Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download CV (PDF)

Anuradha Vikram anu(at)curativeprojects(dot)net About Anuradha (Curative Projects) Independent curator and scholar working with museums, galleries, journals, and websites to develop original curatorial work including exhibitions, public programs, and artist-driven publications. Consultant for strategic planning, institutional vision, content strategy, and diversity, equity, and inclusion work. Current engagements include Craft Contemporary, LA Freewaves, MhZ Curationist, LACE, X-TRA, X Artists’ Books, and UCLA Art Sci Center. Education M.A., Curatorial Practice, California College of the Arts, San Francisco, CA, 2005 B.S., Studio Art, minor in Art History, New York University, New York, NY, 1997 Curated Exhibitions, Performances, and Public Art 2024 ▪ Co-curator, Atmosphere of Sound: Sonic Art in Times of Climate Disruption (with Victoria Vesna), UCLA Art Sci Center at Center for Art of Performance, Getty Pacific Standard Time: Art x Science x LA, dates TBC. 2023 ▪ Unmaking/Unmarking: Archival Poetics and Decolonial Monuments, LACE, Los Angeles, dates TBC. 2022 ▪ Jaishri Abichandani: Lotus-Headed Children, Craft Contemporary, Los Angeles, CA, January 30–May 8. ▪ Exa(men)ing Masculinities, with Marcus Kuiland-Nazario and Anne Bray, LA Freewaves, Los Angeles State Historic Park, dates TBC. 2021 ▪ Atmosphere of Sound: Sonic Art in Times of Climate Disruption, Ars Electronica 2021 Garden, September 8-12. ▪ Juror, FRESH 2021, SoLA Contemporary. August 28-October 9. 2020 ▪ Patty Chang: Milk Debt, 18th Street Arts Center, Santa Monica, CA, October 19-January 22, 2021. Traveled to PioneerWorks, Brooklyn, March 19-May 23, 2021. ▪ Co-curator, Drive-By-Art (with Warren Neidich, Renee Petropoulos, and Michael Slenske). Citywide exhibition, Los Angeles, May 23-31. -

The Influence of the Los Angeles ``Oligarchy'' on the Governance Of

The influence of the Los Angeles “oligarchy” onthe governance of the municipal water department (1902-1930): a business like any other or a public service? Fionn Mackillop To cite this version: Fionn Mackillop. The influence of the Los Angeles “oligarchy” on the governance of the municipal wa- ter department (1902-1930): a business like any other or a public service?. Business History Conference Online, 2004, 2, http://www.thebhc.org/publications/BEHonline/2004/beh2004.html. hal-00195980 HAL Id: hal-00195980 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00195980 Submitted on 11 Dec 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Influence of the Los Angeles “Oligarchy” on the Governance of the Municipal Water Department, 1902- 1930: A Business Like Any Other or a Public Service? Fionn MacKillop The municipalization of the water service in Los Angeles (LA) in 1902 was the result of a (mostly implicit) compromise between the city’s political, social, and economic elites. The economic elite (the “oligarchy”) accepted municipalizing the water service, and helped Progressive politicians and citizens put an end to the private LA City Water Co., a corporation whose obsession with financial profitability led to under-investment and the construction of a network relatively modest in scope and efficiency. -

Los Angeles Bibliography

A HISTORICAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT IN THE LOS ANGELES METROPOLITAN AREA Compiled by Richard Longstreth 1998, revised 16 May 2018 This listing focuses on historical studies, with an emphasis is on scholarly work published during the past thirty years. I have also included a section on popular pictorial histories due to the wealth of information they afford. To keep the scope manageable, the geographic area covered is primarily limited to Los Angeles and Orange counties, except in cases where a community, such as Santa Barbara; a building, such as the Mission Inn; or an architect, such as Irving Gill, are of transcendent importance to the region. Thanks go to Kenneth Breisch, Dora Crouch, Thomas Hines, Greg Hise, Gail Ostergren, and Martin Schiesl for adding to the list. Additions, corrections, and updates are welcome. Please send them to me at [email protected]. G E N E R A L H I S T O R I E S A N D U R B A N I S M Abu-Lughod, Janet, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles: America's Global Cities, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999 Adler, Sy, "The Transformation of the Pacific Electric Railway: Bradford Snell, Roger Rabbit, and the Politics of Transportation in Los Angeles," Urban Affairs Quarterly 27 (September 1991): 51-86 Akimoto, Fukuo, “Charles H. Cheney of California,” Planning Perspectives 18 (July 2003): 253-75 Allen, James P., and Eugene Turner, The Ethnic Quilt: Population Diversity in Southern California Northridge: Center for Geographical Studies, California State University, Northridge, 1997 Avila, Eric, “The Folklore of the Freeway: Space, Culture, and Identity in Postwar Los Angeles,” Aztlan 23 (spring 1998): 15-31 _________, Popular Culture in the Age of White Flight: Fear and Fantasy in Suburban Los Angeles, Berkeley: University of California Pres, 2004 Axelrod, Jeremiah B. -

