Finances Nation 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Active Transportation Strategy

ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION STRATEGY With more people using active transportation, the air will be cleaner, people will be healthier, and money will be saved. 2 For many residents of PEI, there are opportunities to incorporate active transportation into our day-to-day lives. The PEI Active Transportation Everyone has a role to play Strategy lays out pathways to in order to increase active support Islanders in making transportation on PEI. active, cleaner and healthier transportation choices. PEI ACTIVE 3 TRANSPORTATION STRATEGY For many residents of PEI, there are opportunities to incorporate active transportation into our day-to-day lives. The simple act of leaving the car at home and using muscle power for transportation, at least some of the time, will have a number of positive outcomes for individuals, communities and society. With more people using active transportation, the air will be cleaner, people will be healthier, and money will be saved. The PEI Active Transportation Strategy lays out pathways to support Islanders in making active, cleaner and healthier transportation choices. Through a variety of investments and outreach initiatives the strategy will focus on: • Enhancing the safety of everyone who uses active forms of transportation through infrastructure improvements; • Improving active transportation route connectivity within and among communities and between key destinations across the province; • Strengthening partnerships with municipalities, Indigenous communities and non-government organizations (NGOs) around walking, cycling and any other forms of active transportation; and • Creating a promotion and education campaign to increase the confidence and competence of those wanting to commute actively. While developing the Sustainable Transportation Action Plan for PEI, Islanders were asked what should be done to encourage more active transportation. -

(NCBR) Initiative Proposal Development & Reporting Guide

First Nations National Child Benefit Reinvestment (NCBR) Initiative Proposal Development & Reporting Guide This Guide has been developed by First Nations and INAC. Table of Contents Page Introduction iii Section A B The NCBR Proposal A B 1 How First Nations Can Access NCBR Funding 1 A B 2 Roles and Responsibilities 1 A B 3 Writing the Proposal 2 A B 4 Proposal Checklist 5 A B 5 Submitting the Proposal 5 A B 6 Proposal Template 7 Section B B Reporting B B 1 Timeframes for Reporting 9 B B 2 First Nations= NCB Annual Report on Reinvestment 9 Section C B Information on the NCBR Initiative C B 1 Introduction to the NCBR 12 C B 2 Objectives of the NCBR Initiative 12 C B 3 NCBR Activity Areas 13 C B 4 What is Not Eligible 15 Appendices Glossary of Terms 17 Frequently Asked Questions 19 Self-Evaluation 21 Resources 23 Sample Completed Proposal 24 Sample Participant Evaluation/Questionnaire 26 Sample Completed NCB Annual Report on Reinvestment 27 First Nations= NCBR Proposal Development & Reporting Guide ii INTRODUCTION The National Child Benefit initiative has been running since 1998 following the agreement of the federal, provincial and territorial Ministers of Social Services that governments, including First Nations, should work together to address the problem of child poverty in Canada. The First Nations= National Child Benefit Reinvestment (NCBR) initiative has been established as the on-reserve counterpart to provincial/territorial programs. The services and benefits are aimed at ensuring that First Nation children receive the best possible opportunity to develop fully their potential as healthy, active and contributing members of their communities. -

PEI Home and School Federation 2018 Annual Report

PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND HOME AND SCHOOL FEDERATION INC. Drawing by Jaden Grant Grade 9 East Wiltshire Intermediate School 65th Annual Meeting & Convention Book of Reports Saturday, April 14, 2018 Rodd Charlottetown Hotel 75 Kent Street, Charlottetown, P.E.I. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ......................................................................................................... 2 Mission Statement/Home and School Thought/Creed ................................................ 3 List of Federation Presidents 1953-2018 ..................................................................... 4 Agenda 2018 ................................................................................................................ 5 Business Procedure/Meeting Tips .............................................................................. 6 Federation Board Directory 2017-2018 ....................................................................... 7 Local Presidents/Co-Chairs Directory 2017-2018 ...................................................... 7 Annual General Meeting’s Minutes 2017 ................................................................... 9 Semi Annual Meeting’s Minutes 2017 ...................................................................... 20 President’s Annual Report ......................................................................................... 21 Executive Director Report ......................................................................................... 24 Financial Report ........................................................................................................ -

