Empathy As Perception in Downtown Los Angeles and the Walt Disney Concert Hall As an Act of Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Very Special Arts Festival 1980 Bytmc 105

Interim Designation of Agent to Receive Notification of Claimed Infringement Full Legal Name of Service Provider: -------- -------- The Performing Arts Center of Los Angeles County Alternative Name(s) of Service Provider (including all names unde1· which the service provider is doing business): __S_ ee_ A_tt_ac_h_ed_ ________ ______ Address of Service Provider: 135 N. Grand Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90012 Name of Agent Designated to Receive Notification of Claimed Infringement:_L_i_sa_W_ h_itne__y______ _____ _ Full Address of Designated Agent to which Notification Should be Sent (a P.O. Box or similar designation is not acceptable except where it is the only address that can be used in the geographic location): The Music Center, 135 N. Grand Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90012 Telephone Number of Designated Agent:_(_21_3_)_9_72_-_75_1_2______ ___ _ Facsimile Number of Designated Agent:_(_2_13_)_9_7_2-_7_248__ __________ Email Address of Designated Agent: [email protected] ative of the Designating Service Provider: Date: February 24, 2016 Typed or Printed Name and Title: Lisa Whitney, SVP Finance & CFO Note: This Interim Designation Must be Accompanied by a Filing Fee* Made Payable to the Register of Copyrights. *Note: Current and adjusted fees are available on the Copyright website at www.copyright.gov/docs/fees.html Mail the form to: U.S. Copyright Office, Designated Agents P.O. Box 71537 Washington, DC 20024-1537 SCANNED Received APR 18 2017 MAR 1 0 2016 ·copyright Office 2014 135832 11111~ ~rn 11111 111~ ~1111111 m111111111111 mH111rn FILED EXPIRES Mey 19 2014 May 19 2019 Additional Fictitious Names Fictitious Business Na me In Use Sine& 1. -

Download CV (PDF)

Anuradha Vikram anu(at)curativeprojects(dot)net About Anuradha (Curative Projects) Independent curator and scholar working with museums, galleries, journals, and websites to develop original curatorial work including exhibitions, public programs, and artist-driven publications. Consultant for strategic planning, institutional vision, content strategy, and diversity, equity, and inclusion work. Current engagements include Craft Contemporary, LA Freewaves, MhZ Curationist, LACE, X-TRA, X Artists’ Books, and UCLA Art Sci Center. Education M.A., Curatorial Practice, California College of the Arts, San Francisco, CA, 2005 B.S., Studio Art, minor in Art History, New York University, New York, NY, 1997 Curated Exhibitions, Performances, and Public Art 2024 ▪ Co-curator, Atmosphere of Sound: Sonic Art in Times of Climate Disruption (with Victoria Vesna), UCLA Art Sci Center at Center for Art of Performance, Getty Pacific Standard Time: Art x Science x LA, dates TBC. 2023 ▪ Unmaking/Unmarking: Archival Poetics and Decolonial Monuments, LACE, Los Angeles, dates TBC. 2022 ▪ Jaishri Abichandani: Lotus-Headed Children, Craft Contemporary, Los Angeles, CA, January 30–May 8. ▪ Exa(men)ing Masculinities, with Marcus Kuiland-Nazario and Anne Bray, LA Freewaves, Los Angeles State Historic Park, dates TBC. 2021 ▪ Atmosphere of Sound: Sonic Art in Times of Climate Disruption, Ars Electronica 2021 Garden, September 8-12. ▪ Juror, FRESH 2021, SoLA Contemporary. August 28-October 9. 2020 ▪ Patty Chang: Milk Debt, 18th Street Arts Center, Santa Monica, CA, October 19-January 22, 2021. Traveled to PioneerWorks, Brooklyn, March 19-May 23, 2021. ▪ Co-curator, Drive-By-Art (with Warren Neidich, Renee Petropoulos, and Michael Slenske). Citywide exhibition, Los Angeles, May 23-31. -

