A Note on the Ramayana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ancient Mesopotamian Place Name “Meluḫḫa”

THE ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN PLACE NAME “meluḫḫa” Stephan Hillyer Levitt INTRODUCTION The location of the Ancient Mesopotamian place name “Meluḫḫa” has proved to be difficult to determine. Most modern scholars assume it to be the area we associate with Indus Valley Civilization, now including the so-called Kulli culture of mountainous southern Baluchistan. As far as a possible place at which Meluḫḫa might have begun with an approach from the west, Sutkagen-dor in the Dasht valley is probably as good a place as any to suggest (Possehl 1996: 136–138; for map see 134, fig. 1). Leemans argued that Meluḫḫa was an area beyond Magan, and was to be identified with the Sind and coastal regions of Western India, including probably Gujarat. Magan he identified first with southeast Arabia (Oman), but later with both the Arabian and Persian sides of the Gulf of Oman, thus including the southeast coast of Iran, the area now known as Makran (1960a: 9, 162, 164; 1960b: 29; 1968: 219, 224, 226). Hansman identifies Meluḫḫa, on the basis of references to products of Meluḫḫa being brought down from the mountains, as eastern Baluchistan in what is today Pakistan. There are no mountains in the Indus plain that in its southern extent is Sind. Eastern Baluchistan, on the other hand, is marked throughout its southern and central parts by trellised ridges that run parallel to the western edge of the Indus plain (1973: 559–560; see map [=fig. 1] facing 554). Thapar argues that it is unlikely that a single name would refer to the entire area of a civilization as varied and widespread as Indus Valley Civilization. -

Ch. 3 MALE DEITIES I. Worship of Vishnu and Its Forms in Goa Vishnu

Ch. 3 MALE DEITIES I. Worship of Vishnu and its forms in Goa Vishnu is believed to be the Preserver God in the Hindu pantheon today. In the Vedic text he is known by the names like Urugai, Urukram 'which means wide going and wide striding respectively'^. In the Rgvedic text he is also referred by the names like Varat who is none other than says N. P. Joshi^. In the Rgvedhe occupies a subordinate position and is mentioned only in six hymns'*. In the Rgvedic text he is solar deity associated with days and seasons'. References to the worship of early form of Vishnu in India are found in inscribed on the pillar at Vidisha. During the second to first century BCE a Greek by name Heliodorus had erected a pillar in Vidisha in the honor of Vasudev^. This shows the popularity of Bhagvatism which made a Greek convert himself to the fold In the Purans he is referred to as Shripati or the husband oiLakshmi^, God of Vanmala ^ (wearer of necklace of wild flowers), Pundarikaksh, (lotus eyed)'". A seal showing a Kushan chief standing in a respectful pose before the four armed God holding a wheel, mace a ring like object and a globular object observed by Cunningham appears to be one of the early representations of Vishnu". 1. Vishnu and its attributes Vishnu is identified with three basic weapons which he holds in his hands. The conch, the disc and the mace or the Shankh. Chakr and Gadha. A. Shankh Termed as Panchjany Shankh^^ the conch was as also an essential element of Vishnu's identity. -

