Chapter 6 Bhutan, Myanmar and Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bhutan Green Growth Policy Note 7.31.14

July 31, 2014 Note on Green Growth for Bhutan Document of the World Bank 0 Table of Contents Introduction: What is the role for “green growth” in Bhutan? ....................................................... 5 Hydropower .................................................................................................................................... 9 Forestry ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Agriculture .................................................................................................................................... 18 Mining and Manufacturing ........................................................................................................... 22 Tourism ......................................................................................................................................... 27 Urbanization, Transportation and Environmental Challenges ...................................................... 29 Conclusions ................................................................................................................................... 32 Bibliography ................................................................................................................................. 35 Annex 1 –Funding for Climate Change and Environment .............................................................. i List of Boxes Box 1: Bhutan’s Macroeconomic Background .............................................................................. -

Burma's Long Road to Democracy

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Priscilla Clapp A career officer in the U.S. Foreign Service, Priscilla Clapp served as U.S. chargé d’affaires and chief of mission in Burma (Myanmar) from June 1999 to August 2002. After retiring from the Foreign Service, she has continued to Burma’s Long Road follow events in Burma closely and wrote a paper for the United States Institute of Peace entitled “Building Democracy in Burma,” published on the Institute’s Web site in July 2007 as Working Paper 2. In this Special to Democracy Report, the author draws heavily on her Working Paper to establish the historical context for the Saffron Revolution, explain the persistence of military rule in Burma, Summary and speculate on the country’s prospects for political transition to democracy. For more detail, particularly on • In August and September 2007, nearly twenty years after the 1988 popular uprising the task of building the institutions for stable democracy in Burma, public anger at the government’s economic policies once again spilled in Burma, see Working Paper 2 at www.usip.org. This into the country’s city streets in the form of mass protests. When tens of thousands project was directed by Eugene Martin, and sponsored by of Buddhist monks joined the protests, the military regime reacted with brute force, the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention. beating, killing, and jailing thousands of people. Although the Saffron Revolution was put down, the regime still faces serious opposition and unrest. -

Macroeconomic Trends and Policy Implications: Evidence from Bhutan

and health Macroeconomic Trends and Policy Implications: Evidence from Bhutan Mashrur Khan and Matthew Robson * 1. Introduction Bhutan has performed remarkably well with an average growth rate of 7.72 percent from 2004-2014. This growth is heavily fuelled by its strong hydropower sector, particularly the exports of hydropower, which have grown at an average rate of 18.1 percent over the same period. In recent years, hydropower capacity has been increased substantially, leading to higher exports and electricity generation in the country. In addition, the tourism sector has grown rapidly over the last decade, which largely contributed to the generation of revenue for the country. Despite these successes, the country has experienced some setbacks, particularly in recent years. The current account deficit has been on the rise, which was mainly due to increasing hydropower-related imports to facilitate the installation of new hydropower plants. In addition, rapid credit growth has led to a consumption and housing boom, which contributed to large non-hydropower related imports. Consequently, the total reserves for the country as a percentage of total external debt has declined - reducing their ability to service debt - which is concerning since their external debt as a ratio of GDP has risen to over 80 percent in 2013-14 from around 55 percent in 2007- 08. This paper focuses on the macroeconomic trends that Bhutan has experienced since the 1990s. The paper provides detailed graphs and tables on selected economic indicators, particularly on the budget, inflation and balance of payment estimates for the country. However, the data available from various sources * Department of Economics and Related Studies, University of York, York, UK We would like to extend our appreciation to Sabina Alkire, at the OPHI, for her support throughout. -

The Case of Bhutan

Food Sec. DOI 10.1007/s12571-017-0647-5 ORIGINAL PAPER The importance and challenges of crop germplasm interdependence: the case of Bhutan Mahesh Ghimiray1 & Ronnie Vernooy2 Received: 25 January 2016 /Accepted: 2 January 2017 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract An analysis of food crop germplasm flows into and Keywords Biodiversity . Crop germplasm . Food security . out of Bhutan was carried out to determine the extent of reli- Interdependence . Multilateral system . Pedigree analysis ance of Bhutanese agriculture on introduced germplasm. Methods used included literature review, key informant inter- views, field visits and crop pedigree analysis. Bhutan has been Introduction introducing foreign germplasm since the 1960s. By December 2015, about 300 varieties of 46 food crops including several No country in the world is self-sufficient in germplasm to non-traditional crops were introduced. Germplasm sources fulfill its food requirements. Most major agricultural crops include CGIAR centres such as IRRI, CIMMYT, ICARDA, evolved over a period of thousands of years in the developing and AVRDC and countries such as Bangladesh, India, Japan, countries which have the greatest concentration of genetic Korea, Nepal, and Thailand. Pedigree analysis of rice varieties diversity. Many countries heavily depend on non-indigenous indicated that 74% of the released varieties originated in other crops and imported germplasm for food and agricultural countries. Using imported germplasm, Bhutan has formally development (Fowler et al. 2000). Today, all countries and released over 180 varieties of cereals, fruits and vegetables. all regions have become highly interdependent (Galluzzi Initially, the germplasm flow was largely unregulated, but the et al. -