President's Message

July/Aug 2021 Vol 56-4 63 Years of Dedicated Service to L.A. Your Pension and Health Care Watchdog County Retirees www.relac.org • e-mail: [email protected] • (800) 537-3522 RELAC Joins National Group to Lobby President’s Against Unfair Social Security Reductions Message RELAC has joined the national Alliance for Public Retirees by Brian Berger to support passage of H.R. 2337, proposed legislation to reform the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) of the Social The recovery appears to be on a real path Security Act. to becoming a chapter of our history with whatever sadness or tragedy of which The Alliance for Public Retirees was created nearly a decade we might each have witnessed or been ago by the Retired State, County and Municipal Employees a part. The next few months will be critical as we continue to Association of Massachusetts (Mass Retirees) and the Texas see a further lessening or elimination of restrictions. I don't Retired Teachers Association to resolve the issues of WEP know how I'll ever be able to leave the house or see friends and the Government Pension Offset (GPO). without a mask, at least in the car or in my pocket. In all this Together with retiree organizations, public employee unions past period, however, work has not lessened at RELAC and the and civic associations across the country, the organization programs have continued with positive gains. For that I thank has worked to advance federal legislation through Congress the support staff, each Board member, and the many of you aimed at reforming both the WEP and GPO laws. -

The Influence of the Los Angeles ``Oligarchy'' on the Governance Of

The influence of the Los Angeles “oligarchy” onthe governance of the municipal water department (1902-1930): a business like any other or a public service? Fionn Mackillop To cite this version: Fionn Mackillop. The influence of the Los Angeles “oligarchy” on the governance of the municipal wa- ter department (1902-1930): a business like any other or a public service?. Business History Conference Online, 2004, 2, http://www.thebhc.org/publications/BEHonline/2004/beh2004.html. hal-00195980 HAL Id: hal-00195980 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00195980 Submitted on 11 Dec 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Influence of the Los Angeles “Oligarchy” on the Governance of the Municipal Water Department, 1902- 1930: A Business Like Any Other or a Public Service? Fionn MacKillop The municipalization of the water service in Los Angeles (LA) in 1902 was the result of a (mostly implicit) compromise between the city’s political, social, and economic elites. The economic elite (the “oligarchy”) accepted municipalizing the water service, and helped Progressive politicians and citizens put an end to the private LA City Water Co., a corporation whose obsession with financial profitability led to under-investment and the construction of a network relatively modest in scope and efficiency. -

Schedule and Cost Estimate for an Innovative Boston Harbor Concert Hall

Schedule and Cost Estimate for an Innovative Boston Harbor Concert Hall by Amelie Coste B.S., Civil and Environmental Engineering Ecole Speciale des Travaux Publics, 2003 Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2004 © 2004 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved Signature of A uthor..................... ........................ Deplrtment of Civil And Environmental Engineering n May 7, 2004 Certified by........................... Jerome J Connor Professor of Civil and Envir nmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Certified by..................... ......................... ACA ' 1 Nathaniel Osgood IA Sepior4urer of il and Environmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by .............. ............................ Heidi Nepf Chairman, Committee for Graduate Students MASSACHUSETTS INS OF TECHNOLOGY JUN 0 7 200 4] BARKER LIBRARIE S Schedule and Cost Estimate for an Innovative Boston Harbor Concert Hall By Amelie Coste Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 7, 2004 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering ABSTRACT This thesis formulates a cost estimate and schedule for constructing the Boston Concert Hall, an innovative hypothetical building composed of two concert halls and a restaurant. Concert Halls are complex and expensive structures due to steep design requirements reflecting their status as signature buildings and because they require extensive furnishing. Restaurants are not as complex but require the same kind of attention in their interior furnishing as well as in the choice of their kitchen equipment. Because the structure houses two complicated entities, feasibility analysis required a careful cost and schedule estimation. -