PEIANC 2017/2018 Annual Report

2017/2018 Annual Report 1 PEI Association for Newcomers to Canada Board of Directors 2017/2018 49 Water Street Julius Patkai, President Ali Assadi Julius Patkai Craig Mackie Charlottetown, PE C1A 1A3 Tina Saksida, Vice President Arnold Croken Phone: (902) 628-6009 Jim Hornby, Treasurer Joe Zhang President of the Board Executive Director Fax: (902) 894-4928 Kaitlyn Angus, Secretary Jolene Chan Email: [email protected] Laura Lee Howard It has been another successful We are in the midst of changing Website: www.peianc.com Rachel Murphy year and I am grateful to be Presi- times and while there are chal- Selvi Roy dent of the Board of the PEI Asso- lenges, there are opportunities ciation for Newcomers to Canada. as well. PEIANC appreciates the A special thank you goes out to continued funding support from Federal and Provincial funding all levels of government to sup- partners, as well as municipalities port newcomers to PEI. New ar- and donors, for their continued rivals, from 78 different countries, support of the Association. totalled 1,987 and included 1,310 I was once a newcomer to permanent residents, 640 tem- Canada, arriving in 1971 from a refugee camp in Italy. porary residents, and 37 others. The largest intake was I can relate to the difficulties one can encounter when from China, and we saw increasing numbers from India, entering a new country, a new home, a new way of life, Vietnam, and the Philippines. We also welcomed 132 and the challenges one faces when adapting to a new cul- refugees. I completed my two-year term as Co-Chair of ture. -

The Post-Welfare State in Canada: Income-Testing and Inclusion

The Post-Welfare State in Canada: Income-Testing and Inclusion by Ken Battle and Sherri Torjman May 2001 This Report was prepared for the Consortium for Economic Policy Research and Advice Project (CEPRA) “Living Standards and Income Inequality in Selected Regions” International and Canadian Programs Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada ISBN 1-894598-81-4 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Core Concepts in Canadian Social Policy 2 The ‘Why’ of Income Security 2 The ‘How’ of Income Security 4 a. Eligibility criteria 4 b. Income program design 6 i. Social insurances 6 ii. Tax-supported income programs 7 Universal programs 7 Income-tested programs 8 Needs-tested programs 9 c. Assessment of program design 9 Income Security Reform in Canada 11 The Universalist Model of Social Policy 13 Growth of the Universalist Welfare State 16 Building the Welfare State 16 Reality Versus Theory 19 Roots of Reform: Canadian Context 21 Economic Changes 21 Social Changes 22 Political Changes 23 Social Union Framework Agreement 25 Roots of Reform: International Context 27 Overhaul of Social Assistance and Child Benefits 29 Social Assistance 29 Child Benefits 32 The rise of income-tested targeting 33 Rationale for reform 34 Structural reform: The National Child Benefit 36 Objectives of reform 36 Progress 38 Criticisms 38 a. Treatment of social assistance families 39 b. The welfare wall is more than child benefits 41 c. The incentives issue: Marginal tax rates 41 d. Lack of responsiveness to changes in income 42 A work in progress 42 From Unemployment Insurance to Employment Insurance 44 Expansion 44 Retrenchment 44 Elderly Benefits: Uneasy Compromise between Universalist and Post-Welfare Models 47 A Mix of Direct and Tax-Delivered Programs 47 Reforms 49 a. -

Annual Report

Annual Report 2019-2020 What’s in this report Page • The Literacy Crisis 1 • Our Mission 2 • Year at a Glance (2019-2020) 3 • Ready Set Learn 4 • Free Books for Kids 5 • Adult Learner Awards 6 • Essential Skills for Atlantic Fisheries 7 • PGI Golf Tournament for Literacy 8 • Public Awareness 9 • Our Member Organizations 10 • Our Board of Directors 11 • Our Team 12 • Our Core Funder 13 The Literacy Crisis Literacy is a basic human right. 40% of kindergarten-aged children in PEI who completed the Early Years Evaluation did not meet the developmental milestones in at least one of the five skill areas. (2017 Children’s Report) 1200 Island children in grades K to 6 were referred to us by resource teachers this year because they were struggling with reading, writing and/or math. Note: This number is likely higher as we limit the number of referrals teachers can send in. 45% of working-aged Islanders don’t have the literacy skills needed to succeed in our digital world. (PIAAC 2012) We are determined to change these statistics 1 Our Mission We work to advance literacy for the people of Prince Edward Island We exist so that: • gaps and overlaps in literacy services will be decreased • barriers to people with low literacy levels will be reduced • Islanders will be better informed about the personal costs of low literacy on economic, cultural, political and social aspects of life • literacy will be valued and celebrated across PEI 2 Year at a Glance (2019-2020 Fiscal) Funding Secured $645,073 Because the Alliance existed this year: • 1198 children boosted their literacy skills, confidence, and learning attitudes • 1735 books were distributed to families • 11 adults gained literacy and employability skills and 8 were employed after the program • Thousands of Islanders are better informed about literacy in PEI 3 Since 2001 Ready Set Learn “I learned that if I try hard I can do it” grade 2 participant We ran our free summer tutoring program for the 19th year during the summer and school-year. -