State of Immigrants in LA County

State of Immigrants, 1 Los Angeles County State of Immigrants in LA County January 2020 USC Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration and release of this report. Finally, thank you to CCF, State of Immigrants, 2 (CSII) would like to thank everyone involved in the James Irvine Foundation, Bank of America, and Los Angeles County producing the first annual State of Immigrants in Jonathan Woetzel for their support which made L.A. County (SOILA) report. The goal was to create a SOILA possible. resource for community-based organizations, local governments, and businesses in their immigrant We would also like to extend deep appreciations integration efforts. To that end, we sought the to the members of the CCF Council on Immigrant wisdom of a range of partners that have made this Integration for commissioning this report and for report what it is. their feedback and suggestions along the way. A special thank you to all organizations interviewed The work here—including data, charts, tables, for case studies that donated their time and Acknowledgments writing, and analysis—was prepared by Dalia expertise to further bolster our analysis. Gonzalez, Sabrina Kim, Cynthia Moreno, and Edward-Michael Muña at CSII. Graduate research assistants Thai Le, Sarah Balcha, Carlos Ibarra, and Blanca Ramirez heavily contributed to charts, writing, and analysis. Thank you to Manuel Pastor and Rhonda Ortiz at CSII, as well as Efrain Escobedo and Rosie Arroyo from the California Community Foundation (CCF) for their direction, feedback, and support that fundamentally shaped this report. Sincere appreciations to Justin Scoggins (CSII) for his thoughtful and thorough data checks. -

Understanding Artworlds. INSTITUTION Getty Center for Education in the Arts, Los Angeles, CA

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 445 980 SO 031 915 AUTHOR Erickson, Mary; Clover, Faith TITLE Understanding Artworlds. INSTITUTION Getty Center for Education in the Arts, Los Angeles, CA. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 108p. AVAILABLE FROM Getty Center for Education in the Arts, 1875 Century Park East, Suite 2300, Los Angeles, CA 90067-2561; Web site: http://www.artsednet.getty.edu/ArtsEdNet/Resources. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Art Activities; *Art Education; *Art Expression; *Cultural Context; Inquiry; Interdisciplinary Approach; Secondary Education; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *California (Los Angeles); Conceptual Frameworks; Web Sites ABSTRACT This curriculum unit consists of four lessons that are designed to broaden students' understanding of art and culture; each lesson can stand alone or be used in conjunction with the others. The introduction offers a conceptual framework of the Artworlds unit, which takes an inquiry-based approach. The unit's first lesson, "Worlds within Worlds," is an interdisciplinary art and social science lesson, an introduction to the concept of culture--an understanding of culture is necessary before students can understand artworlds, the key concept of this curriculum resource. The unit's second lesson, "Places in the LA Artworld," the key lesson in this unit, introduces and illustrates the defining characteristics of an artworld. The lesson has students make an artworld bulletin board. The unit's third lesson, "Cruising the LA Artworld," asks students to apply their understanding of the defining characteristics of artworlds from the "Places in the LA Artworld" lesson to their analysis of art-related Web sites on LA Culture Net and beyond. -

Thegetty INSIDE This Issue

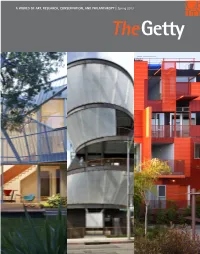

A WORLD OF ART, RESEARCH, CONSERVATION, AND PHILANTHROPY | Spring 2013 TheGetty INSIDE this issue The J. Paul Getty Trust is a cultural Table of CONTENTS and philanthropic institution dedicated to critical thinking in the presentation, conservation, and interpretation of the world’s artistic President’s Message 7 legacy. Through the collective and individual work of its constituent Pacific Standard Time Presents: 8 Programs—Getty Conservation Modern Architecture in L.A. Institute, Getty Foundation, J. Paul Getty Museum, and Getty Research Institute—it pursues its mission in Los Minding the Gap: The Role of Contemporary 11 Angeles and throughout the world, Architecture in the Historic Environment serving both the general interested public and a wide range of In Focus: Ed Ruscha 14 professional communities with the conviction that a greater and more Overdrive: L.A. Constructs the Future 16 profound sensitivity to and knowledge of the visual arts and their many histories is crucial to the promotion Sponsor Spotlight 18 of a vital and civil society. Behind the Scenes: Grantmaking 20 at the Getty New Acquisitions 25 FOR ADVERTISING INFORMATION From The Iris 26 Margaret Malone Cultural Media Inc 1001 W. Van Buren Street New from Getty Publications 28 Chicago, IL, 60607 [email protected] From the Vault 31 (312) 593-3355 On the cover, from left to right: Palms House (detail), Venice, California, 2011, Daly Genik Architects. Photograph Jason Schmidt. © Jason Schmidt; Samitaur Tower (detail), Culver City, California, 2008–10, Eric Owen Moss. Photo: Tom Bonner. © 2011 Tom Bonner; Formosa 1140 (detail), West Hollywood, California, Lorcan O’Herlihy, 2008, © 2009 Lawrence Anderson/Esto © 2013 Published by the J. -