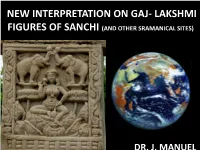

Female Deity of Sanchi on Lotus As Early Images of Bhu Devi J

NEW INTERPRETATION ON GAJ- LAKSHMI FIGURES OF SANCHI (AND OTHER SRAMANICAL SITES) nn DR. J. MANUEL THE BACK GROUND • INDRA RULED THE ROOST IN THE RGVEDIC AGE • OTHER GODS LIKE AGNI, SOMA, VARUN, SURYA BESIDES ASHVINIKUMARS, MARUTS WERE ALSO SPOKEN VERY HIGH IN THE LITERATURE • VISHNU IS ALSO KNOWN WITH INCREASING PROMINENCE SO MUCH SO IN THE LATE MANDALA 1 SUKT 22 A STRETCH OF SIX VERSES MENTION HIS POWER AND EFFECT • EVIDENTLY HIS GLORY WAS BEING FELT MORE AND MORE AS TIME PASSED • Mandal I Sukt 22 Richa 19 • Vishnu ki kripa say …….. Vishnu kay karyon ko dekho. Vay Indra kay upyukt sakha hai EVIDENTLY HIS GLORY WAS BEING FELT MORE AND MORE AS TIME PASSED AND HERO-GODS LIKE BALARAM AND VASUDEVA WERE ACCEPTED AS HIS INCARNATIONS • CHILAS IN PAKISTAN • AGATHOCLEUS COINS • TIKLA NEAR GWALIOR • ARE SOME EVIDENCE OF HERO-GODS BUT NOT VEDIC VISHNU IN SECOND CENTURY BC • There is the Kheri-Gujjar Figure also of the Therio anthropomorphic copper image BUT • FOR A LONG TIME INDRA CONTINUED TO HOLD THE FORT OF DOMINANCE • THIS IS SEEN IN EARLY SACRED LITERATURE AND ART ANTHROPOMORPHIC FIGURES • OF THE COPPER HOARD CULTURES ARE SAID TO BE INDRA FIGURES OF ABOUT 4000 YEARS OLD • THERE ARE MANY TENS OF FIGURES IN SRAMANICAL SITE OF INDRA INCLUDING AT SANCHI (MORE THAN 6) DATABLE TO 1ST CENTURY BCE • BUT NOT A SINGLE ONE OF VISHNU INDRA 5TH CENT. CE, SARNATH PARADOXICALLY • THERE ARE 100S OF REFERENCES OF VISHNU IN THE VEDAS AND EVEN MORE SO IN THE PURANIC PERIOD • WHILE THE REFERENCE OF LAKSHMI IS VERY FEW AND FAR IN BETWEEN • CURIOUSLY THE ART OF THE SUPPOSED LAXMI FIGURES ARE MANY TIMES MORE IN EARLY HISTORIC CONTEXT EVEN IN NON VAISHNAVA CONTEXT AND IN SUCH AREAS AS THE DECCAN AND AS SOUTH AS SRI- LANKA WHICH WAS THEN UNTOUCHED BY VAISHNAVISM NW INDIA TO SRI LANKA AZILISES COIN SHOWING GAJLAKSHMI IMAGERY 70-56 ADVENT OF VAISHNAVISM VISHNU HAD BY THE STARTING OF THE COMMON ERA BEGAN TO BECOME LARGER THAN INDRA BUT FOR THE BUDDHISTS INDRA CONTINUED TO BE DEPICTED IN RELATED STORIES CONTINUED FROM EARLIER TIMES; FROM BUDDHA. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Images of Loss in Tennessee Williams's the Glass Menagerie

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English 11-13-2007 Images of Loss in Tennessee Williams's The Glass Menagerie, Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman, Marsha Norman's night, Mother, and Paula Vogel's How I Learned to Drive Dipa Janardanan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Janardanan, Dipa, "Images of Loss in Tennessee Williams's The Glass Menagerie, Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman, Marsha Norman's night, Mother, and Paula Vogel's How I Learned to Drive." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/23 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Images of Loss in Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie , Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman , Marsha Norman’s ‘night , Mother , and Paula Vogel’s How I Learned to Drive by DIPA JANARDANAN Under the Direction of Matthew C. Roudané ABSTRACT This dissertation offers an analysis of the image of loss in modern American drama at three levels: the loss of physical space, loss of psychological space, and loss of moral space. The playwrights and plays examined are Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie (1945), Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman (1949), Marsha Norman’s ‘night, Mother (1983), and Paula Vogel’s How I Learned to Drive (1998). -

Evolution of Sarasvati in Sanskrit Literature

EVOLUTION OF SARASVATI IN SANSKRIT LITERATURE ABSTRACT SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SANSKRIT BY MOHD. iSRAIL KHAN UNDER THE SUPERVISDN OF Dr. R. S. TRIPATHI PROF. & HEAD OF THE DEPARTMENT OF SANSKRIT ALTGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY A L I G A R H FACULTY OF ARTS ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 1969 ABSTRACT The Hindu mythology is predominontly polytheistic. Gods are numerous and each god or goddess shows very often mutually irreconcilable traits within him or her. This is equally true of Sarasvati, too. She is one of female deities of the Rgvedic times. She has got many peculiarities of her own resulting in complexity of her various conceptions through the ages. In the Rgvedic pantheon, among female deities, Usas, the daughter of the heaven is (divo duhita)/given an exalted place and has been highly extolled as a symbol of poetic beauty. Sarasvati comes next to her in comparison to other Rgvedic goddesses. But in the later period, Usas has lost her superiority and Sarasvati has excelled her. The superiority of Sarasvati is also obvious from another instance. In the Vedic pantheon, many ideitiet s arose and later on merged into others. If any one of them survived,/was mostly in an sterio- typed form. But with Sarasvati, there has been a gradual process of change and development. In her earliest stage, she was a spacious stream having rythmic flow and congenial waters. It was, therefore, but natural that it arrested the attention of seers dwelling along with its banks. They showed their heart-felt reverence to her. -

