Jewish History of Los Angeles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

72Nd Annual Honoree Celebration 21 Shevat 5779 / January 26, 2019

B’’H 72nd Annual Honoree Celebration 21 Shevat 5779 / January 26, 2019 Pillars of Community: Debbie and David Felsen CSS Volunteers Special Recognition in Appreciation for 50 years of Service: Pearl Bassan Teen Honorees: Renee Fuller Lili Panitch Benji Wilbur Program Shabbat Morning Recognition of Teen Honorees Renee Fuller Lili Panitch Benji Wilbur Saturday Evening Opening Remarks Presentation of Honorees Pillars of the Community Debbie and David Felsen Community Security Service (CSS) Volunteers Recognition of 50 Years of Service Pearl Bassan Closing Remarks Pillars of Special Recognition Community Honorees for 50 Years of Service Debbie and David Felsen Pearl Bassan The Felsens became involved in the Beth Sholom community almost Pearl has been an essential part of Beth Sholom for more than 50 years. immediately upon coming to Potomac. Debbie is the quintessential She has worked with 6 rabbis, 4 executive directors, 2 cantors and in Jewish hostess, opening her home to friends and visitors. Debbie also 2 buildings. An essential component of the transition from 13th and provides support for various programs throughout the shul. David Eastern to Potomac, she takes pride in how she actually became friends served on the Board of Directors and served three terms as President. with many of our members and still keeps in touch with them. Pearl During David’s tenure, Beth Sholom made significant changes, started her Jewish communal career with her husband, Jake, when including the hiring of Rabbanit Fruchter and Executive Director they directed the Hillel at Queens University in Kingston, Ontario. Jessica Pelt, and the initiation of CSS. The Felsens are involved in She brought that same dedication to the entire Washington Jewish learning, fundraising and hospitality throughout the shul and the greater community. -

FIGUEROA 865 South Figueroa, Los Angeles, California

FIGUEROA 865 South Figueroa, Los Angeles, California E T PAU The Westin INGRAHAM ST S Bonaventure Hotel W W 7TH S 4T H ST T S FREMONT AV FINANCIAL Jonathan Club DISTRICT ST W 5TH ST IGUEROA S FLOWER ST Los Angeles ISCO ST L ST S F E OR FWY Central Library RB HA FRANC The California Club S BIX WILSHIR W 8TH ST W 6 E B TH ST LVD Pershing Square Fig at 7th 7th St/ Metro Center Pershing E T Square S AV O D COC ST N S TheThe BLOCBLO R FWY I RA C N ANCA S G HARBO R W 9TH ST F Figueroa HIS IVE ST Los Angeles, CA L O DOW S W 8T 8T H STS T W 6 TH S T S HILL ST W S OLY A MPIC B OOA ST R LVD FIGUE W 9 S ER ST TH ST W O W 7 L Y 7 A TTHH ST S F W S D T LEGENDAADWAY O FIDM/Fashion R Nokia Theatre L.A. LIVE BROB S Metro Station T W Institute of Design S OLYMPI G ST Light Rail StationIN & Merchandising R PPR C BLVD Green SpacesS S T Sites of Interest SST STAPLES Center IN SOUTH PARK ST MA E Parking S IV L S O LA Convention Center E W 1 L ST 1 ND AV Property Description Figueroa is a 35-storey, 692,389 sq ft granite and reflective glass office tower completed in 1991 that is located at the southwest corner of Figueroa Street and 8th Place in Downtown Los Angeles, California. -

