Synthesizing Zhenshi (Authenticity) and Shizhan (Combativity) Reinventing Chinese Kung Fu in Donnie Yen’S Ip Man Series (2008-2015) WAYNE WONG

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bamcinématek Presents a Brand New 40Th Anniversary Restoration of Robert Clouse’S Enter the Dragon, Starring Bruce Lee, in a Week-Long Run, Aug 30—Sep 5

BAMcinématek presents a brand new 40th anniversary restoration of Robert Clouse’s Enter the Dragon, starring Bruce Lee, in a week-long run, Aug 30—Sep 5 Series sidebar features five wing chun classics including Sammo Hung’s The Prodigal Son, Chang Cheh’s Invincible Shaolin, and Bruce Lee’s The Way of the Dragon, beginning Aug 29 “Bruce Lee was the Fred Astaire of martial arts.”—Pauline Kael, The New Yorker The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Brooklyn, NY/Aug 7, 2013—From Friday, August 30 through Thursday, September 5, BAMcinématek presents a week-long run of Robert Clouse’s Enter the Dragon, screening in a new DCP restoration for its 40th anniversary. In conjunction with the release of Wong Kar-wai’s Ip Man biopic The Grandmaster, this series revels in the lightning-fast moves of the revered kung fu tradition known as wing chun, featuring a five-film sidebar of martial arts rarities. Passed on through generations of martial artists, wing chun was popularized by icons like Sammo Hung and Ip’s movie-star disciple Bruce Lee—and has become an action movie mainstay. The first Chinese martial arts movie to be produced by a major Hollywood studio, Clouse’s Enter the Dragon features Bruce Lee in his final role before his untimely death (just six days before the film’s theatrical release). Shaolin master Mr. Lee (Lee) is recruited to infiltrate the island of sinister crime lord Mr. Han by going undercover as a competitor in a kung fu tournament. -

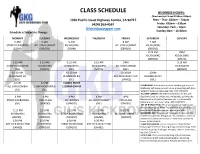

Class Schedule

CLASS SCHEDULE BUSINESS HOURS: (Wednesdays Closed 1130am-330pm) 1930 Pacific Coast Highway Lomita, CA 90717 Mon – Thur: 830am – 730pm (424) 263-4567 Friday: 830am – 630pm Saturday: 7am – 12pm Gilskickboxinggym.com Sunday: 8am – 10:30am Schedule is Subject to Change. MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 6 AM 6 AM 6 AM 6 AM 7 AM STRAP KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KICKBOXING (JOHN) (SERGIO) (JOHN) (SERGIO) (SERGIO) 8:15 AM 8AM KICKBOXING KICKBOXING (SERGIO) (MAYA) 9:15 AM 9:15 AM 9:15 AM 9:15 AM 9AM 9:15 AM STRAP KICKBOXING KICKBOXING KICKBOXING KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KICKBOXING (GIL) (MAYA) (GIL) (MAYA) (GIL) (SERGIO) 10:30 AM 10:30 AM 10:30AM 10AM BEGINNERS BJJ BEGINNERS BJJ ART OF 8 MUAY THAI BEGINNERS BJJ (GIL) (GIL) (JAMES) (GIL) 12 PM 12 PM CLOSED FROM KICKBOXING: A 60-minute workout combining a series of ALL GYM COMBAT STRAP KICKBOXING 1130AM-330PM kickboxing techniques you will do on a heavy bag with body (Gil) (GIL) weight muscle endurance exercises. (NO CONTACT) ALL GYM COMBAT: We use the whole gym for this one. 4 PM 4 PM 4 PM 4 PM 4PM Equipment such as battle ropes, Kettlebells, agility ladder, Bungee cable, Grappling Dummies, etc. combined with STRAP KICKBOXING KIDS CLASS KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KIDS CLASS Kickboxing to train like a fighter. (NO CONTACT) (GIL) (SERGIO) (SERGIO) (GIL) (SERGIO) ART OF 8 MUAY THAI: This Class focuses on teaching you the fundamentals of Muay Thai Kickboxing. You will learn 5:15 PM 5:15 PM 5:15 PM 5:15 PM 5:15PM how to hold Thai pads and gain real striking skills. -