California Native Badge for Cadettes

Native to Greater LA Badge Cadettes GIRL SCOUTS of GREATER LOS ANGELES www.girlscoutsla.org Native to Greater LA Badge (Plants)- Cadettes “When we tug at a single thing in nature, we find it attached to the rest of the world.” ― John Muir Before the 405, the 101, the 5 or the 10, there were plants and animals. Before Hollywood, Los Angeles, Malibu, and Long Beach there were people that lived here for hundreds of years. There are unique plants and animals and people, native only to the region that we call home. Some have vanished in the mists of time, however if we listen to the stories told by the buzz of bees, the crashing of the sea and the voices in the wind, we might just be surprised to still find miracles native only to greater LA. Each level of Cadettes, Seniors and Ambassadors will learn about one of these elements; eventually tying it all together with the knowledge of Greater LA’s unique natural and cultural history. For Cadettes- Southern California is unique in that there are 5 microclimates: beach, valley, mountain, high desert and low desert. These microclimates are distinctively different and yet sometimes within a matter of miles from each other. As you look through these local regions you will notice some of the unique plant treasures that are found only in these areas. At the basis of almost every food web are plants and they are the same primary producers that provide us with oxygen, food, shelter, and medicine. Some of these plants have incredible adaptations for their environment and are sometimes only found in one place because of these special adaptations. -

Gentrification, Gang Injunctions and Graffiti in Echo Park, Los Angeles A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Getting Up: Gentrification, Gang Injunctions and Graffiti in Echo Park, Los Angeles A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Feminist Studies by Kimberly M. Soriano Committee in charge: Professor Mireille Miler-Young, Chair Professor Jennifer Tyburczy Professor Miroslava Chavez-Garcia June 2019 The thesis of Kimberly M. Soriano is approved. ____________________________________________ Miroslava Chavez-Garcia, Committee Member ____________________________________________ Jennifer Tyburczy, Committee Member ____________________________________________ Mireille Miler-Young Committee Chair June 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible if it were not for my supportive parents, Maria y Juan Soriano Martinez who came from the pueblos of Guerrero y Oaxaca. Gracias por todo lo que hacen por mi y nuestra familia. My amazing sisters Melissa, Rosita and Jessica who have taught me patience, responsibility, feminism and resilience. My adorable nephews for teaching me playfulness and joy. My community and ancestors who inspire me to write with a purpose. My good friend Dario, who supported me materially, physically and emotionally. I would like to thank my amazing M.A. committee and advisor Dr. Mireille Miller-Young, Dr. Jennifer Tyburczy, and Dr. Miroslava Chavez-Garcia. My amazing cohort and friends in Feminist Studies, especially Amoni. Most importantly this thesis is in dedication to my city that is under attack by policy makers that do not care about the survival of Brown and Black people, to the taggers, cholxs, weirdos, organizers and traviesos that continue to pushback, make space, and claim the city despite lack of ownership, this is for us. -

Interpretive Master Plan

LOS ANGELES STATE HISTORIC PARK Interpretive Master Plan August 23, 2006 Los Angeles SHP Interpretive Master Plan August 23, 2006 A state park vision statement describes the “desired future experience” for visitors to the park. The Los Angeles State Historic Park (LASHP) vision helps direct future development through illustration of its “once-in-a-century opportunity” to create a verdant place in the heart of the city where visitors from all social, economic and cultural backgrounds can discover and celebrate the rich cultural connections to Los Angeles history. Vision Visitors to Los Angeles State Historic Park will enjoy a rejuvenating respite from the urban landscape in an open space environment. Visitors will experience the environment through interpretive media and landscape features that recall the historical events of the region. Educational programs and activities will appeal to the interests of many visitors – from the local to the global community, will be varied in media and scope, and will emphasize the City of Los Angeles’ cultural, historic, and commercial heritage. ~ Los Angeles State Historic Park General Plan, May 2005 For general information regarding this document, or to request additional copies, please contact: California State Parks Southern Service Center 8885 Rio San Diego Drive, Suite 270 San Diego, CA 92108 Copyright 2006 California State Parks This publication, including all of the text and photographs, is the intellectual property of California State Parks and is protected by copyright. 2 Los Angeles SHP Interpretive -

