Popular Music in Elementary Programs Prince Edward Island Teachers’ Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Active Transportation Strategy

ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION STRATEGY With more people using active transportation, the air will be cleaner, people will be healthier, and money will be saved. 2 For many residents of PEI, there are opportunities to incorporate active transportation into our day-to-day lives. The PEI Active Transportation Everyone has a role to play Strategy lays out pathways to in order to increase active support Islanders in making transportation on PEI. active, cleaner and healthier transportation choices. PEI ACTIVE 3 TRANSPORTATION STRATEGY For many residents of PEI, there are opportunities to incorporate active transportation into our day-to-day lives. The simple act of leaving the car at home and using muscle power for transportation, at least some of the time, will have a number of positive outcomes for individuals, communities and society. With more people using active transportation, the air will be cleaner, people will be healthier, and money will be saved. The PEI Active Transportation Strategy lays out pathways to support Islanders in making active, cleaner and healthier transportation choices. Through a variety of investments and outreach initiatives the strategy will focus on: • Enhancing the safety of everyone who uses active forms of transportation through infrastructure improvements; • Improving active transportation route connectivity within and among communities and between key destinations across the province; • Strengthening partnerships with municipalities, Indigenous communities and non-government organizations (NGOs) around walking, cycling and any other forms of active transportation; and • Creating a promotion and education campaign to increase the confidence and competence of those wanting to commute actively. While developing the Sustainable Transportation Action Plan for PEI, Islanders were asked what should be done to encourage more active transportation. -

PEI Home and School Federation 2018 Annual Report

PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND HOME AND SCHOOL FEDERATION INC. Drawing by Jaden Grant Grade 9 East Wiltshire Intermediate School 65th Annual Meeting & Convention Book of Reports Saturday, April 14, 2018 Rodd Charlottetown Hotel 75 Kent Street, Charlottetown, P.E.I. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ......................................................................................................... 2 Mission Statement/Home and School Thought/Creed ................................................ 3 List of Federation Presidents 1953-2018 ..................................................................... 4 Agenda 2018 ................................................................................................................ 5 Business Procedure/Meeting Tips .............................................................................. 6 Federation Board Directory 2017-2018 ....................................................................... 7 Local Presidents/Co-Chairs Directory 2017-2018 ...................................................... 7 Annual General Meeting’s Minutes 2017 ................................................................... 9 Semi Annual Meeting’s Minutes 2017 ...................................................................... 20 President’s Annual Report ......................................................................................... 21 Executive Director Report ......................................................................................... 24 Financial Report ........................................................................................................ -

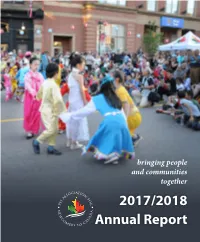

PEIANC 2017/2018 Annual Report

2017/2018 Annual Report 1 PEI Association for Newcomers to Canada Board of Directors 2017/2018 49 Water Street Julius Patkai, President Ali Assadi Julius Patkai Craig Mackie Charlottetown, PE C1A 1A3 Tina Saksida, Vice President Arnold Croken Phone: (902) 628-6009 Jim Hornby, Treasurer Joe Zhang President of the Board Executive Director Fax: (902) 894-4928 Kaitlyn Angus, Secretary Jolene Chan Email: [email protected] Laura Lee Howard It has been another successful We are in the midst of changing Website: www.peianc.com Rachel Murphy year and I am grateful to be Presi- times and while there are chal- Selvi Roy dent of the Board of the PEI Asso- lenges, there are opportunities ciation for Newcomers to Canada. as well. PEIANC appreciates the A special thank you goes out to continued funding support from Federal and Provincial funding all levels of government to sup- partners, as well as municipalities port newcomers to PEI. New ar- and donors, for their continued rivals, from 78 different countries, support of the Association. totalled 1,987 and included 1,310 I was once a newcomer to permanent residents, 640 tem- Canada, arriving in 1971 from a refugee camp in Italy. porary residents, and 37 others. The largest intake was I can relate to the difficulties one can encounter when from China, and we saw increasing numbers from India, entering a new country, a new home, a new way of life, Vietnam, and the Philippines. We also welcomed 132 and the challenges one faces when adapting to a new cul- refugees. I completed my two-year term as Co-Chair of ture. -