Spectacle Theater

SUN MON TUES Wed thurs fri SAT 1 2 3 4 5 SPECTACLE 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 5:00 PROTECTORS OF THE Queen of burlesque THE PINK EGG EAT MY DUST LADY OF BURLESQUE UNIVERSE Director Q&A! 7:30 10:00 10:00 10:00 FLASH FUTURE KUNG FU SPACE THUNDER KIDS HARD BASTARD 10:00 LITTLE MAD GUY 10:00 LADY OF BURLESQUE DArnA VS. THE PLANET WOMEN Midnight HERCULES UNCHAINED Midnight THE HORROR OF SPIDER ISLAND 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 5:00 blood brunch the pink egg Solar adventure dog day pizza, birra, Faso flash future kung fu lady of burlesque 5:00 7:30 keep cool 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:00 darna vs. the planet lost & forgotten cinema little mad guy space transformer eat my dust protectors of the space thunder kids women 7:30 universe Contemporary underground • special events Queen of burlesque 10:00 Midnight hard bastard the horror of spider island Midnight I.K.U. 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 3:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 & 10:00 5:00 fist church hard bastard pizza, birra, Faso Queen of burlesque dog day silent lovers yeast ONE NIGHT ONLY! 5:00 7:30 the pink egg 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:00 8Ball tv space transformer keep cool darna vs. the planet solar adventure Midnight ONE NIGHT ONLY! 7:30 women the horror of spider eat my dust island 10:00 little mad guy Midnight hercules unchained 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 3:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 5:00 blood brunch solar adventure MATCH CUTS PRESENTS Queen of burlesque eat my dust keep cool space transformer ONE NIGHT ONLY! 5:00 7:30 flash future kung fu 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:00 space thunder kids dog day I.K.U hard bastard YEAST the pink egg 7:30 10:00 space thunder kids I.K.U. -

The Death of Dueling Wade Ellett

59 60 The Death of Dueling feuds, and a chivalric code of honor emphasizing virtue.6 Eventually this code of honor evolved into the upper class and nobility’s theory of courtesy and the idea of the “gentleman”. This resulted in the adoption of one-on-one combat to settle affairs in 7 the sixteenth century. The duel of honor, as recognized from entertainment media, was based primarily on the Italian Wade Ellett Renaissance idea of the gentleman and arrived in England in the 1570s.8 The practice was welcomed by the upper classes, who had Violence in some form or another has probably always long been awaiting a method to solve disputes. But the warm existed. Civilization did not end violence, it merely provided a reception was not shared by royalty, and Queen Elizabeth I framework to ritualize and institutionalize violent acts. Once outlawed the judicial duel in 1571.9 Her attempts to remove the civilized, ritual violence became almost entirely a man’s realm.1 practice from England failed and dueling quickly gained Ritual violence took many forms; but, without a doubt, one of the popularity.10 most romanticized was the duel. Dueling differed from wartime Dueling thrived in England for nearly three centuries; violence and barroom brawls because dueling placed two however, the practice eventually came to an end in 1852, when the opponents, almost always of similar social class, against one last recorded English duel was fought. There were many another in a highly stylized form of combat.2 Fisticuffs and war contributing factors to the practice’s end. -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

Donnie Yen's Kung Fu Persona in Hypermedia

Studies in Media and Communication Vol. 4, No. 2; December 2016 ISSN 2325-8071 E-ISSN 2325-808X Published by Redfame Publishing URL: http://smc.redfame.com Remediating the Star Body: Donnie Yen’s Kung Fu Persona in Hypermedia Dorothy Wai-sim Lau1 113/F, Hong Kong Baptist University Shek Mun Campus, 8 On Muk Street, Shek Mun, Shatin, Hong Kong Correspondence: Dorothy Wai-sim Lau, 13/F, Hong Kong Baptist University Shek Mun Campus, 8 On Muk Street, Shek Mun, Shatin, Hong Kong. Received: September 18, 2016 Accepted: October 7, 2016 Online Published: October 24, 2016 doi:10.11114/smc.v4i2.1943 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.11114/smc.v4i2.1943 Abstract Latest decades have witnessed the proliferation of digital media in Hong Kong action-based genre films, elevating the graphical display of screen action to new levels. While digital effects are tools to assist the action performance of non-kung fu actors, Dragon Tiger Gate (2006), a comic-turned movie, becomes a case-in-point that it applies digitality to Yen, a celebrated kung fu star who is famed by his genuine martial dexterity. In the framework of remediation, this essay will explore how the digital media intervene of the star construction of Donnie Yen. As Dragon Tiger Gate reveals, technological effects work to refashion and repurpose Yen’s persona by combining digital effects and the kung fu body. While the narrative of pain and injury reveals the attempt of visual immediacy, the hybridized bodily representation evokes awareness more to the act of representing kung fu than to the kung fu itself. -