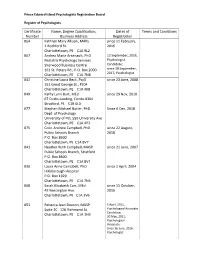

Certificate Number Name, Degree Qualification, Business Address

Prince Edward Island Psychologists Registration Board Register of Psychologists Certificate Name, Degree Qualification, Dates of Terms and Conditions Number Business Address Registration 064 Kathren Mary Allison, MAPs since 11 February, 1 Rochford St. 2016 Charlottetown, PE C1A 9L2 067 Andrea Marie Arsenault, PhD 13 September, 2016, Pediatric Psychology Services Psychologist Sherwood Business Centre Candidate; 161 St. Peters Rd., P.O. Box 2000 since 28 September, Charlottetown, PE C1A 7N8 2017, Psychologist 042 Christine Laura Beck, PsyD since 23 June, 2008 151 Great George St., #204 Charlottetown, PE C1A 4K8 049 Kathy Lynn Burt, MEd since 29 Nov, 2010 67 Ducks Landing, Condo #304 Stratford, PE C1B 0L3 077 Stephen Michael Butler, PhD Since 6 Dec, 2018 Dept. of Psychology University of PEI, 550 University Ave Charlottetown, PE C1A 4P3 075 Colin Andrew Campbell, PhD since 22 August, Public Schools Branch 2018 P.O. Box 8600 Charlottetown, PE C1A 8V7 041 Heather Ruth Campbell, MASP since 21 June, 2007 Public Schools Branch, Stratford P.O. Box 8600 Charlottetown, PE C1A 8V7 036 Laura Anne Campbell, PhD since 1 April, 2004 Hillsborough Hospital P.O. Box 1929 Charlottetown, PE C1A 7N5 068 Sarah Elizabeth Carr, MEd since 11 October, 49 Kensington Ave. 2016 Charlottetown, PE C1A 3V6 051 Rebecca Jean Deacon, MASP 5 April, 2011, Suite 2C 126 Richmond St. Psychological Associate Candidate; Charlottetown, PE C1A 1H9 30 May, 2011, Psychological Associate; since 16 June, 2016, Psychologist Prince Edward Island Psychologists Registration Board Register of Psychologists 025 Nadine Alison DeWolfe, PhD since 20 April, 1999 Sherwood Business Centre Pediatric Psychology Services P.O. -

RESP Dealers Association of Canada

RESP Dealers Association Of Canada Sales Representative Proficiency Course August 2007 RESP Dealers Association of Canada Sales Representative Proficiency Course FOREWORD These course materials have been prepared by the RESP Dealers Association of Canada as part of the Association’s ongoing effort to establish the highest standards of knowledge and conduct among those who distribute scholarship plans in Canada. This course includes materials from several sources. We would like to thank: • The members of the RESP Dealers Association of Canada • The British Columbia Securities Commission • The Canadian Securities Administrators • Canada Revenue Agency • Human Resources and Skills Development Canada • Ken Goodwin, C.A. • Dean Holley, CMC Capital Market Consulting Corp. These course materials are the property of the RESP Dealers Association of Canada and are not to be reproduced with prior permission. August 2007 1 RESP Dealers Association of Canada Sales Representative Proficiency Course TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................5 A. Who is this course for?....................................................5 B. What will be covered in the material................................6 C. The RESP Dealers Association of Canada .....................6 2. DEFINITIONS....................................................................8 3. CODE OF SALES PRACTICES......................................13 A. Purpose of the Code .....................................................13 B. Standards......................................................................14 -

Town of Stratford 2015 Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventory Ben Grieder

Town of Stratford 2015 Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventory Ben Grieder This document outlines the methodology, calculations results, quality control methods and the primary sources used to create the 2015 Greenhouse Gas Inventory for the Town of Stratford. The PCP Protocol: Canadian Supplement to International Emission Analysis Protocol was used as a guiding document throughout the creation of this Town of Stratford inventory. All required fields of data collection were completed along with some optional fields included in the 234 Shakespeare Avenue, Corporate Inventory. Appendix items included in this Stratford, PEI document will help guide the creation of future inventories 902- 5 6 9 - 1995 that occur in the Town of Stratford. 902- 5 6 9 - 5000 1 2 / 1 5 / 2 0 1 6 Contents List of Tables and Figures .............................................................................................................................. 2 Definitions ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Exceutive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Establishing Operational Boundaries ............................................................................................................ 7 Corporate Inventory ................................................................................................................................. 7 -