Burial Information for These Recipients Is Here

Civil War Name Connection Death Burial Allen, James Enlisted 31Aug1913 Oakland Cemetery Pottsdam, NY St Paul, MNH Anderson, Bruce Enlisted 22Aug1922 Green Hill Cemetery Albany, NY Amsterdam, NY Anderson, Charles W Served 25Feb1916 Thornrose Cemetery (Phorr, George) 1st NY Cav Staunton, VA Archer, Lester Born 27Oct1864 KIA - Fair Oaks, VA Fort Ann, NY IMO at Pineview Cemetery Queensbury, NY Arnold, Abraham Kerns Died 23Nov1901 St Philiips in the Highlands Church Cold Springs, NY Garrison, NY Avery, James Born 11Oct1898 US Naval Hospital New York City, NY Norfolk, VA Avery, William Bailey Served 29Jul1894 North Burial Grounds 1st NY Marine Arty Bayside, RI Baker, Henry Charles Enlisted 3Aug1891 Mount Moriah Cemetery New York City, NY Philadelphia, PA Barnum, Henry Alanson Born 29Jan1892 Oakwood Cemetery Jamesville, NY Syracuse, NY Barrell, Charles Luther Born 17Apr1913 Hooker Cemetery Conquest, NY Wayland, MI Barry, Augustus Enlisted 3Aug1871 Cold Harbor National Cemetery New York City, NY Mechanicsville, VA Barter, Gurdon H Born 22Apr1900 City Cemetery Williamsburg, NY Moscow or Viola, ID** Barton, Thomas C Enlisted Unknown - Lost to History New York City, NY Bass, David L Enlisted 15Oct1886 Wilcox Cemetery New York City, NY Little Falls, NY Bates, Delavan Born 19Dec1918 City Cemetery Seward, NY Aurora, NE Bazaar, Phillip Died 28Dec1923 Calvary Cemetery (Bazin, Felipe) New York City, NY Brooklyn, NY Beddows, Richard Enlisted 15Feb1922 Holy Sepulchre Cemetery Flushing, NY New Rochelle, NY Beebe, William Sully Born 12Oct1898 US Military -

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No. CF No. Adopted Community Plan Area CD Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 08/06/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 3 Woodland Hills - West Hills 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue & 7157 08/06/1962 Sunland - Tujunga - Lake View 7 Valmont Street Terrace - Shadow Hills - East La Tuna Canyon 3 Plaza Church 535 North Main Street and 100-110 08/06/1962 Central City 14 La Iglesia de Nuestra Cesar Chavez Avenue Señora la Reina de Los Angeles (The Church of Our Lady the Queen of Angels) 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill Street 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Dismantled May 1969; Moved to Hill Street between 3rd Street and 4th Street, February 1996 5 The Salt Box 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue (Now 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Moved from 339 Hope Street) South Bunker Hill Avenue (now Hope Street) to Heritage Square; destroyed by fire 1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 South Broadway and 216- 09/21/1962 Central City 14 224 West 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho 10940 North Sepulveda Boulevard 09/21/1962 Mission Hills - Panorama City - 7 Romulo) North Hills 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 09/21/1962 Silver Lake - Echo Park - 1 Elysian Valley 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/02/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 12 Woodland Hills - West Hills 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive, North 11/16/1962 Northeast Los Angeles 14 Figueroa (Terminus), 72-77 Patrician Way, and 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 The Rochester (West Temple 1012 West Temple Street 01/04/1963 Westlake 1 Demolished February Apartments) 14, 1979 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 01/04/1963 Hollywood 13 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 01/28/1963 West Adams - Baldwin Hills - 10 Leimert City of Los Angeles May 5, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Department of City Planning No. -

Anthony C. Beilenson Papers, 1963-1997 LSC.0391

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8580294x No online items Finding Aid for the Anthony C. Beilenson Papers, 1963-1997 LSC.0391 Finding aid prepared by Processed by Chuck Wilson and Dan Luckenbill; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Online finding aid last updated 29 August 2017. Finding Aid for the Anthony C. LSC.0391 1 Beilenson Papers, 1963-1997 LSC.0391 Title: Anthony C. Beilenson Papers Identifier/Call Number: LSC.0391 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 123.0 linear feet296 boxes. 39 cartons. 4 oversize boxes. Date (inclusive): 1963-1997 Abstract: Anthony Charles Beilenson was born on Oct. 26, 1932 in New Rochelle, NY; BA, Harvard Univ., 1954; LL.B, Harvard Univ. Law School, 1957; admitted to CA bar in 1957, and began practice in Beverly Hills; worked as counsel, CA State Assembly Committee on Finance and Insurance, 1960; served in CA State Assembly, 1963-66; served in CA State Senate, 1967-76, where he chaired the Senate Committee on Health and Welfare (1968-74) and the Senate Finance Committee (1975-76); authored more than 200 state laws, including the Therapeutic Abortion Act of 1967, the Auto Repair Fraud Act of 1971, and the Funeral Reform Act of 1971; served as a Democrat in the US House of Representatives, 1977-97; became chair of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (1989-90), and served on the House Budget Committee (1988-94), and the House Rules Committee; did not stand as a candidate for re-election in 1996. -