Download Article

6th International Conference on Social Network, Communication and Education (SNCE 2016) The Development and Reflection on the Traditional Martial Arts Culture Zhenghong Li1, a and Zhenhua Guo1, b 1College of Sports Science, Jishou University Renmin South Road 120, Jishou City Hunan Province, China [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: Martial arts; Martial arts culture; Development; Reflection Abstract. Martial arts is an outstanding spiritual creation through the historical choice. As a kind of cultural form, it cnnotations. In this paper, using the research methods of literature, logic reasoning and so on, the interontains the rich cultural copretation of the traditional martial arts culture has been researched. The results show that The Chinese classical philosophy is the thought origin of the martial arts culture. Worshiping martial arts and advocating moral character are the important connotation of Chinese wushu culture. On the pre - qin period, contention of a hundred schools of thought in the field of ideology and culture make martial arts begin showing the cultural characteristics. The secularization of Song-Ming Neo-Confucianism makes martial arts gradually develop into a mature culture carrier. At the same time, this paper also analyzes the external martial arts’ impact on Chinese wushu; Western physical education’ misreading on Chinese wushu culture; The helpless of Chinese Wushu in In an age of extravagance and waste; The "disenchantment" of Chinese wushu culture in modern society; the condition and hope of Chinese martial arts culture. In view of this, this article calls for China should take great effort to study martial arts, refine, package and promote Chinese Wushu. -

Portfolio Investment Opportunities in China Democratic Revolution in China, Was Launched There

Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Investment Strategy The Great Wall of China In c. 220 BC, under Qin Shihuangdi (first emperor of the Qin dynasty), sections of earlier fortifications were joined together to form a united system to repel invasions from the north. Construction of the Great Wall continued for more than 16 centuries, up to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), National Emblem of China creating the world's largest defense structure. Source: About.com, travelchinaguide.com. The design of the national emblem of the People's Republic of China shows Tiananmen under the light of five stars, and is framed with ears of grain and a cogwheel. Tiananmen is the symbol of modern China because the May 4th Movement of 1919, which marked the beginning of the new- Portfolio Investment Opportunities in China democratic revolution in China, was launched there. The meaning of the word David M. Darst, CFA Tiananmen is “Gate of Heavenly Succession.” On the emblem, the cogwheel and the ears of grain represent the working June 2011 class and the peasantry, respectively, and the five stars symbolize the solidarity of the various nationalities of China. The Han nationality makes up 92 percent of China’s total population, while the remaining eight percent are represented by over 50 nationalities, including: Mongol, Hui, Tibetan, Uygur, Miao, Yi, Zhuang, Bouyei, Korean, Manchu, Kazak, and Dai. Source: About.com, travelchinaguide.com. Please refer to important information, disclosures, and qualifications at the end of this material. Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Investment Strategy Table of Contents The Chinese Dynasties Section 1 Background Page 3 Length of Period Dynasty (or period) Extent of Period (Years) Section 2 Issues for Consideration Page 65 Xia c. -