Edward Ruscha Photographs of Los Angeles Streets, 1974-2010

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8q81dtw No online items Finding Aid for the Edward Ruscha Photographs of Los Angeles Streets, 1974-2010 Beth Ann Guynn Finding Aid for the Edward 2012.M.2 1 Ruscha Photographs of Los Angeles Streets, 1974-2010 Descriptive Summary Title: Edward Ruscha photographs of Los Angeles streets Date (inclusive): 1974-2010 Number: 2012.M.2 Creator/Collector: Ruscha, Edward Physical Description: 35 Linear Feet Physical Description: 28 boxes Physical Description: 58 GB(3,827 files) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The archive is comprised of Edward Ruscha's ongoing photographic documentation of Los Angeles thoroughfares. Included are shoots of three streets made in the 1970s: Santa Monica Boulevard and Pacific Coast Highway, 1974; and Melrose Avenue, 1975; and over 40 shoots made since 2007. These shoots represent more than twenty-five streets including Sepulveda, Pico, Olympic, Wilshire, La Cienega, and Beverly boulevards. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English. Biographical/Historical Note The American artist Edward Joseph Ruscha IV was born in Omaha, Nebraska on December 16, 1937 to Edward Ruscha III, an insurance auditor, and his wife Dorothy Driscoll Ruscha. He was raised in Oklahoma City where he met his lifelong friends Mason Williams, Joe Goode, and Jerry McMillan. After graduation from high school he drove to California with Mason Williams to attend Chouinard Art Institute (now California Institute of the Arts). -

Los Angeles: Metropolis Despite Nature

Wesleyan University The Honors College Los Angeles: Metropolis despite Nature by Peter Lubershane Class of 2010 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in History Middletown, Connecticut April, 2010 ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………….. iii Preface: Choosing Los Angeles…….…………………... 1 Chapter 1: Quenching a City’s Thirst……………......... 9 Chapter 2: Getting There……………………………... 29 Chapter 3: Seeing America First……………………... 52 Chapter 4: Selling Los Angeles….……………………. 73 Conclusion: Impoverishing the Future…………..…... 95 Bibliography………………………………………….. 104 iii Acknowledgements There are a number of people that I would like to thank for their help and support in the creation of my thesis. From the commencement to the culmination, my advisor, Professor Patricia Hill of Wesleyan University, has been enormously helpful in developing my topics, discussing my researching, and aiding me in the editing process. In addition to Professor Hill, several other people have assisted me: Professor Claire Potter of Wesleyan University provided me with excellent advice while I was developing my topic, Professor Sarah S. Elkind of San Diego State University helped me advance my topic to its final state, and lastly Jennifer Martinez Wormser of the Sherman Library pointed me in the direction of several fascinating archives and led me to some influential sources. The Davenport Committee, who awarded me the Davenport Grant on behalf of the Surdna Foundation in honor of Frederick Morgan Davenport, Wesleyan University Class of 1889, and Edith Jefferson Andrus Davenport, Wesleyan University, Class of 1897, was massively helpful in providing me with the necessary funds to begin my research during the summer before my senior year. -

Empathy As Perception in Downtown Los Angeles and the Walt Disney Concert Hall As an Act of Architecture

Empathy as perception in downtown Los Angeles and the Walt Disney Concert Hall as an act of architecture Daniel G. Geldenhuys Department of Art History, Visual Arts and Musicology, University of South Africa E-mail: [email protected] The present article suggests that empathy is not the sole preserve of human beings, and that a city or buildings can also relate with empathy to people and the environment. The Walt Disney Concert Hall, designed by the architect Frank O. Gehry in downtown Los Angeles, is taken as primary embodiment of such empathy. The article is divided into three sections, framed by a brief introduction and conclu- sion. The first section deals with the historical context of Los Angeles, with special focus on the down- town area, and the way in which the multicultural population has given the city a heterogeneous cul- ture, reflected in its architecture. In the middle section, dealing with how the city relates with empathy to its inhabitants, parallels are drawn with Pretoria and its downtown quarter, providing suggestions for introducing new life, meaning and activities to the Pretoria inner city as a strategy for counteract- ing xenophobia, and improving relationships and engendering respect among divergent cultures. The third section explores the Walt Disney Concert Hall as an act of architecture and work of art, where the macro and micro design have lead to an intelligent strategy of hybridization and inclusiveness. Gehry has in his ingenious design of the theatre complex managed to draw many differences together, allow- ing various cultures and art forms to meet, thus giving empathy a new meaning.