Annual Report

Annual Report 2019-2020 What’s in this report Page • The Literacy Crisis 1 • Our Mission 2 • Year at a Glance (2019-2020) 3 • Ready Set Learn 4 • Free Books for Kids 5 • Adult Learner Awards 6 • Essential Skills for Atlantic Fisheries 7 • PGI Golf Tournament for Literacy 8 • Public Awareness 9 • Our Member Organizations 10 • Our Board of Directors 11 • Our Team 12 • Our Core Funder 13 The Literacy Crisis Literacy is a basic human right. 40% of kindergarten-aged children in PEI who completed the Early Years Evaluation did not meet the developmental milestones in at least one of the five skill areas. (2017 Children’s Report) 1200 Island children in grades K to 6 were referred to us by resource teachers this year because they were struggling with reading, writing and/or math. Note: This number is likely higher as we limit the number of referrals teachers can send in. 45% of working-aged Islanders don’t have the literacy skills needed to succeed in our digital world. (PIAAC 2012) We are determined to change these statistics 1 Our Mission We work to advance literacy for the people of Prince Edward Island We exist so that: • gaps and overlaps in literacy services will be decreased • barriers to people with low literacy levels will be reduced • Islanders will be better informed about the personal costs of low literacy on economic, cultural, political and social aspects of life • literacy will be valued and celebrated across PEI 2 Year at a Glance (2019-2020 Fiscal) Funding Secured $645,073 Because the Alliance existed this year: • 1198 children boosted their literacy skills, confidence, and learning attitudes • 1735 books were distributed to families • 11 adults gained literacy and employability skills and 8 were employed after the program • Thousands of Islanders are better informed about literacy in PEI 3 Since 2001 Ready Set Learn “I learned that if I try hard I can do it” grade 2 participant We ran our free summer tutoring program for the 19th year during the summer and school-year. -

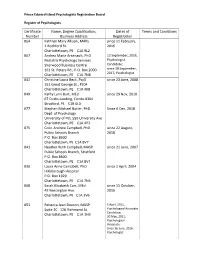

Certificate Number Name, Degree Qualification, Business Address

Prince Edward Island Psychologists Registration Board Register of Psychologists Certificate Name, Degree Qualification, Dates of Terms and Conditions Number Business Address Registration 064 Kathren Mary Allison, MAPs since 11 February, 1 Rochford St. 2016 Charlottetown, PE C1A 9L2 067 Andrea Marie Arsenault, PhD 13 September, 2016, Pediatric Psychology Services Psychologist Sherwood Business Centre Candidate; 161 St. Peters Rd., P.O. Box 2000 since 28 September, Charlottetown, PE C1A 7N8 2017, Psychologist 042 Christine Laura Beck, PsyD since 23 June, 2008 151 Great George St., #204 Charlottetown, PE C1A 4K8 049 Kathy Lynn Burt, MEd since 29 Nov, 2010 67 Ducks Landing, Condo #304 Stratford, PE C1B 0L3 077 Stephen Michael Butler, PhD Since 6 Dec, 2018 Dept. of Psychology University of PEI, 550 University Ave Charlottetown, PE C1A 4P3 075 Colin Andrew Campbell, PhD since 22 August, Public Schools Branch 2018 P.O. Box 8600 Charlottetown, PE C1A 8V7 041 Heather Ruth Campbell, MASP since 21 June, 2007 Public Schools Branch, Stratford P.O. Box 8600 Charlottetown, PE C1A 8V7 036 Laura Anne Campbell, PhD since 1 April, 2004 Hillsborough Hospital P.O. Box 1929 Charlottetown, PE C1A 7N5 068 Sarah Elizabeth Carr, MEd since 11 October, 49 Kensington Ave. 2016 Charlottetown, PE C1A 3V6 051 Rebecca Jean Deacon, MASP 5 April, 2011, Suite 2C 126 Richmond St. Psychological Associate Candidate; Charlottetown, PE C1A 1H9 30 May, 2011, Psychological Associate; since 16 June, 2016, Psychologist Prince Edward Island Psychologists Registration Board Register of Psychologists 025 Nadine Alison DeWolfe, PhD since 20 April, 1999 Sherwood Business Centre Pediatric Psychology Services P.O. -

Town of Stratford 2015 Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventory Ben Grieder

Town of Stratford 2015 Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventory Ben Grieder This document outlines the methodology, calculations results, quality control methods and the primary sources used to create the 2015 Greenhouse Gas Inventory for the Town of Stratford. The PCP Protocol: Canadian Supplement to International Emission Analysis Protocol was used as a guiding document throughout the creation of this Town of Stratford inventory. All required fields of data collection were completed along with some optional fields included in the 234 Shakespeare Avenue, Corporate Inventory. Appendix items included in this Stratford, PEI document will help guide the creation of future inventories 902- 5 6 9 - 1995 that occur in the Town of Stratford. 902- 5 6 9 - 5000 1 2 / 1 5 / 2 0 1 6 Contents List of Tables and Figures .............................................................................................................................. 2 Definitions ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Exceutive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Establishing Operational Boundaries ............................................................................................................ 7 Corporate Inventory ................................................................................................................................. 7 -