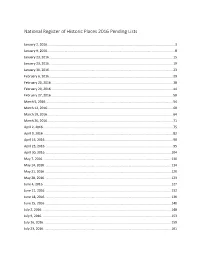

National Register of Historic Places Pending Lists for 2016

National Register of Historic Places 2016 Pending Lists January 2, 2016. ............................................................................................................................................ 3 January 9, 2016. ............................................................................................................................................ 8 January 23, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 15 January 23, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 19 January 30, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 23 February 6, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 29 February 20, 2016. ...................................................................................................................................... 38 February 20, 2016. ...................................................................................................................................... 44 February 27, 2016. ...................................................................................................................................... 50 March 5, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................... -

Surveyla Boyle Heights Pilot Survey Report

SurveyLA Boyle Heights Pilot Survey Report Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning’s Office of Historic Resources Prepared by: Architectural Resources Group, Inc Pasadena, CA April 2010 SURVEYLA BOYLE HEIGHTS PILOT SURVEY REPORT APRIL 2010 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Project Team ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Description of Survey Area ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................................... 5 II. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................ 5 2.1 Summary of Contexts and Themes .......................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Individual Resources ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2.3 Historic Districts .................................................................................................................................................... -

Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, Ph.D. and the Rise of Social Jewish Progressivism in Portland, Or, 1900-1906

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1-1-2010 A Rabbi in the Progressive Era: Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, Ph.D. and the Rise of Social Jewish Progressivism in Portland, Or, 1900-1906 Mordechai Ben Massart Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Massart, Mordechai Ben, "A Rabbi in the Progressive Era: Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, Ph.D. and the Rise of Social Jewish Progressivism in Portland, Or, 1900-1906" (2010). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 729. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.729 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A Rabbi in the Progressive Era: Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, Ph.D. and the Rise of Social Jewish Progressivism in Portland, Or, 1900-1906 by Mordechai Ben Massart A thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: David A. Horowitz Ken Ruoff Friedrich Schuler Michael Weingrad Portland State University 2010 ABSTRACT Rabbi Stephen S. Wise presents an excellent subject for the study of Jewish social progressivism in Portland in the early years of the twentieth-century. While Wise demonstrated a commitment to social justice before, during, and after his Portland years, it is during his ministry at congregation Beth Israel that he developed a full-fledged social program that was unique and remarkable by reaching out not only within his congregation but more importantly, by engaging the Christian community of Portland in interfaith activities. -

8 Unit Multi-Family Investment Opportunity

8 Unit Multi-Family InvestmentOpportunity 14629 Gilmore Street Van Nuys, California 91411 OFFERING MEMORANDUM 14629 GILMORE STREET TABLE OF CONTENTS ➢Property Overview ➢Financial Analysis ➢Comparables ➢Location Overview 14629 Gilmore Street Page 2 SECTION ONE PROPERTY OVERVIEW 14629 Gilmore Street Page 3 PROPERTY OVERVIEW DETAILS Street Address 14629 Gilmore St. Number of Units 8 City Van Nuys Number of Buildings 1 State CA Number of Stories 2 Zip Code 91411 Water Master-Metered APN 2236-017-017 Electric Individually Metered Building Size 6,534 SF Gas Individually Metered Lot Size 7,502 SF Construction Wood-frame Stucco Year Built 1962 Roof Flat Parking 8 Zoning LARD 1.5 Unit Mix (4) 1 Bed / 1 Bath (4) 2 Bed / 1 Bath 14629 Gilmore Street Page 4 PROPERTY OVERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS INVESTMENT DESCRIPTION ➢ Located in the heart of Van Nuys, CA, in the central San Fernando Valley, 14629 Gilmore Street is a prime multifamily value-add investment opportunity. Situated two blocks away from Van Nuys and Victory Boulevards, the 8-unit gated property is within walking distance of Van Nuys High School, Van Nuys City Hall, and many useful and essential services and businesses. EXCELLENT UNIT MIX ➢ 50% 1-bedroom Units, 50% 2-bedroom Units RENTAL UPSIDE ➢ While currently leased to long-term tenants the property boasts significant potential future upside in rents. BUILDING AMENITIES ➢ Gated property, covered parking, on-site laundry 14629 Gilmore Street Page 5 SECTION TWO FINANCIAL ANALYSIS 14629 Gilmore Street Page 6 FINANCIAL ANALYSIS PRICING ANALYSIS $1,800,000 -

Sherman Oaks - Studio City - Toluca Lake - Cahuenga Pass Historic Districts, Planning Districts and Multi-Property Resources – 02/26/13