Impact of Cross-Border Electricity Trade on Bhutan (Country Series)

SOUTH ASIA REGIONAL INITIATIVE FOR ENERGY INTEGRATION (SARI/EI) Working Paper: Impact of Cross-Border Electricity Trade on Bhutan (Country Series) September, 2016 IRADe-SARI/EI-WP-2016-01 Report Prepared by: Mr. Gaurav Jain, Senior Research Analyst Mr. Vinay Kumar Saini, Senior Research Analyst SARI/EI Team, IRADe Disclaimer This study is made possible by the support of American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this study do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Integrated Research and Action for Development (IRADe) does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. SOUTH ASIA REGIONAL INITIATIVE FOR ENERGY INTEGRATION (SARI/EI) Working Paper: Impact of Cross-Border Electricity Trade on Bhutan (Country Series) September, 2016 Contents List of Abbreviations ..............................................................................................................v Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................... vii Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. ix 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................01 2. Bhutan’s Power Sector ....................................................................................................04 -

Foreign Trade in Bhutan

Chapter-6 Foreign Trade in Bhutan • Introduction • Bhutan's Trade Policy Initiatives • Trade Patterns in Bhutan • Bhutan's Trade Pattern with India • Bhutan's Trade with Countries other Than India • Bhutan's Overall Trade Pattem • External Trade and Environmental Linkages in Bhutan • Conclusion • Reference 6.1: Introduction The economy of Bhutan is regarded as a closed economy and characterized by extreme isolationism from the rest of the world. A careful probe into the history of the country however shows that the country did have trade relations with neibouring countries like India (Bengal & Assam) and Tibet even in the medieval period. However, there is no denying the fact that foreign trade of Bhutan was constrained by some genuinely prohibitive factors viz. landlockness of the country, prevailing barter economic system, existence of self-sufficient communities producing petty marketable surplus as well as its non-colonial regime. Bhutan's foreign trade was traditionally confined to a few basic essential commodities like salt, soda, kerosene, tea etc. and was not governed by laws of the comparative advantage. However, this trade helped economic development of the country from various aspects of development. This pattern of trade continued up to late 1950s. All this has been discussed in chapter-2 of this dissertation. It was only after the introduction of its planned development regime m 1961 that Bhutan's foreign trade gradually diversified both in terms of commodities as well as trading partners. Even at the beginning of its planned economic development, Bhutan exported a few primary products to its southern neighbours, the northern trade being closed for the Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1958. -

The Production of Bhutan's Asymmetrical Inbetweenness in Geopolitics Kaul, N

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch 'Where is Bhutan?': The Production of Bhutan's Asymmetrical Inbetweenness in Geopolitics Kaul, N. This journal article has been accepted for publication and will appear in a revised form, subsequent to peer review and/or editorial input by Cambridge University Press in the Journal of Asian Studies. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © Cambridge University Press, 2021 The final definitive version in the online edition of the journal article at Cambridge Journals Online is available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911820003691 The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Manuscript ‘Where is Bhutan?’: The Production of Bhutan’s Asymmetrical Inbetweenness in Geopolitics Abstract In this paper, I interrogate the exhaustive ‘inbetweenness’ through which Bhutan is understood and located on a map (‘inbetween India and China’), arguing that this naturalizes a contemporary geopolitics with little depth about how this inbetweenness shifted historically over the previous centuries, thereby constructing a timeless, obscure, remote Bhutan which is ‘naturally’ oriented southwards. I provide an account of how Bhutan’s asymmetrical inbetweenness construction is nested in the larger story of the formation and consolidation of imperial British India and its dissolution, and the emergence of post-colonial India as a successor state. I identify and analyze the key economic dynamics of three specific phases (late 18th to mid 19th centuries, mid 19th to early 20th centuries, early 20th century onwards) marked by commercial, production, and security interests, through which this asymmetrical inbetweenness was consolidated. -

Japan's Development Cooperation

Acknowledgement I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to IDE-JETRO for providing me the opportunity to carry out my research for six months as a visiting research fellow. I am thankful to Tatsufumi Yamagata-san, Director General of International Exchange and Training Department for his profound advice and support. I owe my debt of gratitude to Shozo Sakata-san, my supervisor, for his valuable guidance and advice on my research. I remain thankful to Takeo Masuda-san, Atsuko Hirakata-san and Kumi Manda-san for their help and kind support in ensuring that my research activities were in order. I would also like to appreciate the efficient services rendered by a team of kind staff at the IDE-Library. My research immensely benefited from the interviews and interactions with Kitano Naohiro- san, Deputy Director at the JICA Research Institute, Suhara Yasuhiro-san, Deputy Director at the JICA headquarter, Asako Sakurai-san, Chief Director at JETRO headquarter, and Kenji Ishizuka-san at JETRO headquarter. I am deeply thankful to them. I would like to acknowledge that I have benefited from the interactions with fellow VRFs and other researchers at the IDE. My research also benefited from the feedback that I received during my research presentations. Finally, I would like apprise the readers that all the findings, interpretations and recommendations expressed in this research paper are solely of the author and do not imply the views of any government agency in Bhutan nor the IDE in Japan. -i- Contents Acknowledgement …………………………………………………………………………………………… i List of Figures …………………………………………………………………………………………… iv List of Tables ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… v List of Maps ………………………………………………………………………………………………… v List of Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………………………… vi Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………………… vii 1. -