AGASTYA AGASTYA SARAS AGASTYA KUTA. This Is AGASTYA

AGASTYA AGASTYA SARAS 22) Agastya cursing Dufpanya. Duspanya was the last (6) Agastya gave Sri Rama an arrow, which, when son of the King of Pataliputra. The wicked Duspanya shot at an asura (demon) would pierce his heart, pass had slain a large number of babies, and the King on to the other side, fly to the sea and bathe in the therefore expelled him from the palace. Duspanya sea-water and return to the quiver, it is said. (Uttara went into the forest, where he caught hold of the Ramayana). child of and killed it it Once visited the of Ugraravas by putting under ( 7) Agastya hermitage Apastamba. water. Ugraravas cursed him and accordingly he fell He asked Agastya, who, of Brahma, Visnu and Siva, into water and died and his spirit became a ghost was the Supreme deity. Agastya replied: "These three and wandered about tormented with pain and are only three different manifestations of the one anguish. At last the spirit approached Agastya, who supreme Being". (Brahmapurana). called his disciple Sutisna and asked him to go and (8) For the story of how Agastya cursed the sons of bathe in the Agni tirtha (a bath) in the Gandhama- Manibhadra and transformed them to seven palms, dana mountain and bring some water from the tirtha see the word 'Saptasala'. and sprinkle it on the spirit of Duspanya. Sutisna (9) There was a hermit called Sutisna, to whom Sri acted accordingly and immediately the spirit of Dus- Rama and Laksmana paid a visit when they were panya received divine figure and entered heaven. -

In Praise of Her Supreme Holiness Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi

In praise of Her Supreme Holiness Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi 2016 Edition The original Sahaja Yoga Mantrabook was compiled by Sahaja Yoga Austria and gibven as a Guru Puja gift in 1989 0 'Now the name of your Mother is very powerful. You know that is the most powerful name, than all the other names, the most powerful mantra. But you must know how to take it. With that complete dedication you have to take that name. Not like any other.' Her Supreme Holiness Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi ‘Aum Twameva sakshat, Shri Nirmala Devyai namo namaḥ. That’s the biggest mantra, I tell you. That’s the biggest mantra. Try it’ Birthday Puja, Melbourne, 17-03-85. 1 This book is dedicated to Our Beloved Divine M other Her Supreme Holiness Shri MMMatajiM ataji Nirmal aaa DevDeviiii,,,, the Source of This Knowledge and All Knowledge . May this humble offering be pleasing in Her Sight. May Her Joy always be known and Her P raises always sung on this speck of rock in the Solar System. Feb 2016 No copyright is held on this material which is for the emancipation of humanity. But we respectfully request people not to publish any of the contents in a substantially changed or modified manner which may be misleading. 2 Contents Sanskrit Pronunciation .................................... 8 Mantras in Sahaja Yoga ................................... 10 Correspondence with the Chakras ....................... 14 The Three Levels of Sahasrara .......................... 16 Om ................................................. 17 Mantra Forms ........................................ 19 Mantras for the Chakras .................................. 20 Mantras for Special Purposes ............................. 28 The Affirmations ......................................... 30 Short Prayers for the Chakras ............................. 33 Gāyatrī Mantra ...................................... -

Hindu Students Organization Sanātana Dharma Saṅgha

Hindu Students Organization Sanātana Dharma Saṅgha Table of Contents About HSO 1 Food for Thought 2 Pronunciation Guide 3 Opening Prayers 4 Gaṇesh Bhajans 6 Guru and Bhagavān Bhajans 9 Nārāyaṇa Bhajans 11 Krishṇa Bhajans 13 Rāma Bhajans 23 Devī Bhajans 27 Shiva Bhajans 32 Subramaṇyam Bhajans 37 Sarva Dharma Bhajans 38 Traditional Songs 40 Aartīs 53 Closing Prayers 58 Index 59 About HSO Columbia University’s Hindu Students Organization welcomes you. The Hindu Students Organization (HSO) is a faith-based group founded in 1992 with the intent of raising awareness of Hindu philosophies, customs, and traditions at Columbia University. HSO's major goals are to encourage dialogue about Hinduism and to provide a forum for students to practice the faith. HSO works with closely with other organizations to host joint events in an effort to educate the general public and the Columbia community. To pursue these goals, HSO engages in educational discussions, takes part in community service, and coordinates religious and cultural events including the following: Be the Change Day Navaratri Diwali Saraswati/Ganesh Puja Study Breaks Lecture Events Shruti: A Classical Night Holi Weekly Bhajans and Discussion Circle/Bhajans Workshop Interfaith Events Interviews to become a part of HSO’s planning board take place at the start of the fall semester. If you are interested in joining our mailing list or if you would like to get in touch with us, email us at [email protected] or visit us at http://www.columbia.edu/cu/hso/! 1 Food For Thought Om - “OM - This Imperishable Word is the whole of this visible universe. -