Sherman Oaks - Studio City - Toluca Lake - Cahuenga Pass Historic Districts, Planning Districts and Multi-Property Resources – 02/26/13 Districts Name: Agnes Avenue Residential Historic District Description: The Agnes Avenue Residential Historic District consists of a grouping of five American Colonial Revival single-family residences lining both sides of Agnes Avenue, between Woodbridge Street on the north and Valleyheart Drive on the south, in Studio City. All of the properties are contributors to the historic district. Ranging from one to one-and-a-half stories, the residences were constructed in 1937 and 1938 as varied but cohesive examples of the American Colonial Revival style. The cohesiveness of the district is further enhanced by its deep, uniform setbacks and large lots, concrete sidewalks and landscaped parkways, mature landscaping and street trees, and period light standards. In addition, a decorative wrought-iron fence spans several of the properties on the west side of Agnes Avenue. Significance: The Agnes Avenue Residential Historic District is significant as an excellent example of American Colonial Revival residential architecture, and as an early residential district associated with the entertainment industry in Studio City. The district’s period of significance is 1937 to 1938, when all of the residences were constructed. The area that comprises the Agnes Avenue Residential Historic District was first subdivided in 1927 by the Central Motion Picture District, Inc., a consortium founded by producer and early Studio City booster and developer Mack Sennett, producer Al Christie, and a group of real estate professionals. The consortium’s goal was to build a new studio in the area, as well as a residential and commercial district "to support the economic growth of their new city." In 1928, Sennett succeeded in establishing Mack Sennett’s Studioland, just across the Los Angeles River from the Agnes Avenue district, which helped jump- start residential settlement in the area. -

The Congregation's Torah

CONGREGATION ADATH JESHURUN aj newsNovember/December 2019 • Heshvan/Kislev/Tevet 5780 Vol. 104 • No. 2 Building with a Purpose by Rav Shai Cherry IT’S THAT TIME AGAIN! In the Tower of Babel story, the crime of their Israel experiences also includes a high school semester generation is unclear. Many commentators with Alexander Muss or Tichon Ramah Yerushalayim. We need to update our records! assume it was their hubris in wanting to build Please see the form on page 7, fill it such a tall tower in order to storm the heavenly My adult education class is off to a strong start. It’s such a out, and mail it to AJ. Alternatively, gates. That seems plausible, but something else delight to see folks so curious about how we got to where you can use the digital form in bothers me. The people set about making bricks we are. The Adult Education committee is also working on the weekly email and email it to before they had decided what to do with them. bringing in outside teachers for both ongoing classes and [email protected]. That’s backwards. It’s like searching for nails single lectures. But we don’t want to overlook the wealth since the only tool you have is a hammer. of talent that we have within our own ranks. If you are an expert on something you find absolutely fascinating — We’ve done it the right way. We’ve spent a year working and you think there’s a chance someone else will, too — on the AJ New Way Forward. -

The Mitzvah of Bikur Cholim Visiting the Sick Part 1

Volume 10 Issue 9 TOPIC The Mitzvah of Bikur Cholim Visiting the Sick Part 1 SPONSORED BY: KOF-K KOSHER SUPERVISION Compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits Reviewed by Rabbi Benzion Schiffenbauer Shlita HALACHICALLY SPEAKING All Piskei Harav Yisroel Belsky Shlita are Halachically Speaking is a reviewed by Harav Yisroel Belsky Shlita monthly publication compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits, a former chaver kollel of Yeshiva SPONSORED: Torah Vodaath and a musmach of Harav Yisroel Belsky Shlita. Rabbi Lebovits currently works as the Rabbinical Administrator for the KOF-K Kosher Supervision. SPONSORED: Each issue reviews a different area of contemporary halacha with an emphasis on practical applications of the principles discussed. Significant time is spent ensuring the inclusion of all relevant shittos on each topic, as well as the psak of Harav Yisroel Belsky, Shlita on current issues. Halachically Speaking wishes all of its readers and WHERE TO SEE HALACHICALLY Klal Yisroel a SPEAKING Halachically Speaking is distributed to many shuls. It can be seen in Flatbush, Lakewood, Five Towns, Far Rockaway, and Queens, The Design by: Flatbush Jewish Journal, baltimorejewishlife.com, The Jewish Home, chazaq.org, and SRULY PERL 845.694.7186 frumtoronto.com. It is sent via email to subscribers across the world. SUBSCRIBE To sponsor an issue please call FOR FREE 718-744-4360 and view archives @ © Copyright 2014 www.thehalacha.com by Halachically Speaking The Mitzvah of Bikur Cholim – Visiting the Sick Part 1 any times one hears that a person he knows is not well r”l and he wishes to go Mvisit him in the hospital or at home.