A State of the Art Review of Income Security Reform in Canada

IDRC tib. 4 0 i ao Working Series Paper #4 A State of the Art Review of Income Security Reform in Canada Jane Pulkingham Simon Fraser University and Gordon Ternowetsky University of Northern British Columbia This document is disseminated as part of a Working Paper Series of IDRC's Assessment of Social Policy Reforms (ASPR) Programme Initiative. ASPR draws on the knowledge and experience of a wide variety of experts. Documents made available through the Working Paper Series are intended to contribute to the debate around ASPR's areas of research. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the International Development Research Centre or ASPR. IDRC/CRDI Ottawa, Canada April, 1998 INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH CENTRE Ottawa / Cairo / Johannesburg / Montevideo / Nairobi / New Delhi / Singapore Ak.Gf r 3 t 2 "= 1 PREFACE A State of the Art Review: Income Security Reform in Canada INTRODUCTION In both the North and South today, in the context of broader social policy reform trends, increasing attention is being devoted to the revision of social security systems. Globalization, demographic shifts, employment trends and growing poverty underlie a re-examination of the capacity of these systems to protect the basic welfare of societies. Moreover, these reforms are occurring in the context of neo-liberal adjustment and conservative fiscal strategies. Whether in developing or OECD countries, social security systems-- encompassing pension programs, social assistance plans, income support programs and social transfers-- are being considered in light of growing concerns with the limited capacities of states, pre-occupations with affordability and sustainability, a preference for the allocative efficiency of the market, and ideologies which delegate greater responsibility for social welfare to communities and individuals. -

Popular Music in Elementary Programs Prince Edward Island Teachers’ Perspectives

Popular Music in Elementary Programs Prince Edward Island Teachers’ Perspectives by © Nicole Waite A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education (Curriculum, Teaching and Learning Studies) Faculty of Education Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2019 St. John’s Newfoundland Abstract This qualitative study investigates the perspectives of Prince Edward Island elementary music teachers on topics of popular music and teacher preparation in post-secondary education programs. In-depth interviews were completed with 10 elementary music teachers to investigate their views on the use of popular music in the elementary classroom, their personal definition of popular music, and barriers that they may have encountered when incorporating this style into their programming. Teachers were also asked about their experiences in post-secondary music education programs, what courses they found were most applicable to their current positions, and suggestions they may have for improvements to these programs. Keywords: Elementary music education, popular music, Prince Edward Island, teacher perspectives, interviews, grounded theory, post-secondary music education Acknowledgements I would like to extend a special thank-you to my thesis advisor, Dr. David Buley. His openness to a variety of views and his curiosity for new ideas allowed me to freely shape my inquiries. Also, I would like to thank Dr. June Countryman, who has been an inspiration to me since the beginning of my academic career and continues to donate her time generously in order to guide my questions and strengthen my arguments. Thanks to Dr. Andrea Rose for her encouragement and guidance, and to Dr. -

Ivities Date

Fall/Winter 2019 ACT UP PrinceIVITIES Edward Island Advisory Council onDATE the Status of Women NEW COUNCIL CHAIRPERSON’S MESSAGE: CHAIRPERSON DEBBIE LANGSTON The PEI Advisory I am honoured to be appointed as Council on the Chairperson of the PEI Advisory Status of Women is Council on the Status of Women, and very pleased that I am looking forward to undertaking the Government the work, pushing forward with our of Prince message, and advocating for gender Edward Island equality for all Islanders. has appointed Debbie Langston of I am happy my appointment Blooming Point to chair the Council comes in time to lead the Purple from October 2019 to the end of her Ribbon Campaign Against Violence term in March 2021. Debbie previously Against Women, as we prepare served as Vice-Chairperson. for a meaningful December 6th Debbie and her sisters were raised Montreal Massacre Memorial Service by their mother in the UK. After to commemorate 30 years since leaving school, Debbie worked for the 14 women lost their lives at l’Ecole Metropolitan Police Service, where Polytechnique, just because they were she met her husband Robin. They women. immigrated to Canada with their young I am likewise looking forward to family in 2004. Debbie graduated from meeting four newly appointed Council the Holland College Child and Youth members who will join us at the table. Care Worker course in 2009 and is currently enrolled in the Bachelor of I would like to thank Council staff, Jane, Arts program at UPEI. She has worked Michelle, and Becky, and all the women in a variety of settings and is currently who served on the Council this past employed as a Youth Service Worker year for a successful year of advising with the Public Schools Branch.