Where to Spend the Next Million? Approaches to Addressing Constraints Faced by Developing Countries As They Seek to Benefit from the Gains from Trade

a “A welcome trend is emerging towards more clinical and thoughtful to Spend the Next Million? Where approaches to addressing constraints faced by developing countries as they seek to benefit from the gains from trade. But this evolving approach brings Where to Spend the Next with it formidable analytical challenges that we have yet to surmount. We need to know more about available options for evaluating Aid for Trade, Million? which interventions yield the highest returns, and whether experiences in one development area can be transplanted to another. These are some of the issues addressed in this excellent volume.” Applying Impact Evaluation to Pascal Lamy, Director-General, World Trade Organization Trade Assistance “Five years into the Aid for Trade project, we still need to learn much more about what works and what does not. Our initiatives offer excellent opportunities to evaluate impacts rigorously. That is the way to better connect aid to results. The collection of essays in this well-timed volume shows that the new approaches to evaluation that we are applying to Assistance Applyng Impact Evaluation to Trade education, poverty, or health programs can also be used to assess the results of policies to promote or assist trade. This book offers a valuable contribution to the drive to ensure value for aid money.” Robert Zoellick, President, The World Bank a THE WORLD BANK ISBN 978-1-907142-39-0 edited by Olivier Cadot, Ana M. Fernandes, Julien Gourdon and Aaditya Mattoo a THE WORLD BANK 9 781907 142390 WHERE TO SPEND THE NEXT MILLION? Where to Spend the Next Million? Applying Impact Evaluation to Trade Assistance Copyright © 2011 by The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA ISBN: 978-1-907142-39-0 All rights reserved The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank or the governments they represent. -

1. India and Myanmar: Understanding the Partnership – Sampa Kundu

MYANMAR AND SOUTH ASIA 1. India and Myanmar: Understanding the Partnership – Sampa Kundu, Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, New Delhi, India; PhD Candidate, School of International Studies, Jawarhalal Nehru University, New Delhi, India Abstract: India’s bilateral relations with Myanmar has raised both optimism and doubts because of a number of ups and downs which portray India’s vague willingness to remain favoured by the Myanmar government and Myanmar’s calculated desire to get advantages from its giant neighbours including India. Scholars and practitioners have explained many times why both India and Myanmar need each other. Some may call it a realist politics and some may call it a fire-brigade alarm politics which implies that both of them act according to the need of the time. The objective of this paper is to explain the necessities of India and Myanmar to each other and how they respond to each other in different times. Connectivity, security, energy and economy are four major pillars of Indo- Myanmar bilateral relationship. Hence, each of these four sectors would have their due share in the proposed paper to illustrate the present dynamics of Indo-Myanmar partnerships. Factors like US, China and the regional cooperation initiatives including ASEAN and BIMSTEC are the external factors that are most likely to shape the future of the Indo-Myanmar relationships. Hence, a simultaneous effort would also be taken to explain the extent of their influence on the same. Based on available primary and secondary literature and field trips, this account will help the readers to contextualise Indo-Myanmar relationship in the light of international relations. -

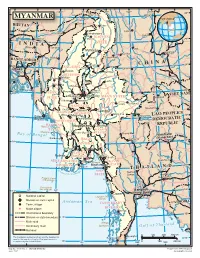

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

Economic History of Bhutan

Chapter-2 Economic History of Bhutan • Periodization of History • Economic History of Medieval Bhutan • Conclusion • Reference 2.1: Periodization of History Periodization of history is essential for a logically convenient and chronologically better understanding of the past and the present. Evidence from historical literature shows that the so-called periodization is a common practice in order to distinguish between different socio-cultural, political and economic attributes under distinct chronological time periods. It is a general practice to divide the history of a country into three distinct periods- Ancient, Medieval and Modem, each period covering separate time periods. Following the same methodology, history of Bhutan is also divided into Ancient, Medieval and Modem. It is to be noted that periodization of Bhutanese history does not tally with that of other countries. It is accepted that modern Bhutan emerged in the 1960s following Jawahar Lal Nehru's visit and inception of planned development1, while in other neibouring countries like India it began centuries earlier. One important phase of Bhutan's history started in 1625 when Sabdrung Namgayal unified the country and brought it under a single authority. The history of pre-Sabgrung Bhutan is full of legends and myths and no reliable or authentic documents are available for the concerned period, which has been termed as Ancient history ensued from the 5th or 6th century A.D. According to the oldest Bhutanese chronicles, no formal religion and government, administration and taxation, castism and mutual interests existed in Ancient Bhutan. Self-sufficient village communities were governed by the villages heads without any communication, market transactions and education facilities.