Sita Ram Baba

सीता राम बाबा Sītā Rāma Bābā סִיטָ ה רְ אַמָ ה בָבָ ה Bābā بَابَا He had a crippled leg and was on crutches. He tried to speak to us in broken English. His name was Sita Ram Baba. He sat there with his begging bowl in hand. Unlike most Sadhus, he had very high self- esteem. His eyes lit up when we bought him some ice-cream, he really enjoyed it. He stayed with us most of that evening. I videotaped the whole scene. Churchill, Pola (2007-11-14). Eternal Breath : A Biography of Leonard Orr Founder of Rebirthing Breathwork (Kindle Locations 4961-4964). Trafford. Kindle Edition. … immortal Sita Ram Baba. Churchill, Pola (2007-11-14). Eternal Breath : A Biography of Leonard Orr Founder of Rebirthing Breathwork (Kindle Location 5039). Trafford. Kindle Edition. Breaking the Death Habit: The Science of Everlasting Life by Leonard Orr (page 56) ראמה راما Ράμα ראמה راما Ράμα Rama has its origins in the Sanskrit language. It is used largely in Hebrew and Indian. It is derived literally from the word rama which is of the meaning 'pleasing'. http://www.babynamespedia.com/meaning/Rama/f Rama For other uses, see Rama (disambiguation). “Râm” redirects here. It is not to be confused with Ram (disambiguation). Rama (/ˈrɑːmə/;[1] Sanskrit: राम Rāma) is the seventh avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu,[2] and a king of Ayodhya in Hindu scriptures. Rama is also the protagonist of the Hindu epic Ramayana, which narrates his supremacy. Rama is one of the many popular figures and deities in Hinduism, specifically Vaishnavism and Vaishnava reli- gious scriptures in South and Southeast Asia.[3] Along with Krishna, Rama is considered to be one of the most important avatars of Vishnu. -

Implications for the Modern Hindu Woman in Partial Fulhlment of the Requirements for MASTER of ARTS University of Manitoba Winni

Sitã in Tulasidãsa' s Rãmachari tamãnasa: Implications for the Modern Hindu Woman by Karen E. Green Submiued to the #ii:t Graduate studies in Partial Fulhlment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Religion University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba (c) August, 1993 NationalLibrarY Bibliothèque nationale W@W du Canada et Acouisitions and Direction des acquisitions BibliograPhic Services Branch des services bibliograPhiques Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington 395 (Ontario) Otiawa, Ontario Onawa K1A ON4 K1A ON4 YNt Iile Volre rèlërffie Our lile Nolre èl,ffie The author has E¡'anted an ß-'auteu¡r a accordé !'Jne ßice¡rce et non exclusive i nrevocable non-exclus¡ve licemce irnévoeable tslbliotlrèque allowing the frtüatio¡'lal ü-ibrary of perrnettarxt à la Ca¡rada to reproduce, loan, matio¡'¡ale du Canada de distribute 0r sell cop¡es of reproduire, Prêter, distribuer ou sa thèse his/l,er thesis bY anY sneans and vendre des coPies de sous in any for¡m or format, maldng de quelque manière et que ce soit this thesis available to interested EuelEue for¡ne Pour de cette persons. mettre des exemPlaires thèse à !a disPosition des personnes intéressées. du The author retains owt'lershiP ot t-'auteur conserve la ProPriété the copyrlght in his/her tl'lesis' droit d'auteur qu¡ Protège sa ¡ri des extraits hleither the thesis nor substantia! thèse. F',üi !a thèse ne extracts from it maY be Printed or substantiels de celle-ci otherwise reProduced without doivent être irnPrimés oL¡ son his/her permiss¡on" autrement reProduits sans autorisation.