Venues & Spaces the Music Center

WALT DISNEY CONCERT HALL The Music Center Venues & Spaces Completed in 2003, Walt Disney Concert Hall is an 135 N. Grand Avenue The Music Center provides a state-of-the-art architectural masterpiece designed by Frank Gehry. Los Angeles, CA 90012 experience—from the design of its buildings, The Concert Hall is home to the LA Phil and the musiccenter.org Los Angeles Master Chorale and is one of the most to the programming and amenities it offers (213) 972-7211 acoustically sophisticated venues in the world, providing to more than two million people each year both visual and aural intimacy for a singular musical across its 12-acre campus. experience. THE MUSIC CENTER PLAZA DOROTHY CHANDLER PAVILION The Music Center Plaza is a beautiful 35,000 square- Opened in 1964, the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, the first TE MP foot outdoor urban oasis and destination for arts and L E ST and largest of The Music Center’s theatres, has been the REET community programming such as The Music Center’s site of unparalleled performances by stunning music and highly popular Dance DTLA, along with festivals, dance luminaries and virtuosos. With one of the largest concerts and other special events. The “plaza for all” Cocina Roja stages in the U.S., the Pavilion was the site for more than welcomes all and brings to life the strength and diversity 20 Academy Awards presentations from 1969–1999. It is of Los Angeles County with a range of dining options, now the home of LA Opera and Glorya Kaufman Presents refreshing gardens, an iconic fountain and views of Dance at The Music Center. -

Los Angeles Bibliography

A HISTORICAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT IN THE LOS ANGELES METROPOLITAN AREA Compiled by Richard Longstreth 1998, revised 16 May 2018 This listing focuses on historical studies, with an emphasis is on scholarly work published during the past thirty years. I have also included a section on popular pictorial histories due to the wealth of information they afford. To keep the scope manageable, the geographic area covered is primarily limited to Los Angeles and Orange counties, except in cases where a community, such as Santa Barbara; a building, such as the Mission Inn; or an architect, such as Irving Gill, are of transcendent importance to the region. Thanks go to Kenneth Breisch, Dora Crouch, Thomas Hines, Greg Hise, Gail Ostergren, and Martin Schiesl for adding to the list. Additions, corrections, and updates are welcome. Please send them to me at [email protected]. G E N E R A L H I S T O R I E S A N D U R B A N I S M Abu-Lughod, Janet, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles: America's Global Cities, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999 Adler, Sy, "The Transformation of the Pacific Electric Railway: Bradford Snell, Roger Rabbit, and the Politics of Transportation in Los Angeles," Urban Affairs Quarterly 27 (September 1991): 51-86 Akimoto, Fukuo, “Charles H. Cheney of California,” Planning Perspectives 18 (July 2003): 253-75 Allen, James P., and Eugene Turner, The Ethnic Quilt: Population Diversity in Southern California Northridge: Center for Geographical Studies, California State University, Northridge, 1997 Avila, Eric, “The Folklore of the Freeway: Space, Culture, and Identity in Postwar Los Angeles,” Aztlan 23 (spring 1998): 15-31 _________, Popular Culture in the Age of White Flight: Fear and Fantasy in Suburban Los Angeles, Berkeley: University of California Pres, 2004 Axelrod, Jeremiah B. -

State of Immigrants in LA County

State of Immigrants, 1 Los Angeles County State of Immigrants in LA County January 2020 USC Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration and release of this report. Finally, thank you to CCF, State of Immigrants, 2 (CSII) would like to thank everyone involved in the James Irvine Foundation, Bank of America, and Los Angeles County producing the first annual State of Immigrants in Jonathan Woetzel for their support which made L.A. County (SOILA) report. The goal was to create a SOILA possible. resource for community-based organizations, local governments, and businesses in their immigrant We would also like to extend deep appreciations integration efforts. To that end, we sought the to the members of the CCF Council on Immigrant wisdom of a range of partners that have made this Integration for commissioning this report and for report what it is. their feedback and suggestions along the way. A special thank you to all organizations interviewed The work here—including data, charts, tables, for case studies that donated their time and Acknowledgments writing, and analysis—was prepared by Dalia expertise to further bolster our analysis. Gonzalez, Sabrina Kim, Cynthia Moreno, and Edward-Michael Muña at CSII. Graduate research assistants Thai Le, Sarah Balcha, Carlos Ibarra, and Blanca Ramirez heavily contributed to charts, writing, and analysis. Thank you to Manuel Pastor and Rhonda Ortiz at CSII, as well as Efrain Escobedo and Rosie Arroyo from the California Community Foundation (CCF) for their direction, feedback, and support that fundamentally shaped this report. Sincere appreciations to Justin Scoggins (CSII) for his thoughtful and thorough data checks. -