Sword Fighting : a Manual for Actors & Directors Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SWORD FIGHTING : A MANUAL FOR ACTORS & DIRECTORS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Keith Ducklin | 192 pages | 01 May 2001 | Applause Theatre Book Publishers | 9781557834591 | English | New York, United States Sword Fighting : A Manual for Actors & Directors PDF Book Sportsmanship, Hook. Fencing techniques, The Princess Bride. Today, I'll be breaking down clips from movies and T. List of styles History Timeline Hard and soft. Cheng Man-Ch'ing Mercenary Sword. By Yang, Jwing-Ming. Afterword by John Stevens. Very dead. Half-speed doesn't mean half-fighting. Come and Fence with us! By Dorothy A. Boken Japanese wooden sword , Budo Way of Warrior. Come on, then! The broadsword was notable for its large hilt which allowed it to be wielded with both hands due to its size and weight. It was originally a short sword forged by the Elves, but made for a perfect weapon for Hobbits. Explanation in Mandarin by Yang Zhengduo. A Swordsmith and His Legacy. But what he's doing is a lot of deflecting parries that are happening, so as an attack's coming in he's moving out of the way and deflecting the energy of it so that's how he's able to go up against steel. What the Studio Did: The Movie was near completion when Dean passed away, in fact all of scenes were completed. Experiences and practice. Garofalo's E-mail. Generally more common in modern contemporary plays, after swords have gone out of style but also seen in older plays such as Shakespeare's Othello when Othello strangles Desdemona. With the sudden end of constant war, the samurai class slowly became unmoored. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The wuxia film is the oldest genre in the Chinese cinema that has remained popular to the present day. Yet despite its longevity, its history has barely been told until fairly recently, as if there was some force denying that it ever existed. Indeed, the genre was as good as non-existent in China, its country of birth, for some fifty years, being proscribed over that time, while in Hong Kong, where it flowered, it was gen- erally derided by critics and largely neglected by film historians. In recent years, it has garnered a following not only among fans but serious scholars. David Bordwell, Zhang Zhen, David Desser and Leon Hunt have treated the wuxia film with the crit- ical respect that it deserves, addressing it in the contexts of larger studies of Hong Kong cinema (Bordwell), the Chinese cinema (Zhang), or the generic martial arts action film and the genre known as kung fu (Desser and Hunt).1 In China, Chen Mo and Jia Leilei have published specific histories, their books sharing the same title, ‘A History of the Chinese Wuxia Film’ , both issued in 2005.2 This book also offers a specific history of the wuxia film, the first in the English language to do so. It covers the evolution and expansion of the genre from its beginnings in the early Chinese cinema based in Shanghai to its transposition to the film industries in Hong Kong and Taiwan and its eventual shift back to the Mainland in its present phase of development. Subject and Terminology Before beginning this history, it is necessary first to settle the question ofterminology , in the process of which, the characteristics of the genre will also be outlined. -

Recommended Reading

RECOMMENDED READING The following books are highly recommended as supplements to this manual. They have been selected on the basis of content, and the ability to convey some of the color and drama of the Chinese martial arts heritage. THE ART OF WAR by Sun Tzu, translated by Thomas Cleary. A classical manual of Chinese military strategy, expounding principles that are often as applicable to individual martial artists as they are to armies. You may also enjoy Thomas Cleary's "Mastering The Art Of War," a companion volume featuring the works of Zhuge Liang, a brilliant strategist of the Three Kingdoms Period (see above). CHINA. 9th Edition. Lonely Planet Publications. Comprehensive guide. ISBN 1740596870 CHINA, A CULTURAL HISTORY by Arthur Cotterell. A highly readable history of China, in a single volume. THE CHINA STUDY by T. Colin Campbell,PhD. The most comprehensive study of nutrition ever conducted. ISBN 1-932100-38-5 CHINESE BOXING: MASTERS AND METHODS by Robert W. Smith. A collection of colorful anecdotes about Chinese martial artists in Taiwan. Kodansha International Ltd., Publisher. ISBN 0-87011-212-0 CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS TRAINING MANUALS (A Historical Survey) by Brian Kennedy and Elizabeth Guo CHRONICLES OF TAO, THE SECRET LIFE OF A TAOIST MASTER by Deng Ming-Dao. Harper San Francisco, Publisher ISBN 0-06-250219-0 (Note: This is an abridged version of a three- volume set: THE WANDERING TAOIST (Book I), SEVEN BAMBOO TABLETS OF THE CLOUDY SATCHEL (Book II), and GATEWAY TO A VAST WORLD (Book III)) CLASSICAL PA KUA CHANG FIGHTING SYSTEMS AND WEAPONS by Jerry Alan Johnson and Joseph Crandall.