Ivities Date

Fall/Winter 2019 ACT UP PrinceIVITIES Edward Island Advisory Council onDATE the Status of Women NEW COUNCIL CHAIRPERSON’S MESSAGE: CHAIRPERSON DEBBIE LANGSTON The PEI Advisory I am honoured to be appointed as Council on the Chairperson of the PEI Advisory Status of Women is Council on the Status of Women, and very pleased that I am looking forward to undertaking the Government the work, pushing forward with our of Prince message, and advocating for gender Edward Island equality for all Islanders. has appointed Debbie Langston of I am happy my appointment Blooming Point to chair the Council comes in time to lead the Purple from October 2019 to the end of her Ribbon Campaign Against Violence term in March 2021. Debbie previously Against Women, as we prepare served as Vice-Chairperson. for a meaningful December 6th Debbie and her sisters were raised Montreal Massacre Memorial Service by their mother in the UK. After to commemorate 30 years since leaving school, Debbie worked for the 14 women lost their lives at l’Ecole Metropolitan Police Service, where Polytechnique, just because they were she met her husband Robin. They women. immigrated to Canada with their young I am likewise looking forward to family in 2004. Debbie graduated from meeting four newly appointed Council the Holland College Child and Youth members who will join us at the table. Care Worker course in 2009 and is currently enrolled in the Bachelor of I would like to thank Council staff, Jane, Arts program at UPEI. She has worked Michelle, and Becky, and all the women in a variety of settings and is currently who served on the Council this past employed as a Youth Service Worker year for a successful year of advising with the Public Schools Branch. -

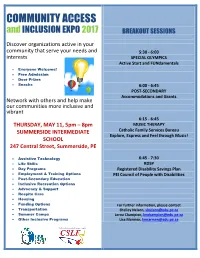

COMMUNITY ACCESS Invitation for Emailing.Pdf

COMMUNITY ACCESS and INCLUSION EXPO 2017 BREAKOUT SESSIONS Discover organizations active in your community that serve your needs and 5:30 - 6:00 interests SPECIAL OLYMPICS Active Start and FUNdamentals Everyone Welcome! Free Admission Door Prizes Snacks 6:00 - 6:45 POST-SECONDARY Accommodations and Grants Network with others and help make our communities more inclusive and vibrant 6:15 - 6:45 THURSDAY, MAY 11, 5pm – 8pm MUSIC THERAPY SUMMERSIDE INTERMEDIATE Catholic Family Services Bureau Explore, Express and Feel through Music! SCHOOL 247 Central Street, Summerside, PE Assistive Technology 6:45 - 7:30 Life Skills RDSP Day Programs Registered Disability Savings Plan Employment & Training Options PEI Council of People with Disabilities Post-Secondary Education Inclusive Recreation Options Advocacy & Support Respite Care Housing Funding Options For further information, please contact Transportation Shelley Nelson, [email protected] Summer Camps Lorna Champion, [email protected] Other Inclusive Programs Lisa Marmen, [email protected] Community Access & Inclusion Expo 2017 – Invited Agencies Thursday, May 11th, 2017 5:00 – 8:00 pm – Summerside Intermediate School The following agencies and services have been invited to participate: Aboriginal Women’s Association of PEI Joyriders Therapeutic Riding Association of PEI Academy of Learning College Just Being Kids (Montague) Access Advisor K & K Quality Care (Charlottetown) Actions Femmes Kids West (Alberton) Adult Education Holland College L’Association des centres de la petite enfance francophone de l’Î.-P.-É. Adventure Group Inc. La Coopérative services jeunesse Andrews of PEI La Coopérative d’intégration francophone de l’Île-du Prince Édouard Angel Hooves Equine Assisted Psychotherapy & Rhythmic Riding La Commission scolaire de langue française Another Way - Learning & Social Center La Fédération des parents de l’Î.-P.-É. -

Stratford's Community Energy Plan to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions

2017 Stratford’s Community Energy Plan to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions Stratford’s Third Milestone of the Partners for Climate Protection Program STRATFORD COMMUNITY ENERGY PLAN Please cite this document as follows: Stratford’s Community Energy Plan to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Stratford Sustainability Committee. Town of Stratford. 2017. Acknowledgements Under the guidance of Town Council, Stratford’s Sustainability Committee along with the CAO’s Office supervised the development of the plan with the active involvement of the Advisory Committee, Steering Committee, various stakeholders and town staff. Work Team Members (Sustainability Committee): 1. David Dunphy: Mayor of the Town of Stratford. 2. Jody Jackson: Chair of the Sustainability Committee and Town Councilor. 3. Keith Maclean: Town Councilor. 4. Robert Hughes: CAO of the Town of Stratford. 5. Ben Grieder: Stratford Community Energy Plan Coordinator. 6. Jill Burridge: Resident of Stratford. 7. Rosemary Curley: Resident of Stratford. 8. Andrew Davies: Resident of Stratford. 9. Joel Ives: Resident of Stratford. 10. Chris Jones: Resident of Stratford. 11. Aaron MacDougall: Resident of Stratford. Financial Support We could not have completed this community energy plan (CEP) without funding from various government, utility and non-profit organizations. Funding organizations went above and beyond the original financial support requested of them. The Town of Stratford would like to acknowledge the support of those organizations: Organization Funding (Canadian Dollars) Federation of Canadian Municipalities-Green $30,000 Municipal Fund Maritime Electric $1,500 with additional In-kind support PEI Energy Corporation $5,000 with additional In-kind support PEI Office of Energy Efficiency $5,000 with additional In-kind support Stratford Area Watershed Improvement Group $3,000 of In-kind support Town of Stratford $10,000 with an additional $5,000 of In-kind support Public & Stakeholder Engagement Over 500 local citizens contributed ideas and feedback to this Plan. -

