Ecclesiastes: The Futility of Life Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 February 21, 2016 Steve DeWitt We are beginning a new teaching series this weekend on the most intriguing book of the Bible. It’s not often preached through and I’ll bet few here have gone through a teaching series in it. So this will likely be brand new for most of us. That adds some excitement, doesn’t it? Today we begin Ecclesiastes. It’s found in the Old Testament, right after Proverbs and right before Song of Solomon. Right between wisdom and love. That’s appropriate given the questions Ecclesiastes raises about the meaning of life. If we were to take a tour of the Bible, when we arrived at Job our tour guide would say, “And now we’re entering the Wisdom literature.” This literary designation includes Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Solomon. These books are some of the most beautifully written in all of Scripture. They deal with life as it actually is. Job loses everything except his faith. Psalms sings through life’s ups and downs. Proverbs urges us away from folly and toward a practical life of wisdom. Then we get to Ecclesiastes. This book is enigmatic. It is embraced by philosophers and artists because of its gritty approach to the brevity of life. To give you an idea, here is a compiled list of the most used words in the book (Douglas Sean O’Donnell, Ecclesiastes: Reformed Expository Commentary, p. 10): Vanity (38) Wisdom (53) God (40) Toil (33) Death (21) Under the Sun (33) Joy (17) On the surface, its tone and questions seem rather gloomy. -

Ten Top Biblical Archaeology Discoveries

Ten Top Biblical Archaeology Discoveries Cover © 2011 Biblical Archaeology Society 1 Ten Top Biblical Archaeology Discoveries Ten Top Biblical Archaeology Discoveries Production and Design Staff: Joey Corbett – Editor Robert Bronder – Designer Susan Laden – Publisher © 2011 Biblical Archaeology Society 4710 41st Street, NW Washington, DC 20016 www.biblicalarchaeology.org © 2011 Biblical Archaeology Society i Ten Top Biblical Archaeology Discoveries About the Biblical Archaeology Society The excitement of archaeology and the latest in Bible scholarship since 1974 The Biblical Archaeology Society (BAS) was founded in 1974 as a nonprofit, nondenominational, educational organization dedicated to the dissemination of information about archaeology in the Bible lands. BAS educates the public about archaeology and the Bible through its bi-monthly magazine, Biblical Archaeology Review, an award-winning Web site (www.biblicalarchaeology.org), books and multimedia products (DVDs, CD-ROMs and videos), tours and seminars. Our readers rely on us to present the latest that scholarship has to offer in a fair and accessible manner. BAS serves as an important authority and as an invaluable source of reliable information. Publishing Excellence BAS’s flagship publication is Biblical Archaeology Review. BAR is the only magazine that connects the academic study of archaeology to a broad general audience eager to understand the world of the Bible. Covering both the Old and New Testaments, BAR presents the latest discoveries and controversies in archaeology with breathtaking photography and informative maps and diagrams. BAR’s writers are the top scholars, the leading researchers, the world- renowned experts. BAR is the only nonsectarian forum for the discussion of Biblical archaeology. BAS produced two other publications, Bible Review from 1985–2005, and Archaeology Odyssey from 1998–2006. -

Ezekiel 47:13-23 NASB Large Print Commentary

International Bible Lessons Commentary Ezekiel 47:13-23 New American Standard Bible International Bible Lessons Sunday, November 23, 2014 L.G. Parkhurst, Jr. The International Bible Lesson (Uniform Sunday School Lessons Series) for Sunday, November 23, 2014, is from Ezekiel 47:13-23. Questions for Discussion and Thinking Further follow the verse-by- verse International Bible Lesson Commentary below. Study Hints for Thinking Further, a study guide for teachers, discusses the five questions below to help with class preparation and in conducting class discussion; these hints are available on the International Bible Lessons Commentary website. The weekly International Bible Lesson is usually posted each Saturday before the lesson is scheduled to be taught. International Bible Lesson Commentary Ezekiel 47:13-23 (Ezekiel 47:13) Thus says the Lord GOD, “This shall be the boundary by which you shall divide the land for an inheritance among the twelve tribes of Israel; Joseph shall have two portions. 2 In Ezekiel 47:13-20, Ezekiel received instructions on how the Promised Land should be divided among the 12 tribes after they returned from exile. The Levites received some cities, a portion of the offerings, and lived among the other 12 tribes: Joseph’s descendants had been divided into two tribes, leaving 12 tribes to inherit the land. Since the returning exiles did not obey the vision that God gave Ezekiel, they did not divide the land according to Ezekiel’s vision either. (Ezekiel 47:14) “You shall divide it for an inheritance, each one equally with the other; for I swore to give it to your forefathers, and this land shall fall to you as an inheritance. -

Ecclesiastes – “It’S ______About _____”

“DISCOVERING THE UNREAD BESTSELLER” Week 18: Sunday, March 25, 2012 ECCLESIASTES – “IT’S ______ ABOUT _____” BACKGROUND & TITLE The Hebrew title, “___________” is a rare word found only in the Book of Ecclesiastes. It comes from a word meaning - “____________”; in fact, it’s talking about a “_________” or “_________”. The Septuagint used the Greek word “__________” as its title for the Book. Derived from the word “ekklesia” (meaning “assembly, congregation or church”) the title again (in the Greek) can simply be taken to mean - “_________/_________”. AUTHORSHIP It is commonly believed and accepted that _________authored this Book. Within the Book, the author refers to himself as “the son of ______” (Ecclesiastes 1:1) and then later on (in Ecclesiastes 1:12) as “____ over _____ in Jerusalem”. Solomon’s extensive wisdom; his accomplishments, and his immense wealth (all of which were God-given) give further credence to his work. Outside the Book, _______ tradition also points to Solomon as author, but it also suggests that the text may have undergone some later editing by _______ or possibly ____. SNAPSHOT OF THE BOOK The Book of Ecclesiastes describes Solomon’s ______ for meaning, purpose and satisfaction in life. The Book divides into three different sections - (1) the _____ that _______ is ___________ - (Ecclesiastes 1:1-11); (2) the ______ that everything is meaningless (Ecclesiastes 1:12-6:12); and, (3) the ______ or direction on how we should be living in a world filled with ______ pursuits and meaninglessness (Ecclesiastes 7:1-12:14). That last section is important because the Preacher/Teacher ultimately sees the emptiness and futility of all the stuff people typically strive for _____ from God – p______ – p_______ – p________ - and p________.