Ers Port Y 2016

LAFLA’s New Headquarters Thank You for Your Support Special Thanks to: Brad Brian Glenn Pomerantz Jim Hornstein Breaking Ground January 2016 CONGRATULATIONS TO TONIGHT’S HONOREES LAFLA Staff and Board Your dedication, passion and commitment THE HON. ZEV YAROSLAVSKY in the fight for equal justice is unparalleled THE HON. HARRY PREGERSON ORRICK, HERRINGTON & SUTCLIFFE Congratulations to tonight’s honorees Hon. Zev Yaroslavsky We are grateful for your partnership and dedication Hon. Harry Pregerson to our mission to provide equal access to justice & Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP Martin T. Tachiki Marc Feinstein You’ve made Los Angeles President Felix Garcia a better place for all of us! Debra L. Fischer Tracy D. Hensley Vice President James E. Hornstein James M. Burgess Gila Jones Secretary Allen L. Lanstra Michael Maddigan Clementina Lopez Silvia Argueta Treasurer Neil B. Martin Executive Director Karen J. Adelseck Louise MBella Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles Client Chair James M. McAdams Wesley Walker Adam S. Paris Client Vice Chair R. Alexander Pilmer “Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts Paul B. Salvaty Robert L. Adler to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against Kareen Sandoval Chris M. Amantea injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope.” Kahn A. Scolnick Terry B. Bates – Robert F. Kennedy Marc M. Seltzer Hal Brody Ramesh Swamy Elliot Brown Ronald B. Turovsky Chella Coleman Rita L. Tuzon Sean A. Commons Patricia Vining Sean Eskovitz Seventeenth Annual Access to Justice Dinner Paying Tribute to Access to Justice Lifetime Achievement Award The Hon. Zev Yaroslavsky Maynard Toll Award for Distinguished Public Service The Hon. -

Understanding Artworlds. INSTITUTION Getty Center for Education in the Arts, Los Angeles, CA

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 445 980 SO 031 915 AUTHOR Erickson, Mary; Clover, Faith TITLE Understanding Artworlds. INSTITUTION Getty Center for Education in the Arts, Los Angeles, CA. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 108p. AVAILABLE FROM Getty Center for Education in the Arts, 1875 Century Park East, Suite 2300, Los Angeles, CA 90067-2561; Web site: http://www.artsednet.getty.edu/ArtsEdNet/Resources. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Art Activities; *Art Education; *Art Expression; *Cultural Context; Inquiry; Interdisciplinary Approach; Secondary Education; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *California (Los Angeles); Conceptual Frameworks; Web Sites ABSTRACT This curriculum unit consists of four lessons that are designed to broaden students' understanding of art and culture; each lesson can stand alone or be used in conjunction with the others. The introduction offers a conceptual framework of the Artworlds unit, which takes an inquiry-based approach. The unit's first lesson, "Worlds within Worlds," is an interdisciplinary art and social science lesson, an introduction to the concept of culture--an understanding of culture is necessary before students can understand artworlds, the key concept of this curriculum resource. The unit's second lesson, "Places in the LA Artworld," the key lesson in this unit, introduces and illustrates the defining characteristics of an artworld. The lesson has students make an artworld bulletin board. The unit's third lesson, "Cruising the LA Artworld," asks students to apply their understanding of the defining characteristics of artworlds from the "Places in the LA Artworld" lesson to their analysis of art-related Web sites on LA Culture Net and beyond. -