Prince Edward Island Summary of Education Updates

COVID-19 Prince Edward Island Summary of Education Updates July 31, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND | Summary of the Government’s Response to COVID-19 ..................................................................................................... 3 Preschool & Daycare – Department of Education and Lifelong Learning ................................................................................................................. 3 Early years centres ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Licensed child care centres .................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Kindergarten to High School – Department of Education and Lifelong Learning ...................................................................................................... 4 Private .................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Post-Secondary Institutions – Department of Education and Lifelong Learning ....................................................................................................... 6 University of Prince Edward Island ...................................................................................................................................................................... -

2018 Equality Report Card

Prince Edward Island EQUALITY REPORT CARD 2018 PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND SCORING KEY ADVISORY COUNCIL ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN EQUALITY REPORT CARD The 2018 Equality Report Card rates the Prince 2018 Edward Island government’s progress towards The Equality Report Card is a process women’s equality goals as a B– (70.3/100). to assess Prince Edward Island’s 26.8 out of a possible 45 points progress towards women’s equality for PRIORITY ACTION AREAS set by the PEIACSW goals. The PEI Advisory Council on These priority action areas were selected from the Status of Women’s goal is to work recommendations the Advisory Council has made collaboratively with government to to government in past Report Cards, briefs and help the Province achieve high grades submissions, policy guides, and formal meetings. in all categories. Some recommendations date back many years. The priority actions and other Little or No Progress = 0.3 point Some Progress = 0.65 point considerations assessed in the 2018 Good Progress = 1 point Equality Report Card were established for the mandate of government 33.5 out of a possible 45 points which began in May 2015. They were for OTHER CONSIDERATIONS in nine categories made public in June 2016. This report These considerations include initiatives that assesses actions by government government nominated and Council assessed as updated to December 31, 2017, except good practices to support equality goals. where more recent dates are noted. Much Worse = 1 point Previous Equality Report Cards were Somewhat Worse = 2 points published in 2008 (pilot), 2009, 2011, Status Quo = 3 points 2013, and 2015. -

2020 Annual Report Showcases This Reality

Annual Report 2020 The Board of Directors is pleased to support the 2020 Big Brothers Big Sisters of PEI Annual Report. Observationally, the past year has been one of change, concern, effort, creativity, and importantly, success for the agency. The leadership and positivity displayed by the entire Big Brothers Big Sisters of PEI staff must be recognized while a global pandemic continues to significantly impact how youth are supported across Prince Edward Island. Over the past year, the agency remained open in their communications and enacted several program adjustments and new operational strategies to meet the mandate of the organization. The Board of Directors is confident that information within the 2020 Annual Report showcases this reality. Tim McRoberts Chair, BBBSPEI 1 | P a g e BBBSPEI 2020 Annual Report 2 | P a g e BBBSPEI 2020 Annual Report 2019-2020 BOARD of DIRECTORS CHAIR: Tim McRoberts VICE-CHAIR: Lisa Doyle-MacBain RETURNING DIRECTORS David Green (Past-Chair) Rob Saada Gary Conohan John D. Farrell Jessica Gillis NEW DIRECTORS: Kieran Goodwin Olivia MacDonald Maggie Grimmer Jacob Zelman HONORARY BOARD MEMBER: Dennis Carver Meet Our STAFF Karen Pirch Administrative Assistant Mary Claire Fox Mentoring Coordinator Match Support Kathy Jenkins Mentoring Coordinator Match Support (Oct 2018-March 2019) Pam Murray Mentoring Coordinator Match Support Nikki Roberts Teen Mentoring Coordinator Tracy Lynn Ellsworth Post-Secondary and Career Readiness Coordinator Mary Carr-Chaisson Fund Development Coordinator (to November 2019) Lyndsay Charlton Fund Development Coordinator (November 2019) Heather Doran Communication and Development Manager Myron Yates Executive Director 3 | P a g e BBBSPEI 2020 Annual Report Big Brothers Big Sisters of PEI continues to assist children to reach their potential.