Frank Gehry Biography

G A G O S I A N Frank Gehry Biography Born in 1929 in Toronto, Canada. Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA. Education: 1954 B.A., University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA. 1956 M.A., Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Select Solo Exhibitions: 2021 Spinning Tales. Gagosian, Beverly Hills, CA. 2016 Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Rome, Italy. Building in Paris. Espace Louis Vuitton Venezia, Venice, Italy. 2015 Architect Frank Gehry: “I Have an Idea.” 21_21 Design Sight, Tokyo, Japan. 2015 Frank Gehry. LACMA, Los Angeles, CA. 2014 Frank Gehry. Centre Pompidou, Paris, France. Voyage of Creation. Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, France. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Athens, Greece. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong, China. 2013 Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Davies Street, London, England. Frank Gehry At Work. Leslie Feely Fine Art. New York, NY. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Paris Project Space, Paris, France. Frank Gehry at Gemini: New Sculpture & Prints, with a Survey of Past Projects. Gemini G.E.L. at Joni Moisant Weyl, New York, NY. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA. 2011 Frank Gehry: Outside The Box. Artistree, Hong Kong, China. 2010 Frank O. Gehry since 1997. Vitra Design Museum, Rhein, Germany. Frank Gehry: Eleven New Prints. Gemini G.E.L. at Joni Moisant Weyl, New York, NY. 2008 Frank Gehry: Process Models and Drawings. Leslie Feely Fine Art, New York, NY. 2006 Frank Gehry: Art + Architecture. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada. 2003 Frank Gehry, Architect: Designs for Museums. Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, MN. Traveled to Corcoran Art Gallery, Washington, D.C. 2001 Frank Gehry, Architect. -

Thegetty INSIDE This Issue

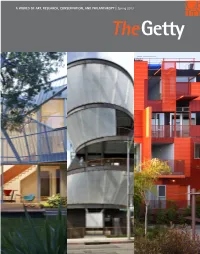

A WORLD OF ART, RESEARCH, CONSERVATION, AND PHILANTHROPY | Spring 2013 TheGetty INSIDE this issue The J. Paul Getty Trust is a cultural Table of CONTENTS and philanthropic institution dedicated to critical thinking in the presentation, conservation, and interpretation of the world’s artistic President’s Message 7 legacy. Through the collective and individual work of its constituent Pacific Standard Time Presents: 8 Programs—Getty Conservation Modern Architecture in L.A. Institute, Getty Foundation, J. Paul Getty Museum, and Getty Research Institute—it pursues its mission in Los Minding the Gap: The Role of Contemporary 11 Angeles and throughout the world, Architecture in the Historic Environment serving both the general interested public and a wide range of In Focus: Ed Ruscha 14 professional communities with the conviction that a greater and more Overdrive: L.A. Constructs the Future 16 profound sensitivity to and knowledge of the visual arts and their many histories is crucial to the promotion Sponsor Spotlight 18 of a vital and civil society. Behind the Scenes: Grantmaking 20 at the Getty New Acquisitions 25 FOR ADVERTISING INFORMATION From The Iris 26 Margaret Malone Cultural Media Inc 1001 W. Van Buren Street New from Getty Publications 28 Chicago, IL, 60607 [email protected] From the Vault 31 (312) 593-3355 On the cover, from left to right: Palms House (detail), Venice, California, 2011, Daly Genik Architects. Photograph Jason Schmidt. © Jason Schmidt; Samitaur Tower (detail), Culver City, California, 2008–10, Eric Owen Moss. Photo: Tom Bonner. © 2011 Tom Bonner; Formosa 1140 (detail), West Hollywood, California, Lorcan O’Herlihy, 2008, © 2009 Lawrence Anderson/Esto © 2013 Published by the J.